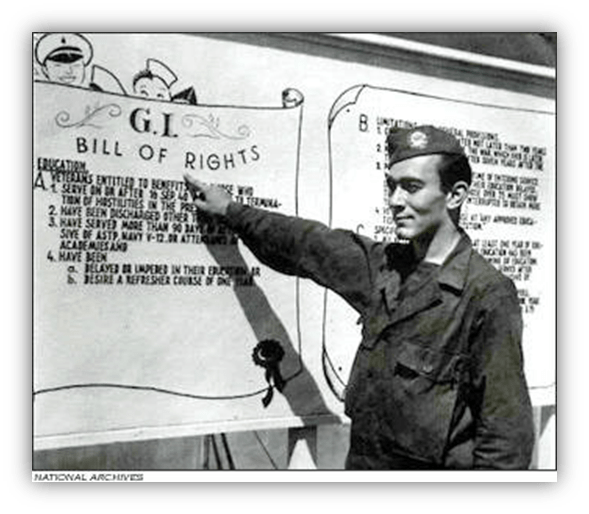

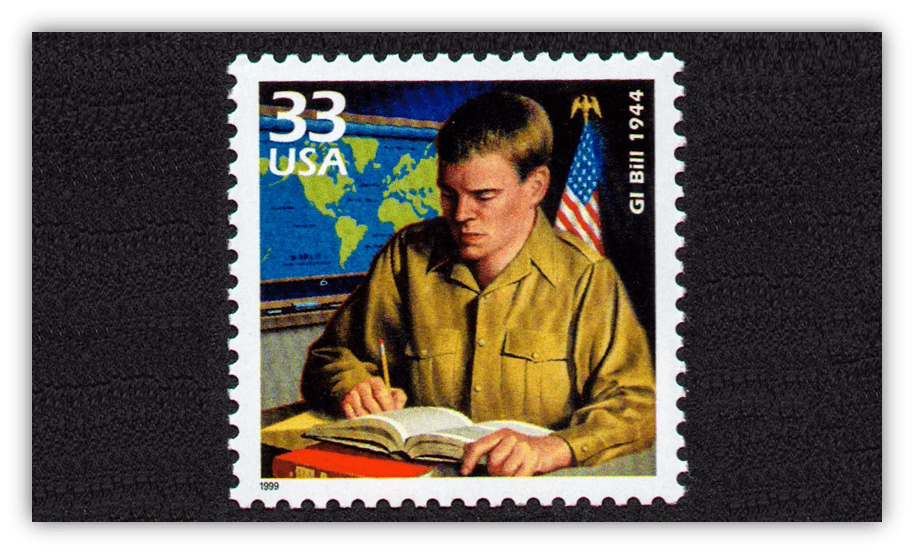

On June 22, 1944, President Franklin Roosevelt signed a new bill into law.

This was the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act.

It was a way to reward military veterans for their service in the war, and to help them reintegrate into civilian society.

One of the bill’s provisions was to pay for veterans’ higher education, including college tuition, room and board, and a living stipend.

As generous as they may seem to us, these educational benefits were of no great concern for the conservatives in Congress when drafting the bill.

Why? Higher education seemed an unlikely opportunity for the veterans to take.

Only 5% of people in the nation had a bachelor’s degree in 1944.

It was an option for the wealthy elite. And so the tax hawks instead put their focus on whittling down the new bill’s provisions for unemployment benefits and housing aid.

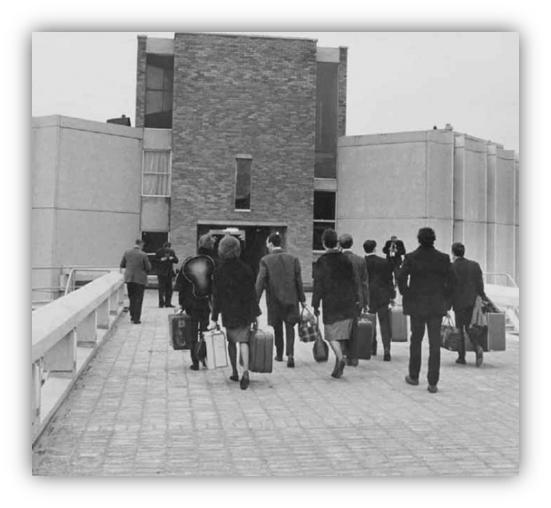

Little did those Congressmen know, people would actually take advantage of those educational provisions. Just two years later, about half of the student body of colleges and universities would be military veterans. And the numbers kept rising.

In the decades to follow, the educational provisions of the “GI Bill” would open the door for a full-on national transformation.

In this revolution, the children of farmers and laborers learned to become administrators, lawyers, scientists, inventors, and teachers. The military grunts from America’s backwoods came to supply the nation with a swelling middle class.

System Upgrade

Higher education would no longer be seen as a privilege for wealthy elites. It would be something of great national interest.

A public good. It was a new way to expand on the American Dream, as promised in Roosevelt’s New Deal.

“The campus is no longer on the hill with the aristocracy, but in the valley, with the people,” announced Clark Kerr, the University of California’s president. He and similarly-minded school leaders envisioned colleges and universities as representing new “knowledge factories” for the nation.

More schools were founded. Colleges expanded into universities. The original recipients of the GI Bill became the teachers and mentors for the younger generations.

As a result, innovation soared.

Businesses boomed. And America came out of the war as a thriving world power, thanks to its greatly expanded white-collar workforce, as well as its industry.

The Cold War was another big catalyst.

In the advent of Russia’s launch of Sputnik into outer space, Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson spearheaded legislation for further funding of higher education opportunities. This time, the conservatives only let the bill pass by replacing the federal grants with student loans. Still, scholarships were awarded, science grants were expanded, and the universities completed their transition into major hubs for research and technological innovation.

The Department of Defense remained a major source of educational funds, and they benefited most from the resultant technocratic class. A vast network emerged between academic researchers, private engineering and manufacturing contractors, and the Pentagon.

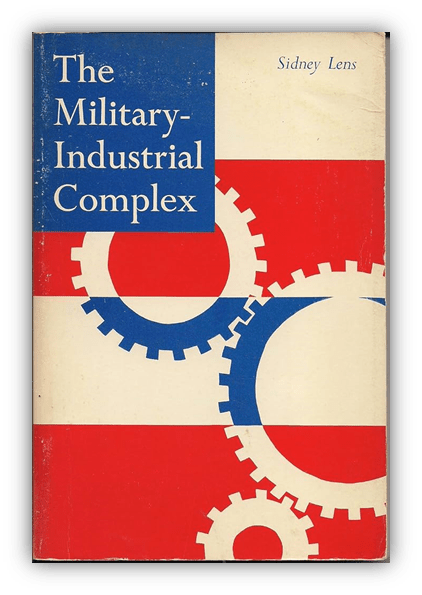

This rapidly growing network had no name until it was provided by President Eisenhower in his 1961 farewell address: the “military industrial complex.”

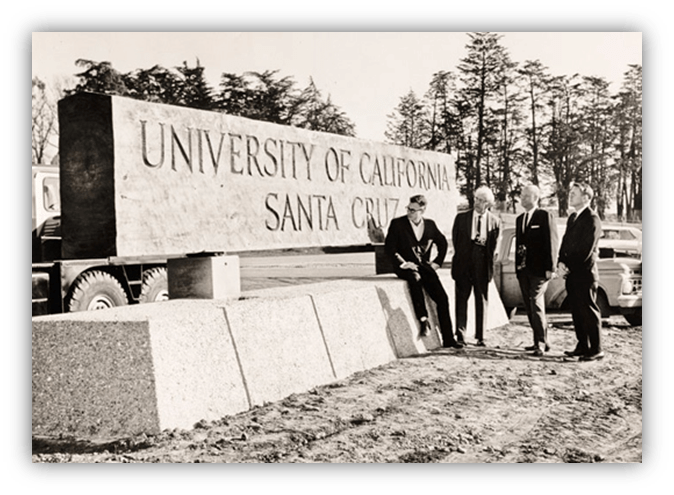

Meanwhile, education was taken to a whole new level of aspiration in the state of California. In 1960, a Master Plan for Higher Education was written by UC President Clark Kerr, and announced by Governor Pat Brown. Under this plan, college tuition for all California residents was almost completely covered by state taxes.

Based on their high school grades, the top performers would be awarded funds to attend the elite institutions of the University of California. The next highest performers would receive funds to attend the various state colleges.

And everyone else would receive funds for community college, which allowed for eventual transfer to higher institutions depending on performance.

This was envisioned as a system where everyone could have the same opportunities for success. A system driven by merit, rather than wealth and privilege.

Most states did not go quite as far as California in subsidizing higher education, but the Master Plan of 1960 did serve as a general model for other similar plans.

Education councils in England and France also drew inspiration from California’s model, though the resulting plans were distinct. Soon enough, various initiatives for mass higher education were underway throughout the Western world.

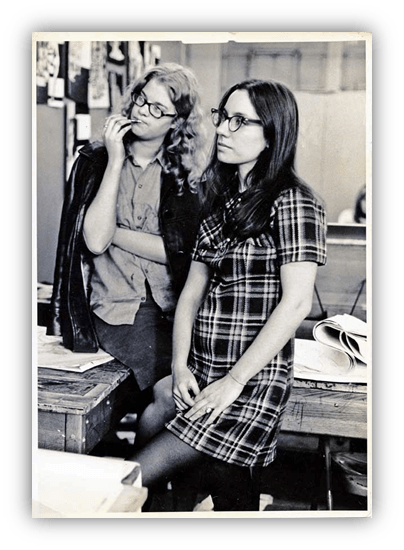

As time went on, attitudes toward higher education among faculty and students shifted. By the early 1960s, it was commonly regarded as something far beyond mere job training. It was a way to fill the nation with thoughtful and engaged citizens.

And so more emphasis was placed on liberal arts curricula. Thus a new generation of students, soon to be dubbed “Baby Boomers,” awakened to the issues of the world through the prisms of art, anthropology, world history, sociology, and political philosophy.

System Recall

This shift toward mass higher education had some major social implications. First, it carved out a distinct new period of development in the modern life span. A sort of deferred adulthood, at least within white collar culture. Undergraduate students could not enter the workforce for several years before earning their degree, so college provided a time of safe exploration before transitioning to career and family life as full members of society.

With extra leisure time and extra pocket money, the students naturally played crucial roles in the spread of youth culture fads like rock n roll, as well as later countercultural trends.

But the biggest social implications of higher education were related to democracy.

Specifically, the ideals about democracy that the students developed through their liberal arts education.

More specifically: how those ideals about democracy crashed against the ugly realities of the world around them.

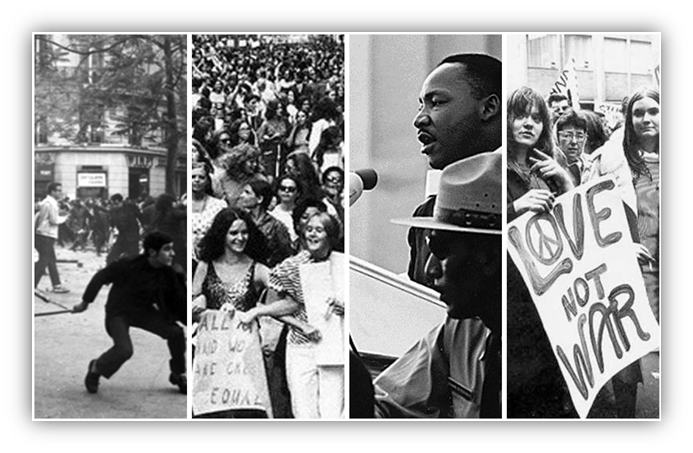

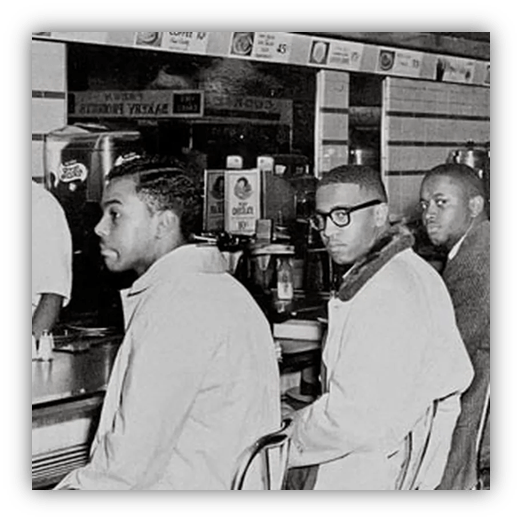

It started in the Jim Crow south. Inspired by the non-violent protests of segregation in local buses and high schools, four black students of North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University decided to start their own effort.

In February 1960, these four students occupied seats at the lunch counter of a local Woolworths store in Greensboro, NC.

They sat there all day until the store closed, then sought out more students to come with them the next day. Some of the students were eventually dragged out by police, or beaten by angry customers. But more protesters came to replace anyone who was taken away.

More sit-ins spread over the town, and across the south. A national ban on segregation would have to wait until 1964, but this legislation was due in no small part to the protests that the Greensboro Four had helped ignite. And some local establishments did in fact desegregate as a result of the sit-ins.

It became clear to young adults across the nation that they could play an active role in furthering American democracy. North or south, east or west, black or white, undergraduate students everywhere began to organize and coordinate in order to change their society.

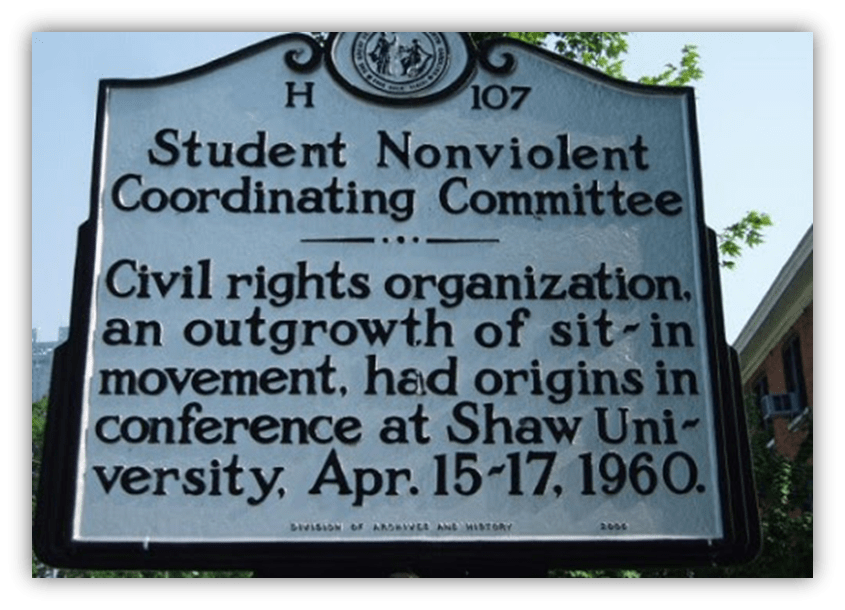

Stemming directly from the Greensboro sit-ins was the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordination Committee (SNCC), which started with 58 chapters in 12 states and kept spreading.

SNCC members played important roles in the freedom rides to desegregate interstate busing, and the march to Selma for voting rights. They also organized get-out-the-vote efforts among white citizens for the 1964 presidential election and beyond.

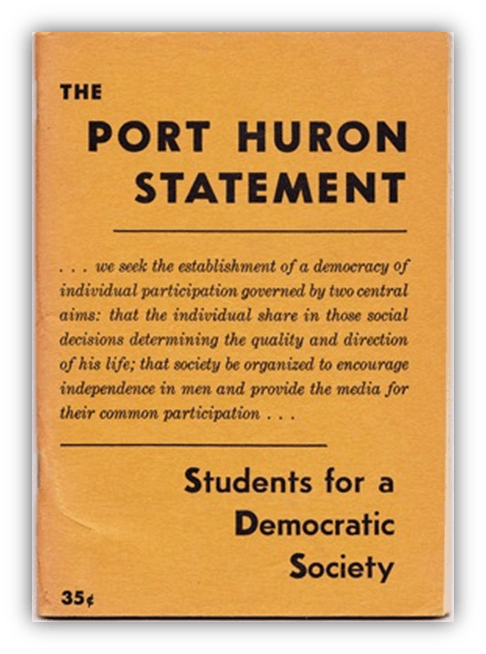

Then, a national network of students decided to take things even further. In 1962, the Students for a Democratic Society gathered together in Port Huron, Michigan to draft their movement’s manifesto.

The Port Huron Statement painted a very different portrait of America than previous generations had imagined. Over a whopping 25,700 words, the students described a nation that failed to live up to its own ideals.

- “The American political system is not the democratic model of which its glorifiers speak. In actuality it frustrates democracy by confusing the individual citizen, paralyzing policy discussion, and consolidating the irresponsible power of military and business interests.”

- “Not only is ours the first generation to live with the possibility of world-wide cataclysm—it is the first to experience the actual social preparation for cataclysm, the general militarization of American society.”

- “It is not possible to believe that true democracy can exist where a minority utterly controls enormous wealth and power.”

- “The arts, too, are organized substantially according to their commercial appeal; aesthetic values are subordinated to exchange values, and writers swiftly learn to consider the commercial market as much as the humanistic marketplace of ideas.”

(They even included an attack on the culture industry?)

(Theodor Adorno would have been proud!)

While the university presidents were hyping up their schools as knowledge factories, their trainees were plotting a strike.

…Actually, that metaphor doesn’t work. After all, labor unions were for the old school Roosevelt left. The Port Huron Statement laid the foundations of the New Left.

In this movement, economic concerns were still valid, but they often took a back seat to deeper social issues:

- Cultural representation.

- Militaristic colonialism.

- Systemic oppression.

- Freedom of speech.

It was in this new political climate that University of California’s president Clark Kerr found himself in the middle of a revolt. The transformational New Deal leader discovered with horror that cogs of his “knowledge factory” were starting to malfunction.

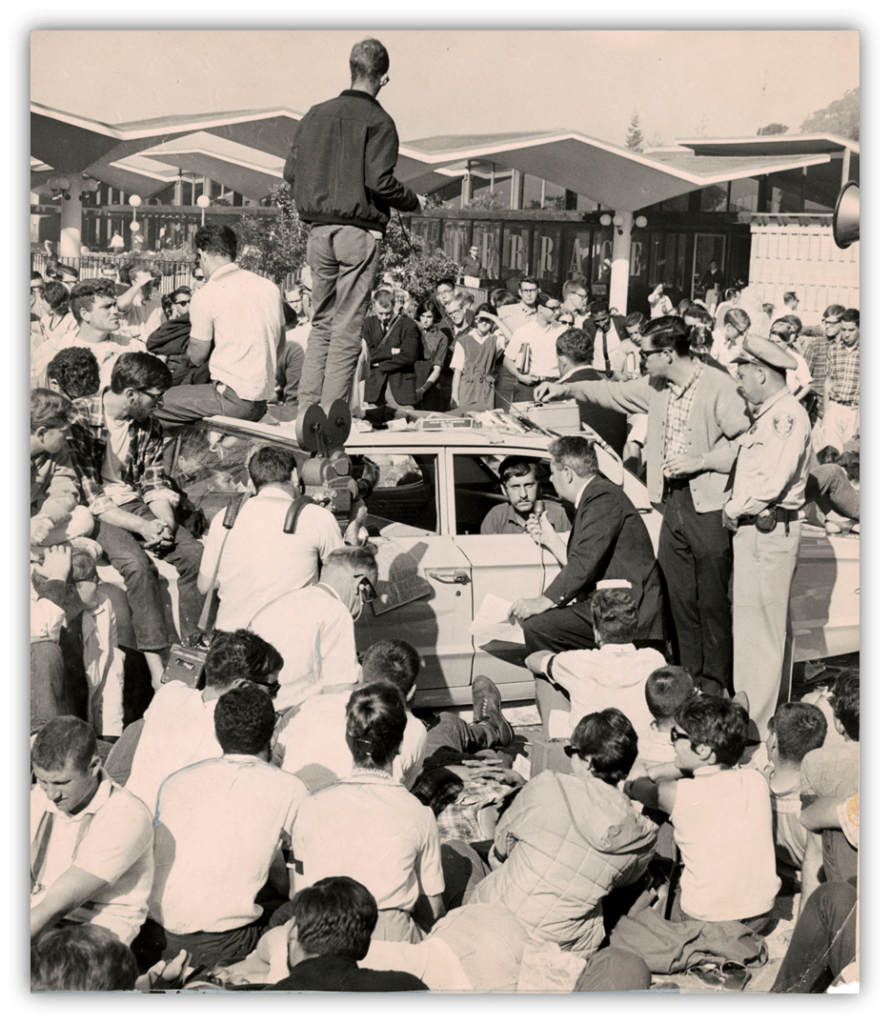

In 1964, the school introduced a ban on tables set up outside, to prevent disruptive organizing. A former student challenged the ban by setting up a table, then refused to present his ID to campus police.

When he was arrested, he let his body go limp, and so he was dragged into a police car. Students surrounded the car in solidarity, some of them climbing on top of the car–having removed their shoes to avoid vandalism charges. The arrested student remained detained in the police car for more than 30 hours, with up to 3,000 students demanding his release. He was finally freed and charges were dropped.

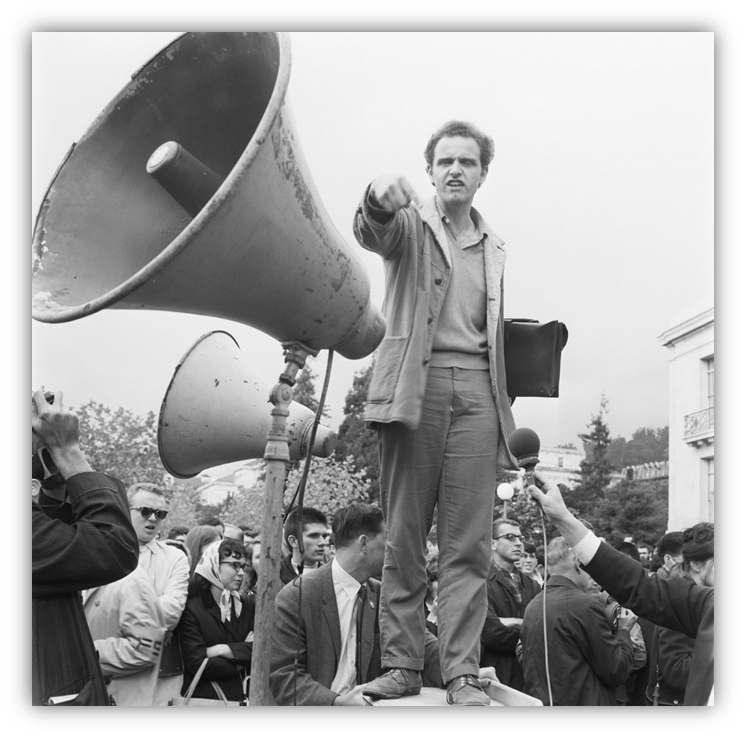

Then, a few months later, thousands of students gathered to demand that the Berkeley administration expand the school’s tolerance of free expression and protest.

The leader of this new protest, Mario Salvio, gave a speech that singled out the school’s president for his repressive policies.

But more importantly, Salvio helped convey to the world just how this new generation of students was feeling about the academic world they were being raised into:

“Well I ask you to consider — if this is a firm…and if President Kerr in fact is the manager, then I tell you something — the faculty are a bunch of employees and we’re the raw material!

“But we’re a bunch of raw materials that don’t mean to be…don’t mean to end up being bought by some clients of the University, be they the government, be they industry, be they organized labor, be they anyone! We’re human beings!”

“There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart that you can’t take part! You can’t even passively take part! And you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus — and you’ve got to make it stop! And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it — that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!“

While labor activists fought to reform the system, the New Left activists wanted to shut it all down and start anew.

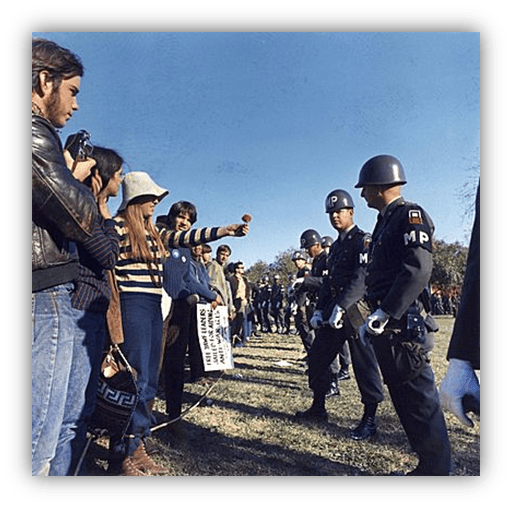

And this was all before US military operations in Vietnam escalated and incited mass unrest.

In the years to follow, students would come together and organize like never before. They may have been young. Somewhat pampered. Definitely idealistic. But they demanded active participation in their democracy. They demanded to be heard.

And boy, were they heard! Yes, they were...

But that’s a story for another time.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Bonus Beats: a mind-melting dose of Salvio:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W4vNmtlkGpY

I recognized Salvio’s speech from some other song but can’t bring it to mind. This is cool, though.

It’s amazing how many of these issue persist, perhaps because the forces against change have been pretty successful. They may slow things down, but they can’t stop progress forever.

Yeah, it’s scary how real the threat of reactionary forces have become.

I am more conflicted on the notion of progress, though. I think it’s a lot more complicated than I used to see it, and this series helps me wrestle with that complexity a bit.

Forward movement is perhaps inevitable, but there are many possible roads to take as we go onward. A meaning not originally intended in my title choice (was going more for the developmental/early adulthood aspect), but pretty apt!

I assume you’re not talking about the ORIGINAL Port Huron Statement, but the compromised second draft.

https://youtu.be/v9ULdvk2I5c?si=Onpat12J7PahI9oE

Yeah, unfortunately it was the major label debut.

I suspect you’ll be addressing this, but I’ve always been interested in how the business, education and government intersection of interests shaped generations of young people’s career aspirations — by continually redefining what the prerequisites were. My father graduated from high school in 1952 and spent his career in the computer/data industry without ever going to college. By the time I graduated from high school in 1981, I would have had to go to college had I wanted to follow in his footsteps.

I have some vague plans of where to take this particular thread in future write-ups. I wasn’t explicitly thinking about prerequisites per se, but maybe I would ultimately land in nearby territory. I’ll have to give it some thought.

I worry about the future of the humanities.

If a book like The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien gets banned, oh, boy.

Speaking of things we carry, I recently got a copy of Oryx and Crake…

About The Handmaid’s Tale: I’m mildly disappointed that Margaret Atwood is telling people I told you so. That doesn’t quite strike the right note for me. It’s not exactly something you should gloat over.

I’m rereading Anthony Doerr’s All the Lights We Can’t See. It’s on some banned books lists.

Your book post from two weeks past made me put down Firestarter and pick up To the Lighthouse. I couldn’t finish it. I don’t have the concentration. I just want to be entertained.

Well, you seem to put a lot of time and effort into art films. We’ve all got our limits and our preferences.

Me, I recently made some progress with Gravity’s Rainbow, but that was when I was stuck on airplanes for hours. Only 600 more pages of dream logic to go…

Speaking of dream logic, did you see I Saw the TV Glow? It seemed to be the most mentioned film on the mothership. I finally watched it. The commentariat is right; it’s good. All that’s missing from their plaudits is a Greg Araki mention. To me, the filmmaker is aware of Mysterious Skin.

Thomas Pynchon intimidates me so much, I haven’t watched Inherent Vice yet.

I’m not sure I considered how the college attendance explosion of the mid-century fueled social change when boomers were in school. Or that it also might have had something to do with kids “deferring adulthood” for 4 extra years. Good stuff.