Fact Check: The revolution was televised.

It was filmed and broadcast into homes throughout the nation.

The revolution was captured in audio, and discussed on the radio. And the revolution was reported in local papers. More frequently with each passing year.

What did Americans think of the revolution unfolding around them? Most were, at best, concerned by what they saw. Many were horrified.

Imagine it’s 1966 and you’re a factory worker in Dayton, Ohio.

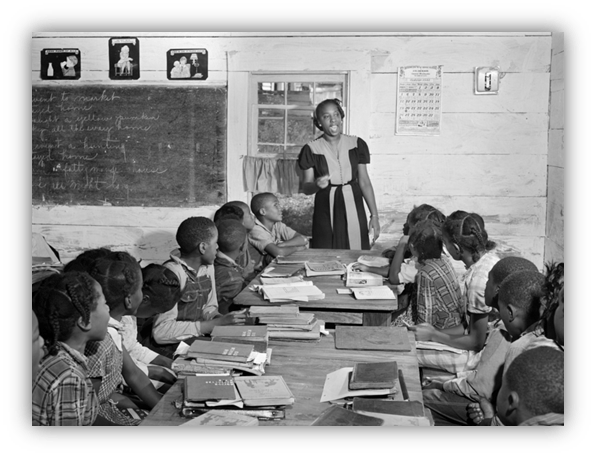

Or an elementary school teacher in Fayetteville, Arkansas.

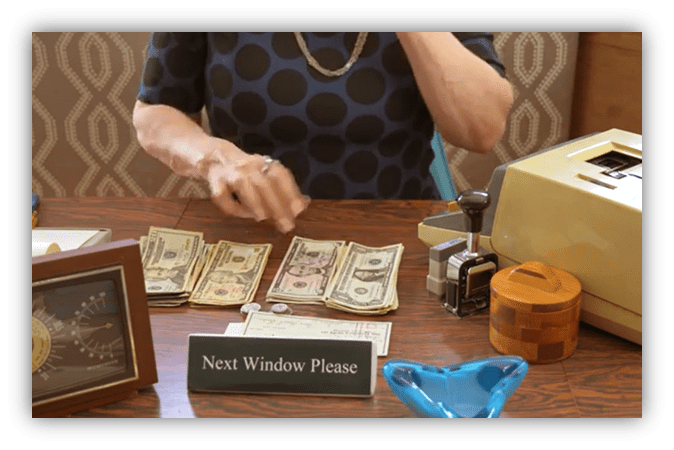

Or a bank teller in the suburbs of Riverside, California.

A few years earlier, you had probably seen news reports about non-violent protests against racial segregation in the South. And that led to major legislation: the Civil Right Act of 1964. But now you see students all across the nation protesting every aspect about the country. Including education itself.

As your TV dinner is warming up, you catch news footage of some kids desecrating American flags. Others carry signs with obscene words.

There are newspaper stories about students burning books. More and more stories about the spread of marijuana on college campuses. And not long after, of LSD.

What had happened to the country? Why did everything suddenly go nuts?

These concerned citizens wanted answers. But more importantly, they wanted solutions. And some key political figures rose to power based on their vows to quell the spreading chaos.

And some key political figures rose to power based on their vows to quell the spreading chaos.

Put To the Test

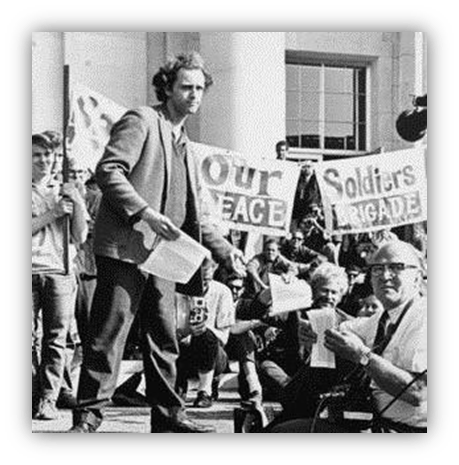

In December, 1964, the Berkeley Free Speech Movement organized a sit-in protest inside Sproul Hall on Berkeley campus.

Over 1,000 students occupied the building and refused to move.

Once the campus closed for the night, the police were called in to address the situation, though they were unsure of how to proceed. Reporters showed up and carried news of the demonstration, which prompted state officials to plead with the governor to resolve the matter.

Governor Pat Brown called in an army of police to the school, and over 800 students were dragged out of the building and arrested. It was a scandal, and it attracted a lot of attention.

Given that UC Berkeley was the very first campus that had erupted into protests, it’s not surprising that the new student movement’s first arch-nemesis rose to political prominence based on the unrest there.

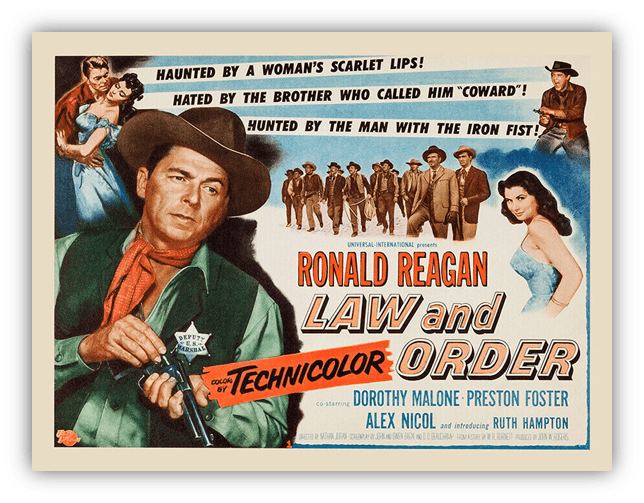

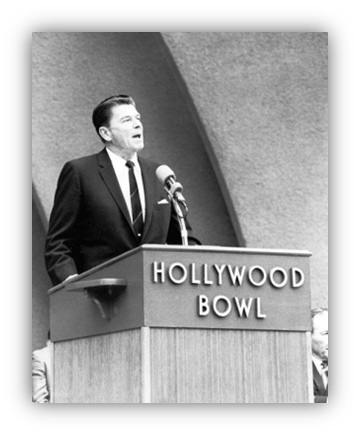

Interestingly, this nemesis came from Hollywood.

Or, rather, he was a former actor. And he wanted to introduce these young punks to a little film he made in 1953 called…Law and Order.

This was Ronald Reagan.

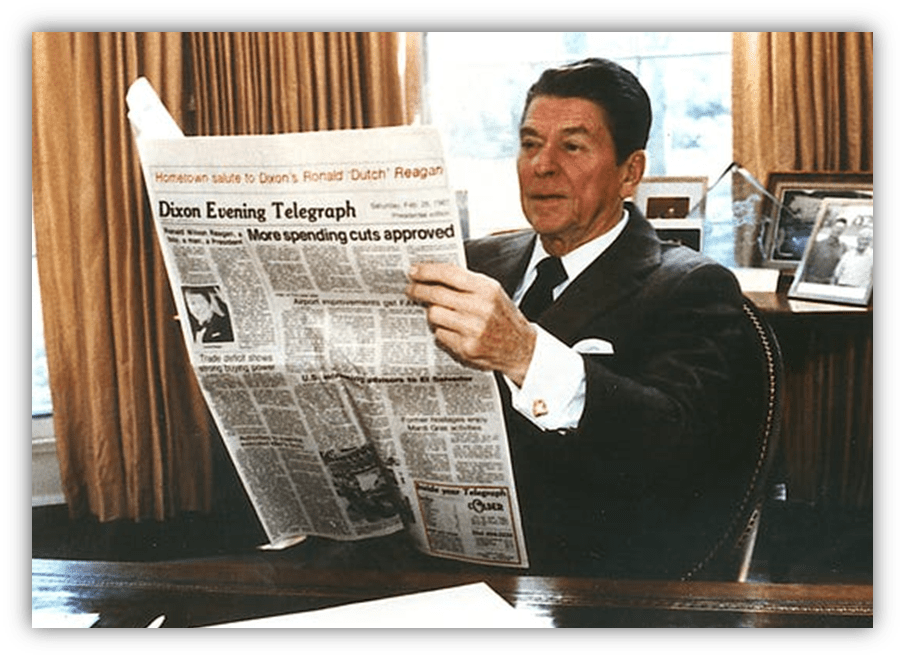

Reagan had been eyeing a political career for some time. After Barry Goldwater had published The Conscience of a Conservative in 1960, Reagan was inspired to fight against the many regulations of federal New Deal policies. But it was the Berkeley protests that gave him a path to power.

In 1966, Reagan rode a wave of popular anger over the protests into the office of the governor.

“We jumped on [student unrest] as an issue,” his PR specialist later recalled. “I think Reagan escalated it into an issue and it started showing up in the polls.”

Regan painted the problem as stemming from poor leadership. California’s governor and its university administration were just too darn liberal, he argued. The students were being coddled, and so they threw tantrums. Someone had to step in and bring order, and that someone was Ronald Reagan.

“This has been allowed to go on in the name of academic freedom. What in heaven’s name does academic freedom have to do with rioting? With anarchy? With attempts to destroy the primary purpose of the University, which is to educate our young people?”

That November, governor Pat Brown was defeated in a landslide.

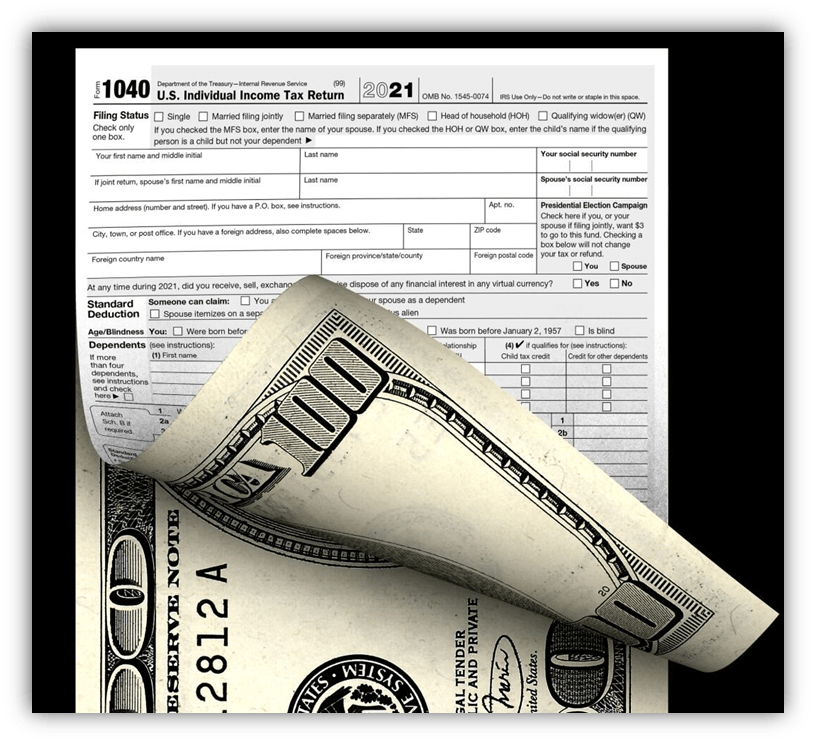

In 1966, California residents paid about $200 per year in fees. When Reagan left office in 1974, the fees had tripled, and they’d go up and up from there.

Soon enough, the new governor set his sights on the crown jewel of Kerr’s legacy: free admission and tuition to all California residents. First he tried to raise tuition outright, proposing that the extra money go to a tax refund. When this attempt failed, Reagan put his focus on student registration fees, steadily increasing them to exorbitant levels.

Reagan’s first move in office was to force a vote to dismiss UC California’s president Clark Kerr.

Once a hero for the New Deal, Kerr had since become a villain for student activists. And suddenly he was an extra tumbling out of sight with a Wilhelm scream.

Soon enough, the new governor set his sights on the crown jewel of Kerr’s legacy: free admission and tuition to all California residents. First he tried to raise tuition outright, proposing that the extra money go to a tax refund. When this attempt failed, Reagan put his focus on student registration fees, steadily increasing them to exorbitant levels.

In 1966, California residents paid about $200 per year in fees. When Reagan left office in 1974, the fees had tripled, and they’d go up and up from there.

Harsh stuff, to be sure. Yet there was a logic behind Reagan’s actions. A logic that his constituents understood perfectly.

For decades, taxpayers poured money into higher education, either directly or via military funds. The original purpose of the effort was to create a skilled national workforce, for defense, research, technology, management, administration, and teaching.

Yet the recipients of those funds eventually rose up against their elders. They rose up against the military. Against capitalism. And everyday culture. And even against school itself.

In other words: the national project of higher education had broken down. Is it surprising that many investors sought to pull the funds? It makes perfect sense. Action, meet reaction.

The Right: -> To Vote

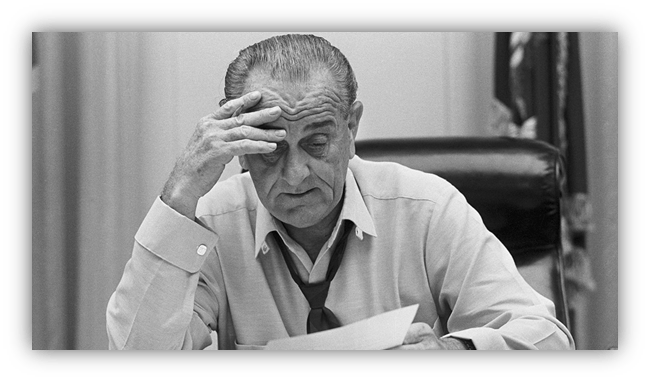

Once Lyndon Johnson increased military operations in Vietnam, students everywhere began to protest the war, and the president himself.

Johnson had won in a landslide in 1964, and was praised by the left for his historic role in securing civil rights for black Americans.

But by 1968, his party had lost faith in him due to his role in the Vietnam War. He was challenged in the Democratic primaries, and ended up dropping out of the race early.

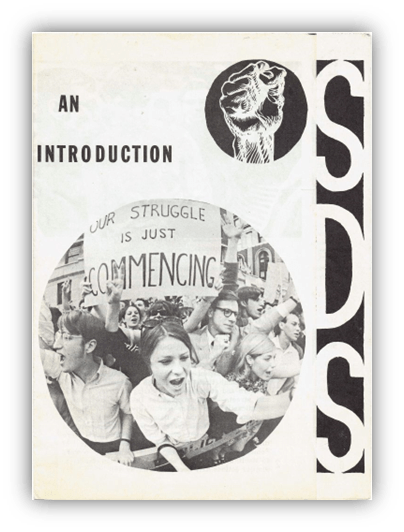

His vice president, Hubert Humphrey, ran in his place. He too was stymied due to his association with the war. The Students for a Democratic Society and other activist groups protested outside the Democratic National Convention that year. The crowds and the police there famously erupted into a riot after a protester attempted to lower an American flag at a park nearby.

The SDS later called for a boycott of the election, encouraging their peers to vote with their feet in solidarity against the warmongers.

Plenty of people did grudgingly vote for Humphrey in the end, but not enough. The election was won by Richard Nixon, the former vice president to Eisenhower. This man sought to escalate operations in Vietnam, saying that force was the best way to end the war. And he did exactly that once in power.

The students’ anger at President Johnson’s foreign policy decisions had been righteous, but suddenly, their worst nightmares had come true. Too late, they would learn that perfect is often the enemy of the good. And passionate ideals die whimpering in the face of cold, implacable strategy.

Like Reagan, Nixon seemed to relish his conflicts with protestors. They provided a useful enemy to rally supporters to his side.

He of course won over white voters from Southern states angry at Johnson’s upending of Jim Crow, but he also got strong support from Northern whites angry at the student anti-war protests.

This second group was mostly blue collar, outraged that these privileged, pampered youths would so flagrantly disrespect their own country. The race and class dimensions of our national cultural war were starting to line up

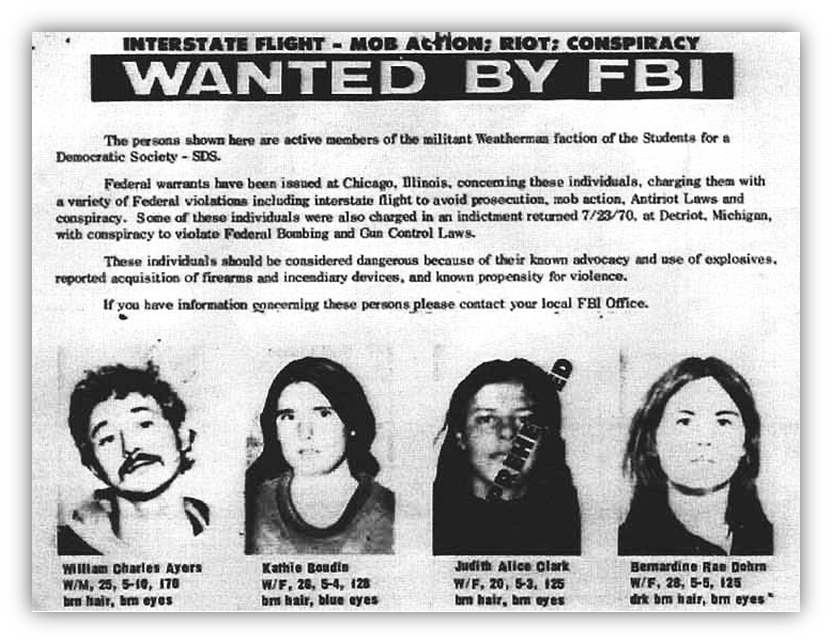

As the war dragged on, and especially once Nixon entered office, student activist groups became more radicalized. The SDS broke into rival factions, divided on whether to use violence to further their agenda.

The Weather Underground was one such faction that advocated violent means for revolutionary ends. The bombing of buildings was thus added to the repertoire of legitimate protest.

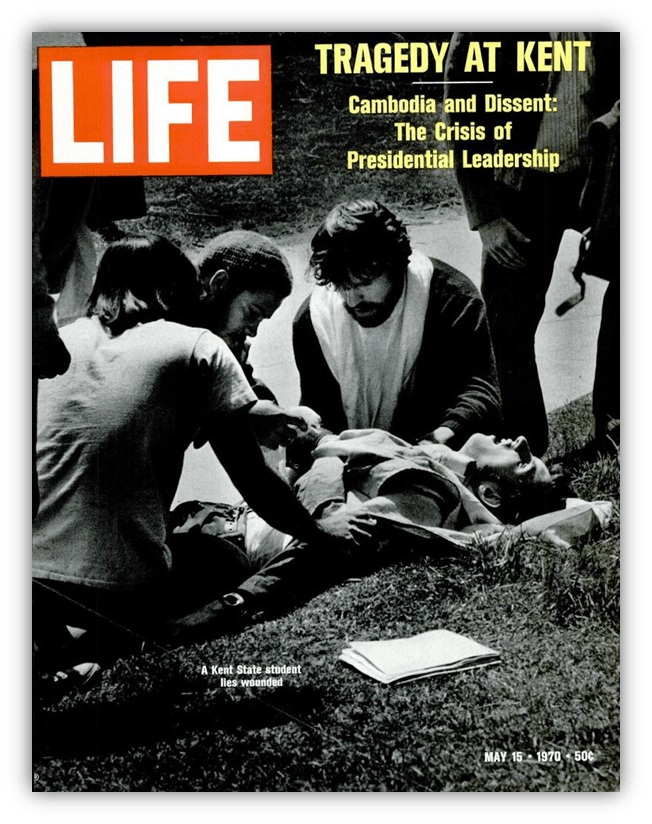

Such mutual ramping up of student and state violence not surprisingly culminated in tragedy. The most infamous of which were the shootings at Kent State University on May 4, 1970.

Like many other demonstrations of this era, back-and-forth altercations with police at the Kent State campus eventually erupted into a violent conflict. Reagan had dealt with such unrest at Berkeley, and was the first governor to call the national guard to a campus protest to bring order. Other governors followed suit for campus unrest in their own states, including Ohio’s Jim Rhodes.

This time, seven student protestors were killed by the guardsmen, and hundreds more were badly wounded.

The Kent State killings galvanized tens of thousands of students across the country into protest, many of those also turning violent.

But despite the appalling legal precedent the Kent State shootings set, most other Americans thought that the fault lie with the protestors, not the guardsmen. The students had lost their minds to radical, subversive causes, and something needed to happen to bring them back in line. Maybe drastic measures were necessary to do so.

And unlike the student protestors, Nixon’s supporters were more than happy to vote with their ballots as well as with their feet. They would continue to do so.

Left In the Dust

As for what measures would actually bring order, most blue-collar voters supported notions like tougher policing. But the business elites had other, grander plans to deal with this New Left revolution.

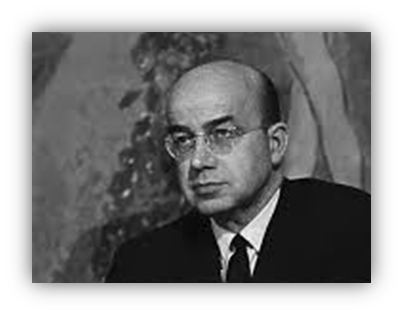

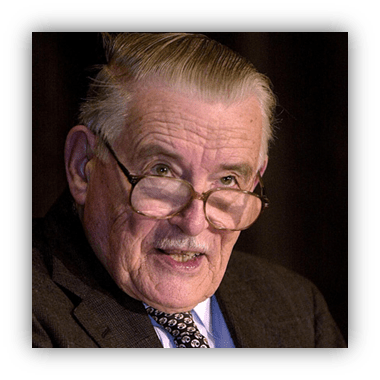

James McGill Buchanan was a respected professor of economics, and he taught at UCLA from 1968 to 1969.

He described the environment there as “a lunatic asylum…a world gone mad.”

Soon after the chairman of the economics department ignored requests by the Black Student Union to hire black faculty members, a makeshift bomb was found in front of the department entrance. Thankfully, the bomb didn’t go off, but such intimidation tactics were beyond the pale to people not well versed in neo-Maoist revolutionary doctrine.

Buchanan was incensed by such rampant radicalization plaguing campus life.

In 1970, he and a colleague would write Academia in Anarchy, a book dedicated to “the Taxpayer.” The authors argued that no more tax dollars be wasted on the public scourge that is higher education.

College is not a public good, they argued, but a “unique industry” to train for certain sectors of the workforce. As such, students should pay the full cost of their tuition, and universities should compete for them. The best students would receive scholarships, while the rest could find some other means. The market forces of the business world would lead the way to a more stable society, free from subsidized radicalism.

Surely Ronald Reagan found some good reading that year.

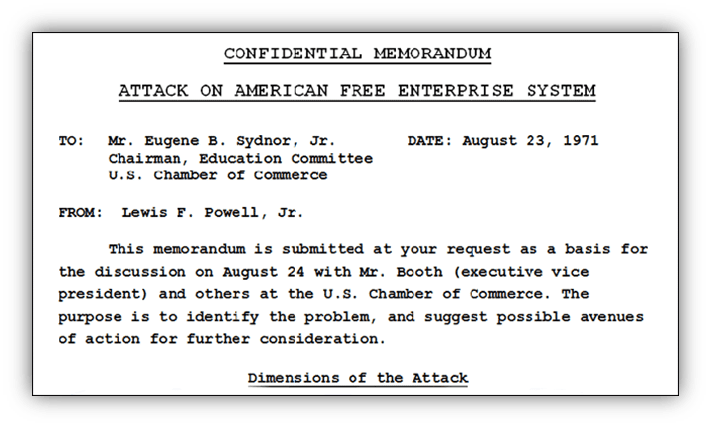

Shortly thereafter, conservative businessmen would greatly broaden the scope of their plan. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce under Nixon tasked lawyer Lewis Powell–soon to become a Supreme Court Justice–to assess what steps were needed to create more robust conditions for free enterprise.

The result was a confidential memorandum titled “Attack on American Free Enterprise System.”

The memo outlined the threat of radical communist and socialist forces in academia, and the appeasement of these forces elsewhere in society.

Revealingly, however, Powell doesn’t name a Maoist revolutionary as the most dangerous threat, but Ralph Nader! It seems the worst sin is proclaiming that corporate leaders who defraud their customers belong in jail.

More importantly, the Powell Memorandum provided recommendations for a conservative counteroffensive, to take the country back from New Deal labor rights groups and New Left activists. And these recommendations served as a blueprint in the years and decades to come.

The recommendations included a ramping up of corporate lobbying to influence political institutions.

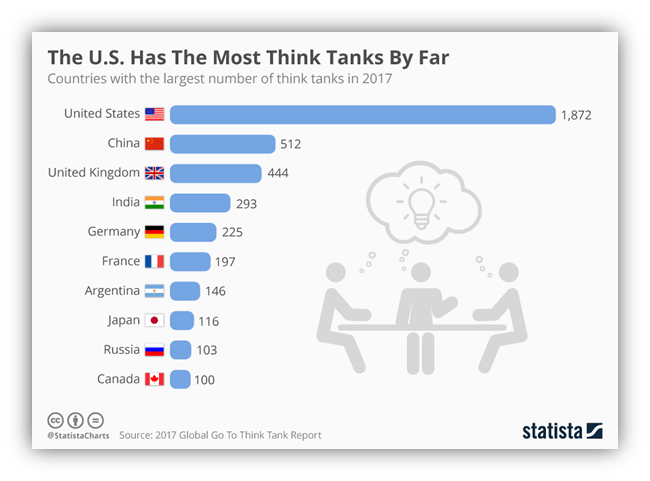

It proposed the creation of business-oriented academic organizations to compete with universities, i.e., think tanks.

It repeatedly called on conservatives to restore “fairness” and “balance” among viewpoints in the culture. Surely, these efforts wouldn’t have any deep impact on our society.

Fuming at the change wrought by the New Left’s Port Huron Statement, the New Right drafted their own revolutionary manifestos. Galvanized by the shock of student radicalization, these conservatives were themselves radicalized.

The difference was that these radicals really knew how to play the long game. This revolution was systemized.

Now, if you’ll excuse me?

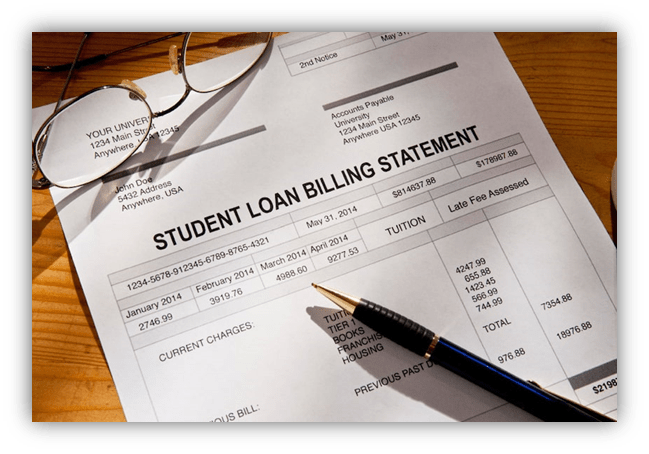

I have to go make a student loan payment…

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

“I have to go make a student loan payment…”

Right on the heels of SL forgiveness being mentioned in the Tuesday Presidential debate.

Time-travelling synchronicity, thy name be Phylum!

A watch stopped on student loan o’ clock sometimes gets it right.

The University of California system is so overloaded with fees (not tuition) that the VA had to change how GI Bill benefits were distributed. GI Bill beneficiaries in California couldn’t get most of their education funded under old GI Bill benefits because it wasn’t tuition, housing or meals — it was thousands of dollars in specious “fees,” which students would still be on the hook for.

The legacy of Reagan cuts deep. From Trickle Down not trickling down, to education bleeding us out. But what made bad even worse were the people who turned Reagan’s austerity into a fundamentalist cult. That’s just unpatriotic, and anti-human.

This is exactly right. The long game usually wins but I think the middle class is finally, FINALLY, catching on.

Let’s hope so!

The withholding of votes in response to the Vietnam war only to let in Nixon who then escalated things highlights the dilemma and possible downfall of fervent idealism.

They’re not wrong to protest but it needs to be carefully weighed up as to what impact it will have. It was apparent in the UK election as some withheld their votes from Labour due to their stance on Israel / Palestine even though it risked leaving the incumbents getting back in even though their position was even worse. I’m sure its something that may well play out in the coming election as well. Are people prepared to compromise on their ideals for the greater good?

Yeah, it’s all about strategy. Tactics are important, but if there’s no strategy, it’s just sound and fury.

I imagine that most black Americans who were able to register in time for the 1968 election did in fact exercise that right. It’s not something to take for granted. It’s a right, and a responsibility.

Weaving the threads together, Phylum. Keep it up!