“When the snows fall and the white winds blow, the lone wolf dies but the pack survives.”

– Ned Stark in ‘A Game of Thrones‘

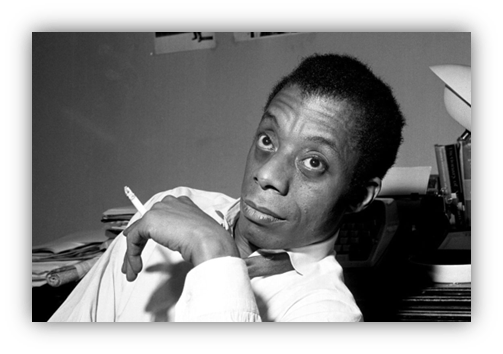

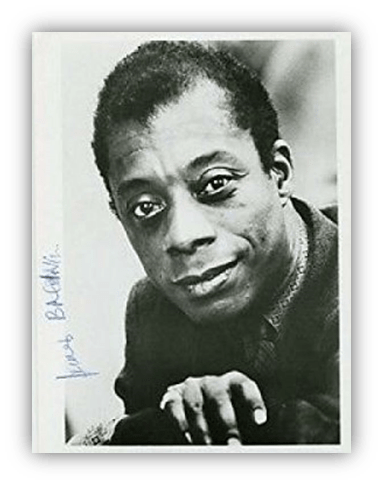

James Baldwin was at his home in Palm Springs when he heard the news that Martin Luther King, Jr. had been shot.

It was April 4, 1968. The writer had been spending time with his friend Billy Dee Williams.

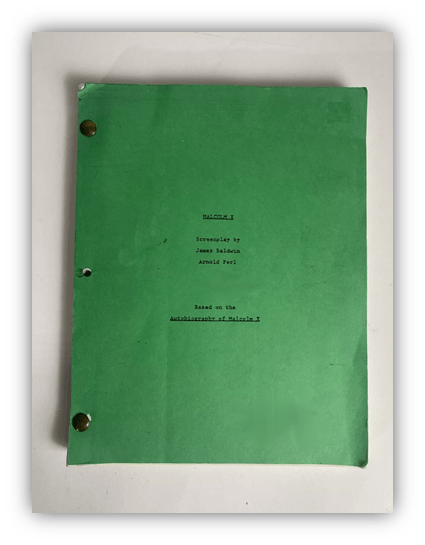

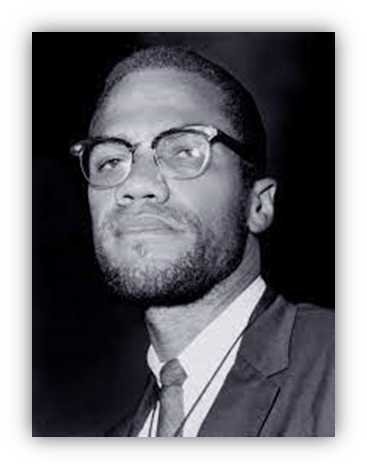

He was hoping to cast Williams for the title role of Malcolm X, a film rendition of the fallen hero’s autobiography that Baldwin was adapting for the screen.

Relaxing by the pool, Baldwin received a phone call, and he was told the news about Martin. It took him a few seconds to comprehend who the caller had meant by “Martin,” but suddenly the realization came to him with dreadful clarity.

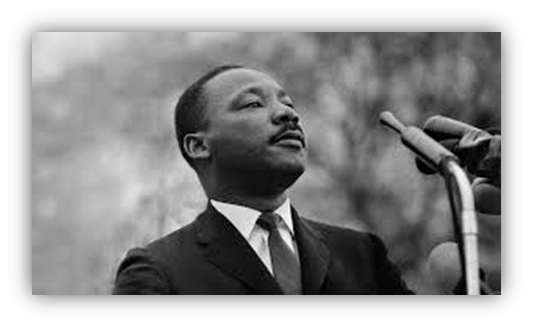

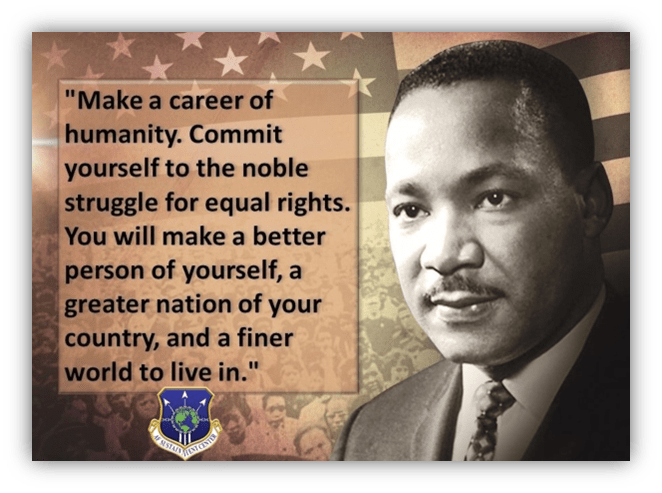

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. His friend, his mentor. A hero for the movement.

Another one shot down.

The man who often seemed like the sole beacon of light in those dark times.

King would die in a hospital an hour after the shooting. His great light was snuffed out.

Everything after that was a blur for Baldwin. “I remember weeping, briefly, more in helpless rage than sorrow, and Billy trying to comfort me. But I really don’t remember that evening at all.”

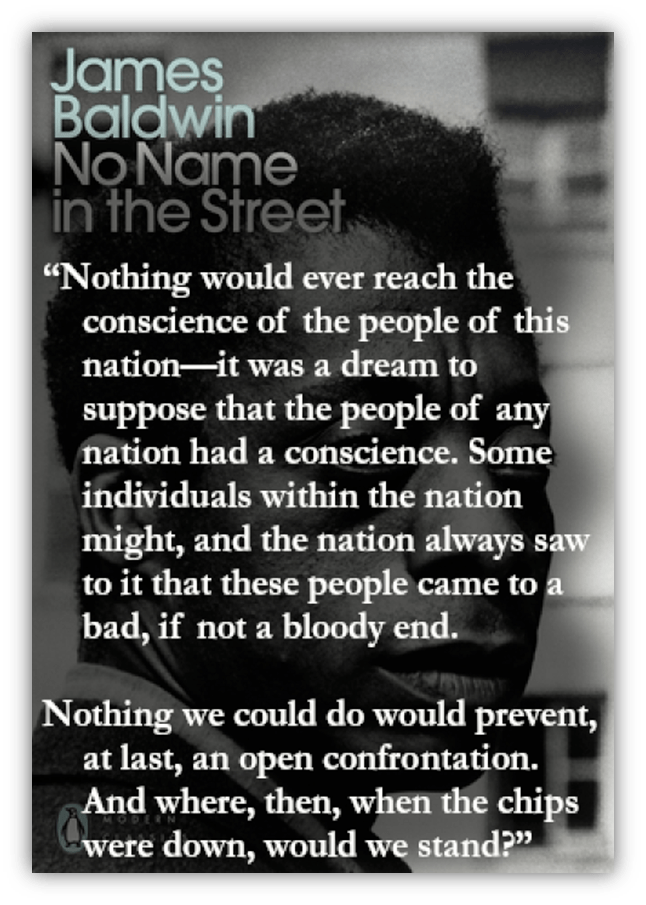

By the time Baldwin had gathered his thoughts on this and related experiences in his book No Name in The Street, his outlook on America’s civil rights struggle had grown noticeably grimmer than in earlier memoirs:

Go Tell It on the Mountain

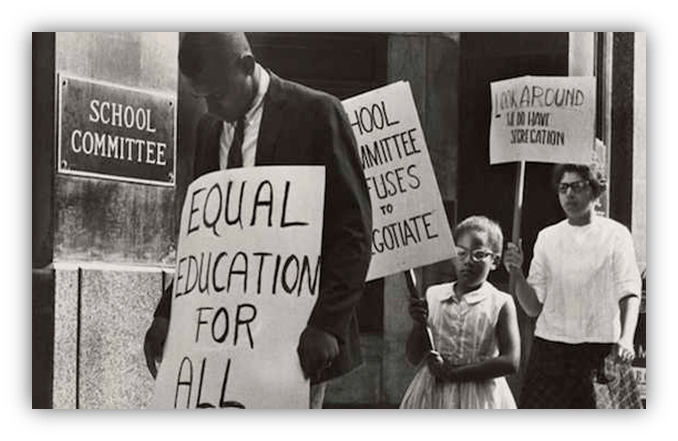

There had been some major wins for black civil rights in America in recent years. Protests in the late 50s and early 60s had led to desegregated buses and schools in several Southern states. And in 1964, equal protection under the law was finally enforced with federal legislation, via the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act.

It was largely thanks to the steadfast coordination of black activist groups across the nation that this legislation was passed.

Crucial among these groups for practical reform were the non-violent protesters such as Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, as well as more established civil rights institutions such as the NAACP.

But other groups played important roles in calling out the oppression of black Americans, often outright resisting the racist status quo of the time.

Most prominent of these groups was the Nation of Islam, with Malcolm X as its most eloquent and forceful spokesperson.

And then there were celebrities of art and entertainment: black writers, actors, and musicians who leveraged their fame for the sake of societal change. Sidney Poitier, Billy Dee Williams, Harry Belafonte, Sammy Davis Jr., and Nina Simone all advocated for civil rights.

James Baldwin was one such celebrity. He was esteemed for his elegant and thoughtful prose.

In novels such as Giovanni’s Room and Another Country, Baldwin revelled in the subtleties and complexities of our world, fearlessly exploring inter-racial relations and queer sexuality.

In his essays and speeches, he detailed the sins of America with the cold contempt of a man subjected to countless indignities for the mere happenstance of his skin color. Yet he would also temper his attacks with some pragmatic hopes for future progress.

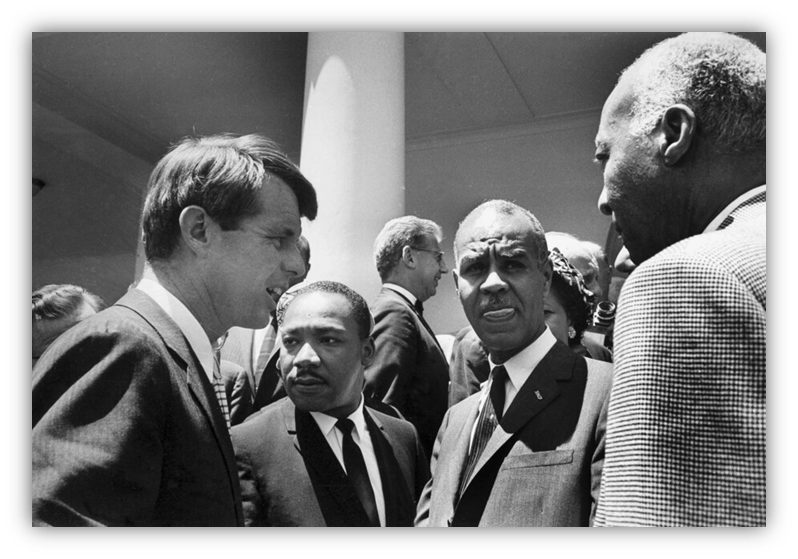

In May of 1963, US Attorney General Robert Kennedy asked Baldwin to help him organize a private, unpublicized get-together to discuss race relations. 1963 was the 100-year anniversary of Lincoln’s emancipation of the slaves. And yet so far, the year had been marked by violence in the wake of protest, particularly the bombings and ensuing riot in Birmingham, Alabama earlier that month.

Hoping to quell the unrest and bring the country together, Bobby Kennedy asked Baldwin to invite a group of black thought leaders to convene in Kennedy’s Manhattan apartment and discuss how to move forward.

But the meeting eventually dissolved into heated disagreement between Kennedy and the others. If anything, it served to highlight the great divide that still existed between the perspectives of white and black Americans, even among the more forward-thinking white leaders.

Still, it was the failure of that meeting that inspired the president of the United States to take action on race relations.

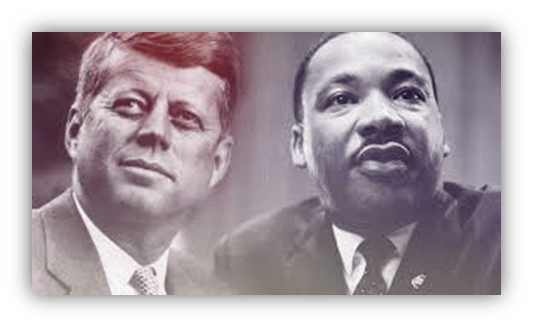

A month later, John F. Kennedy publicly announced his intent to push for federal civil rights legislation.

In retaliation, Klansmen in Mississippi murdered the local NAACP director Medgar Evers in his driveway that same night. Activists across the nation felt more compelled than ever to stand up and be counted for the sake of their own communities.

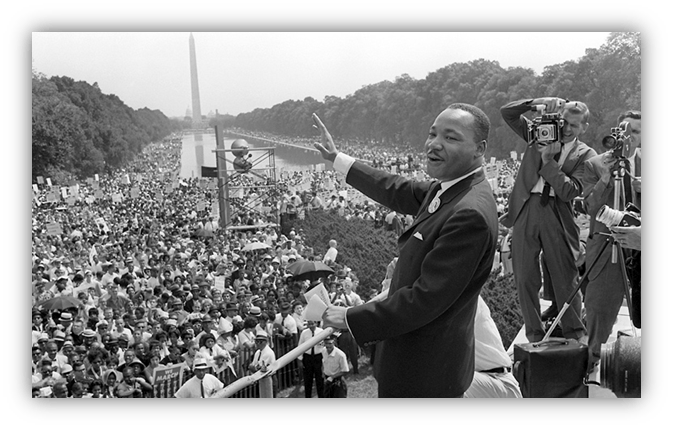

In August of that year, over 250,000 people gathered at the National Mall in Washington, D.C. What had originally been conceived as a sit-in for black employment eventually morphed into a massive March on Washington.

This event culminated with Martin Luther King giving his immortal “I Have a Dream” speech at the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

Hearing Dr. King’s soaring rhetoric, and his dream of a day when this nation would rise up and live out the true meaning of its founding creed, James Baldwin was moved to dream as well.

“That day, for a moment, it almost seemed that we stood on a height, and could see our inheritance; perhaps we could make the kingdom real, perhaps the beloved community would not forever remain that dream one dreamed in agony.”

The Fire Next Time

And yet, the nation saw to it that its individuals of conscience came to a bad, bloody end.

- John F. Kennedy was murdered in November of 1963, while his Civil Rights bill stalled in the House Rules Committee.

- Malcolm X was murdered in early 1965. Robert Kennedy was murdered in June of 1968.

- And Dr. King was murdered in April of that year.

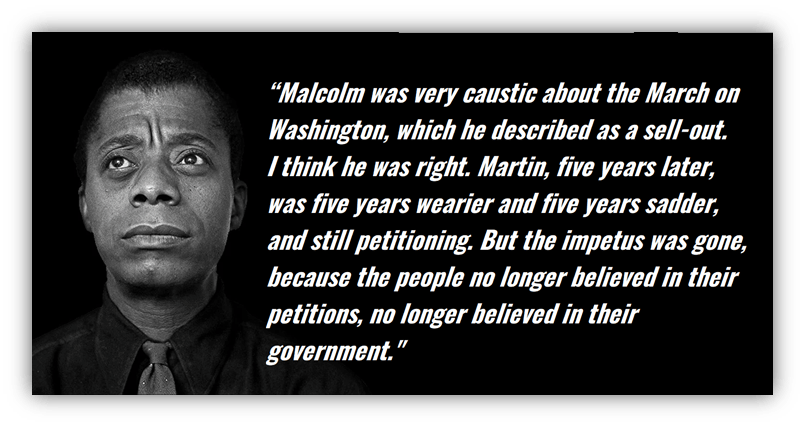

For all his gifts and accomplishments, the King of Love was dead. It was just a few years after a historic civil rights victory, yet it felt like King’s dream of someday reaching equality was dead too. Baldwin mused darkly on the legacy of those earlier years:

“The reasoning behind the march on Washington…was that peaceful assembly would produce the best results. But, five years later, it was very hard to believe that the frontal assault, as planned, on the capitol, could possibly have produced more bloodshed, or more despair. Five years later, it seemed clear that we had merely postponed, and not at all to our advantage, the hour of dreadful reckoning.”

Baldwin came to think that King had been gravely mistaken about the power of nonviolent protest. That violence wasn’t simply justified, it might be necessary. At the very least, it was inevitable. He certainly wasn’t alone there.

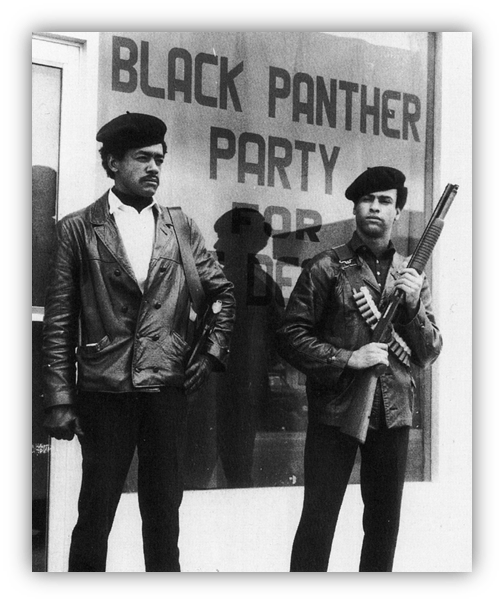

Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam had always believed in being armed. And in 1966, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale founded an organization centered on local efforts to protect black neighborhoods against police aggression.

This was the Black Panther Party for Self Defense.

Local chapters quickly spread across the country. Panther members such as Eldridge Cleaver and Stokely Carmichael soon rose to national prominence by espousing a far more militant vision of black emancipation than Dr. King would have ever supported.

And following King’s assassination, riots erupted across the nation, many of them stemming from conflicts between the police and armed resistors.

The movement was descending into chaos. In the aftermath of the riots, Eldridge Cleaver was charged with attempted murder of police officers, and he fled to Cuba. The next year, the rising star Stokeley Carmichael was accused by his fellow Black Panthers of being a CIA agent, and he fled to Africa.

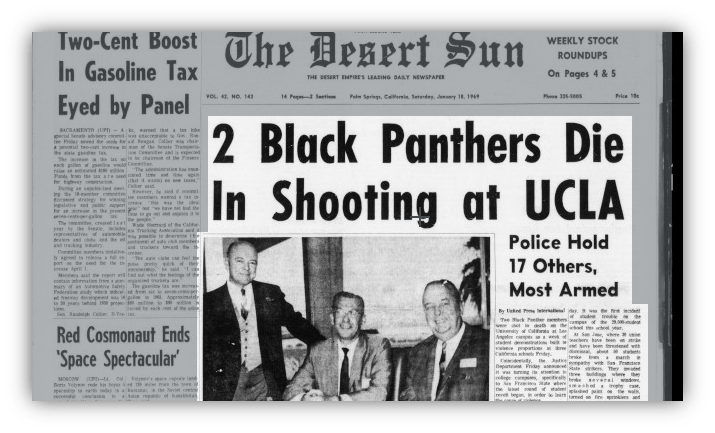

There was even a shootout at a Black Student Union meeting at UCLA, due to a rivalry between Black Panther students versus those with the Nation of Islam. Two of the students were killed as a result.

Animus and paranoia were on the rise, tearing everything apart from within.

And this was all by design.

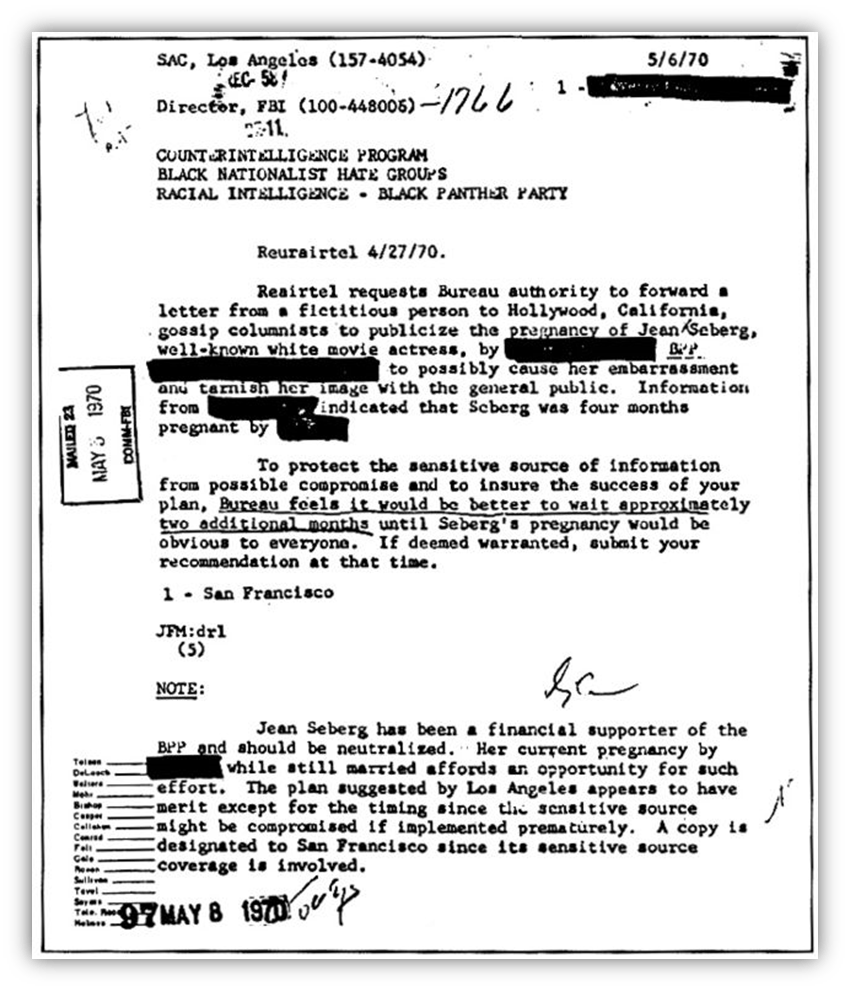

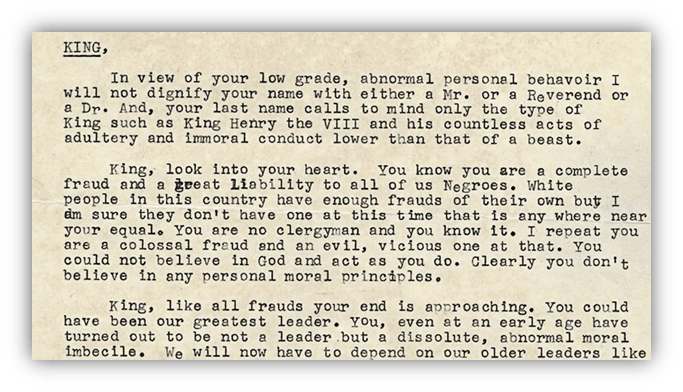

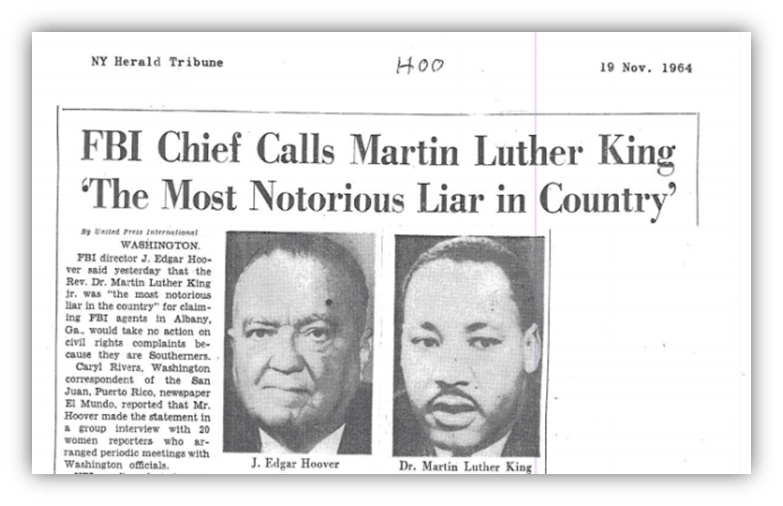

We would later learn that the FBI, under the leadership of J. Edgar Hoover, implemented a secret project of counterintelligence against black activists throughout the 60s and 70s.

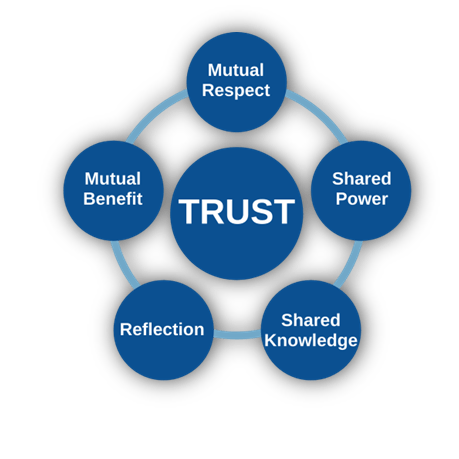

The modus operandi of “COINTELPRO” was to sow discord, mistrust, and aggression among black organizations deemed to be subversive. It literally was a secret plot to destroy the black civil rights movement from within.

The killing of Malcolm X by brothers from the Nation of Islam was almost certainly the direct result of FBI smear campaigns inflaming mutual distrust. Just as with the student shootout at UCLA. Later on, Hoover assumed that Stokely Carmichael had the greatest potential to become the next Malcolm X, and so the FBI engineered a whisper campaign within the Black Panthers to put a target on his back as well.

As for the murders of Martin Luther King and President Kennedy, the circumstances were widely disputed from the start, and many conspiracy theories have swirled around their respective deaths.

The exact details about what happened and why are still not clear, for either victim, to this day. However, one thing that is known now is that King was indeed a target of the FBI’s COINTELPRO operations.

They considered him a radical subversive because of his socialist sympathies, and his friendships with known communists.

According to declassified reports, government agents had repeatedly called King, threatening to publicize details about his sexual infidelity.

The plan was to torment him, in the hope that King would kill himself. As crazy as most conspiracy theories are, one reason they proliferate is because of insane shit like this.

Given the utterly abhorrent facts that we do know, the notion of the FBI pulling off secondhand assassinations via mentally disturbed loners doesn’t even seem like much of a leap either.

All of this is to say that the cynicism of Baldwin and countless other black Americans at that time was perfectly justified.

At the start of the 1970s, King’s dream for America must have seemed hopelessly, foolishly naïve. He had demanded nothing but the best behavior among black Americans to instigate social reform. But the best wasn’t enough. For all his inspiring rhetoric, King’s dream was nothing but a fantasy.

Or was it?

We humans are narrative creatures, and we try to understand the events of our lives and our society in the framing of a story. James Baldwin was a brilliant storyteller, and he was close enough to the manifold tragedies of that era to convey their significance with poignancy and devastating power.

At the same time, he was too close to it all to understand the larger story. If you zoom out and take on a broader timeline, then you can tell a different tale, one that casts the era in a new light. In that story, you can see Dr. King as a father figure.

A Ned Stark, if you will.

Someone who teaches the aspiring young heroes the lessons they will eventually need to succeed. The story takes a dark turn when the father figure dies, and the young heroes flee in fear and despair. It seems for a while that the villain’s cynical theory of the world is correct after all.

That is, until the young heroes themselves learn to step up and live out the vision that their dead mentor had laid out for them. Their plot arc is in fact the main focus of the narrative, and it’s the point in the story where the real transformation comes.

King’s peaceful, pragmatic, and community-minded approach to activism was an absolutely brilliant tool for social change.

That his movement was eventually broken down by the powers that be doesn’t make that any less true.

The cynicism that emerged as a result made perfect sense, as it was a reaction to a tidal wave of tragedy and injustice. Yet now, decades later, we risk paralyzing ourselves in a stupor of cynicism. Either by inaction, or by breaking down our means of collective action, as the FBI originally did via COINTELPRO.

For social reform of all stripes, the time has come for the heroes to embrace King’s message, and to live out his legacy, together.

Don’t take this to mean that we can bank on a happy ending that’s just waiting around the corner.

Our societal story has no real end in sight. And no actions can really be considered heroic without real struggle and real sacrifice.

Substantive change will not come easily. It takes trust, connection, coordination, resolve, pragmatism, patience. And it takes strategy.

Yet, we should take heart as we take action. As King said, “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

Or, to quote James Baldwin in one of his more inspiring moments:

“This is your home, my friend, do not be driven from it; great men have done great things here, and will again, and we can make America what America must become.”

Now, what will our next chapter be?

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

It didn’t really fit within the piece, but still interesting to know: the Malcolm X project Baldwin was working on fizzled out, but decades later Spike Lee took the script and reworked it. Due to the changes, the Baldwin estate requested that his name be removed from the project, which came to be the 1992 Spike Lee Joint Malcolm X.

Baldwin published his version of the script, so I should read it and see what’s different about it. Because, a few strange choices aside (like the extended coda) Lee’s Malcolm X is one of my very favorite films ever. It deftly pulls together a lot of narrative elements, paints a very nuanced picture of the man, and yet it all feels tight, compelling, and moving as a story. As a Hollywood product, it’s borderline miraculous.

The film also hews pretty closely to The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

Insightful as always, Phylum.

At the risk of getting into conspiracy theories, we know that foreign entities are trying to influence the upcoming election. Do you think there’s a domestic effort, too?

Outside the government, like within the MAGA-sphere? Absolutely.

Within the government?

[redacted]

I joke, but I do think the priorities of the FBI have really changed since the Hoover era.

Without excusing past and possible current shadiness, the political establishment of our government actually want its citizens to trust them. I doubt they are prioritizing the sowing of dissension and mistrust as a means to some desired end.

The problem is that others have learned the lesson of COINTELPRO. There’s no erasing what has already transpired. And chaos is a convenient ladder for those so inclined to sow it.

And it’s so easy to do these days.

All you need is one little finger and a computer. 🤓

And a little arrogance.

Pro: Everyone gets to have a voice

Con: Terrible people with harmful and destructive societal agendas get to have a voice.

It almost feels that night now we somehow are giving equal credence to both examples. The 1984 –esque doublespeak is out of control. I meet people every day who can’t tell the difference.

Going forward, how does this scale? Do we have the bandwidth to discern the constructive from the incindiary?

I can’t imagine any improved functioning without some sort of regulation on social media.

Specifically regulating the algorithms designed for maximum engagement and virality via moral outrage. And specifically limiting access to children and teens.

Jonathan Haidt has been championing some of these things in recent years. As has the tech ethicist Tristan Harris:

https://www.humanetech.com/

Maybe some day we can make the internet a brave new world that’s not…Brave New World.

On my down days, I daydream about how I might, in some tiny way contribute to the betterment of the world.

Thank you for letting me know that “tech ethicist” is a thing. A new and encouracging aspriration: unlocked.

#Tethics

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n9cdGXa-uyM

You have already contributed to the betterment of the world for those of us who enjoy this space to examine and discuss serious subjects without rancor. And, of course, to reference Mr. Blobby whenever he can be worked in. Also to reference Mr. Blobby when he has no application at all to the matter at hand.

❤

If you’re hankering to worry about AI as well, this is a good discussion to check out:

https://www.vox.com/the-gray-area/372742/democracy-ai-warning-yuval-noah-harari-nexus

I think there is definitely an effort to affect the election from within the government, especially at the state and local levels. Witness the massive voter purges. And the refusal of Congress to pass the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement bill certainly points to complicity within the federal government as well.

Oh yes, for sure. And also some bad actors within the federal government, such as our current Speaker of the House. But those efforts are more like updated versions of Jim Crow policies. Maybe softer, but no more sensible and no less cynical.

Not much softer. But definitely aimed at making sure that only the “right” people can vote.

Phylum, have you watched the 2010 film Night Catches Us, starring still-fairly-unknown Anthony Mackie and Kerry Washington? Excellent movie, really set in its period — Philadelphia 1976, the vestiges of the decimated Black Panther Party still eking by, grounded in old grievances, the COINTELPRO fingerprints still visible for those who have eyes to see. It’s a great story, but it’s almost magical how it captures the moment — not just the clothes and the cars, but the living scars of people beaten by the system, still getting by.

I’ve never heard of it. Sounds excellent. I’ll have to check it out. Not least because Philly in 1976 is not too far from my own birth and childhood there.

I watched Night Catches Us last night. It really was excellent. It’s very subtle, like a tone poem, inviting contemplation rather than hammering its points into viewers heads. Which, to me, is the best kind of story.

Once again, agents of power prove themselves to be on the wrong side of history in a vain attempt to hold back progress.

Let’s hope that even in the event of setbacks and ongoing attempts to stymie that progress that your final messages of hope are accurate and the arc continues towards justice.

At the very least, let’s hope that our story is not adapted into a series by two cynical hacks who finish the arc with total nonsense.