Reporter: Andy, a Canadian government spokesman said that your art could not be described as original sculpture. Would you agree with that?

Andy Warhol: Uh, Yes.

Reporter: Why do you agree?

Andy Warhol: Well, because it’s not original.

Reporter: You have just then copied a common item.

Andy Warhol: Yes.

Reporter: Well, why have you bothered to do that? Why not create something new?

Andy Warhol: Uh… because it’s easier to do.

Reporter: Well, isn’t this sort of a joke then that you’re playing on the public?

Andy Warhol: Uh, no. It just gives me something to do.

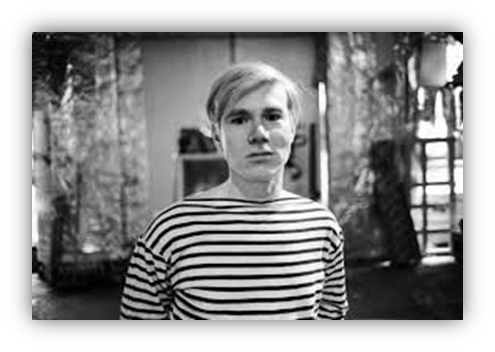

It was in the early 1960s that Andy Warhol finally came into his own.

His work polarized the art world at the time, and was covered in the press as some inscrutable mystery.

His reputation as a creative powerhouse has since been solidified among the cultural elite. Yet he remains a controversial figure among laypeople even now.

Was he a genius? A freak show? A con man?

It depends on who you ask.

One of the major charges against Andy Warhol is that he contaminated the art world with shameless, brazen commercialism.

Another attack centers on the notion that he simply copied existing designs. First by painting replicas of known brands. And then later by using silkscreen prints of found photographs. And sometimes even having other people do the printing for him.

What was he creating, beyond publicity stunts?

The third charge is that his pieces had no discernible meaning, they were just empty spectacle. This was a sentiment that Andy himself would often agree with!

However you may feel about his art, we can all agree that Warhol’s approach was radical and provocative for the time. It’s safe to say that our culture was transformed by his art and the movements he helped create.

But I tend to think of him as a herald more than anything else. Someone who announced a new age.

The times indeed had changed. Warhol’s art spoke truths about our culture that no one wanted to admit. For a while at least. Eventually, everyone caught up.

Graven Images:

It’s worth taking stock of how much art had changed over the centuries due to changes in societal culture and technology.

The first time a piece of visual art could be revered as a work of “genius” was the medieval period of Europe.

Before then, even in classical Greece, painters and sculptors were seen as lowly artisans: sometimes very skilled in their depictions, but never divinely inspired.

But the medieval painters of holy icons: they could channel the power of the Lord with their depictions of the saints, or of the biblical scenes. Like the Father who blessed them, these mostly anonymous men were able to create something from nothing, and touch the souls of others.

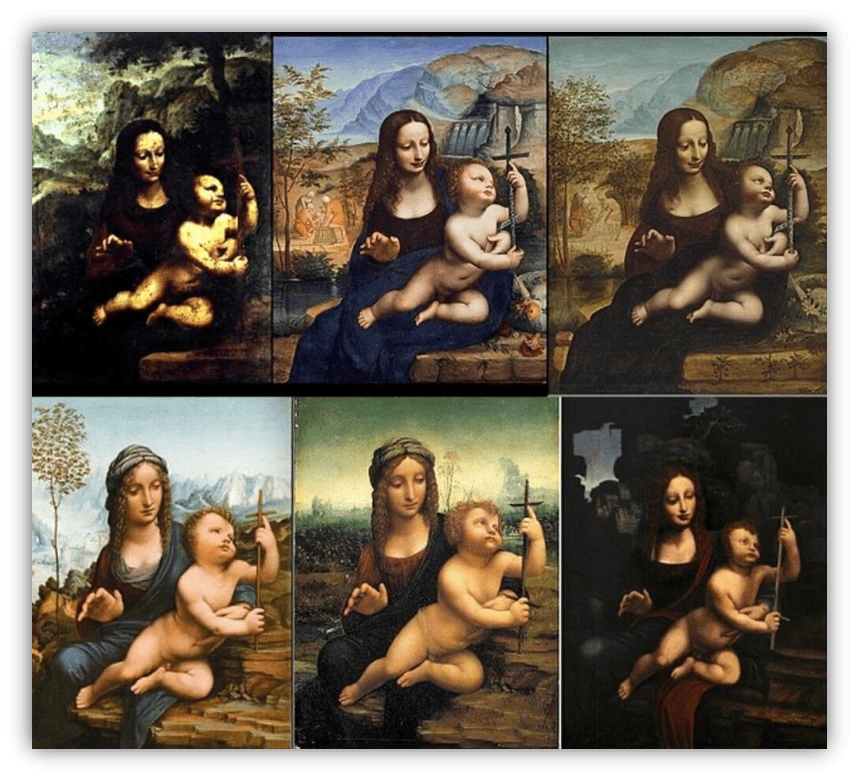

By the Renaissance, individual artists could actually gain fame and recognition for their unrivaled talent and creativity. European painters and sculptors elevated the standards for visual representation to the realistic depictions of the ancient pagan world.

The masterpieces of talents like Michelangelo and Leonardo Da Vinci were not only made for chapel walls and ceilings, but also to decorate the home of wealthy patrons.

The artists also granted their patrons a life beyond death by fixing their image in painted portraits or in stone. Aspiring artists took to copying the works of the masters in order to learn from them—and sometimes merchants sold such forgeries as originals.

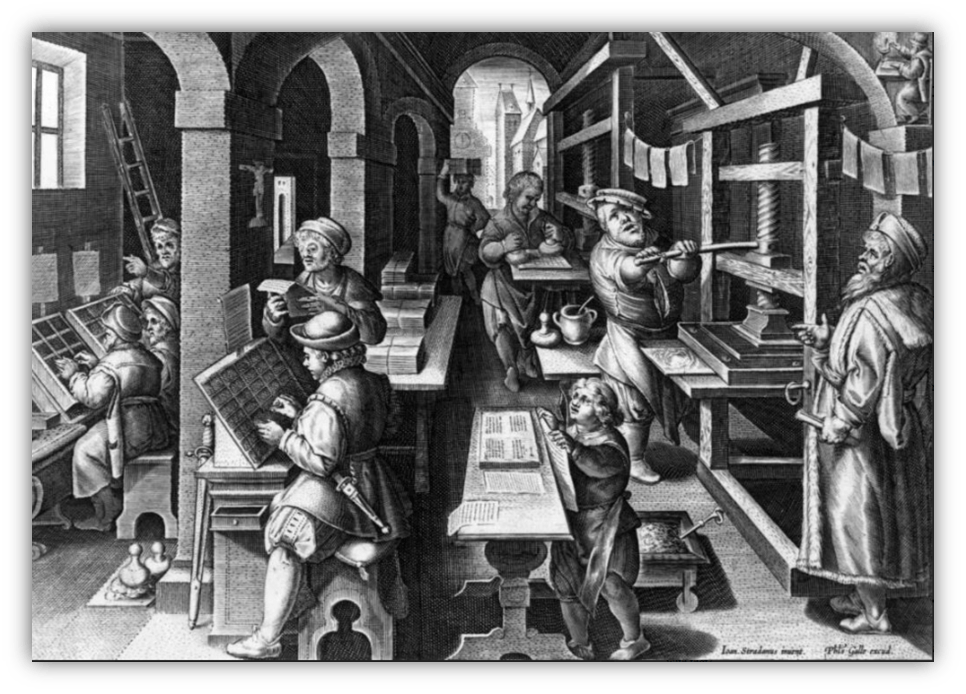

With the Enlightenment came the industrial revolution, the dawn of rapid technological advancement and dramatic societal change.

The printing press and resulting Protestant Reformation being the most important of these. Monarchs established copyright laws in order to contain the flow of information and power, but rogue words and images nevertheless continued to spread.

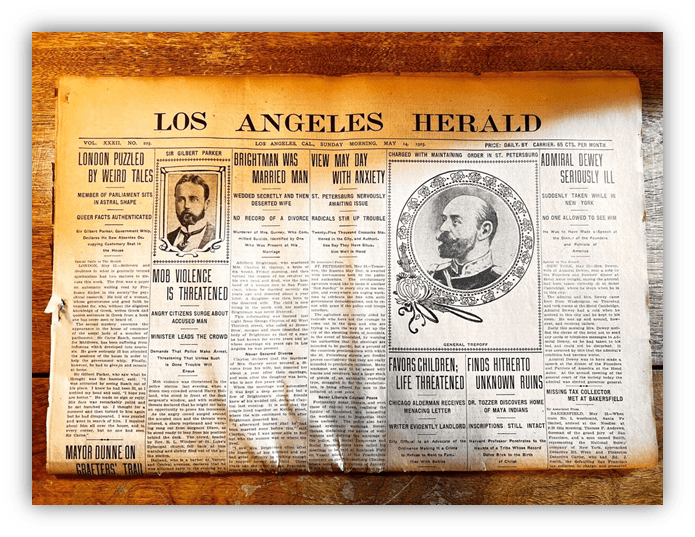

By the beginning of the 20th century, cultural transformations due to industrial production were absolutely everywhere. The printing press enabled the formation of the first newspapers.

These could inform local residents of notable events and social issues, thereby laying claim to a growing public sphere of awareness.

To be published in newspapers was to be made public, and publicity soon became a powerful way to capture the attention of the masses.

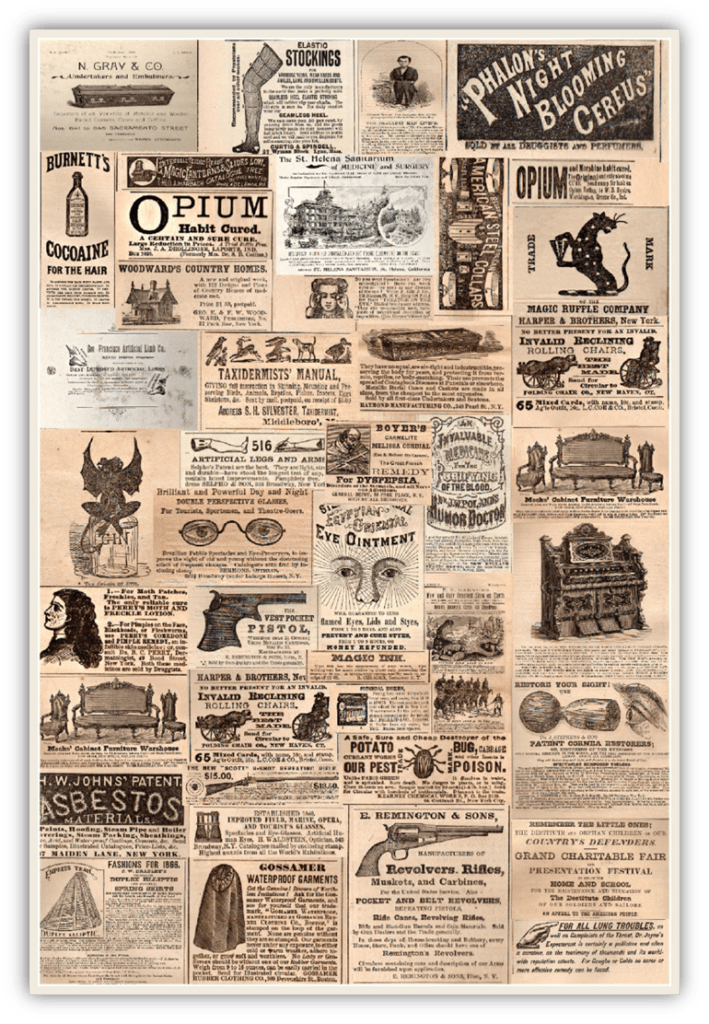

And it wasn’t just current events that were publicized.

Commercial advertisements boomed in the early printing age, encouraging readers and passersby to buy various products. Eventually, the advent of lithographic printing allowed the replication of illustrated drawings, and these were often printed along with typed texts to further attract attention.

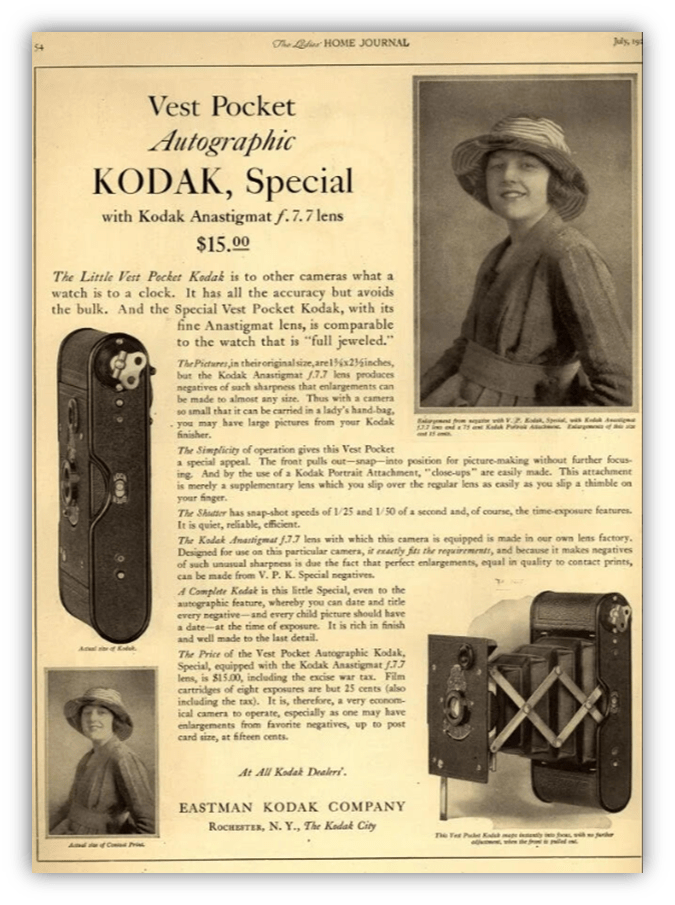

Then, thanks to the invention of the photograph camera, realistic visual representations of the world were suddenly available at the press of a button.

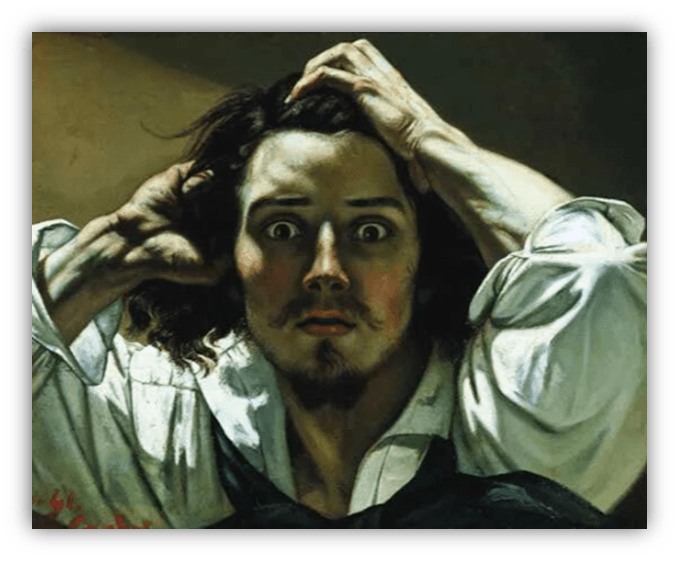

For centuries, European painters had gained fame and fortune by rendering realistic pictures via careful strokes of oil on canvas. Suddenly this treasured method of visual depiction was out of date, and the status of artists as cultural heavyweights received its first major challenge.

Once realistic photos became so easy and effortless to produce, most painters concerned themselves with functions other than accurate representation of the material world. Instead, they focused on making images that were expressive, or mysterious, or conceptually intriguing, or politically potent.

And it was starting from this time that the public appreciation for art began to fracture and wane, as art steadily shifted away from fairly objective considerations of character and setting to increasingly subjective or esoteric ones. Hence the emergence of Impressionism, Abstract art, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism etc, etc.

Ironically, despite their popular dismissal as empty and decadent, modern painters often sought to restore a sense of spiritualism to the visual arts. But their spiritual transcendence always required their audiences to be challenged. And so their audiences diminished over time. Most people sought out simpler, more convenient, and more relatable pleasures.

Going forward, it would not be the weirdo bohemian geniuses who would dominate the new culture. Instead, it was clever business entrepreneurs using new media to capture common desires and turn a profit.

Newspapers, magazines, radio, film, and then television; these were the public squares where most of the action took place.

And the people paid attention to whatever was reported to them, or delivered into their homes. Sometimes a painter or an art premiere would gain publicity from time to time, but it was usually at the behest of media moguls looking for a sensational story, or a chance to sell ad space.

God and Mammon

Despite being known as the father of Pop Art, Warhol wasn’t the first person to blend artistic and commercial motives.

George Gershwin and Berthold Brecht wrote operas based on popular music styles. Jazz bands created edgy, intellectual entertainment. Early art cinema aimed to please and also challenge the masses. And let’s not forget Toulouse-Lautrec’s stylish commercial lithographs from the late 19th century.

But in the elite circles, there remained a great disdain for commercial art. Most visual artists avoided kitsch or commercial content in their pieces, or they approached it from a critical standpoint. To them the difference was like night and day. Either art was serious, or it was not.

Unlike most artists of his time, Andy Warhol was not born into wealth or privilege.

He was the son of immigrant parents, and grew up in a poor Eastern European section of Pittsburgh.

Thankfully, his family had a radio and television. As a child, Andy would soak up American culture as most people around the country did: through the news, through television commercials or radio jingles, through tabloids, through fashion magazines, through print ads, and through popular films.

Yet despite his humble background and working-class family, Andy was always unique, set apart from the rest of his community. And he dreamed of finding success in America’s biggest city. In 1949, after graduating college with a degree in Fine Arts, he moved to New York City to follow his dream.

The pieces he made during his early days in New York are unrecognizable to most people today as being his. They were conventional paintings or illustrations, albeit with a strong sense of charm.

Although his first works were not commercial, Warhol was nevertheless ostracized by most of the artistic cliques of the time. Why? Because he worked a day job as a commercial designer. After several years failing to keep up these two conflicting pursuits, Andy eventually decided to merge them together.

His first pop art work was a drawn copy of a panel from a Superman comic. Superman was a figure mostly worshipped by young boys at the time. This cartoon figure, made famous via stories printed on pulp paper and sold for a dime each, was given pride of place as a fine art exhibit. And as such, the piece served as the entry point of a new kind of cultural iconography.

The saints of Andy’s new religious canon included brand names like Brillo and Coca Cola. They included Hollywood celebrities, living or dead. They included tabloid stories and comic book heroes.

They included every flavor of Campbell’s soup can.

Warhol’s central accomplishment as an artist was really quite simple: he acknowledged the real gods of modern culture.

With his pieces, the notion of sacred high art was effectively killed for good and all. How did he do it? Not by trashing the institutions, as the Dadaists tried to do. He did it instead by venerating all of the aspects of modern commercial culture that elite artists reacted against.

Just like the portraits and still life paintings of the 1600s, he showed our culture largely as it was. Given that elite art circles were driven by bohemian ideals for almost two centuries before pop art emerged, this gazing into the mirror came as quite a shock. Many established artists recoiled in horror at the unseemly reflection.

Quid Est Veritas?

What about the painstaking efforts needed to cultivate detail and precision in a painting? It could be said that they were relics of a bygone era, before industrial technology changed everything.

Warhol was in fact a gifted illustrator, but his most powerful contributions were via his role as a curator.

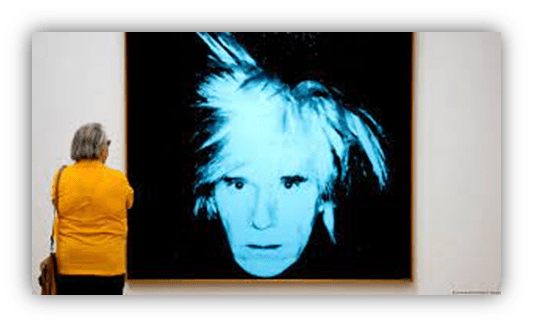

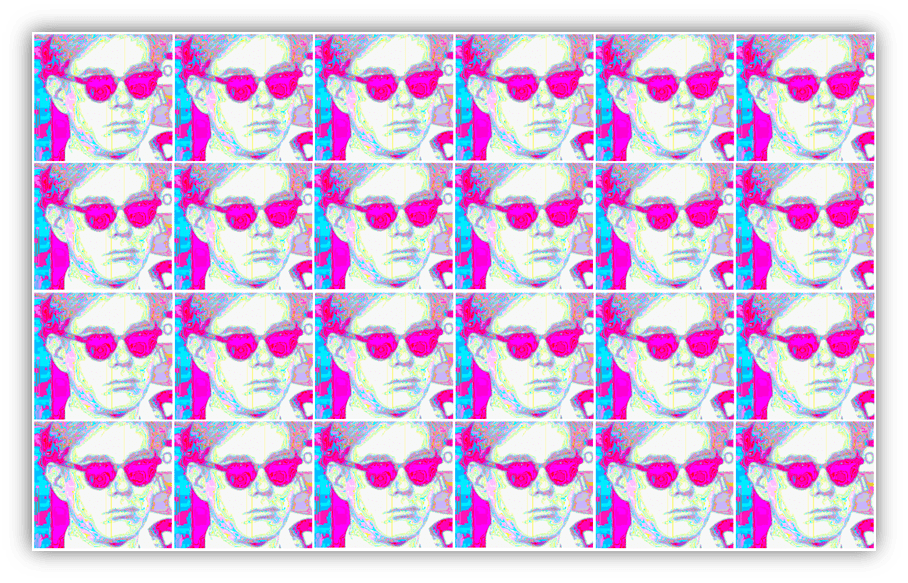

He soon employed the techniques of the commercial industry to his work as well. First by using silkscreen prints of photographed images to create endless repeats of pop culture prints. And then, by assembling a team of workers to help him do the grunt work.

Over the course of the 1960s and 70s, the coterie within his Factory studio gave birth to countless works of new and exciting art from all possible media. And only a portion of them came from Andy himself.

Well, what about the meaning of his work? Was it really just empty spectacle? Or was there truth or beauty to be found? There is certainly room for subtlety and sophistication in Warhol’s pieces.

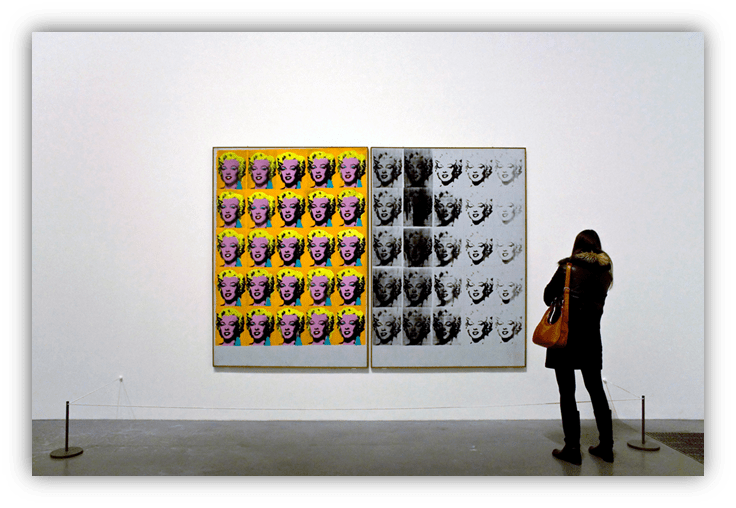

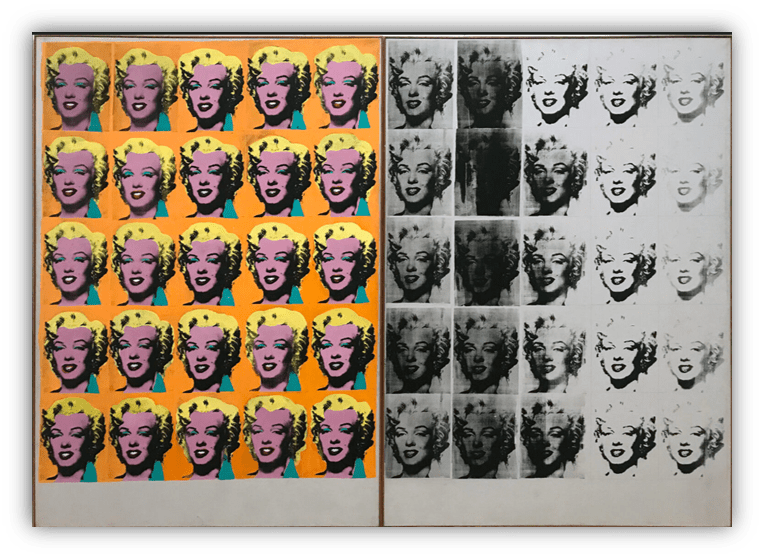

Take for instance, his Marilyn Monroe Diptych from 1962:

These are repeated silkscreen prints of one classic photo image, with two different choices of ink color and some dramatically varying print quality. The compulsive duplication of Marilyn’s image for an art exhibit surely serves as a testament to Warhol’s reverence for the recently deceased celebrity.

Yet the imperfectly printed repetitions of her face also speak to the frailty of her existence. And as such, it whispers a hint of our own impending end.

But really, there is no one valid interpretation to Warhol’s pieces. Keep in mind that being open to interpretation was the defining feature of Western fine art following WWII. Warhol was no different in this respect from painters like Jackson Pollock or Robert Rauschenberg. Or composers like John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen.

Of course, a key difference from those precursors is that Warhol’s pieces can easily hit our pleasure centers.

Even if you don’t get a deeper meaning from them, they’re a delight to see.

And so, if you’re not motivated to engage in careful contemplation, then his pieces really can be nothing but empty spectacle. And let’s be honest, it’s often hard to find the time or energy to challenge ourselves these days. Our work days are long, life is complicated, and we all could use some time to kick back and relax.

Simple pleasures and empty spectacles will almost always win out in today’s market. And for his part, Andy Warhol seemed just fine with that.

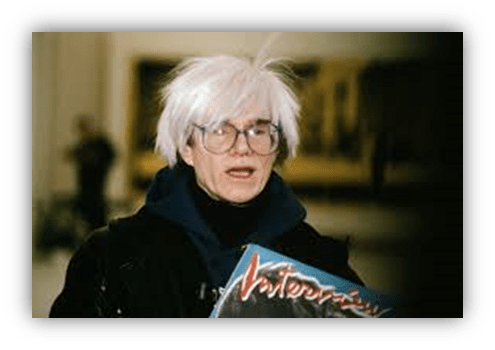

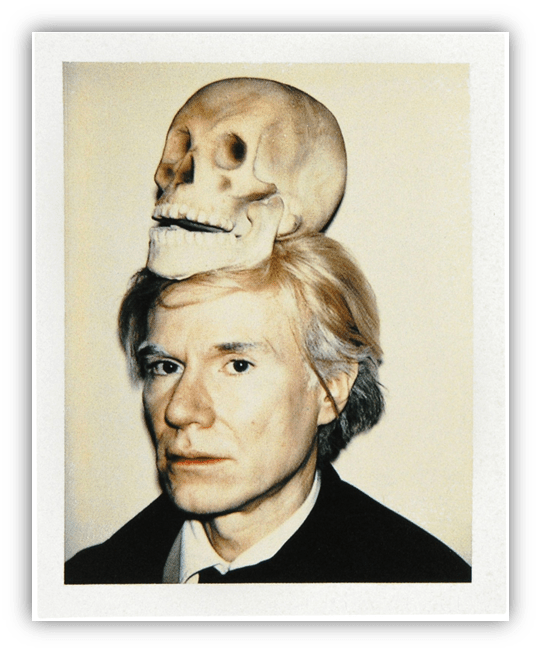

For all his moments of self-deprecation or his starry-eyed fixation with the world around him, Warhol was a thoroughly savvy figure, gaining widespread popularity and influence mostly by means of passive reflection.

Here was an artist who actually understood the power of branding and self-promotion, just as he understood the tremendous power of publicity. He accepted the reality that print and television journalists were the modern arbiters of public consciousness.

And so he happily played into their stereotypes of him as a fad, a con man, and a mysterious blank slate. All the better to grab national headlines and showcase his works. He always did have an eye for good copy.

It would take a few decades for his innovations to sink in, but Andy Warhol helped to usher in the postmodern era of art.

From here on out, the lines between high art and low art were blurred beyond comprehension. Culture was sometimes incisive, and always entertaining. Meaning and value seemed a whole lot more subjective. Ultimate truth seemed elusive; perhaps ultimately unknowable.

Whatever his works may mean and however they may be valued, Warhol’s ascendency to modern art legend undeniably marked the start of when the art world first learned to stop worrying and love…

The Brillo pad?

The Beatles?…

… What was the question?

[Note: This post was made from 40% recycled blog materials. Any resemblance to actual copyrighted works is purely coincidental and/or a unique recontextualization and/or a loving reference. Tee hee!]

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Soundtrack for today’s post:

https://youtu.be/KGZWb1SIiR4?si=FcSD4cybNV2i84Oy

Probably my personal favorite of Warhol’s projects was his early fostering of the Velvet Underground.

Letting the band do whatever they wished was his greatest gift to them, and us.

Not to mention giving Lou Reed plenty of material to write about via the scene he created.

As for my own personal favorite, it’s hard to compete with the Brillo boxes. Meaning be damned, they are a delight to look at.

This was played for my sister’s first dance at her wedding. Love it.

A much better choice than “Heroin!”

Indeed.

Their first choice was actually “There is a Light That Never Goes Out” by The Smiths, but they switched it at the last minute. I ended up playing that one on the piano during the cocktail hour.

This is as good an explanation of Warhol as any I’ve ever read. He sure knew how to bend media to his will.

Perhaps the epitome of soft power. Like a velvet glove cast in…Velveeta?

I’m pretty sure they broke up but….

Or at least hardened.

Oh boy…

Warhol’s art seems very easy to appreciate. His fascination with commercial, mass produced art just comes naturally, I think. I remember being a kid and over time trying to collect the wrapper of every flavor of life savers. Putting them together in some sort of display not unlike Warhol’s collection of Campbell’s soup flavors display is exactly what I would have wanted to do.

His films are another matter.

Although maybe I shouldn’t judge until I get through at least four hours of the Empire State Building.

Is Warhol responsible for the development of the annoying modern art sceptic? Who see the apparent simplicity of a Cambell’s Soup can and dismiss it with a curmudgeonly “I could have done that.”

Irrespective of that, I like the simplicity and the lack of pretension in that encounter with the journalist. Why try and dress it up? It is what it is and if you want to assign your own value and interpretation that’s none of his concern.

What seem to be the classic Warhol pieces; Monroe, Campbell’s Soup, Elvis and even the films and Velvet Underground date from the 60s. I’m not familiar enough with his career to know what he did with the rest of his life. Did he carry on in the same vein or move onto new forms and styles? Are there any later works that are particularly worth looking up?

He is indeed often touted as one of the major examples of the “art is a joke” criticisms. But my parents said “I could have done that” about Jackson Pollock as well. And even Edvard Munch’s works from the late 20th century!

If it’s not showing off the technical feats of skilled draftsmanship, it’s at risk of being dismissed and demeaned. Warhol was maybe not the pioneer so much as the culmination of it.

I’m not too familiar with his late life work beyond his stuff with Basquiat. If you haven’t seen the movies he produced with Paul Morrissey–they are phenomenal. Flesh and Trash were extremely edgy for their day. And Dracula is just hilarious.

Whoah…I just learned that Paul Morrissey co-wrote and directed The Hound of the Baskervilles.

*mind blown*

Andy: Everybody will be famous for fifteen minutes.

(mic drop)

Andy: What? Now you want me to paint something? I’m Nostradamus, b*tch. I don’t have to paint s***. My legacy is secure.

Lou: Duck, Andy! Duck!

(gun shot)

(thud)

Lou: Nico! Behind the Silver Clouds of Dissent installation. It’s the SCUM Manifesto chick.

Nico: Oh, the ennui, the ennui.

(groans)

Lou: Andy, are you okay?

Andy: (unintelligible mumbling)

Lou: What?

Andy: Come closer, Lou. Closer. Closer.

Lou: You lost a lot of blood, Andy. Try not to talk, you-

Andy: One day, Lou, you’re going to write a song called “Perfect Day”. It’s going to be a great song, your best. All these important artists are going to cover it. You’re going to be flattered. People who can actually carry a tune will sing your words, your beautiful words, Lou. But it’s going to be a pin-up idol, some pretty boy with a moussed-up mullet who will top them all. Tell him…it made you cry. It’ll mean something to him. Tell him!

Andy: Okay, Andy. I’ll tell him. Hang in there, Drella.

Nico: Is he dead yet?

(distant sirens)

End scene.

Lili Taylor didn’t get enough leading roles. She was great in Mary Harron’s I Shot Andy Warhol. Dogfight(inspired pick) made it into the collection. I think I Shot Andy Warhol has a shot.

Great film. Mary Harron is an underrated talent. Apparently she made a film about Dali! I need to see that.

Jared Harris was fantastic as Andy Warhol. Much better than David Bowie in Basquiat. Who was certainly endearing, but mostly was just an airhead version of David Bowie.