As mentioned in a previous post:

European composers took modernism to new levels of methodological rigor and difficulty in the 1940s and 50s.

This rather academic approach dominated classical circles for some time. American university music departments in the 1960s were still enamored with Stockhausen and other European experimental composers.

Yet according to the young composer Steve Reich, his university colleagues were out of touch. They didn’t represent any new American music that was worth a damn:

“Stockhausen, Berio and Boulez were portraying in very honest terms what it was like to pick up the pieces of a bombed-out continent after World War II.

But for some American in 1948 or 1958 or 1968…In the real context of tailfins, Chuck Berry and “millions of burgers sold”…to pretend that instead we’re really going to have the dark brown angst of Vienna is a lie, a musical lie.

And I think these people are musical liars, and their work isn’t worth….[snaps fingers]…that!”

Steve Reich -1987

A harsh dismissal to be sure. But it’s one that nicely sums up what was bubbling up in the nation’s most adventurous music communities.

Even so, to call it the next step of modernism is to oversimplify. What emerged in the 1960s wasn’t simply the next new thing. As we will see, older ideas did indeed drift away from the new. But as they drifted apart, sometimes they harmonized rather than clashed. Sometimes the conflict gave way to an infectious, hypnotic rhythm.

All was in flux.

One of the major new signatures was a shift in how composers thought about the notion of time.

Morton Feldman was perhaps the first major influence in this respect.

Feldman had been friends with John Cage since 1950, and had helped Cage develop his technique for chance compositions.

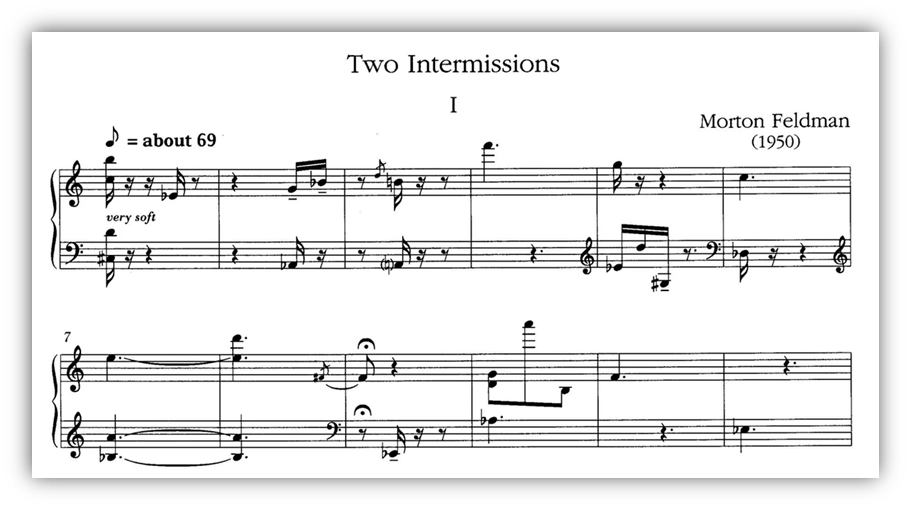

Feldman’s own compositions were slow and spare. Some of them featured sadly sweet melodies, while others showcased more modern tonality.

But nearly all of them were dominated by silence and space between the notes, as if appealing to higher powers beyond the buzz and churn of modern life, forces outside of time.

He once said: “I like to live well, to eat well. I like to live fast, because in my art I feel myself dying very, very SLOWLY.”

Feldman was a huge fan of the painter Mark Rothko, even composing a commemoration piece upon the artist’s death. Rothko’s giant blocks of color imposed upon viewers eternal states of the human condition. Feldman sought to achieve similar results in his work. Except instead of using vast canvass space to conjure his sense of the grand and infinite, he used vast measures of musical time.

Feldman played with time in other ways as well.

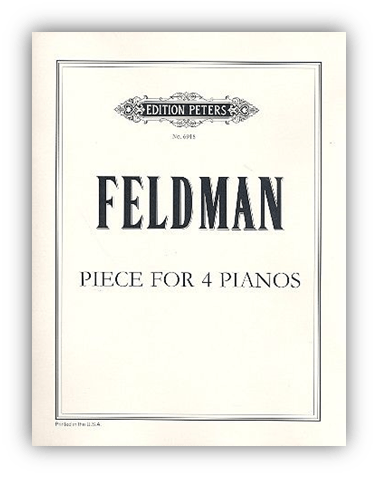

In a 1957 work co-written with John Cage, Feldman had four pianists play the same score, but gave them all the freedom in interpreting the timing of the notes. The result is a haunting melody with components that fall in and out of phase with one another.

Like entropy put to music.

This piece was the seed of an idea that younger composers would explore more thoroughly in the following decade.

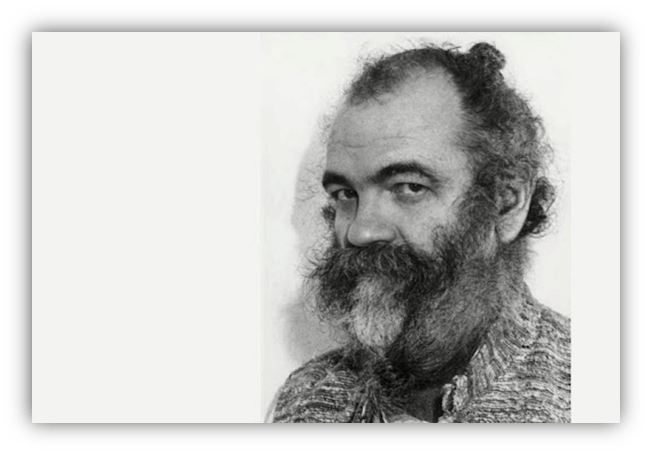

Another innovator, perhaps the most important to the new movement, was La Monte Young from California.

Young almost had a promising career as a jazz musician. At Los Angeles City College, he tried out for second saxophone chair in the school dance band, and beat out future legend Eric Dolphy for the position.

Young and Dolphy became friends, and he played gigs with other up and coming jazz musicians, including Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry. But his future ultimately lay in modern composition.

At the University of California, Berkeley, Young was trained in the ways of 12-tone serialism, and he soon fell in love with the sound production experiments of Stockhausen. But like Morton Feldman, he didn’t want to jump from one musical element to the next in his compositions.

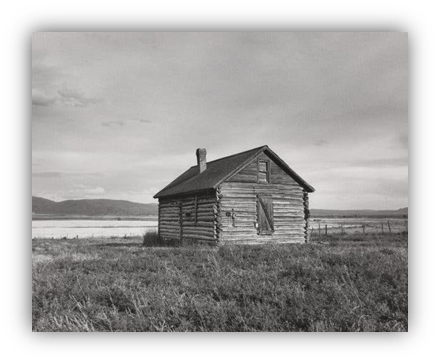

La Monte Young had been born and raised in a log cabin in rural Idaho. In his childhood years, he tuned his ear to the ambient noises of the world around him.

Crickets and katydids. Wind whistling. The hum of electrical poles. The music of his environment was slow, steady, and seemingly endless.

Young’s breakthrough as a composer was to meld the modern ideas of Webern and Stockhausen to classical Indian and Japanese music, both traditions built around repetitive drones. Rather than flit from note to note, Young developed a music that would be as steady and patient as the sounds of his childhood.

His first major composition was the 1958 Trio for Strings.

Using cello, violin, and viola, the piece consisted of long, sustained notes playing on and on, each movement consisting of one static chord. The result was a transcendent drone, featuring what Young would call his “Dream Chord,” one inspired by the electrical hum of telephone poles.

Like most new composers, John Cage was an important influence on Young. Cage was happy to trade ideas with European modernists, yet he was eager to free music from the shackles of European tradition. His adventurous and playful approach to hearing and performing music lit the creative fires of the younger artists, including La Monte Young.

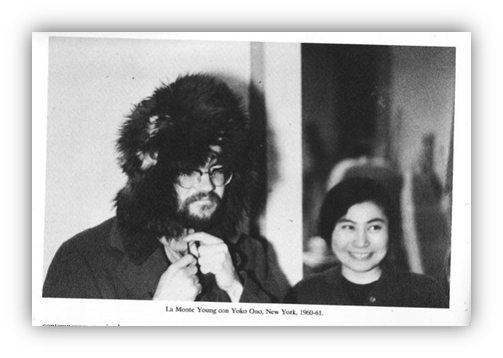

Young first learned about Cage while studying at Berkeley, but he came to fully embrace his conceptual aesthetic once he moved to New York City in 1960.

There he became friends with the likes of George Maciunas and Yoko Ono, who were starting a Neo-Dada art movement inspired by talks John Cage had given at The New School in Manhattan.

This movement emphasized the process of creation rather than on providing new items for wealthy collectors. It was later dubbed “Fluxus,” highlighting the movement’s focus on processes, journeys, and never ending transition.

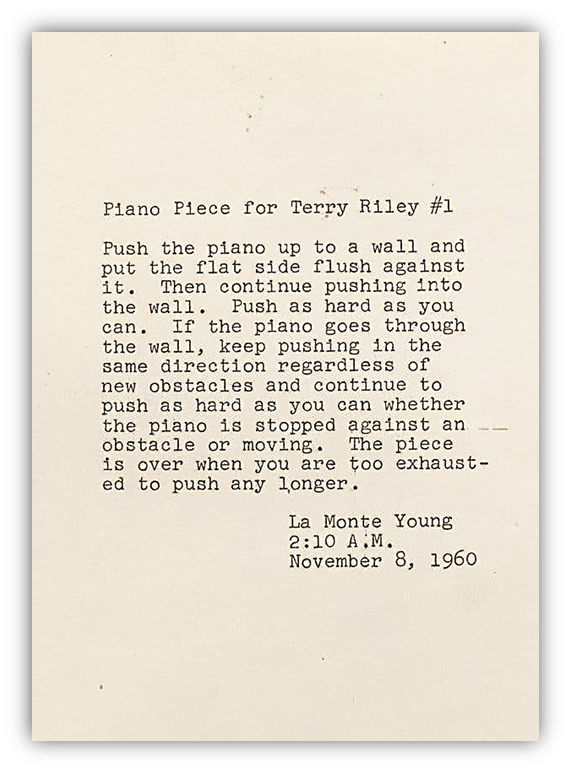

During this time, Young wrote some conceptual compositions that vastly opened up the notion of music performance. Such as: “Turn a butterfly loose in the performance area.” And “Draw a straight line and follow it.”

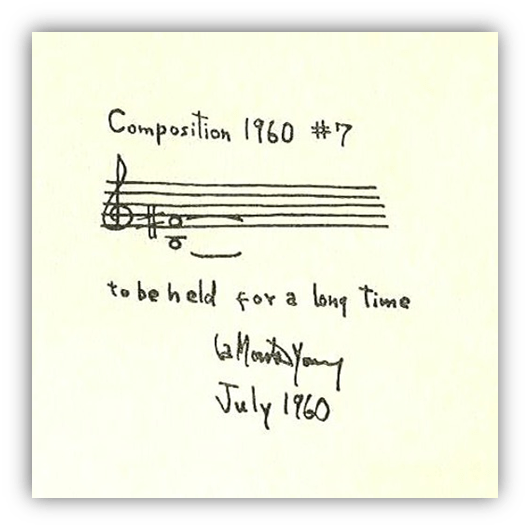

But he also composed what is perhaps his perfect statement of musical minimalism:

His 1960 “Composition #7.”

The score is just two notes: a B3 and an F#4. The instructions say to hold the notes “for a long time.”

Here is a performance of the piece arranged for tapes. Simple. Elegant. Heavenly.

Back when he was studying at Berkeley, La Monte Young found a kindred spirit in Terry Riley.

Riley had a background in jazz piano, and was just starting to experiment with tape compositions.

Young got his friend into the explosive improvisations of John Coltrane, as well as the conceptual compositions of John Cage.

The two would collaborate one and off in the years to come, sharing ideas and branching out in equal measure.

Riley’s earliest tape experiments feature Chet Baker playing saxophone, albeit with prominent delay effects turning his cool jazz style into repetitive hypnosis. The piece got Riley to think about elements shifting in and out of phase, as with Morton Feldman’s earlier piano piece.

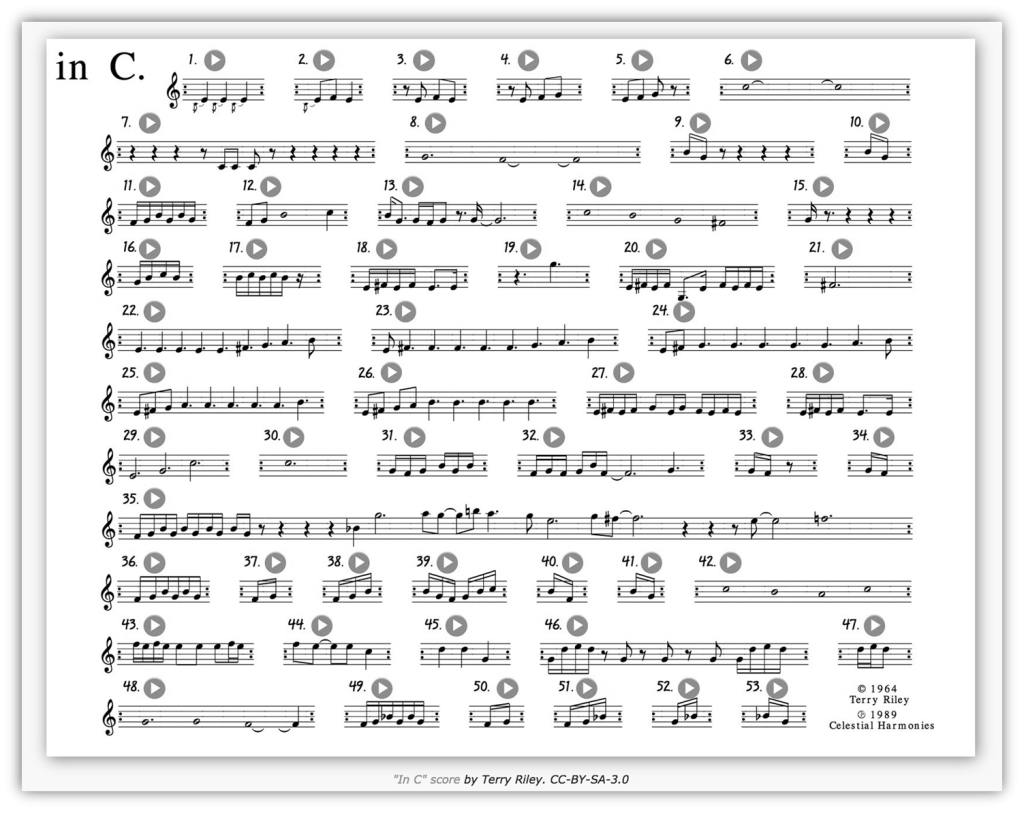

He built upon this idea in his 1964 piece In C, in which a series of brief musical phrases is played by a large group of musicians.

Each musician may repeat a given phrase for as long as they wish before moving on, providing a large element of chance to disrupt the initial synchrony.

Throughout it all, one musician steadily pounds away in the key of C, providing a rhythmic pulse to the collective din.

Unlike Cage and the European modernists, Riley and Young weren’t out to alienate their listeners, or even really challenge them. They were pursuing ideas and sounds that appealed to them. As such, they often worked with conventional music scales, sometimes offering sweet chords or inviting melodies. Still, these works require an open mind and plenty of patience. Riley’s In C piece is equal parts hypnotic bliss and cacophonous disorder.

The idea for the steady rhythm in the piece came from Riley’s friend, Steve Reich.

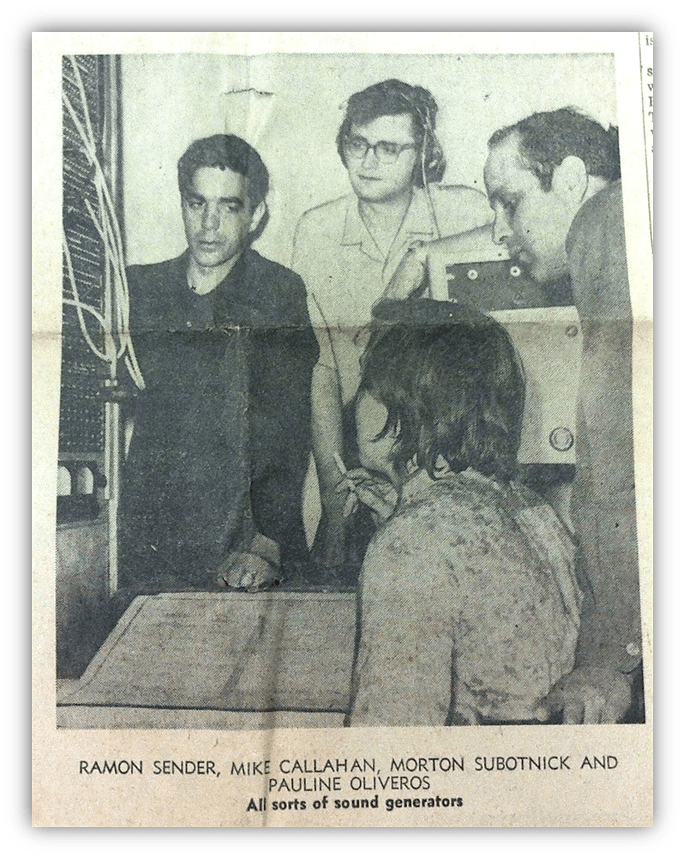

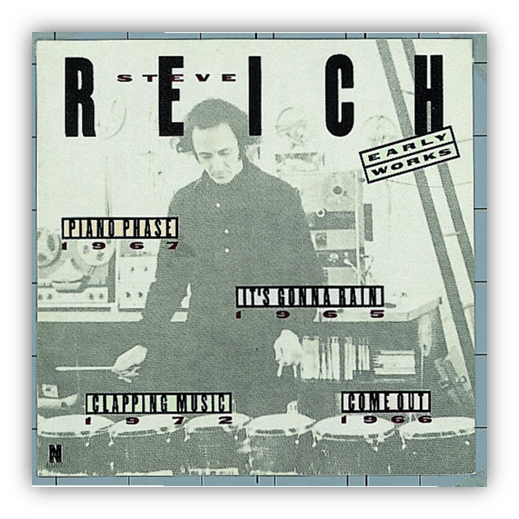

Reich was from New York, but he worked with Riley for a time at the San Francisco Tape Music Center, where he honed his own sound manipulation techniques.

Like Young, Reich’s ear for music had been shaped by the ambient sounds of his childhood. But in Reich’s case, it was the steady clang of train cars hitting tracks, of windshield wipers dancing back and forth. Later, he became inspired by the tribal-inspired drums of Moondog, a composer who played the streets of Manhattan. And by the minimal modal jazz vamps of Miles Davis and John Coltrane.

Like Riley (and like Feldman in 1957), Reich was fascinated by temporal offsets among identical components, yet he sought a more systematic exploration of phase delays that steadily grew as a piece went on, creating new sounds and rhythms over time.

In 1966, Reich created his first piece in this vein: “It’s Gonna Rain.”

It was a simple tape construction: two tape reels playing the same vocal sample over and over in a loop. The sample came from a Pentecostal preacher recorded from the streets of San Francisco. The two tapes start out perfectly synchronized, but over time they drift further and further out of phase with one another. Slowly, over time, dissonance emerges, as do new rhythms, as the two sample sources weave in and out of sync. The resulting piece is often disorienting, and sometimes terrifying.

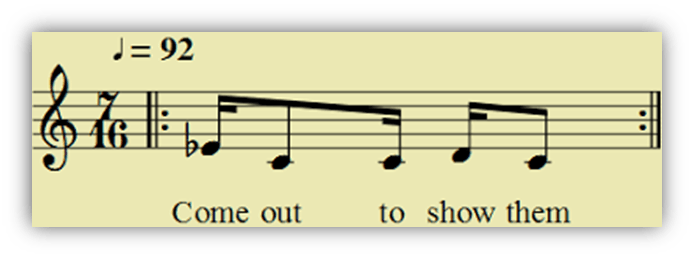

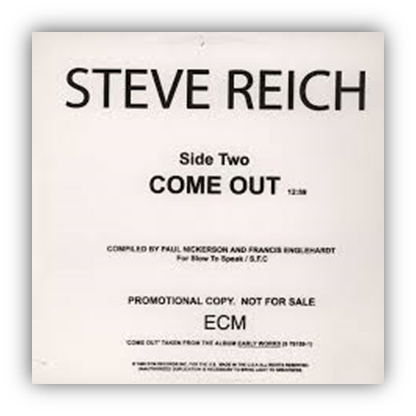

If you want to try to listen to one of Reich’s tape pieces, I recommend his follow-up work “Come Out.” This takes a short sample of a young black man who was interviewed after a 1964 riot in Harlem.

In the clip, the young man describes how he had to puncture his own wound in order to get medical attention from the police following the riot:

and let some of the bruise blood

come out to show them.”

The phrase “come out to show them” repeats over and over, just as the preacher’s words did in “It’s Gonna Rain.” But unlike the preacher, the young man here is not serving a fiery apocalyptic screed.

Despite the desperate situation he describes, his voice is calm and cool.

As such, when the two tapes start to shift out of phase, the result is far less unsettling than Reich’s first attempt. Sometimes its chaos is unnerving, and yet other times a rhythm jumps out and you want to nod your head. Sometimes you expect a hip hop beat to emerge.*

As with Riley and Young, Reich wasn’t offering the world easy pleasures, but he wasn’t averse to pleasure. He followed his tape experiments with more traditional composed pieces that explored similar phase delays between its players. And these pieces featured repeated arpeggios of rather conventional melody.

The arrangements were stark and tense, and the phase offsets introduced some madness, but at least this new cultural leader was offering some spoonsful of sugar to help his medicine go down.

In New York City, the various strands eventually converged.

Older musicians were swept into the orbit of this new movement, and younger ones joined in as well.

The young Philip Glass had been trying to formulate his own sound when he took a class by Steve Reich. In 1968, Glass composed Two Pages for Steve Reich, the first to feature his now signature use of repeating melodic arpeggios. He would continue to build on this minimalist aesthetic, and would eventually even find commercial success doing so.

Meanwhile, La Monte Young formed a collective dedicated to channeling the sounds of heaven.

This was the Theater of Eternal Music, which focused exclusively on impromptu sessions of long, sustained drones.

Thanks to violinist Tony Conrad and the violist John Cale from Wales joining in, the Theater would eventually embark on loud, distorted, amplified drone music—an important precursor of Cale’s later band, The Velvet Underground.

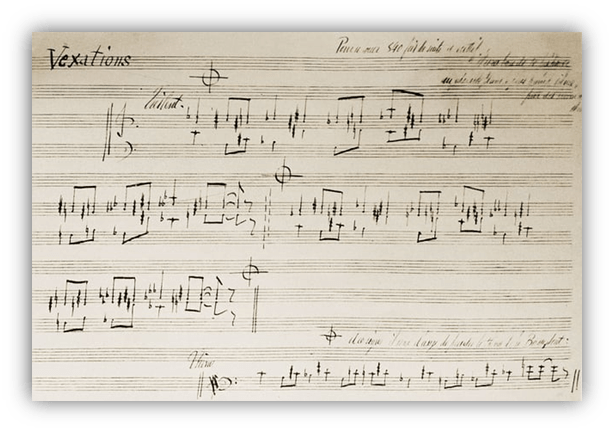

Even Erik Satie joined in on this collective minimalism, at least by way of John Cage. Cage had discovered a piece of Satie’s from around 1894, when he was looking through his notes.

This piece, “Vexations,” featured the curious instructions: “In order to play the motif 840 times in succession, it would be advisable to prepare oneself beforehand, and in the deepest silence, by serious immobilities.”

Satie’s note was probably a joke, probably never even intended to be seen. But Cage was inspired to take it seriously.

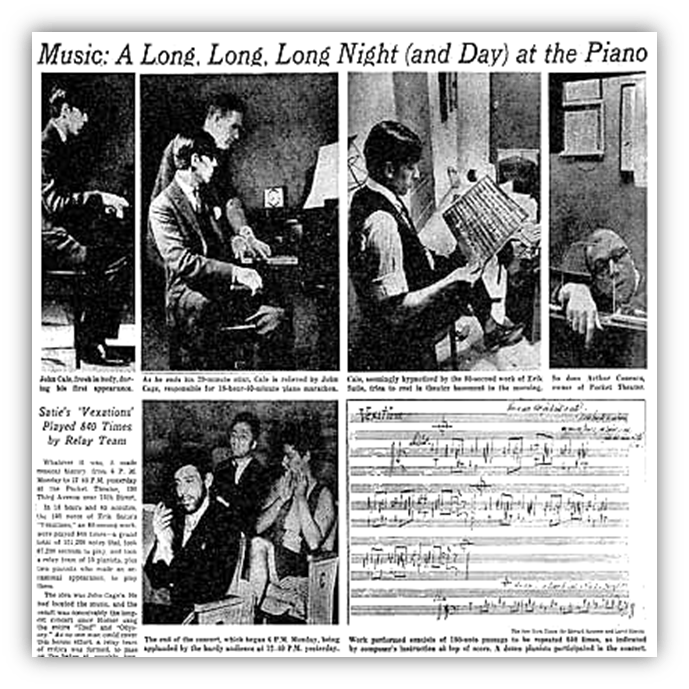

He arranged to have it performed in 1963, where the short piece was repeated over and over, 840 times. The length of the performance required 12 players to work in shifts, including a news reporter who was convinced to join in.

The full performance lasted 18 hours, and only one man stayed for the entire piece. But plenty of people popped in and out of this dedicated communal effort, including Andy Warhol.

Shortly after, Warhol began experimenting in longform video pieces, such as his film centered on his lover sleeping (5 hours) and the Empire State Building (8 hours).

Not to mention, in between pioneering his own textural approach to heavenly sounds, the Romanian modernist Gyorgy Ligeti interacted with Fluxus for a time.

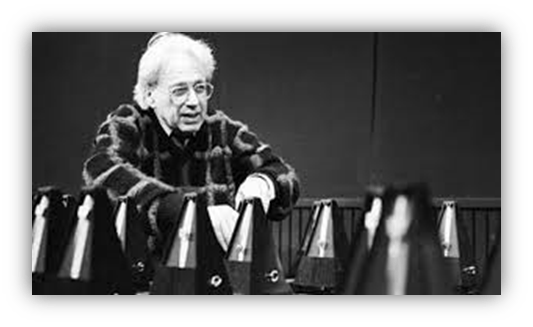

He composed a work for 100 metronomes.

Like Young’s 1960 Compositions, there’s a bit of playful jest in the work. But like Riley and Reich, there’s also a real fascination with units drifting in and out of phase, creating waves of consonants and counterpoints.

Watching the performance, there’s even an emotional pull to it. Unlike Young’s hypothetical eternal music, the steady ticks of the metronome eventually cease. As ever, entropy has its way.

Was the angst of the modernists a musical lie? No – but angst was only part of the story.

The modern world was vast and complicated.

It offered greater freedom and greater pleasures than ever before. It also invited chaos and destruction, and terrible injustice.

Without really thinking about it, the composers we now call minimalists were trying to evoke the grand complexity of human life through some very simple approaches to composition or production.

Whether by taking on a grand time scale, or systematically studying minute differences between parts, these individuals took the humming, churning, bustling, clamoring world around them and turned it into music for meditation or contemplation.

Sometimes they even added a bit of fun to the process.

The world would continue to hum and churn. Various factions would form, divide, unite, compete, and coalesce. Chaos would often erupt.

But sometimes, especially with the right frame of mind:

The madness around us can’t help but make us want to nod along and dance.

[I’d say ‘The End,’ but the song continues on somewhere](* I don’t believe anyone put a beat to Reich’s Come Out, but Madvillain got close)

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Bonus Beats:

I feel bad that I couldn’t mention Alvin Lucier in the piece, but I had to cut and simplify for length.

He was also an important pioneer of experimental audio recordings. His most famous piece is I Am Sitting in a Room from 1969.

The piece is just a short passage of Lucier’s speech playing on a loop.

Instead of breaking down from two tape sources drifting out of phase, Lucier lets his speech get more and more obscured by the resonant frequencies of the recording room.

Lucier struggled with a stutter, so the goal of the experiment was to smooth out the imperfections of his speech into gentle waves of noise. For listeners, it’s a powerful meditative experience that gets more hypnotic as it goes on.

Maybe before the fireworks and celebrations, sit in a room for a while and do some contemplation.

Happy 4th, everyone!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fAxHlLK3Oyk

I am sitting in a room listening to Alvin Lucier sitting in a room.

Nice addition!

This inspires me to get back to work on an experimental piece I haven’t touched in a while. I’ll let you know if it’s any good. I hope to listen to everything linked here, too, but thanks for the kick in the pants, Phylum!

Let me know if you need any vocal assistance.

I can do a decent pterodactyl shriek.

This reminds me of a rateyourmusic.com review of Phillip Glass’ Glassworks album.

I must say that I love this album. …But really, the biggest downfall for me was exactly HOW CONSUMING this music can be. Everytime “Opening” pops up in my shuffle, I feel the need to be introspective, drop everything and write about the desperation of society.

THAT CAN GET ANNOYING.

Thanks for this information. I can barely understand it, but it documents how part of art’s job is to push boundaries in every direction.

Ha! Philip Glass’ music is indeed featured in many a depressing drama, some of which are about the desperation of society.

His earliest work is less melancholy, but more emotionally muted overall.

This was a strange time for art and music, for sure. I have another piece coming soon that’s more of a case study rather than a whirlwind tour, in which I hope to convey the specialness of some of these weirder pieces and approaches. Though whether it’s actually successful in doing so is another matter.