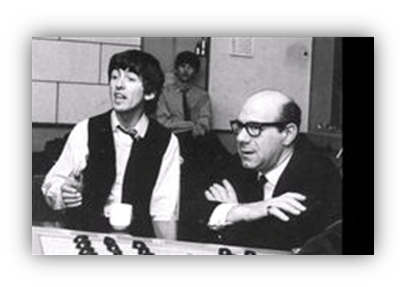

An unsung studio wizard who helped launch two of the biggest bands in history

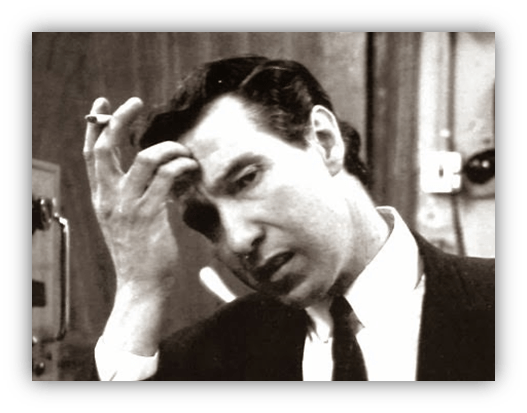

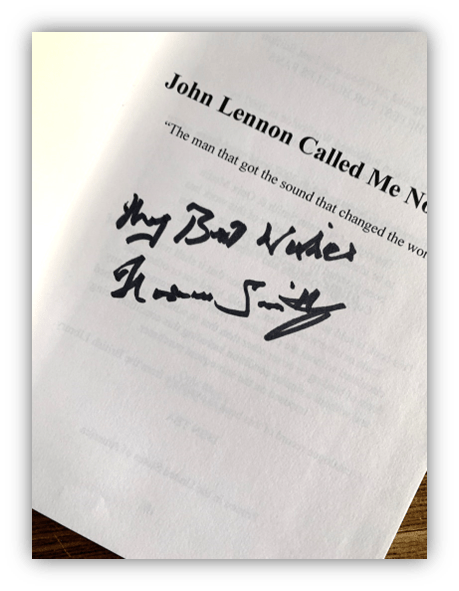

He titled his autobiography, “John Lennon Called Me Normal.”

And that’s true.

The Beatles sometimes made fun of the staid lab coat wearing technicians at EMI, but they liked Norman Smith and his quiet professionalism.

His calm, steady, and unflappable demeanor helped people stay grounded around EMI Recording Studios, where egos, creativity, and experimentation sometimes went overboard.

George Martin praised his expertise and quiet competence, noting that he could be counted on to solve technical problems without fuss or drama.

So, “Normal,” it was.

Born in 1923 and raised in a working-class and musical family, Norman Smith showed early interest in music and electronics, but his path to the music industry wasn’t a straight one.

He first trained as a Royal Air Force glider pilot during World War II, but the war ended before he flew any missions. Still, that training taught him discipline and gave him an appreciation of technical proficiency.

He brought it with him in his later career in the recording studio.

After the war, Smith aspired to be a professional Jazz musician, playing drums in various bands while also working odd jobs to support himself. He could also play piano, trumpet, trombone, vibraphone, and upright bass.

In 1959, Smith saw an ad for sound engineers at EMI Studios.

The ad specified that applicants should be under 28 years old since the open positions were apprenticeships. Smith subtracted seven years from his age.

In the interview, he called rising star Cliff Richard “nauseating.”

That might have been a mistake, but the interviewers thought the same thing.

He quickly progressed from an apprentice to a tape operator to an engineer as he gained experience by assisting on various recording sessions. He was mostly in the background and often uncredited.

But it’s likely he worked with frequent EMI artists like Shirley Bassey, Helen Shapiro, Adam Faith…

…and the “nauseating” Cliff Richard and The Shadows.

He particularly liked The Temperance Seven.

They were a novelty Jazz band who had a #1 hit in 1961 with “You’re Driving Me Crazy.”

They were on the Parlophone label with George Martin producing. Smith later cited their 1930s style as an influence on his own music.

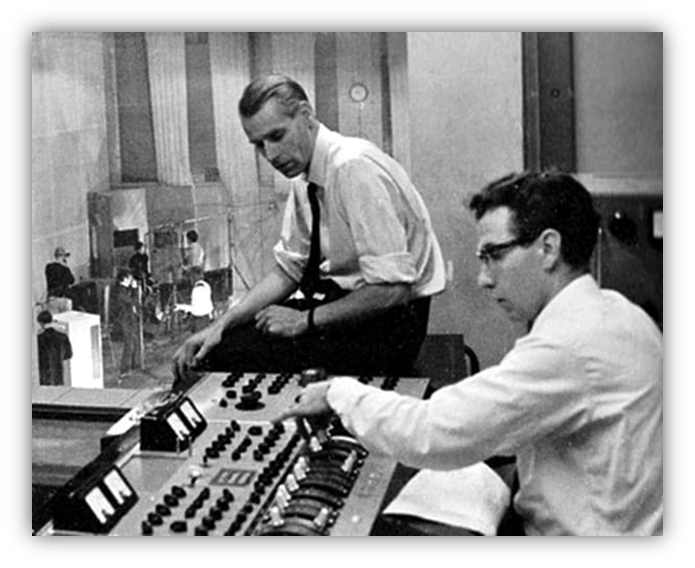

He worked with Martin often. So June 6, 1962 was just another day in the office.

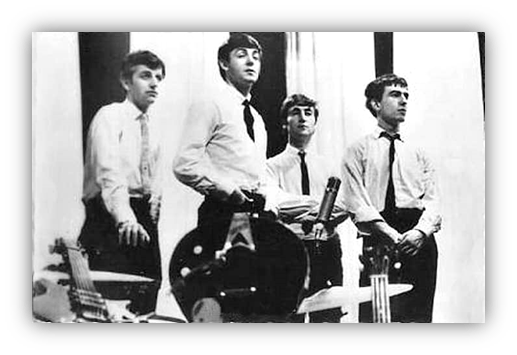

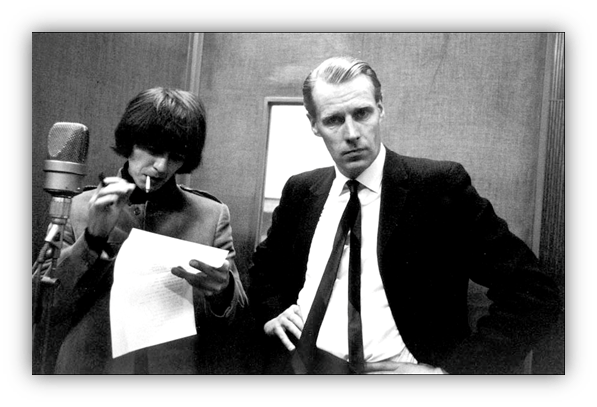

The artists that day were four young Liverpudlians calling themselves The Beatles. His first thought was that he “couldn’t believe what louts they looked with their funny haircuts,” but he took an immediate liking to them.

It could have been any other EMI engineer but luck put Smith in the control booth.

The day was a test session to gauge the band’s potential for a recording contract.

Pete Best was still their drummer. Martin wasn’t in the studio for the first part of the session, but after they recorded “Love Me Do,” Smith sent the tape operator to fetch him from the canteen.

He thought The Beatles might just be something special.

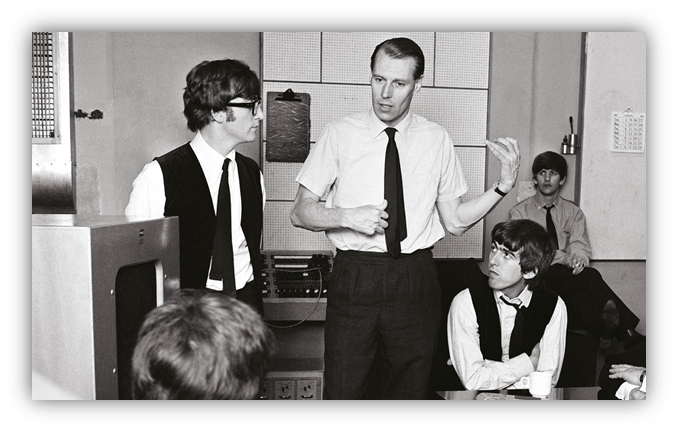

After playing through some songs and engaging in a bit of discussion about their musical abilities, Martin still wasn’t convinced of their talent. Before recording another song, he asked if there was anything they didn’t like about the studio or set up.

George Harrison, who was never one to shy away from a cheeky comment, replied, “Well, for a start, I don’t like your tie.”

Harrison was poking fun at Martin’s formal, upper-crust appearance. It’s the sort of thing that could have tanked their recording career before it even started.

Martin, however, was amused.

He appreciated their sense of humor and later cited that moment as part of why he believed they had something special. They weren’t just talented musically, they had charisma and a bold attitude. These boys weren’t the usual deferential, polished musicians he was used to.

They had personality, wit, and confidence, and that played a crucial role in his decision to sign them.

The session led to their first official contract with Parlophone, a subsidiary of EMI.

It was the official beginning of The Beatles’ storied relationship with EMI, and the beginning of Norman Smith’s role in shaping their early sound.

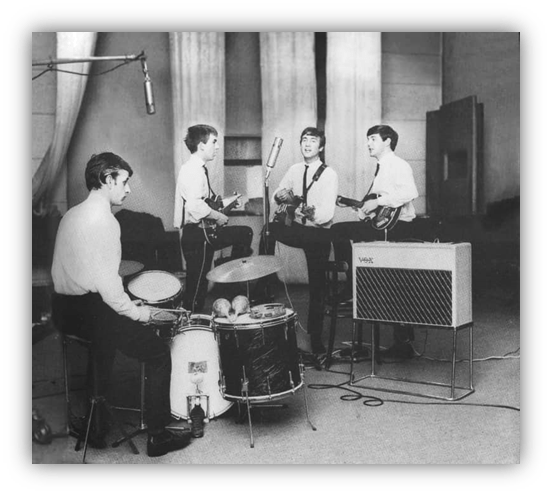

To get that sound, Smith broke the EMI rules.

He recognized The Beatles as a live band, so he cleared the room of all the sound baffling screens and had them set up close to each other as they would do at a regular gig.

Then, rather than put the microphones close to the amps and separating them with screens as the rules specified, he placed the mics twenty or thirty feet away to pick up both the instruments and the room’s natural reverb.

This meant that the instruments would be picked up by every microphone. This would make mixing more difficult, but resulted in the live sound that he and Martin wanted. He also knew that The Beatles’ equipment wasn’t very good.

He had to make their tiny Vox amps sound big, so he used EMI’s echo chambers to turn the sparse source sounds into something more rich.

His own experience performing told him that by physically arranging the Beatles as if onstage, he preserved their interplay and spontaneity, helping them retain their raw live energy, even after multiple takes. His use of echo and the room’s ambience gave those early records their fresh drive. It helped define the early “Mersey Sound.”

Smith engineered the first six Beatles albums, from Please Please Me to Rubber Soul.

He welcomed small but significant studio experiments — like rearranging microphones, tweaking reverb levels, balancing bleed — to give each record its own character.

These nuances grew into more radical innovations under engineer Geoff Emerick, but they began with Smith’s insistence that every album should sound distinct.

He even taught Ringo Starr how to play bongos for “A Hard Day’s Night.” But learning an instrument, even another percussion one, can be hard. Starr didn’t get it right away. So Smith overdubbed the bongos. They’re hard to pick out in the full mix, but listen to just the drums and bongos here:

In 1965, The Beatles were recording their fifth album, Help!. They needed one more song to complete the record.

Smith happened to have lyrics he had written in his jacket pocket. It was called “Don’t Let It Die” and he nervously played it for Paul McCartney, who said it’d be a great song for Lennon to sing. Smith played it for Lennon and he agreed. As it was a Friday, they planned to record it the following Monday.

Music publisher Dick James happened to be in the control booth while all of that happened and offered Smith £15,000 for the song. Behind James’ back, Martin shook his head and mouthed the word, “No.”

While James wasn’t exactly a swindler, he would become known for taking advantage of songwriters. Smith asked for time to think about it.

Over the weekend, The Beatles realized they hadn’t recorded a song with Starr singing lead, and their fans expected a Ringo song on every album. They recorded “Act Naturally” instead of “Don’t Let It Die” but said they’d do it on their next album.

They didn’t.

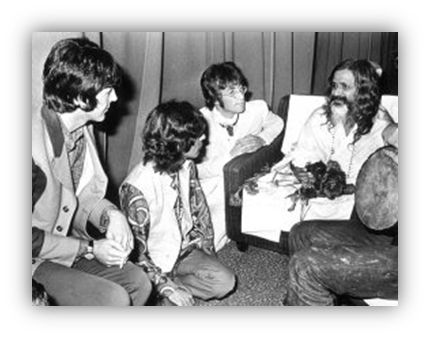

In an interview when Smith was 83, he said he thought it might have been the influence of drugs or the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

Whatever it was, The Beatles were in a different headspace. and no one mentioned “Don’t Let It Die” again.

Regardless, Smith very nearly didn’t work on that next album, Rubber Soul.

EMI had just promoted him from engineer to producer, and he was ready to start immediately. Still, The Beatles asked him to engineer one last album for them, and how do you say no to The Beatles? They were his pals. He engineered for them while starting his producing career.

Rubber Soul was The Beatles’ first foray into psychedelia.

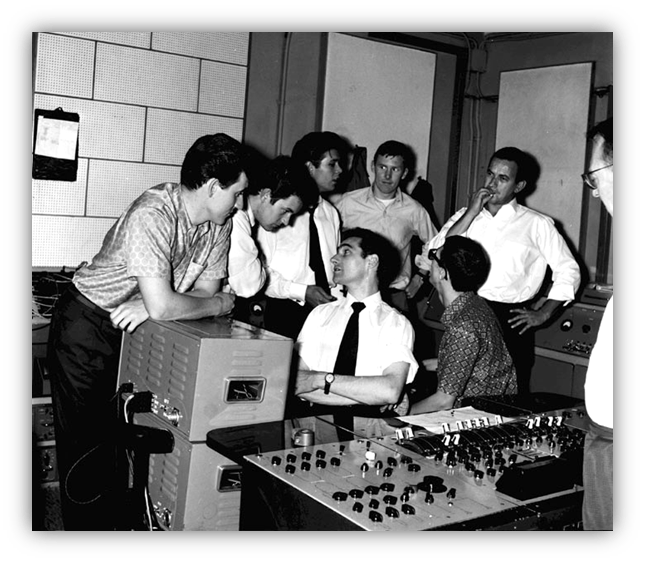

Smith later said that he “didn’t really understand psychedelia” but he knew that’s where music was going. He kept that in mind in his new role as producer, which included A&R. He was to go out and find promising artists to sign to Parlophone.

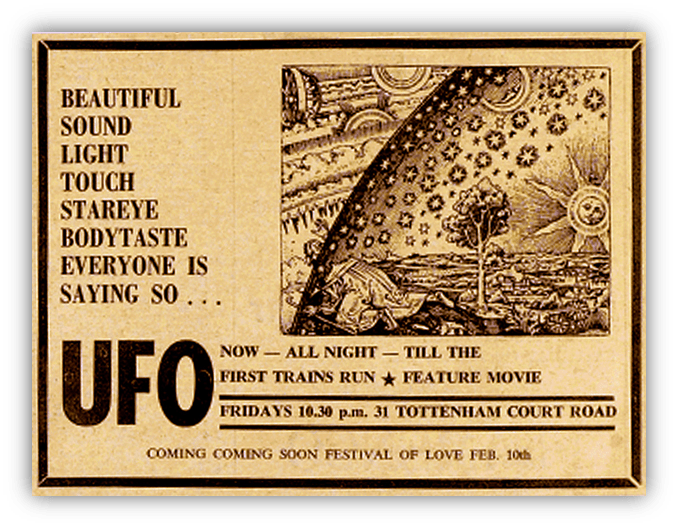

He visited the UFO Club, ground zero of the burgeoning underground psychedelia scene.

It was only open for less than a year — and at two different locations — but its influence on British music was enormous. The musicians who played there include Jimi Hendrix, The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown, Procol Harum, The Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band, Pretty Things, and more. The house bands were Pink Floyd and Soft Machine.

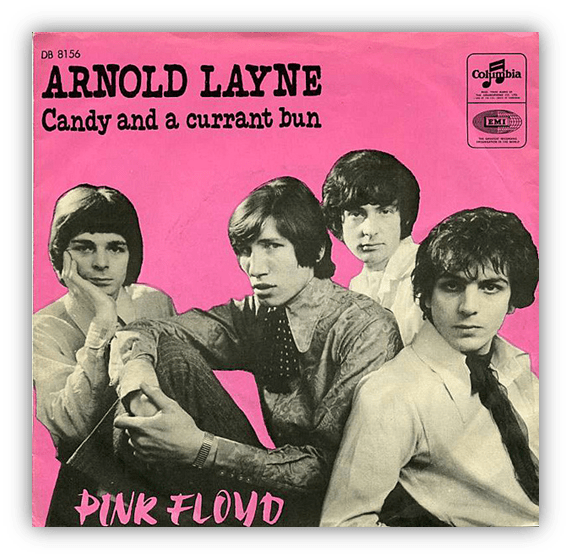

Pink Floyd and their psychedelic light show impressed Smith the most.

He later said:

“What I saw absolutely amazed me…. I was still into creating and developing new electronic sounds in the control room, and Pink Floyd, I could see, were exactly into the same thing; it was a perfect marriage.”

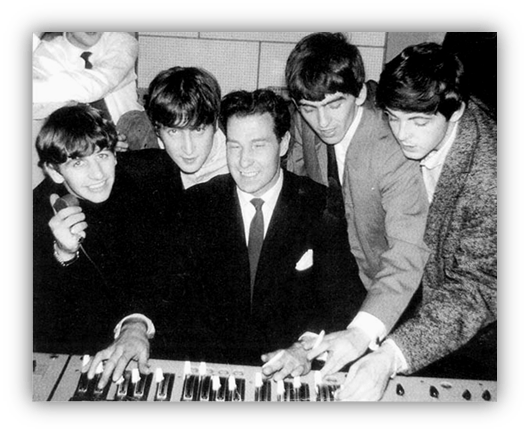

Sensing Pink Floyd’s commercial potential — they already had a dedicated following — he signed them in early 1967.

He even persuaded EMI to give the band an unusually large £5,000 advance against royalties.

But the band was unsure at first.

Their first single, “Arnold Layne,” had been produced by Joe Boyd and they wanted to work with him again.

They changed their minds after Paul McCartney unexpectedly walked into the studio, put his hand on Smith’s shoulder, and said, “You won’t go wrong with this bloke as your producer.”

Smith didn’t act as a boss or money man, but as Pink Floyd’s fellow sonic explorer.

He developed a friendship with them that went beyond the typical A/R man.

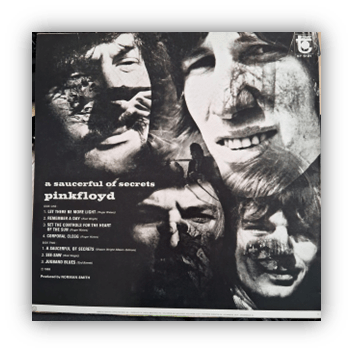

“See Emily Play” was the band’s second single and the first they did with Smith. It was a hit. Smith produced their first three albums, the groundbreaking The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, and the well-received A Saucerful of Secrets and Ummagumma.

On the song “Remember A Day” on A Saucerful of Secrets, drummer Nick Mason had trouble with the part.

As he had done with Starr and the bongos, Smith played it himself.

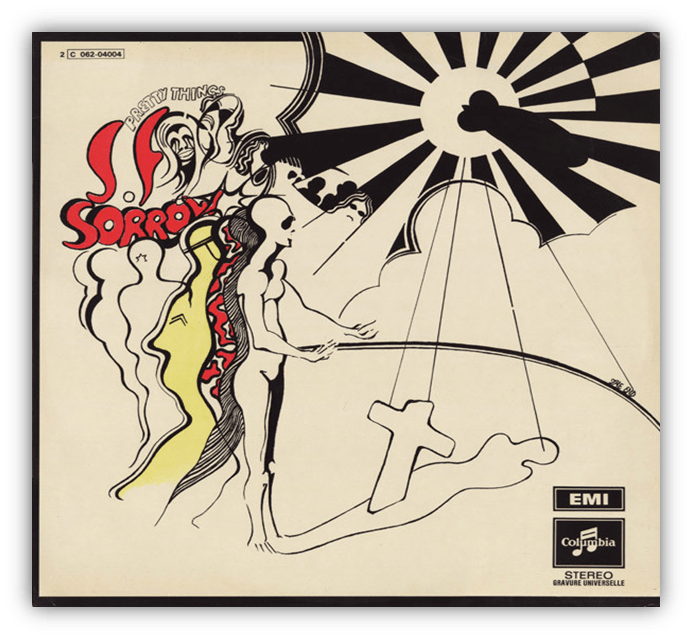

Smith produced Denny Laine, Barclay James Harvest, and Pretty Things:

To include their S.F. Sorrow, one of the first concept albums.

He also did live albums for The Temptations and Stevie Wonder, both recorded at a London nightclub called Talk Of The Town.

All through these years, Smith played semi-professionally on piano or drums at clubs around London.

He recorded demos of the songs he wrote. At the start of the 1970s, as the Beatles broke up and Pink Floyd changed guitarists after Syd Barrett’s mental breakdown, Smith took the advice of fellow producer Mickie Most.

When he heard Smith’s demo of “Don’t Let It Die,” the song he offered The Beatles years before, Most told him to release it exactly as it was. That spontaneous encouragement gave Smith the confidence to put out the track himself.

“Don’t Let It Die” reached #2 in the UK.

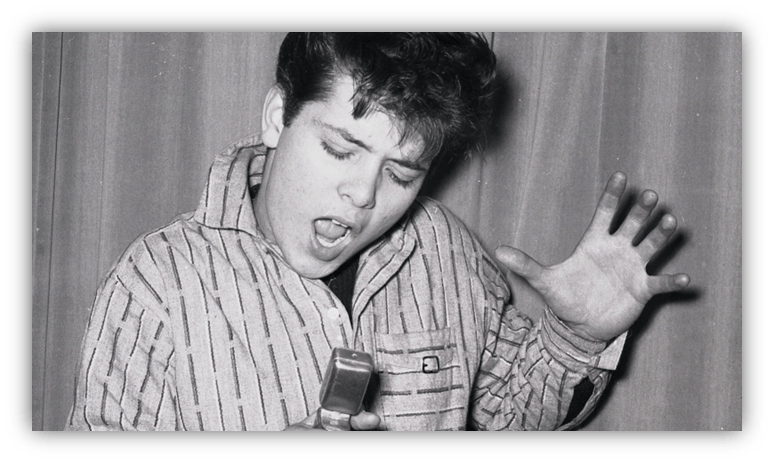

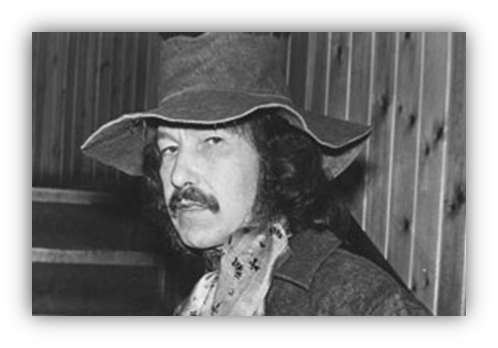

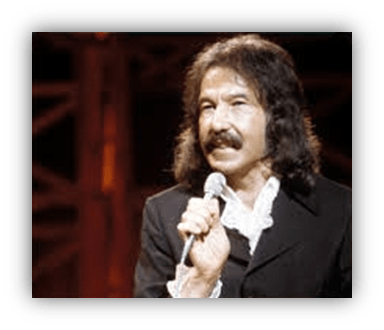

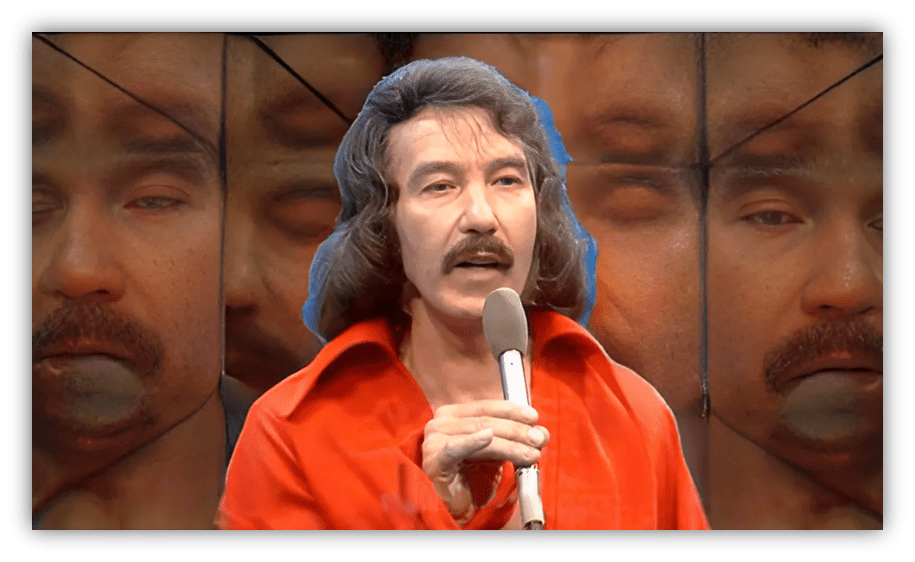

He grew his hair and a mustache, dressed in the style of the early 70s, and assumed the stage name Hurricane Smith. He knew the record buying public — mostly teenagers — wouldn’t rush out to buy records by a 48-year-old boffin.

So he deliberately transformed himself from a buttoned‑down studio engineer…

…into a front‑and‑center performer.

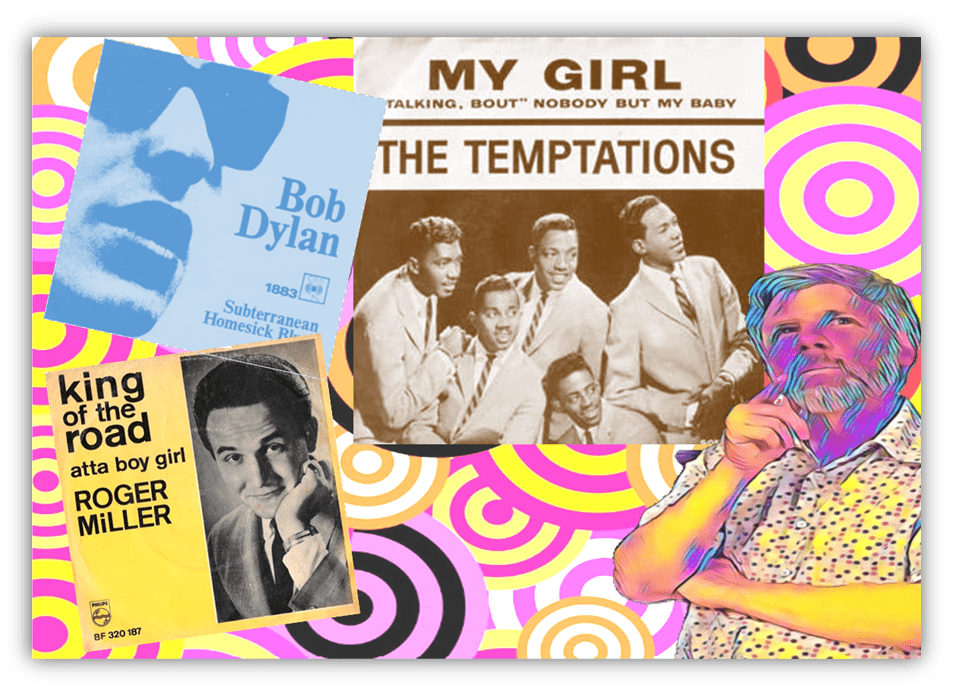

As contemporary as his new looks were, his music had much the same 1930s music hall sound that he loved in The Temperance Seven.

While Paul McCartney’s “When I’m Sixty‑Four” and “Honey Pie” are in that same idiom, there’s no evidence that McCartney influenced Smith. That sound had been ingrained in Smith much earlier.

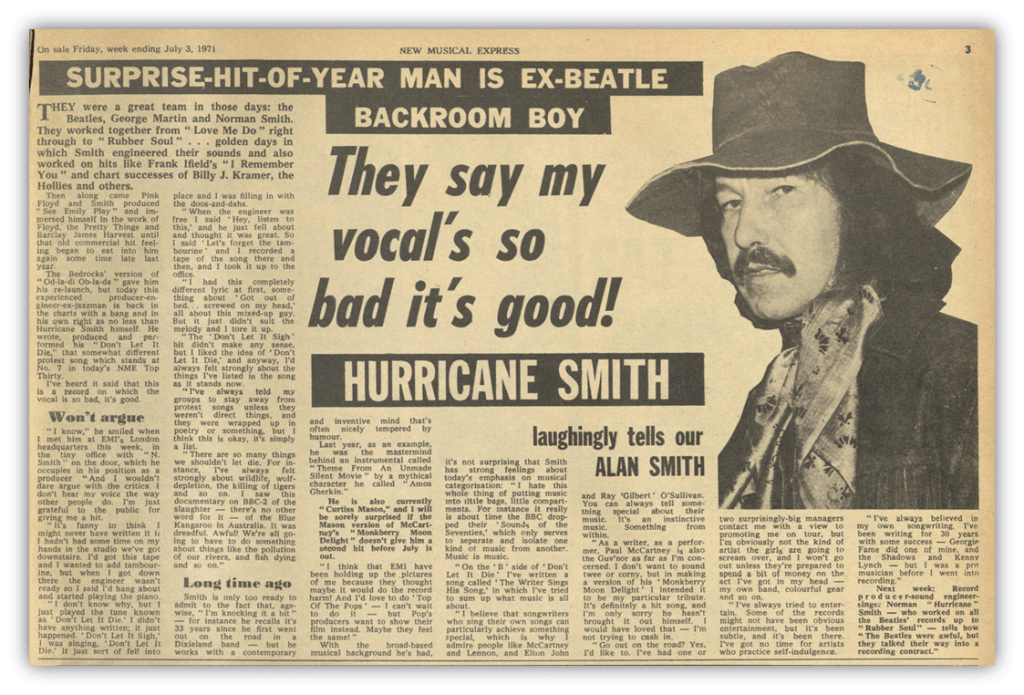

His voice was, let’s say, quirky. It was raspy but not whiskey soaked like Rod Stewart’s. The New Music Express headlined an article about Smith with, “They say my vocal’s so bad it’s good!”

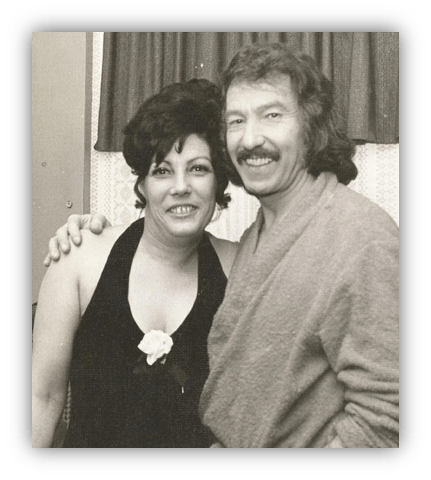

His second single, “Oh Babe, What Would You Say,” was written by his wife, Eileen.

She stayed out of the spotlight, and his memoir talks more about The Beatles and Pink Floyd than about his personal life, so not much is known about her musical background. He did say that it was a “perfect marriage” and that she drew inspiration for the song from their early romance. When they were young, he was too shy to ask her to dance.

Eileen has no other credits in songwriting royalty databases. It appears to be the only song she ever wrote. It’s possible, though this is just speculation on my part, that he wrote it and gave her credit. A song with diminished chords isn’t the work of an amateur, it more likely comes from someone with a Jazz background. Again, that’s complete conjecture. I haven’t seen anyone else suggest it.

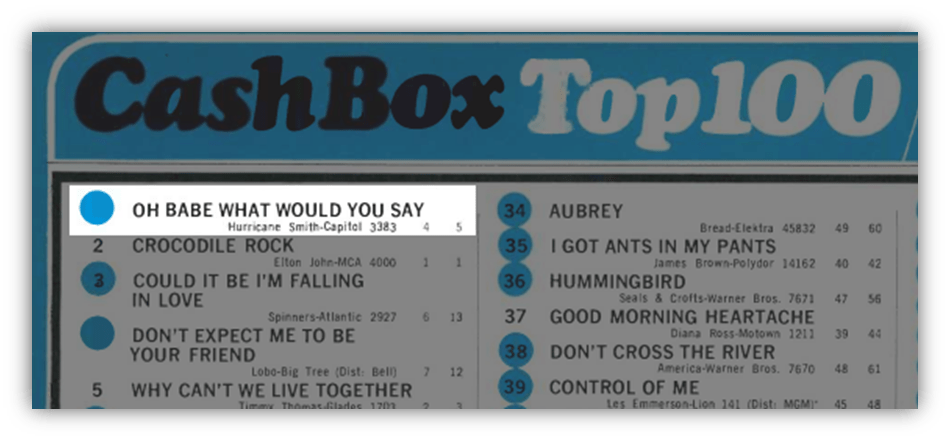

“Oh Babe, What Would You Say” went top ten in charts around the world.

It hit #1 on Cash Box in the US.

He made some TV appearances and toured the UK cabaret circuit twice behind the song and album. Those were his only tours. Subsequent singles like “Who Was It?” and “My Mother Was Her Name” were lesser hits in the UK but nowhere else.

His 1973 album, Razzmahtazz Shall Inherit The Earth, was his last on EMI.

In 1977, he released I’m Hurricane-Fly Me! on the much smaller Pye Records. Neither produced any singles.

He retired to Surrey to raise horses but occasionally produced music, notably for former Moody Blues and Wings member Denny Laine. Smith even played trumpet on the 1980 Kilimanjaro album by Teardrop Explodes.

In 2004, he released one final album called From Me To You, named after The Beatles song.

It included a cover of that song plus new recordings of “Don’t Let It Die” and “Oh Babe, What Would You Say.”

He was also a regularly featured speaker at Beatles conventions.

It was at such a convention that he introduced his book, John Lennon Called Me Normal in 2007. While there, he performed “Oh Babe, What Would You Say.” It was his last public performance.

Eileen passed away in 2006, and Norman “Hurricane” Smith followed her in 2008. He was 85.

Smith’s calm intelligence created a nurturing, collaborative environment.

His inventive use of effects and close attention to performance detail provided both The Beatles and Pink Floyd, with sonic palettes that helped launch their careers.

And his time as “Hurricane” reminds us:

That even the gentlest of technicians may have star power buried inside.

Hurricane Smith is a great stage name – even if the destructive power of a hurricane isn’t matched by the style of his records.

I like his singing voice. Its unpolished but distinctive. I prefer Don’t Let It Die over Oh Babe. Although I wouldn’t go over a 7 for it, its great that he got the recognition and his own moment in the spotlight. Especially as he was advancing in age compared to the majority of his chart contemporaries.

I’m familiar with Norman from reading lots about The Beatles and for his work with Pink Floyd. I did not know that he’d offered a song to The Beatles. Very much in the camp that its a good thing he didnt give the rights to Dick James and held on to it til the time was right.

Thanks for this Bill, great work as ever.

I like his voice, too. I remember “Oh Babe” on the radio when I was a kid and it was delightfully different. I’ve always liked it. I heard “Don’t Let It Die” as well, but it didn’t have the same impact over here.

You, more than any of our regulars here, might know his instrumental, “Theme From an Unmade Silent Movie.” Tony Butler used it as the theme song of his radio program and Wikipedia says it’s the unofficial song of Aston Villa FC.

If The Beatles had done “Don’t Let It Die,” it would have been an even bigger hit, but it’s gratifying that it did well without their name on it.

I didn’t know about Theme From An Unmade Silent Movie. Tony Butler was on a variety of West Midlands / Birmingham stations, it looks like its popularity is very localised. Trying to work out why it was adopted by Aston Villa but seems to be no local connection to Norman, he wasn’t from the area. A very random choice. Looks like they’ve also used Black Sabbath Crazy Town at times which is much more appropriate to the city and for.whipping up an atmosphere.

Does anyone recall the strange way that (The) Hamilton, JoeFrank and (The) Reynolds sung a particular lyric on “Falling In Love?” I always heard “fawwin” instead of “falling” in the chorus. The inflection is oddly endearing.

It’s the same when I hear Hurricane Smith intone “lollipop.” Adorable.

No real point to this riveting story. Carry on.

You’re thinking of the version by Hamilton, JoeFrank and Elmer.

Here’s what got me interested in Hurricane Smith. This is my friend Duane Spencer doing a stripped down version of “Oh Babe, What Would You Say?” He just started doing it recently, and about the same time, a Facebook friend posted the original, saying it’s a great song. He’s right.

https://youtu.be/Qf4BtHP-zIU

Great piece, Bill. I learned a lot from it. I’m not a huge fan of “Oh, Babe…” but I’ve never heard “Don’t Let It Die” and will give it a listen now. Have a great weekend.

Great write-up – I had no idea who this person was, but… wow – what an impact.

I only knew Hurricane Smith as a one-hit wonder with “Oh Babe”, but I liked his voice and wished that he had done more. Little did I know…