October 18, 1940. New York City:

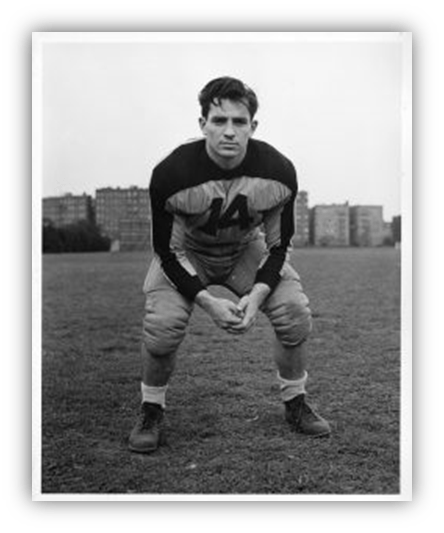

Columbia University’s football team, the Lions, played against the Gray Bees of St. Benedict’s Preparatory School.

On this day, coach Lou Little decided to give his new running back another chance off the bench. He had his doubts about Jack, but since he’d played well enough the last game, Lou figured he’d see what the kid could do.

It did not go well. Jack was injured early on, and had to sit out the rest of the game due to the pain of his ankle. And he couldn’t play any subsequent games either.

With that one tumble, the kid’s dreams of being a professional athlete went down the drain.

Fortunately, he had his writing to fall back on. No longer preoccupied with football and his circle of jocks, Jack began to befriend some more sensitive types he met in his Columbia dormitory.

His new best buds were Lucien Carr and Allen Ginsberg, also aspiring writers.

They would read each other’s work, offering feedback and encouragement. Little did they know at the time, their creative coterie would come to change the world.

This was the group that came to call themselves the Beat Generation.

“Beat” as in: beaten down by society. “Beat” as in: beatitudes. “Beat” as in: move your body to the beat. This was a new Bohemian movement, a small band of outsiders who would come to typify what it meant to be a creative free spirit for generations to come.

Walking through the influences of the Beats is almost like a tour through my previous posts on art.

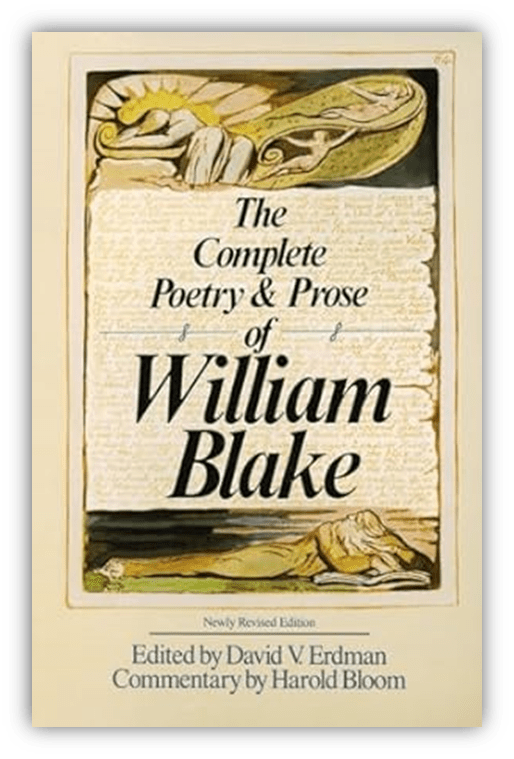

They of course loved the European Romantics, and especially William Blake.

They revered the American Transcendentalists, and worshipped Walt Whitman.

They pulled from the artful decadence of Baudelaire and Rimbaud, and James’ Joyce’s full-on stream of consciousness.

They borrowed from Dada, and even more so from Surrealism.

They were friends with the Abstract Expressionists. They brought in Eastern mysticism like Henry Cowell and John Cage.

And they attended the early bebop shows, dreaming they might some day work words as freely as Charlie Parker blew notes.

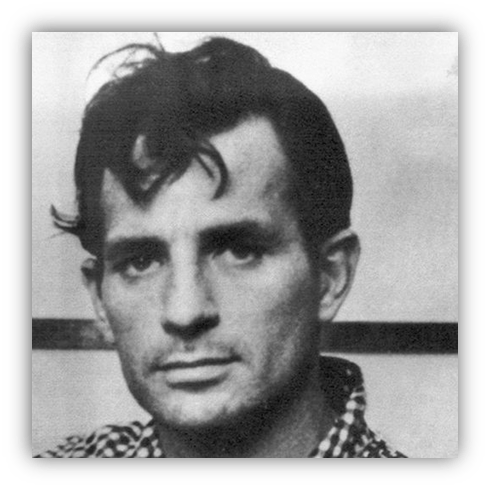

While hundreds of artists were in some way part of the Beat movement, the three most impactful artists were Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and an older man they met through a mutual friend: William Burroughs.

Kerouac was the first to find fame on a national scale. Given his blue collar background and his Catholic faith, it makes sense that he was the weirdo deemed most relatable by the larger populace.

He was a handsome man, a sports fan, no stranger to the ladies, yet he felt estranged from society, alienated.

Of course, it took some time for his writing to be appreciated. He wrote his first novel in 1942, but took another eight years for one of his works to be published. And The Town and the City didn’t garner much attention. It was only after On the Road was published in 1957 did he see any success.

By that time, the public had already been primed for alienation by Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye. They had been primed for nonconformity by James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, and the libidinal release of the rock n roll bad boys. Towards the end of the 50s, there was a sizable audience ready to receive Kerouac’s Romantic outsider vision.

His freely flowing prose would come to speak to many others who felt the same emptiness with the daily grind, with shallow amusements everywhere.

He struck a chord with those who were searching for something more. Something real. Something authentic.

“And for just a moment I had reached the point of ecstasy that I always wanted to reach,

which was the complete step across chronological time into timeless shadows, and wonderment in the bleakness of the mortal realm,

and the sensation of death kicking at my heels to move on, with phantom dogging its own heels, and myself hurrying to a plank where all the angels dove off and flew into the holy void of un-created emptiness,

the potent and inconceivable radiancies shining in bright Mind Essence, innumerable lotus-lands falling open in the magic mothswarm of heaven.”

Jack Kerouac – “On The Road” – 1957

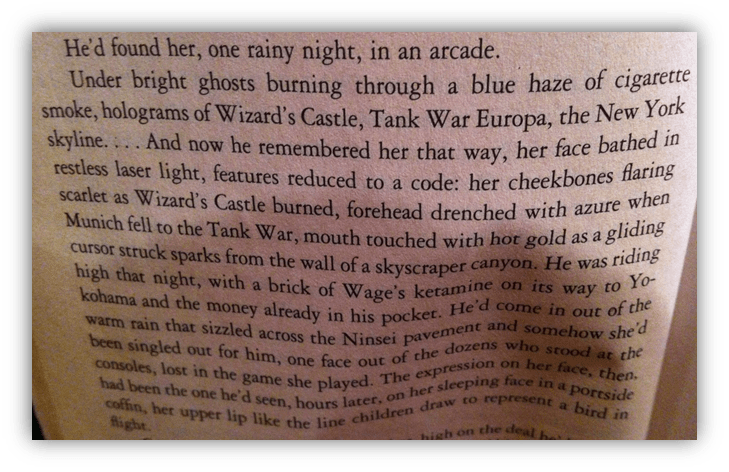

In contrast to Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg was not a relatable character in the 1940s and 50s.

He was shy, soft spoken, Jewish, leftist, and queer. Jack was on the inside looking out, while Allen was on the outside looking out.

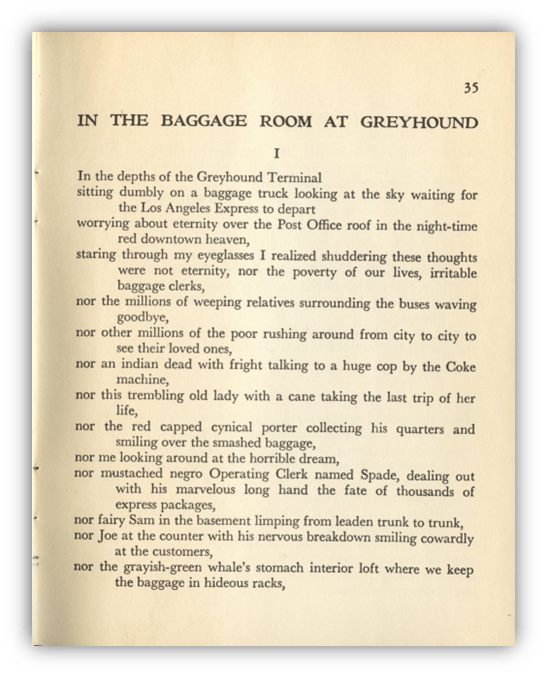

Like with Kerouac, Ginsberg’s writing was about finding and expressing his authentic self. He said that by writing his best poems he was “storing up treasures in heaven.” His poems continue the grand prophetic tradition of William Blake and Walt Whitman: by turns rhapsodic, erotic, patriotic, and elegiac.

His most famous work, Howl, describes the creativity of his fellow artists stemming directly from their struggle to live in the world around them. Their genius working hand in hand with their slow self-destruction.

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix, angel-headed hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night, who poverty and tatters and hollow-eyed and high sat up smoking in the supernatural darkness of cold-water flats floating across the tops of cities contemplating jazz,

who bared their brains to Heaven under the El and saw Mohammedan angels staggering on tenement roofs illuminated, who passed through universities with radiant cool eyes hallucinating Arkansas and Blake-light tragedy among the scholars of war, who were expelled from the academies for crazy & publishing obscene odes on the windows of the skull, who cowered in unshaven rooms in underwear, burning their money in wastebaskets and listening to the Terror through the wall…”

Allen Ginsberg – “Howl” – 1956

There was indeed a fair amount of self-destructive behavior among the Beats.

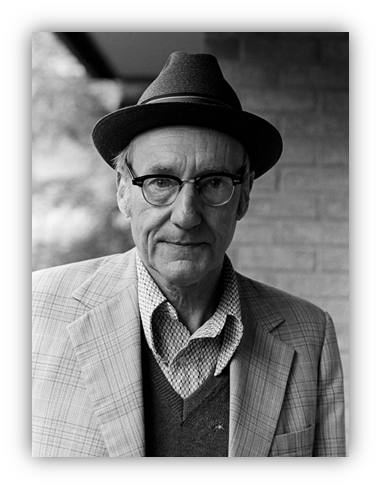

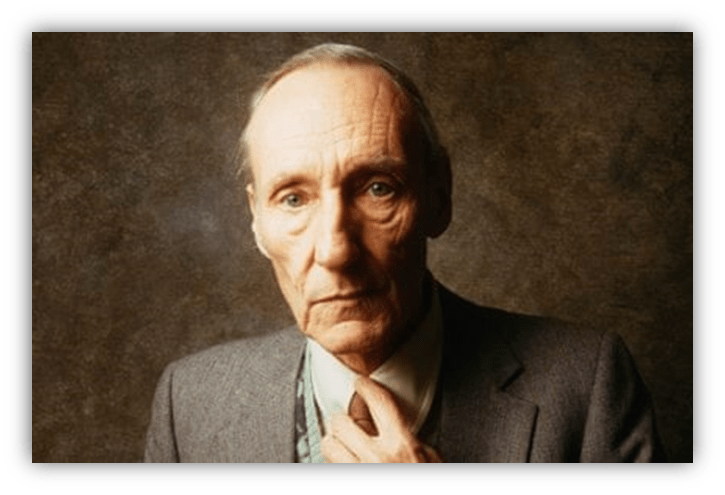

And no one personifies the compulsive numbing of one’s mind from the horrors of the world better than William Burroughs.

Burroughs was almost 30 when he first met Kerouac and Ginsberg, and was already a few years into a heroin addiction.

Upon reading some letters written by Burroughs, Ginsberg encouraged his friend to write something more substantial. Burroughs wrote a sardonic but straight-forward novel about heroin addiction. Junkie was published in 1953, under the pseudonym William Lee. Like Ginsberg, Burroughs too was queer, and his queerness was the topic of his second novel, though that would not be published until the 1980s

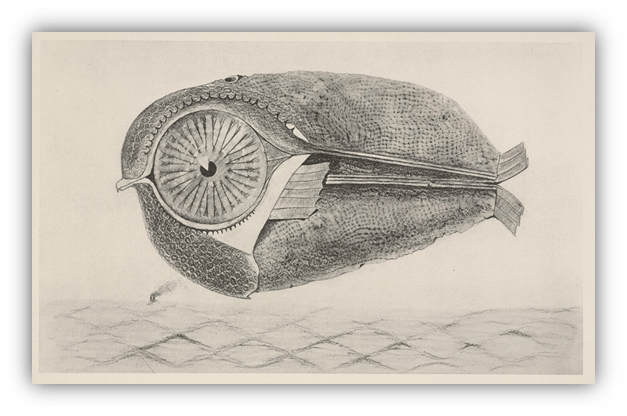

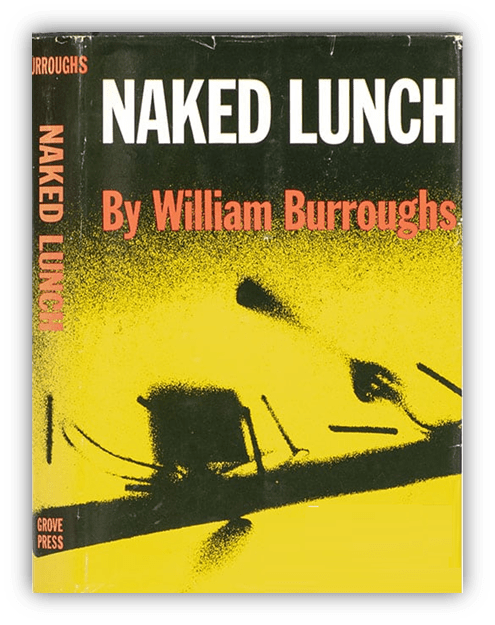

His real legacy would begin with his third novel, the first published under his birth name: the surreal postmodern nightmare that is Naked Lunch.

Partly inspired by his time in the Tangier International Zone, a time spent soaking up drugs and easy sex, the novel ultimately serves as a hallucinogenic journey into the dark heart of the modern culture machine.

Even calling it a “novel” feels like a stretch. There is no discernible plot to be found, just waves of characters and schemes that are some mix of hilarious, absurd, sad, and horrifying. The prose is all the more fragmentary thanks to Burroughs’ method of literally cutting up text and reassembling it to create new combinations, revealing new meaning.

The Dadaists pioneered collages of photos and cut-up poems, but this was a book-length narrative collage.

The scrambling of his prose provided the perfect way for Burroughs to realize his concept of writing as a magical rite: as a vision quest.

“That’s the sex that passes the censor, squeezes through between bureaus, because there’s a space between. In popular songs and Grade B movies, giving away the basic American rottenness, spurting out like breaking boils, throwing out globs of that un-D.T. to fall anywhere and grow into some degenerate cancerous life-form, reproducing a hideous random image.”

William Burroughs – Naked Lunch, 1959

The title of the book came from Kerouac, who said that the work put in plain view what was being pumped into American brains every day:

“a frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork.”

Burroughs’ easy sarcasm and love of Hollywood pastiche indeed made for great satire, with prose that can veer from silly to seering in just a few lines. But the cynicism, horror, and comedic distance of his writing also reflect Burrough’s own troubled state of mind, his own self loathing.

In a sense, he’s baring himself for the world to see, serving as evidence of society’s failures. As if proclaiming: “Look at what a confused wretch this world has created!” It’s a point so incisive it hurts. No amount of horror schlock or sarcasm can cover up the thoughtfulness of his critique.

Amazingly, given his lifestyle, Burroughs lived to the ripe age of 83. Ginsberg died just a few months before him, at the age of 70.

As for Kerouac, he died in 1969 of internal hemorrhages and a damaged liver, brought on by years of alcohol abuse. Like his hero Charlie Parker, his thirst for authentic expression took him to great heights, and a tragic early death.

All of them live on through their legacies.

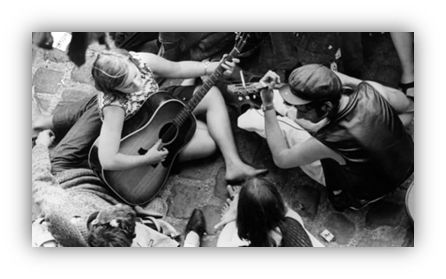

What started as a small clique of self-styled weirdos became an aspiration and template for free spirits all around the world.

By the time of Kerouac’s death, young dreamers everywhere were breaking free from the strictures of mainstream society, and were basically living the lives of the Beats from a generation before.

To the horror of older, more conservative communities, of course.

The Beats were some of the first outsiders-turned-global sensations, but as such they also served as sideshow freaks for those who didn’t understand them.

They were mocked as “Beatniks,” which played on the Soviet Sputnik, and branded the new Bohemians as communists drifting out in space.

This was the start of a toxic back-and-forth that to some extent still exists today, one element of our current culture war.

The freedom the Beats offered was not always for the good of larger society. They tended to dismiss traditions and community. And a lot of the freedom they insisted on seemed to elide responsibility. But they did take responsibility for their own lives.

Their dogged pursuit of authentic living helped later generations understand the importance of honesty and self actualization for a fulfilling life.

Not to mention, through their influence, audiences became interested more generally in the views of those on the margins: blacks, queers, libertines, addicts, Eastern mystics, and just plain eccentrics. With greater understanding eventually came wider acceptance. That was certainly better for society.

Personally, more than any other art movement that came before them, the Beats inspire people like me to make something myself, to get creative on my own terms.

Regardless of what’s considered great or garbage by the rest of the world, I am moved to write something. To create and refine my art, to find a voice that best reflects my authentic self.

What better way to spend our limited time here on earth than to store up treasures in heaven?

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

I appreciate this summary. It’s funny, for as traditional and relatively “buttoned-down” as I always have been, I had a good friend in high school that was bohemian as anyone that I had known. He was a smarty pants (salutatorian of our class of 700), and a musician, but was purposefully scruffy and bizarre. He would throw around the names of these beat authors regularly. I’ve never really gotten into them, so the way they fit into our culture has always escaped me. I know more today than I did.

I’ve lost track of my friend. Last I interacted with him he had showed up on my college campus and wanted to visit, but on the phone he was clearly drunk and I was about to go on a date with my fiancee, so I turned him away. I would make the same choice again, but I haven’t heard from him since. And, since his name is the same as a famous sports figure, he is completely un-googleable. I hope someday that I find him again. He was terribly interesting and fun.

As much as I’ve come to hate what Facebook has become, I will always be grateful for how it allowed me to connect with an estranged friend: a local skinhead girl I hung out with in my high school years. She had a unique name, but it turns out that she had gotten married, so she had a surname that I didn’t know. But years later, out of nowhere, she found me on Facebook, and we were able to reconnect. It’s not impossible, though the challenge of ungoogleable names is a mighty one.

Here’s hoping you can reconnect some time!

Wow, I can’t believe you managed to find the team roster for Columbia’s game that day, mt. Great sleuthing! The internet truly is a land of the weird.

That intro is probably the most I have ever written (and will ever write) about sports. I feel like I deserve an award or something…

I recognize the Beats’ contribution to our culture. It’s huge and respectable, though they’d probably hate to hear that word. I’m sorry to say I haven’t read much of their work. “Howl” left me confused. Even as my eyes scanned the words, my mind was sent elsewhere. I’d have to retrieve it and start the paragraph again. I’m not sure that’s what Ginsberg hoped to achieve.

They’re rugged individuals on the intellectual frontier. Americans love rugged individuals but is scared by intellectuals, which is a perplexing outlook. Thinking is hard (for some of us) but I don’t think that can explain America’s anti-intellectual bent. Can anyone explain this for me?

I know it’s reductive, but I think of America’s illiberal/anti-intellectual vs liberal/intellectual divide as stemming from the historical tension between the nation’s Puritan roots and the early Enlightenment experiments that were mostly derived from Quakerism.

And deeper than that, the divide is between two distinct Christian approaches to community: one based on Jesus in Mark (he who is not against me is with me) versus the Jesus of Matthew (he who is not with me is against me).

But for recent history, the Beats were hugely important in stoking both intellectual curiosity and anti-intellectual jeering.

Still, free verse is not for everyone, and it’s not immediately accessible, often on purpose. I think anyone who has partaken in psychotropic substances at some point in their lives can probably get their mind in a flow sufficient to appreciate Ginsberg’s lyrical streams of consciousness to some extent, with some effort. But part of the key is just going with the flow, looking for possible associations, transitions, puns, and straight up fragments of thought; they’re not nearly as intricate or as ornate as older poems were.

For all their love of bebop, they were much closer to later free jazz.

Thanks, this is as good an explanation as I’ve heard. Reductive, maybe, but sometimes that’s how you get to the crux.

Puritanism, Jonathan Edwards, all that stuff. Religious zealots hate thinking.

Those pesky Puritans!

Whew, out of my depth. I’m too standard issue to be completely comfortable to follow the paths the Beats generated. I may, however be storing treasures in purgatory (or wherever).

I had never considered it, but after reading this it’s obvious that Paul Simon was heavily under the influence of the Beats during the 60s. Sounds of Silence comes particularly to mind.

I have to admit that anything to do with drugs makes me extremely uncomfortable. I don’t even like watching movies where drug use is depicted and especially not when it is glorified. Outside of caffeine, I’ve never taken any sort of mood/perception altering drug, smoked anything (ever), nor even been drunk. I may be missing out, and am boring as day-old oatmeal, but I just cannot go there. (What? TMI? Sorry.)

I would not be surprised at all to learn that Paul Simon was inspired by Allen Ginsberg. You’re right, “The Sound of Silence” has a similarly cryptic, mythopoeic style, like a modern apocalyptic vision.

I might argue that no one has singlehandedly contributed to the romanticization of heroin addiction more than William Burroughs, so great was the impact of his work on the minds of later youths and creatives. But like Hunter S. Thompson, he was by no means offering emphatic endorsements. His depiction of addiction was more complicated and ambivalent than he’s often given credit for.

Thankfully, you don’t need drugs to get to a transcendent plane. They are jet fuel for such a trip, to be sure. But art, music, meditation, and other rituals can take you there as well. Ravi Shankar, sick of playing to kids blissing in the dirt like cats on catnip, tried to impart that notion to the hippies of the 60s, to no avail, but he was right. I’m sure you’ve had at least a few of those types of experiences in the various concerts you’ve been to.

Read On The Road in high school, it seemed like a rite of passage book in the same way as The Catcher In The Rye. The fact it was highlighting a world far removed from early 90s England made it seem ever more intriguing and counter cultural. Haven’t read any Ginsberg or Burroughs, I did watch the film of Naked Lunch but a long time ago so all I can remember is Peter Weller talking to a giant bug. Sounds like an achievement just to make a film out of the source material.

I really like the Naked Lunch film! It actually makes more sense than the book, because Cronenberg ties the narrative elements to Burrough’s own biography.

In that sense, it’s not so faithful to the spirit of its source, but it’s great in its own way, and a tremendous achievement as a coherent adaptation of such a challenging work.

So, I’m going to take another crack at On the Road. I remember being bored. And that left me feeling perturbed. It’s a great American classic and I’m bored. That’s my problem. Not Jack Kerouac’s problem.

Josh Radnor’s Liberal Arts is a pretty decent independent film from 2012. The protagonist is a guidance counselor in his early-thirties who returns to his alma mater. He is smitten with an undergraduate. The filmmaker wisely chooses to make it a platonic relationship. She owns a copy of Twilight. He’s horrified. In the film’s funniest bit, she challenges him to read it. And he does. He hates it. He makes the argument that you don’t read for fun, you read what challenges you. She’s not done matriculating, so he probably has a point. There’s plenty of time to read Twilight, after you graduate. He thanks his father, a college professor, for making him read books he hated.

The literature snob’s demagoguery is even funnier because Elisabeth Reasner, a supporting character, starred in the Twilight series.

That would be a good list:

Top 10 books that stare at you from your shelf like a disappointed parent.

War and Peace would be at the top of my list. As would Gravity’s Rainbow.

Fantastic article, sir.