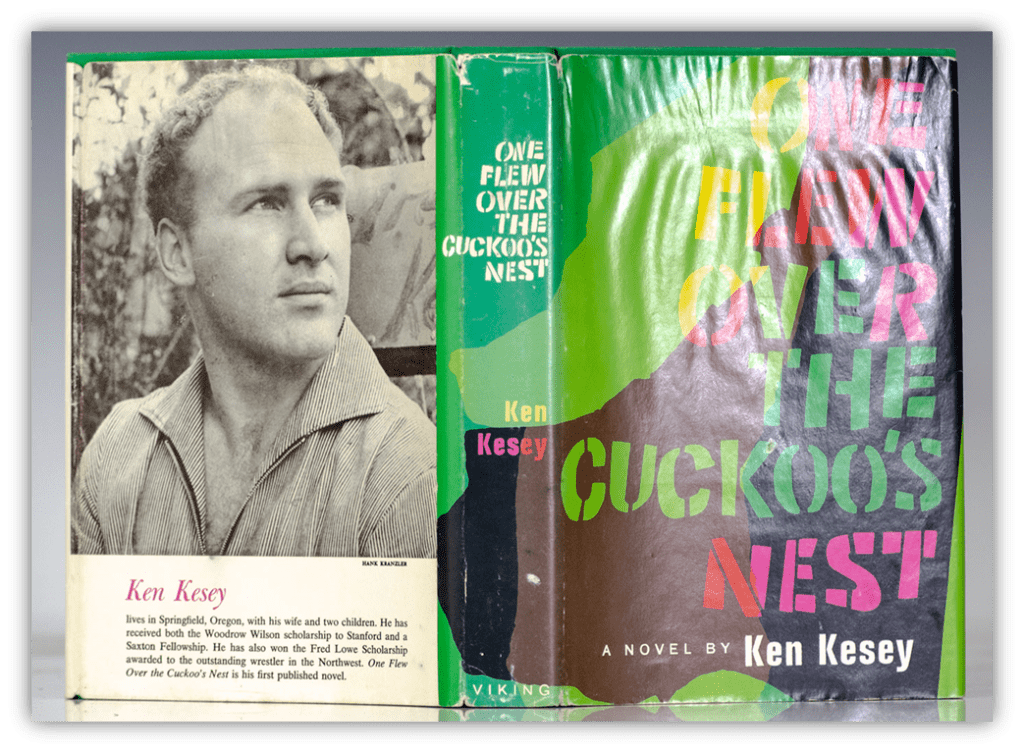

In 1959, a guy named Ken was working as a night aid at Menlo Park Veterans Hospital in San Francisco, CA.

It was there that he was invited to take part in a clinical research study.

In the study, Ken was given powerful substances.

These were drugs that distorted his perception of time and space, that obliterated his sense of self. The researchers observed his behaviors and transcribed his descriptions of the experience.

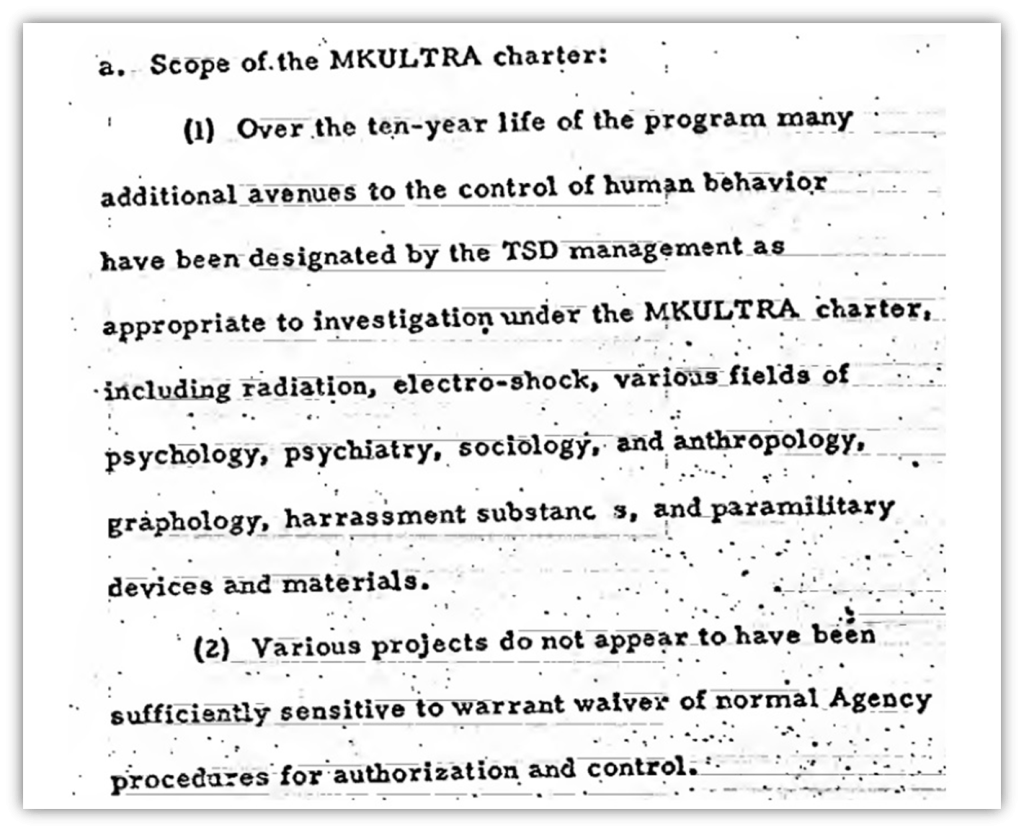

Years later, Americans would learn that the study had been financed by the CIA, and was part of a project to investigate the nature of brainwashing, named “MKUltra.”

Government agents pumping LSD, psilocybin, and other drugs into the bodies of American citizens? Just another day in the fight against tyranny, I guess.

Ironically, this secret project ended up creating a brand new insider threat for the feds to contend with.

Ken was never successfully brainwashed. But he had been forever changed.

He sought out more of the strange drugs the researchers had given him. This wasn’t a junkie seeking a fix, but a prophet whose scales had just fallen from his eyes. His spiritual journey was just beginning.

He began to write a novel inspired by his revelations at the hospital. That book, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, was published in 1962.

And in 1964, Ken and friends hopped in their insanely vibrant self-painted bus and rode eastward, from sea to shining sea.

Why? To reverse the westward expansion of the American empire, man. And to do a lot of drugs.

And more importantly, to share those drugs with people all around the country. Thus kickstarting what could be called a mass psychosis across the nation and the Western world.

Though I prefer to call said mass psychosis, “The Rise of the Hippies.”

Of course, Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters weren’t the only ones injecting this new madness into the culture.

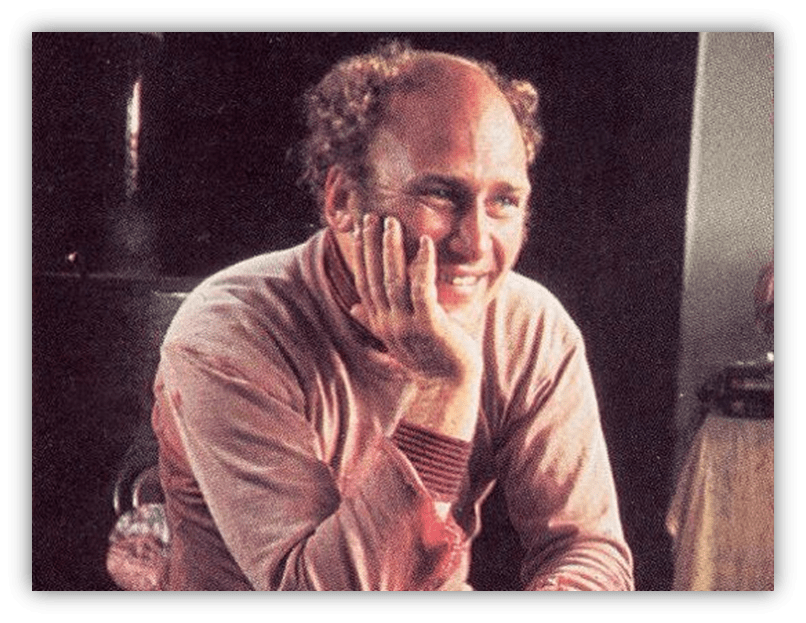

In 1960, a psychology professor tried psilocybin mushrooms for the first time.

He was inspired to formally investigate the effects of the drug in his lab at Harvard.

After a few years, his colleagues became worried that the studies were being run rather sloppily. The experimental groups weren’t randomly assigned. Undergraduate students were consuming psychedelics both in and out of the lab. And sometimes the researchers took drugs along with the participants.

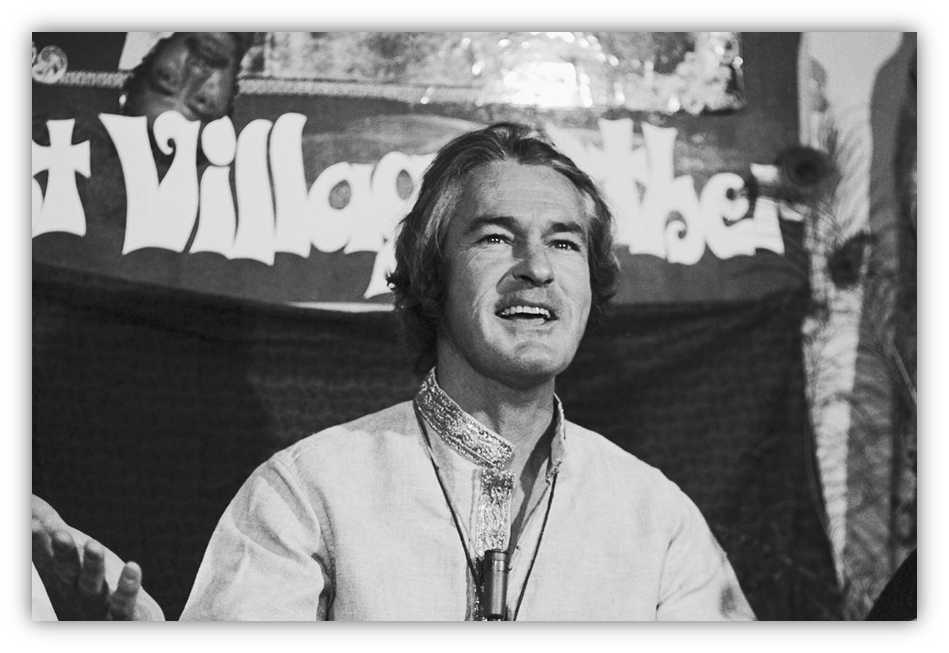

But Timothy Leary’s fame and notoriety only grew from there.

Some wealthy acolytes granted their new teacher access to their estate in Millbrook, New York.

And it was in this grand mansion Leary continued his “experiments,” i.e., gave psychedelic drugs to anyone who stopped by.

Notable guests included the Merry Pranksters, Charles Mingus, and the godfather of hippies: Allen Ginsberg.

By this time, Leary had transcended his former title of teacher.

He was now a guru for a new global counterculture. His sermons centered on escaping the drudgeries of mainstream society.

He encouraged everyone to “turn on, tune in, and drop out” of the norms and expectations that they were raised into. And many people heard his call.

“We tell young people today, drop out of school. Because school’s education today is the worst narcotic drug of all. Don’t politic; don’t vote. These are old men’s games. Impotent and senile old men who want to put you onto their old chess games of war and power. Drop out.”

“Tune in with natural things. Take off your shoes. Get back in tune with God’s harmony. Surround yourself with beauty and sacred objects. You can’t get caught in the conforming, rote lockstep which we call American society.”

This was a full-on bohemian revolution. The world had a generation of dreamers dead set on living life on their own terms.

So many of the posts I’ve written in this FREE4ALL series and in Dude, Where’s My Van? have centered on the weirdos who dwelled well outside of the mainstream.

When Marcel Duchamp debuted a urinal at a New York art gallery, most people never knew about it. If conservatives were fretting about something at that time, it was probably ragtime or jazz music.

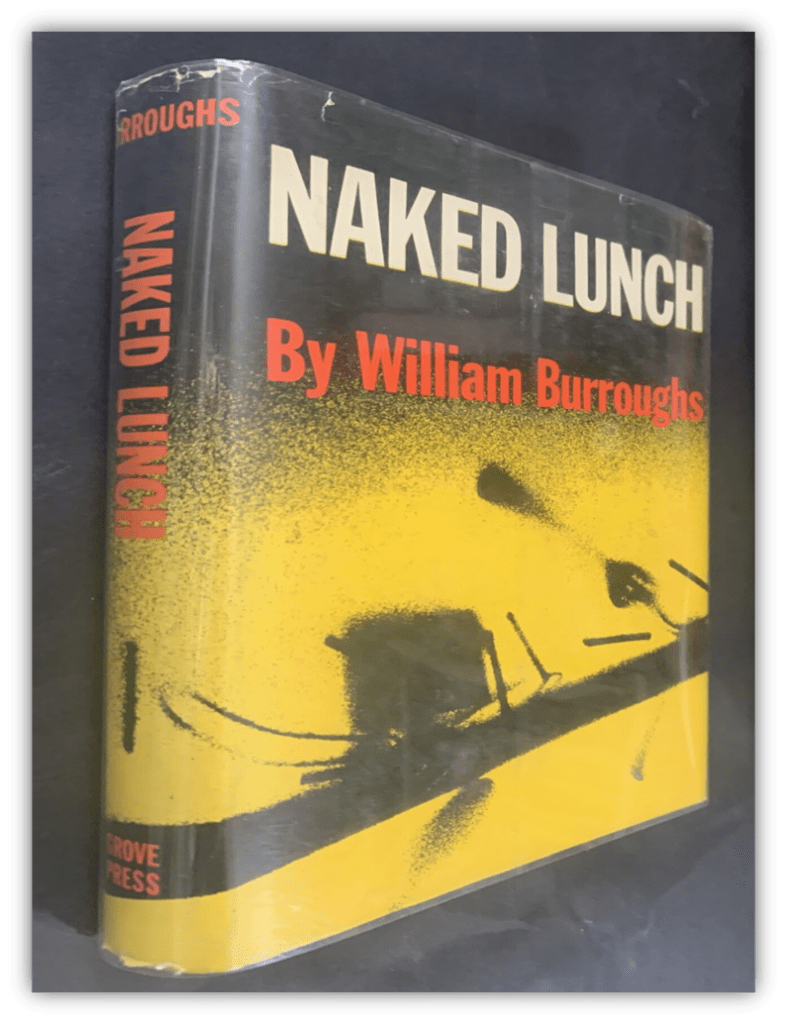

When William Burroughs unleashed his junkie subconscious onto the written page in Naked Lunch, the countercultural threat that most people worried about was Elvis Presley.

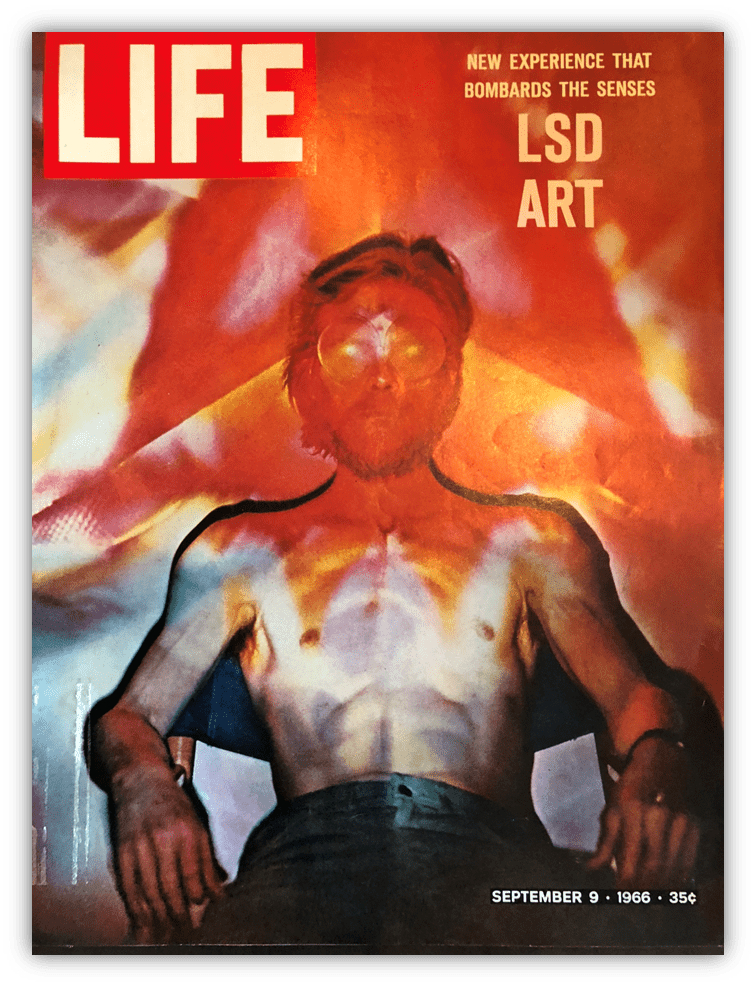

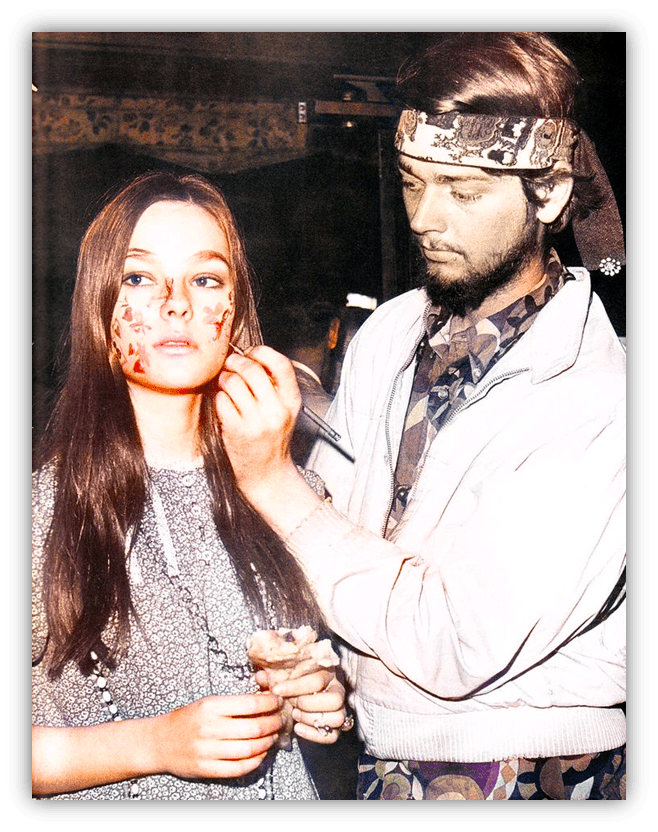

This dynamic changed dramatically with the rise of psychedelics and hippie culture in the mid-to-late 60s. Suddenly, the aesthetics of the avant garde were everywhere. On the streets. On school campuses. On the television.

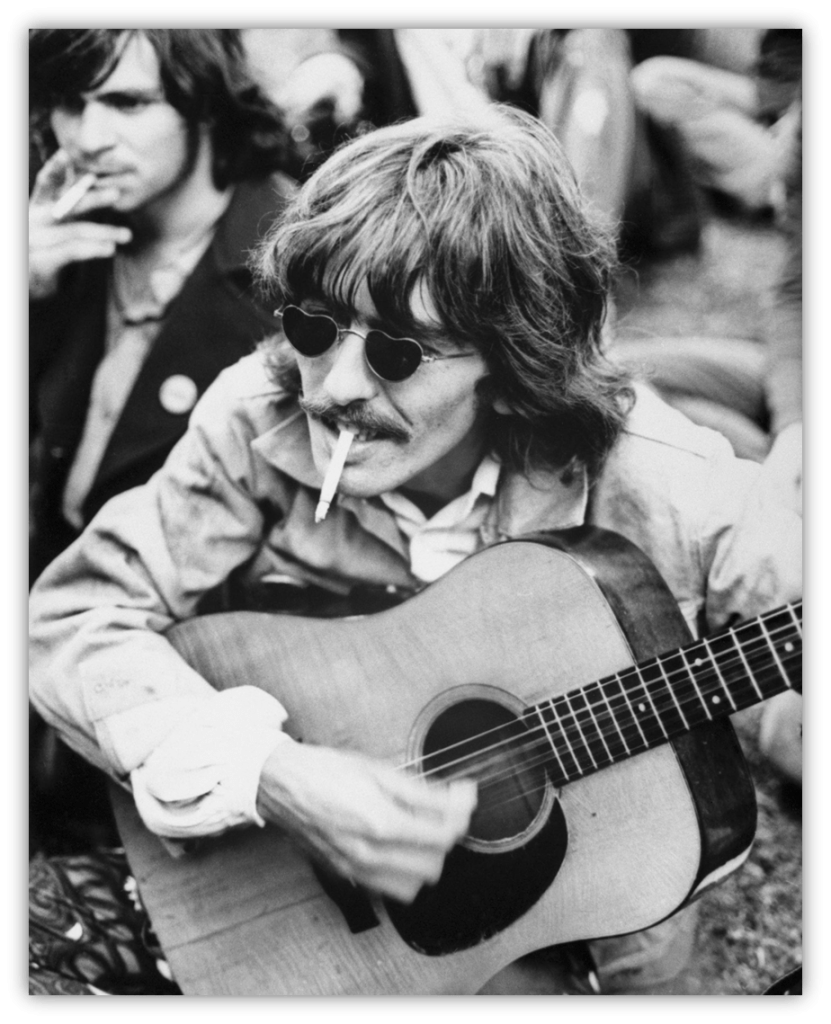

Not just in terms of hippie fashion, which shifted the appearances of the youth toward vibrant colors and natural, unkempt beauty. But also in art and music.

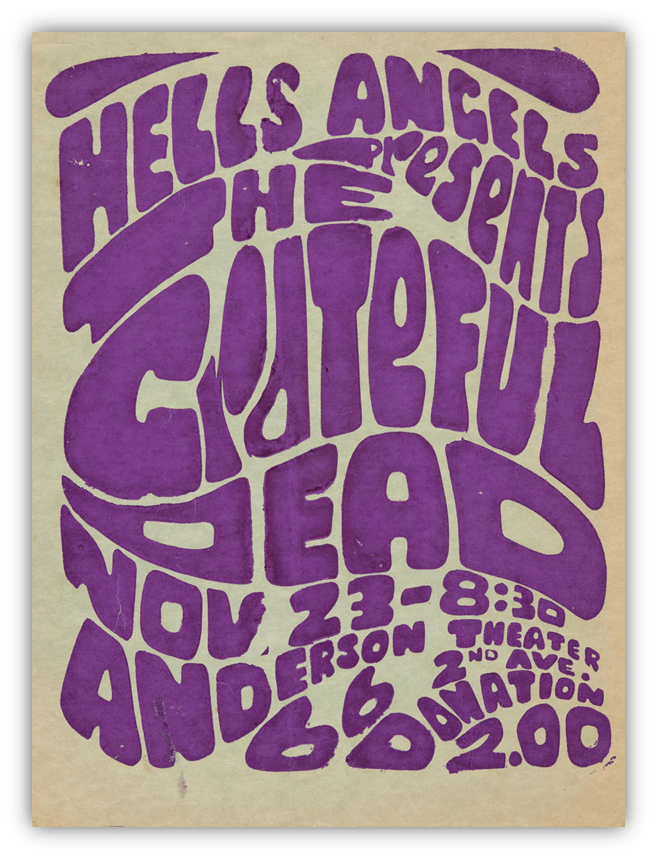

Psychedelic paintings and posters brought together Art Nouveau, Surrealism, and Pop Art with a DIY sense of mischief straight out of Dadaism.

Participatory conceptual works were once limited to John Cage and the Fluxus artists, but they got so popular that the notion of attending “happenings” soon became cultural kitsch.

And while the music was predominantly rooted in acoustic folk and electric blues, new bands infused their music with strange magics that they had picked up from modernist composers.

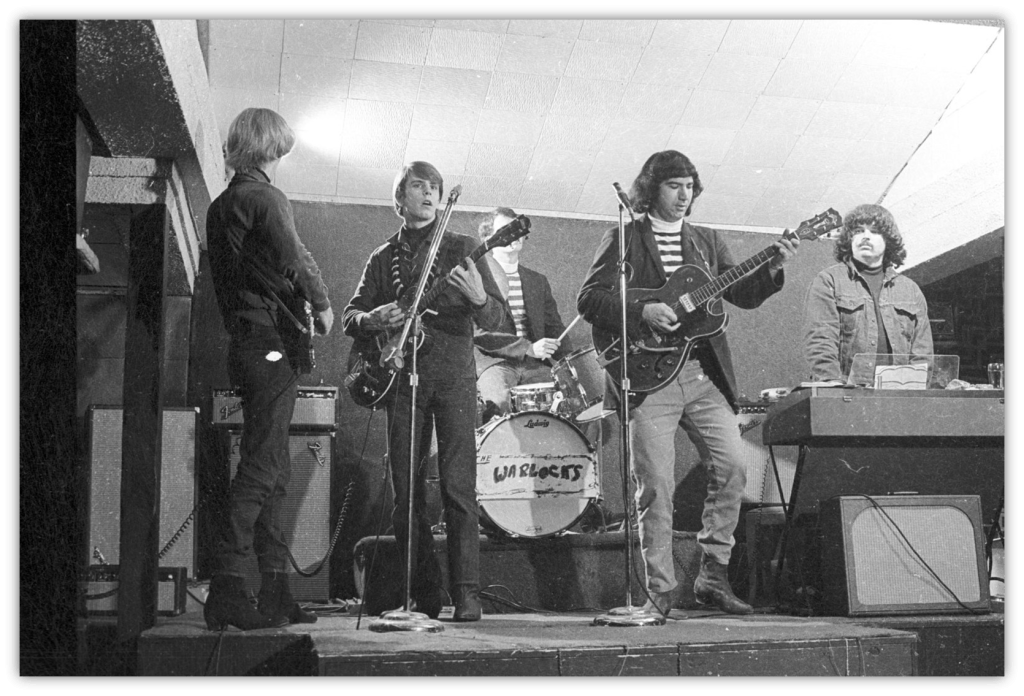

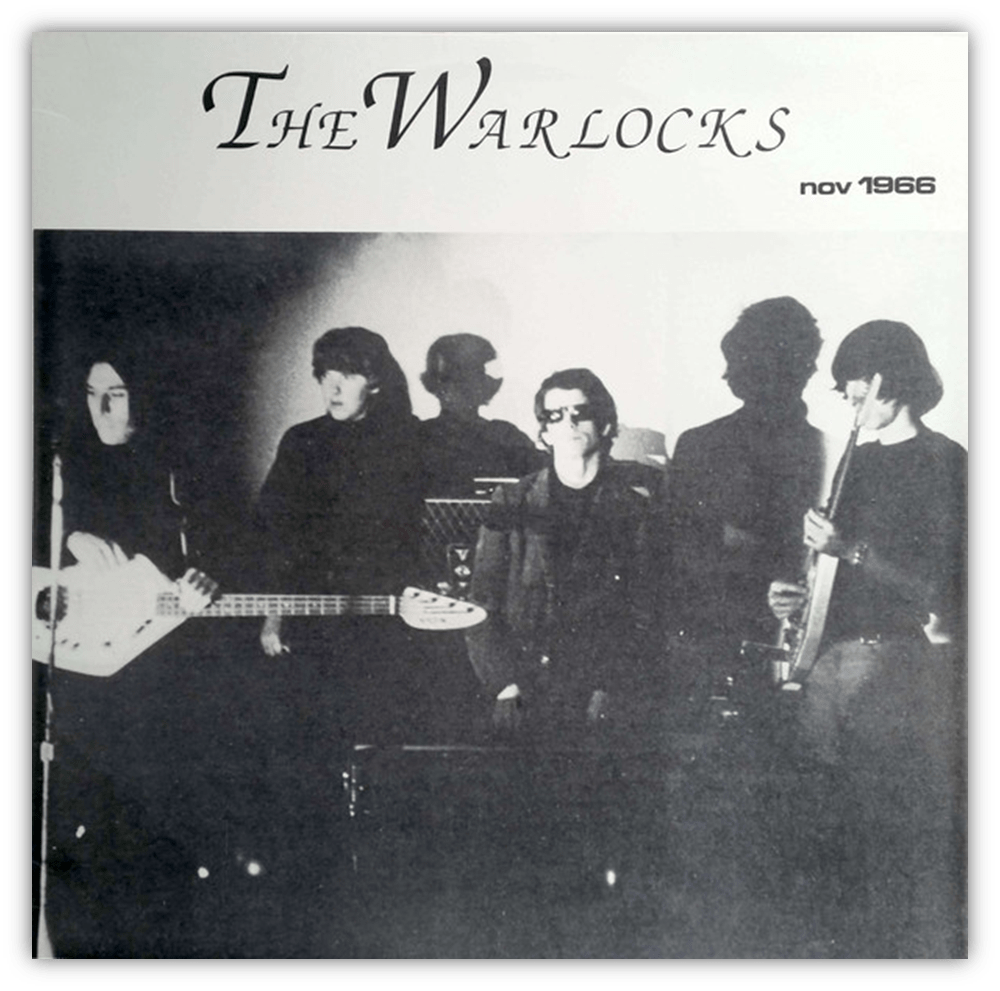

Here’s a spellbinding example: In early 1965, two bands were formed named The Warlocks. One in San Francisco, and the other in New York City.

The Warlocks in San Francisco started as jug band folk, but soon added electric blues and jazz to their repertoire.

Some members attended a course by Karlheinz Stockhausen, and learned about musique concrete audio production methods, which they used for spaced out sound collages in their studio recordings.

The Warlocks in New York City started out as acoustic folk, but they adopted rock and the amplified drone music of La Monte Young once a gifted viola player from Young’s group joined the band.

The group in San Fran became the Grateful Dead. They gave birth to the Haight-Ashbury hippie scene.

The Manhattan group became the Velvet Underground. And while they were more druggies than hippies, their dark, confrontational sound was no less psychedelic. Not to mention, they took part in a series of multimedia events known as “The Exploding Plastic Inevitable.” Far out!

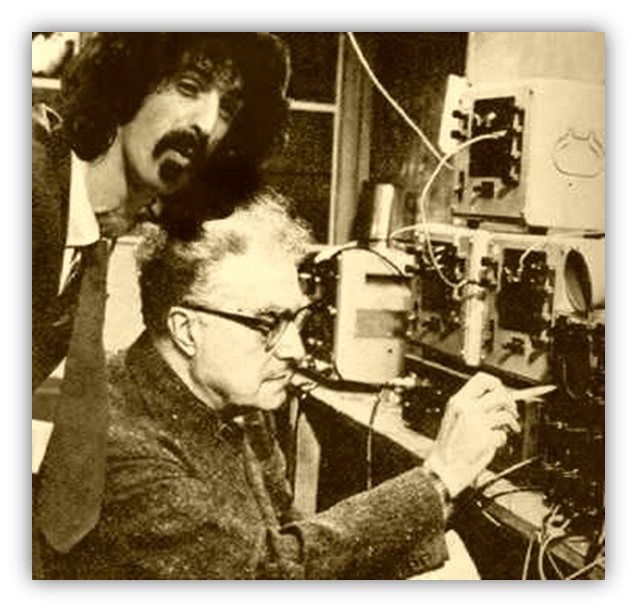

Frank Zappa was neither a druggie nor a hippie, but he readily identified as a freak.

And he imbued his rock and soul tunes with a sense of warped surrealism using methods showcased by his favorite composer, Edgar Varese.

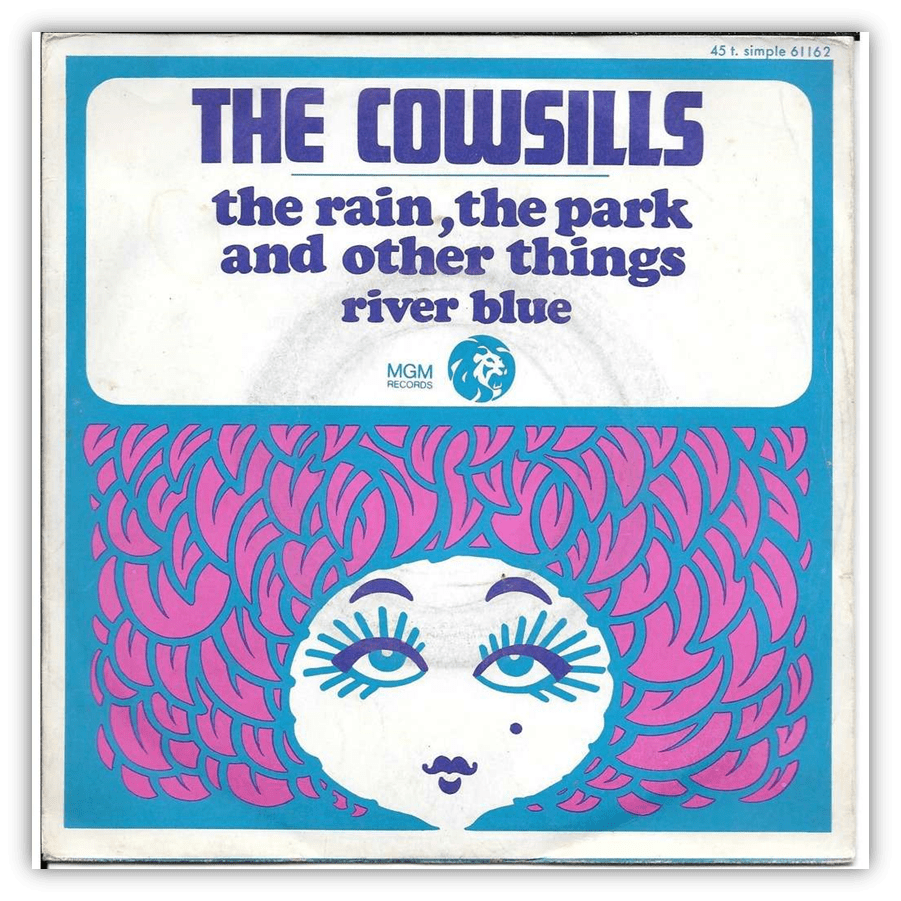

Bands like Jefferson Airplane, the Holy Modal Rounders, and The Jimi Hendrix Experience made similar sonic experiments on their own recordings. And the practice soon caught on as a countercultural trend.

In 1965, it was edgy to include a little guitar feedback in a rock n roll track. By 1968, it was fairly standard for songs to feature reversed guitar solos and other outlandish sounds.

Even the bubblegum bands started to get trippy. Which is pretty damn crazy if you think about it.

Yet psychedelic drugs spurred on far more than aesthetic choices. They led to radical changes in politics and lifestyle. Or, rather, the politics of one’s lifestyle.

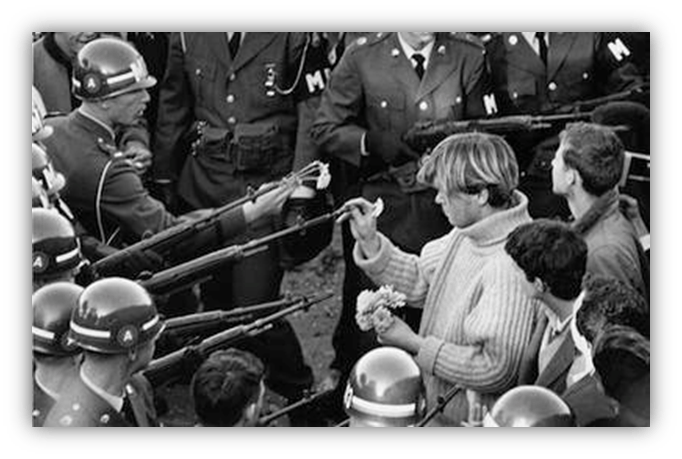

Most people who tripped on mushrooms or LSD came away feeling deeply connected to the world and to nature. They promoted a politics of gentleness and an aversion to aggression.

Horrified by the escalating conflict in Vietnam, the hippies began to protest their country’s role in the war. Some hoped to take the cause further, to end military aggression around the world with the example of their loving, open lifestyle.

Such utopianism was ultimately doomed to fail eventually.

Yet in truth there were darker currents from the very beginning, or at least tolerance of darker currents.

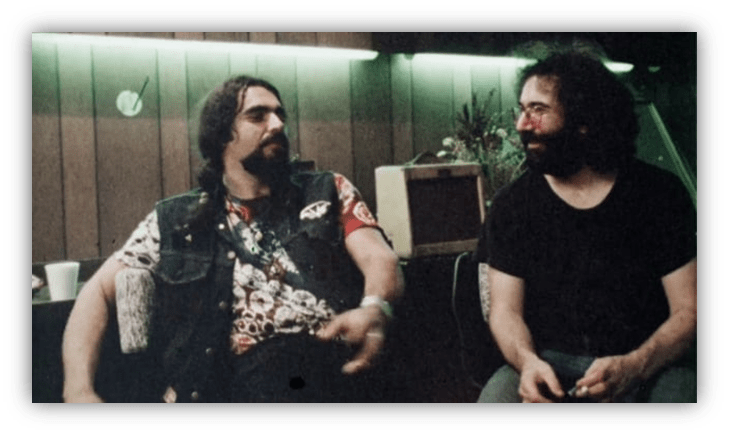

The Grateful Dead cultivated the Haight-Ashbury acid scene with help from the local Hell’s Angels gang.

There was cooperation and mutual respect among the groups, sometimes even friendship with individual Angels.

But there was always the threat of violence, and sometimes the threat became a reality. These guys took as much acid as the rest of them, but a utopia of peace and love was never their thing.

“The difference between the student radicals and the Hell’s Angels is that the students are rebelling against the past, while the Angels are fighting the future. Their only common ground is their disdain for the present, or the status quo.” — Hunter S Thompson, 1967

For their part, the members of the Grateful Dead respected the right of the Angels to live their own truths, even if they were darker truths.

“They’re honest and they’re out front and they don’t lie to you. They’re good people. They’re brutal, but their brutality is really only honesty.” Freedom, after all, goes both ways.

Whether for its utopian ideals or its unbridled freedom, the hippie movement disintegrated into shambles by the end of the decade.

Some more community-minded movement leaders had seen it coming:

“The hard-core hippie is a remarkable contradiction. He uses drugs to turn inward, away from reality, to find peace and security.”

“Yet he advocates love as the highest human value; love, which can exist only in communication between people, not in the isolation of the individual.“

“The hippies cannot survive as a mass group because there is no solution in escape. Most of them will regroup, either joining the radicals or drifting back into the mainstream.” — Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., 1968

In many ways, the hippie lifestyle embodied the pure ideal of personal liberty. But what value does liberty have when it’s at the expense of one’s community? What power does love have when you can’t effectively compel the world to change or improve?

Add to that the fact that the war in Vietnam dragged on, and actually escalated, rather than wind down. And then some hippie-adjacent tragedies, like the Manson Family murders and the killing of a man at a free concert in Altamont just a few months after Woodstock.

Soon enough, the notion of hippie peace and love were seen as relics of a more innocent, and more naive era.

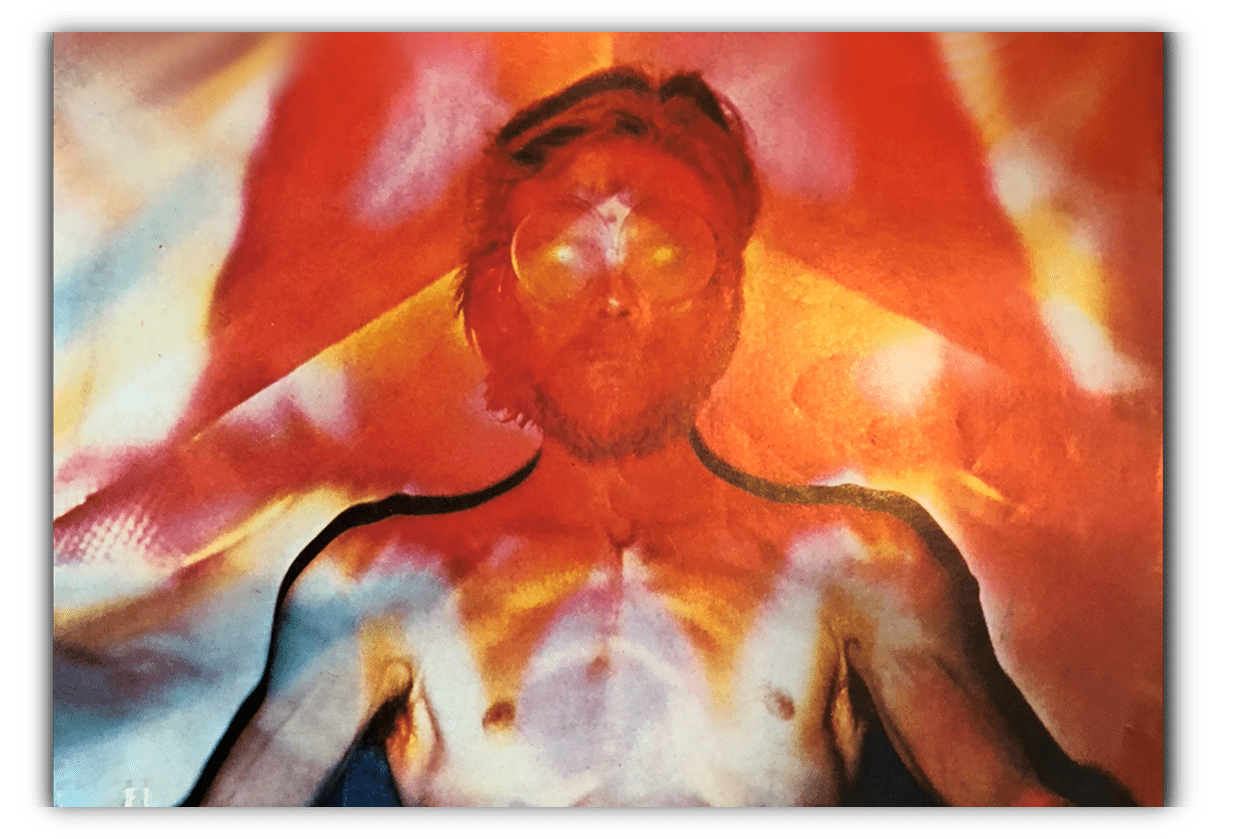

Of course, psychedelic drugs were never about peace or love, necessarily. Whether light or dark, they lay bare the inner truths of one’s mind. Collectively, the hippie movement helped to lay bare the inner truths of the new generation. Their aspirations, their defiance, their playfulness, their tenderness, their decadence, and their disillusionment.

A vision quest always has its perils. And this culture-wide trip proved to be downright seismic.

Every high must have its come down, of course. And boy, did things get dark in the years to follow. But I’d like to think that the experience led to some lasting changes in the culture.

More than Warhol, more than the Beats, the psychedelic craze of the 1960s shook up popular culture and made it bolder and more challenging than ever before. It made experimentation accessible to anyone who wanted a taste.

And whatever the ramifications, it forced everyone in our society to open their eyes and gaze upon the terrifying truth swarming all around us like angelic hosts in the heavens. We all finally saw those splendid, many-faced beings, like the prophets of old used to.

No matter who you were or what you wanted in life, be you free spirit or plastic, you now had to make like Jacob and grapple head-on with the naked grandiosity of the Weird.

And that’s just, like, a beautiful thing, man.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

I found this to be a balanced view about one of the most cataclysmic times in our modern history, although the present day certainly is having its moments.

That MLK quote is scarily dead on.

The song “Kid Charlemagne” by Steely Dan, loosely based on famed LSD producer Owsley Stanley, is a wonderfully vivid snapshot of the demise of hippie culture. It’s probably one of their best songs as well.

Have you ever read Season of the Witch: Enchantment, Terror, and Deliverance in the City of Love by David Talbot? It’s a fascinating history of San Francisco from the 60s to the 80s.

Someday I will write about an encounter I had with Timothy Leary when he was invited to speak at our college campus, unless I already did.

Rock on, Phylum!

Looking forward to that story!

Thanks! Currently at the airport, waiting to get home.

I haven’t read Season of the Witch, but it sounds like I need to check it out.

And I’ll definitely tune in for your Leary piece!

I saw what you did there, Phylum.

Great job explaining the effects of psychedelics on the culture as a whole. I’m not against a little experimentation with drugs — which is why I always wore goggles and a lab coat — but there comes a time when you’ve learned all you can and it becomes rote. Habitual, in some cases. That’s the fine line that many people don’t recognize. It’s really hard to tell when it goes from beneficial to detrimental.

Agreed. Sometimes it’s a good thing to shake things up, but it’s one of the worst sorts of habit to have.

Also, it’s probably a good thing for governments to refrain from dosing their people with experimental substances.

Also at an airport. Wave so I can buy you a coffee.

MK Ultra is among the most heinous things I’ve ever read about in my life. Learning the sheer evil it of it made me simultaneously outraged and full of despair.

And MK Ultra made it so easy to believe that the CIA was at least partially responsible for the flood of crack cocaine a couple of decades later.

I’ll soon be writing about a similar but distinct evil…I’ll be sure to cut my dosage with some lighter fare. Maybe some Blobby jokes!

Reading Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas made taking huge amounts of acid seem like a terrifying but hilarious adventure. I was happy to experience it through his words alone. Syd Barrett and Peter Green offered a counterpoint that too much of anything can have sad consequences.

I’ve not seen that Martin Luther King quote before but it sums it up. Dropping out only works if there’s enough people left behind to pick up the slack. As a mass movement it has built on obsolescence.