Jazz music in the 1960s?

It was the quiet rest of times; it was the loud burst of times.

It was a kaleidoscope of options. It was a battlefield of factions.

It was everything, essentially…except easy to summarize.

But I’ll do my darnedest, okay?

Recall that jazz was one of the first truly American forms of music.

It rose joyously from the shadow of the Reconstruction South, and was a dance craze in New Orleans by the time of the first World War.

It became a national pop novelty during the Great Depression.

And it became an indomitable international sensation during the US’s campaign against Hitler.

Throughout those early decades, the sound of jazz had shifted with the times and to please broader audiences. And it was always willing to mix in new styles and influences, even at the very beginning. Even so, there was no real question of what was and what was not, jazz.

That changed after World War II.

Bebop had been the first real schism, pitting older and younger jazz communities against one another.

Yet just a few years later, the radical pioneers had softened their approach, while jazz audiences actually grew to like a more adventurous sense of melody. The movement had largely survived this initial shock.

It was in the 1960s that the real splitting occurred, building from cracks that had first emerged in the late 50s.

Off Key: 1959 – 1964

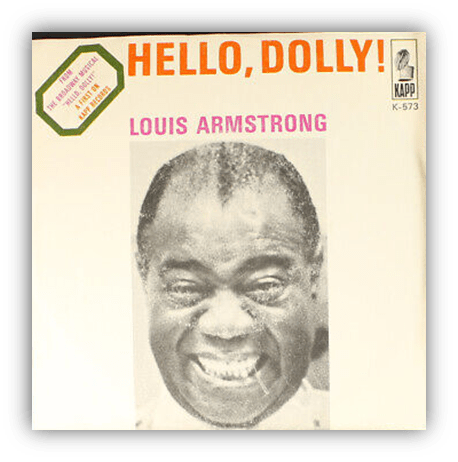

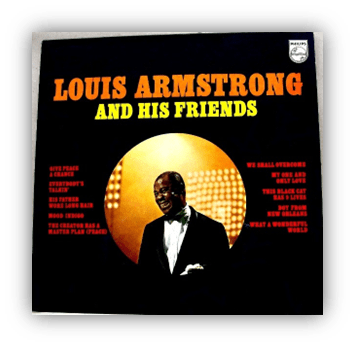

For the most part, jazz music wasn’t topping the charts anymore. A notable exception was “Hello Dolly” by the original jazz pop phenom Louis Armstrong.

This was the first new single he had recorded in 12 years, though his 1955 take on “Mack the Knife” had recently gained popularity thanks to the Bobby Darin cover.

But more often than not, young audiences were listening to rock n roll bands, girl groups, or easy listening variations of the same.

One new sound that took the jazz and pop worlds by storm was the slow tropical sway of Bossa Nova.

This style had its roots in Brazil. In 1956, writer Vinicius de Moraes met pianist Antonio Carlos Jobim and commissioned him to write music for his upcoming play, “Orpheus of the Conception.”

The music Jobim wrote was based on Brazilian samba, but some of the songs featured a soft melancholy that departed from the festive Carnival setting of the story.

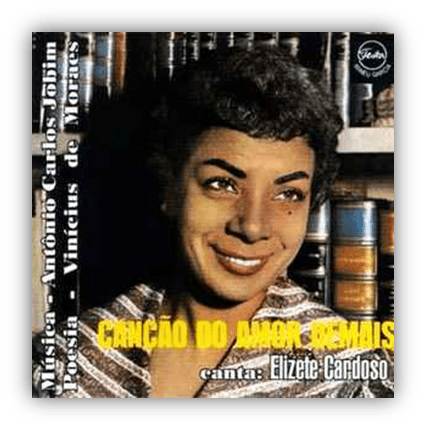

In 1958, Moraes and Jobim worked together on an album for the popular singer Elizete Cardoso.

Cançao do Amor Demais was the first album done in the bossa nova style, and also the first to feature the gentle guitar rhythms of Joao Gilberto.

Then in 1959, Joao released his own bossa nova album, Chega de Saudade, the debut of his famously soft, silken vocals. The formation of the style was now complete.

Jobim and Gilberto had been influenced by earlier cool jazz musicians like Stan Getz and Chet Baker, so it’s perhaps not surprising that this elegant new sound would eventually be championed by a similar crowd.

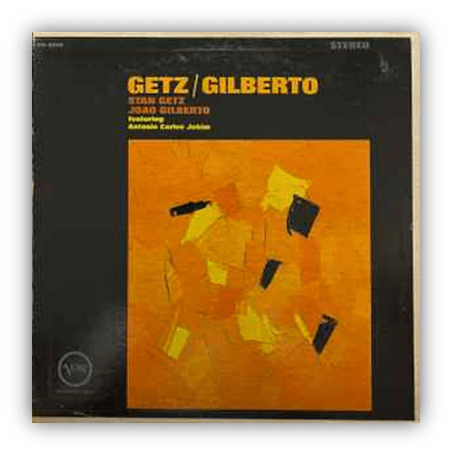

In 1962, Stan Getz recorded his own version of a song written by Jobim for Gilberto, “Desafinado” (Portuguese for “off key”). With this single, the US bossa nova craze began in earnest.

Getz and Gilberto famously recorded their own album together in 1964, and Getz/Gilberto remains the definitive statement of the style.

Its soft tones and gentle melodies made for perfect easy listening. Yet the insistent rhythm and sultry mood spur on slow dances and romance. It’s no wonder that so many other jazz musicians jumped on the bossa nova trend.

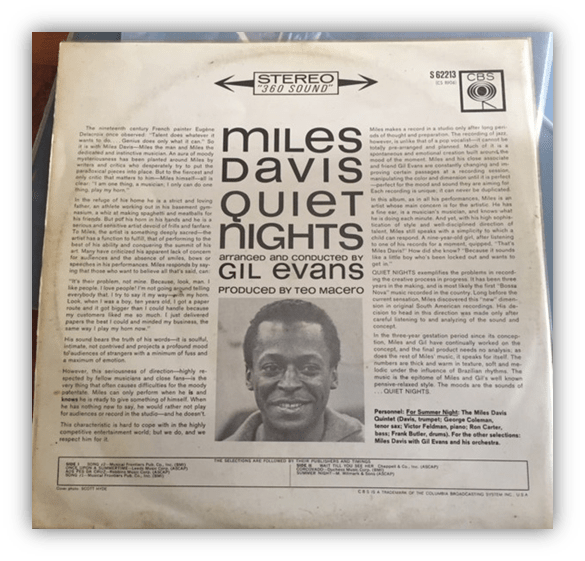

Including veteran trumpeter Miles Davis, although he was angry at his producer for releasing those sessions.

Like so many jazz musicians in the post-bop years, Davis wasn’t above the idea of making a profit, but he wanted to do so on his own terms, without any sort of pandering. And he did so with aplomb throughout the 60s, building on the success of his earlier breakthroughs.

Davis had been in the jazz scene since Charlie Parker’s first recordings in 1945. Yet in the decade to follow, he proved restlessly creative, constantly changing up his formulas. He helped develop cool jazz, as well as the slower and bluesier alternative to bebop: hard bop.

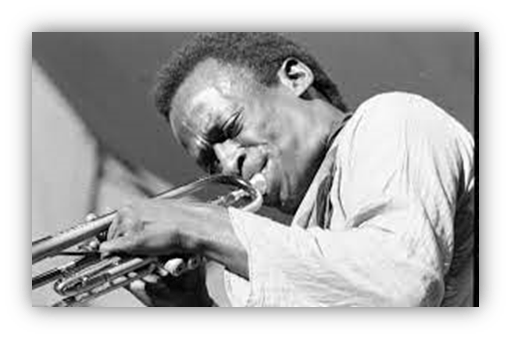

Throughout it all, Davis was steadily refining how he played his trumpet.

In contrast to Louis Armstrong’s bouncing melodies or Dizzy Gillespie’s fluttering frenzy of notes, Miles employed a quiet minimalism in his trumpet solos.

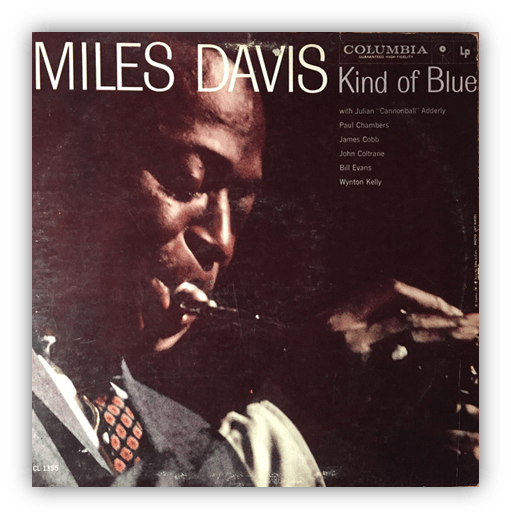

In the summer of 1959, just one month after Lady Day passed away, Davis had released what was perhaps his greatest work. Kind of Blue was an album that excited music critics and audiences alike. And more importantly, it inspired other musicians to follow in its footsteps.

Beyond perfecting his expressive phrasing, Miles used Kind of Blue to try out a new approach to writing and playing with his band.

Ever since the rise of bebop, jazz music featured melodic passages that were mostly improvised, but the musicians always tied those improvised lines to chord progressions specified for a given song, within a given key.

Miles chose instead to center his songs on musical modes, allowing more fluidity with respect to key. Modal jazz caught on as an intellectual exercise among musicians, and many other jazz bands followed suit in the early 1960s.

But the magic of Kind of Blue came from the fact that such experiments don’t sound like exercises at all. They sound intuitive. Heartfelt. Naturally beautiful.

Paramount to the album’s magic was the roster of musicians that Davis had assembled for the recording. His band for the last few years had included Jimmy Cobb, Paul Chambers, Cannonball Adderly, and a young tenor saxophonist named John Coltrane.

For Kind of Blue, he also added the pianist Bill Evans.

It was Evans’ delicate, dreamy melodicism that had originally inspired Davis’ forays into modal composition. His playing set the standard for many big jazz pianists to come, from Vince Guaraldi to Herbie Hancock.

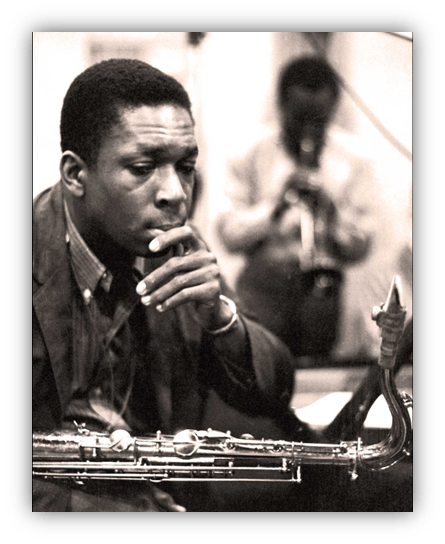

But it was Coltrane on the tenor saxophone that was the boldest ingredient.

While most of the band pursued soft and steady grooves, Coltrane’s sax solos were often bright and muscular. Rather than upending the session, he helped to emphasize the fluid and daring feel of modal jazz.

And being the polar opposite to Davis’ introverted style, he also provided a crucial sense of balance to it all.

This particular band would not record together again, but they would all enjoy critical and commercial success in years that followed. Davis brought in the new decade by fusing modal jazz with Spanish flamenco music, and then moved on to a flurry of other projects. Evans led his own band, and even hit the charts with his lovely “Waltz for Debby.” Coltrane would also form his own band. And he would start to release his own masterpieces.

At the same time, plenty of other jazz musicians sought to strike the balance between artistic innovation and popular appeal that Kind of Blue did so perfectly. Perhaps the closest was Dave Brubeck Quartet’s Time Out from 1959.

This took cool jazz into new territory via its focus on unconventional time signatures, but its strong sense of melody, particularly in the single “Take Five” helped it become a hit.

There was also Herbie Hancock’s Afro-Cuban fusion in “Watermelon Man” and “Cantaloupe Island,” not to mention Vince Guaraldi’s wildly popular tunes for Charles Schultz’s Peanuts.

At the same time, a new generation of musicians were coming into their own, and they had no desire for commercial success or popular appeal. Even more than the beboppers who came before, they wanted to take jazz to new extremes of expressive freedom.

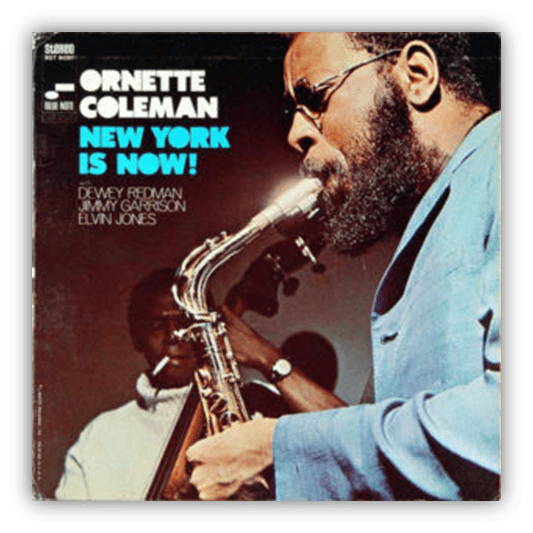

First came albums from pianist Cecil Taylor and saxophonist Ornette Coleman in the late 1950s.

These releases were fairly conventional compared to what would come in the 1960s, yet they showcased a greatly expanded sense of tonality compared to most jazz music of that time.

Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come introduced a particularly raw and loose style of playing. While melodic, the band almost sounds like they are about to fall apart. Coleman and his friends then released an album of collective improvisation that was so unbridled and so unruly, it was outright cacophonous. This was Free Jazz from 1961. Beyond perfectly embodying the new generation’s approach to jazz, the album provided them with a label to describe their revolutionary sound.

Some older musicians, such Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk, thought that this “free jazz” was just regular jazz played poorly. Still, other veterans found a primitive sense of emotional power in the new style of playing, especially bassist Charles Mingus and the drummer Max Roach. While they never made music free enough to merit the new label, they would soon release their own challenging works of avant garde jazz.

Roach’s We Insist! from late 1960 was a potent early example of avant jazz getting political. Featuring his wife Abbey Lincoln on vocals and several guests including the legendary Coleman Hawkins on saxophone, We Insist progresses as a slow burning fuse of anger at white resistance to black civil rights.

In a section titled “Protest,” the lit fuse explodes into rage. Abbey Lincoln veers suddenly from solemn wails into shouts and screams amid Roach’s violent bursts of rapid-fire drums. This performance predated Yoko Ono’s freewheeling musical experiments by a decade. Even now, the piece has the power to shock listeners out of their complacency.

Along with Roach, the young free jazz musicians set about cultivating a new consciousness for black men and women. Whether the rest of the world could keep up was not their concern.

I Think To Myself: 1965 – 1970

In the second half of the decade, the innovations of the radicals began to take root. Even in the pop charts, as the British Invasion paved the way for a new youth counterculture. And it took root among the jazz establishment as well, whether they realized it or not.

In the summer of 1965, Miles Davis showed off a new band with the release ESP.

This band featured Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams. For the most part, this new band simply helped Miles continue his exploration of modal jazz vamps. And that’s fine, it’s great stuff!

Yet Miles’ playing in this and later releases seems ever so slightly expanded in his tonal palette. Perhaps the rising flood of free playing was starting to lift all boats. If so, it’s unlikely Miles was actively absorbing the work of the young free jazz artists, and perhaps was absorbing the work of his old bandmate, John Coltrane.

Coltrane himself didn’t immediately adopt free jazz ideas in his own work, but he went down a path that became increasingly unstructured.

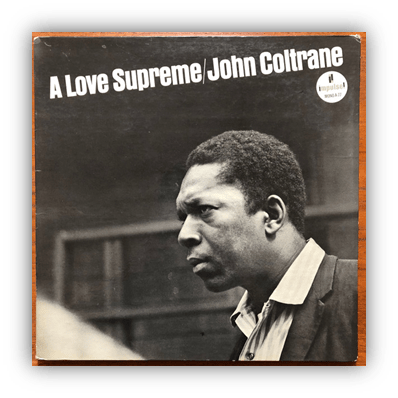

A Love Supreme from early 1965 was his magnum opus, his most sincere expression of his spirituality to date.

The music here was highly accessible, but could sometimes veer into fits of screaming, ecstatic abandon. As such, it served as a sort of liminal gateway, connecting his relatively grounded early work to his completely out-there later work.

Coltrane would ultimately take free jazz to the higher planes of sonic daring. And new levels of sheer power. No one could match Coltrane in terms of energy and force, so when this train veered off the tracks, the results were explosive.

Coltrane had long sought to expand his understanding of melody, harmony, and other aspects of musical structure in order to transform his approach to jazz soloing. One major influence in this respect was the Indian raga music of Ravi Shankar, which he first encountered in the late 50s. Coltrane studied Indian classical music, and he met Shankar in 1964. Yet it was when he had embraced free jazz in his music that those debts to Indian ragas became more and more overt.

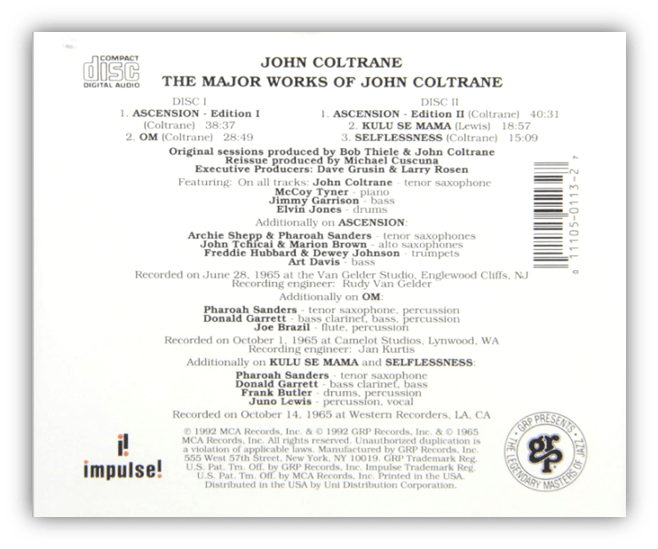

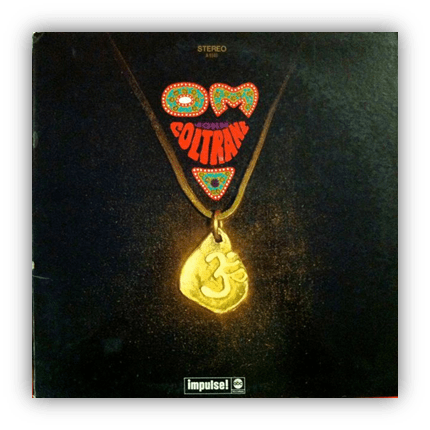

Om actually quotes from the Bhagavad-Gita before descending into freewheeling chaos.

It was recorded in 1965 (though it was released 3 years later), and yet it feels perfectly of a piece with the psychedelic freak-outs of the hippies that would soon come.

Both groups were interested in unbridled personal expression flavored with Eastern mysticism.

Yet by the time of Om’s release, John Coltrane had been dead for one year. He died of liver cancer at the age of 40. As such, the otherworldly sounds of later works such as Om and Interstellar Space can’t help but feel eerie, as if Coltrane’s spirit has been summoned in a séance to float through our ears before ascending back to heaven.

Other musicians pursued their own spiritual journeys through free jazz, such as Pharoah Sanders and Alice Coltrane. And they can be just as compelling and terrifying as shamanic rites as Trane’s original experiments.

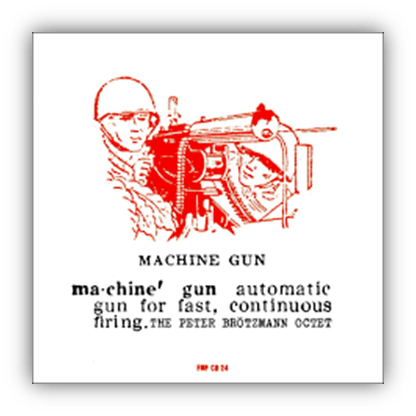

Others, such as Peter Brotzmann’s Machine Gun from 1968, seem like purely aggressive assaults on the listener.

Free jazz was always radical in sound and philosophy, but in the late 60s it culminated in some of the most extremely punishing music available.

Some of this later free jazz was adjacent to the hippie scene and other celebrity musicians, but for the most part it was on the outskirts, and deliberately so.

It wasn’t until 1969 that someone actually fused jazz music with the sounds and sensibilities of rock.

Early in the year, Miles Davis’ drummer Tony Williams had recruited a young guitarist to play for a new band called Lifetime.

However, once Davis had heard this John McLaughlin jam out, he was compelled to have him play guitar for his own new project.

McLaughlin and percussionist Joe Zawinul joined Davis’ quintet, which had been flirting with electric keyboards for a few years before deciding to go all-out on contemporary sounds.

They improvised together for long vamps during these recording sessions, then producer Teo Macero cut up the tape reels and reassembled them to create new arrangements. Musique concrete was as old as bebop, but it took the advent of psychedelic rock for these techniques to finally cross into the world of jazz.

The result was In a Silent Way, a work of electric jazz that was equally driving and spacious. Undoubtedly a precursor to the “krautrock” of Cologne, Germany. It was also moderately successful, allowing Davis to enter the charts for the first time in four years.

The band then decided to take this hybrid sound into the stratosphere.

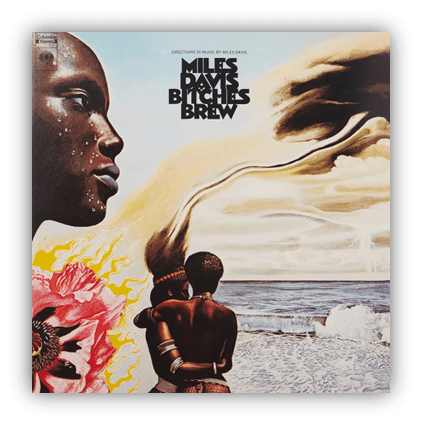

On Bitches Brew, free improvisations explode into stomping rhythms with a rock backbeat. The playing was so freewheeling, in fact, that it seems Davis had finally made some peace with free jazz.

It wasn’t true free jazz: the music was carefully designed, often minimal in delivery, and reassembled through tape edits. Nevertheless, Davis’ notion of tonality opened up dramatically here, and the resulting cacophonies could indeed be terrifying.

Amazingly, Bitches Brew ended up being Davis’ best-selling album since Kind of Blue. Perhaps the time was right for untethered sonic adventures.

In the decade to follow, every member of this Davis band would subsequently contribute their own hybrid experiments, making “jazz fusion” a dominant presence in popular music. At this point, jazz had to play catch up with the next new things rather than the other way around. But jazz artists had found a way to remain active in the cultural discourse. They weren’t inspiring many kids to play jazz anymore, but they got rock musicians to think outside the box in terms of experimentation and improvised playing.

By the start of the 1970s, society had plenty of anger to go around, but Black solidarity had become increasingly important. Appropriately, the various generations of jazz musicians seemed to come to terms with one another. For a time, at least.

In the summer of 1970, Ornette Coleman and Miles Davis both participated in a recording session with Louis Armstrong, along with many other invited guests.

They played the Pete Seeger standard “We Shall Overcome,” and Coleman even sang on the recording. The best cuts were released later that year as Louis Armstrong & His Friends.

Louis passed away just a few months after that session. Following one last set of concerts, the New Orleans legend had a heart attack and died at the age of 69. Jazz music went on, of course, but surely this was the end of an era.

Louis’ unbridled optimism had felt out of place to the younger generation in the early 50s, and even more so by the end of the 60s.

But Louis embodied a big part of jazz’s eternal power, the power of the entire movement.

No matter their place in society or how terrible their personal situation could be, these men and women radiated hope and dignity through their creative collective alchemy.

It’s hard not to feel grateful when looking back at all the talented souls who have graced us with their music.

No matter what else might be transpiring around me, I think to myself:

What a wonderful world.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

“… they got rock musicians to think outside the box in terms of experimentation and improvised playing.”

Yeah, although prog-rock seems to be usually thought of as British rock musicians trying to be taken seriously by incorporating the classical music-tropes, I’m pretty sure they were mostly trying to keep up with “Bitches Brew.”

That sounds right. Maybe Genesis aside.

When I started getting into bebop in college, a number of albums became favorites, A Love Supreme was the first to move me on a spiritual level. Years later, I would have a similar experience with Kind of Blue. To me, bebop is nothing short of a musical miracle.

Kind of Blue was one of the discoveries I made via Columbia House, and needless to say it stands as one of the best CH purchases I ever made.

I was cued into A Love Supreme a little indirectly, via punk esoteria. The DC band Nation of Ulysses has a song called “The Sound of Jazz to Come” (the title a reference to Ornette Coleman) wherein the singer chants “a love supreme” at the beginning and end. So when I saw the Coltrane album I was already intrigued. It didn’t hurt that my friend at the time described it as “jazz as pure rock n roll.” It didn’t disappoint.

Here’s the song:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aBcmGhvZijo

I enjoy jazz, but I am not an expert. I have a lot of the albums you mentioned in your article Phylum (Getz/Gilberto, Kind of Blue, A Love Supreme, In a Silent Way, Bitches Brew), but no rare cuts from any of these artists. I do have one Ornette Coleman album but I had a hard time engaging with it, with a couple of exceptions, most of the songs were too shapeless for me to wrap my head around.

It almost feels cliché, but I still feel like Kind of Blue is just the perfect album. It still feels fresh and alive 100+ spins later. Never wears out its welcome.

I’m not an expert either, although I’ve befriended several jazz heads who have turned me onto tons of sounds and albums. And the two points of maximum overlap of music interest with my wife are classical and jazz. Like you, she has no time for the free jazz stuff.

She does like some of Charles Mingus’ stuff though. As I mentioned, he’s not free jazz, but still pretty avant garde. My favorite album is The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, though that’s a bit too intense for her. She loves earlier albums like Pithecantropus Erectus, The Clown, and Mingus Ah Um.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kqOJ6UI6_3w

I remain a jazz philistine. Reading about its evolution and understanding the protagonists is more entertaining than listening to it.

Maybe one day it’ll click but for now this’ll do nicely.

Even vocal jazz, or just the instrumental stuff?

Have you ever given Kind of Blue a listen? I’d say if you can’t vibe to that, then instrumental jazz really isn’t your thing.

If this is not perfection, then you can call me Goliath.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ylXk1LBvIqU

I think it’s more instrumental jazz that I struggle with. I do recognise So What (parts of it at least, no doubt from film soundtracks) but it just isn’t my vibe.

Although it may be all about finding the right vibe for listening. There’s a 2nd hand bookstore where I grew up, it was a 19th century stone built train station they turned into a shop. I’ve been going to it since I was a teenager, still go in when I’m back visiting family. They always have jazz playing, from the more mellow end of the spectrum, along the lines of So What. In the winter the lack of modern heating and large rooms means it can be freezing in there but they have the period fireplaces with log fires burning and the jazz soundtrack to browsing the books makes total sense.

If I listen purely in that environment I’m onboard.

I hear you. A lot of jazz resonates with me. But some other various types of music that are very popular I could completely leave behind. It’s funny how our brains are wired.

Well, I’d be lying if I said I didn’t take any sort of pleasure knowing that your reaction to the song is, ultimately, “So what?”

Man, I love Bossa Nova and Bebop. Even their names sound cool.

Free Jazz not so much. I get the concept, I like the concept, I just don’t like the result. As they say, it’s a “challenging” listen. Or maybe hard listening as opposed to easy listening.

Nicely put together, Phylum. Looking forward to Part 19.

Definitely hard listening. Made even harder with psychotropic substances.

Sometimes you need a little spiritual terror in your life.

I begged my parents to let me go to my first concert back in 1973. It took three weeks, but I finally got them to say yes, just in time to get tickets for me, Steve, and Vinney.

i was a fan of cheesy top 40, The Beatles, soul music and I was just getting interested in progressive rock. So my girlfriend at the time was very puzzled that I chose to see this artist.

$500 or a green upthumb to whoever can guess the name. They are featured in this article.

ESP?

Lifetime?

John McLaughlin And The Mahavishnu Orchestra!

Amazingly: there is audio!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wkdPQBJqJjM

Wow! Jealous. I love their From Nothingness to Eternity album which may have been from that same tour.

There is just so much jazz out there. I LOVE some of it, and I like a good amount of it. So why, why, why have I never taken the time to finally listen to Kind of Blue or A Love Supreme? I’ve listened to some other weirdness like Bitches Brew (I kinda like it) and Sketches of Spain (was a little disappointed) and Giant Steps (I liked it). But I tend to like music with a bit more form than that freer jazz. I’ve never quite given be-bop and hard-bop the chances they deserve. I’ve always wanted to, since I know how much Walter and Donald of Steely Dan loved those genres.

Vince Guaraldi’s first album of Peanuts material A Boy Named Charlie Brown is one of my all time most played albums, and I’m sure there is a copy of it in heaven. And I really love Bossa Nova related jazz. I certainly love the pop-jazz of the big-band/swing era.

Pop music tends to be overly simple, classical too calculated, opera too pretentious…but jazz in one form or another (and there are many) seems to be the kind of music that is as reliably satisfying as any. Would I call it my FAVORITE genre? Maybe not, but I’m probably less often disappointed with it than other genres.

Definitely give Kind of Blue and A Love Supreme a try. Supreme has its moments of intensity, but there’s always a sense of structure. I’m surprised you kind of like Bitches Brew, as it’s not shy with the noodling and wailing.

Sketches of Spain is striking for how desolate it sounds. Miles’ playing almost always has a touch of melancholy, but that album can be downright bleak. Certainly not the crossover experiment that it seems to be.

The main exception is “Solea,” which is a jam:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AHEzyqhDASw