Ooh, that smell

It’s the 21st Century.

When we go to concerts, we don’t look forward to smelling anything.

In some venues, however, you can’t get away from the smell of spilled beer, smoke that may or may not be legal in your state.

Or the noisy reappearance of the first nine drinks of someone celebrating their 21st birthday.

These odors are part of the atmosphere, but they aren’t part of the performance. There once was a time when the host provided scents that went along with the music.

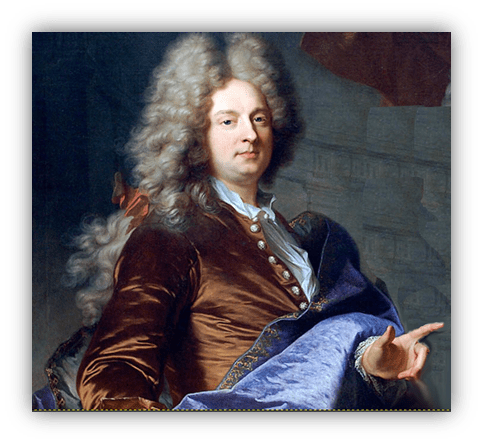

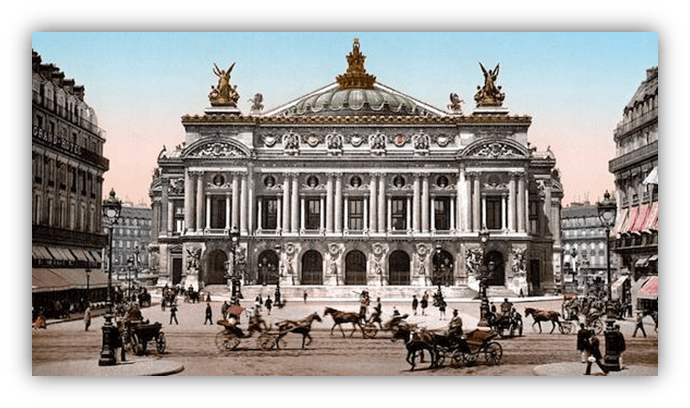

Let’s imagine going to a European concert in 1650.

When you walk into the salon, candlelight flickers on mirrors, powdered wigs float around the darkened room like low, fluffy clouds, and a small orchestra plays under an embroidered canopy.

As the first violins take up a slow French air, a servant moves through the room, trailing a plume of scent — rosewater from a silver bowl, a spritz of ambergris on a perfumed glove, or the smoky sweetness of frankincense.

The music and the scent rise together, not by accident but by design.

The aristocracy staged concerts that engaged ears and noses at the same time. For about a century, scent was an active feature in elite musical life — a deliberate ingredient in the recipe for ceremony, intimacy, and displays of social power.

Nowadays, we think of concerts as sonic events:

Seats, a stage, and an audience listening.

But mid-millenium Europeans thought differently.

Public and private entertainments were multi-sensory affairs by default. Rooms were crowded with people wearing perfumes and powders, and lit with candles (even unscented candles have a smell). Food and drink circulated. Textiles and fresh or dried flowers added their own aromas.

Combining music with scent amplified mood, signaled status, and concealed the less pleasant odors of life before indoor plumbing. It was even part of the act: scent could reinforce the themes of a performance or, just as importantly, the status of its patrons.

Scent carried social signifiers.

Certain fragrances — attars of rose, orange-flower water, civet, ambergris — were expensive, exotic, and associated with elite consumption.

To perfume a music room was to proclaim wealth, taste, and the wherewithal to command shipments of spices and the services of skilled apothecaries.

Combining perfume and music was a kind of shorthand for:

“This is a civilized, elegant space.”

Also:

“I have money and power.”

Early-modern scent culture had a surprising technical vocabulary.

Fragrances were not simply “pleasant” or “unpleasant”; they were constructed from distilled essences, floral waters, oils, and animal products.

Rose, orange-flower, jasmine, and bergamot were plant-derived staples.

Resins like frankincense and myrrh burned well for incense, while animal secretions like ambergris (aged duct bile from sperm whales) and civet (diluted discharge from the perineal glands of civet cats) were prized for their tenacity and depth — especially in northern climates where floral notes evaporated quickly.

Apothecaries and perfumers knew how to make fragrances last in drafty, candlelit rooms:

- Fixatives were added to slow down evaporation.

- Cloths and ribbons could be steeped overnight and then placed around the room.

- Scented handkerchiefs and small silk sachets could be distributed to guests as keepsakes.

These were not party tricks. They had practical know-how behind them.

Perfume could be introduced into musical gatherings in several ways.

Each method created a different relationship between scent and sound:

Perfumed bodies and garments

This is the simplest technique. Guests arrived already doused in scents. Men and women wore scented gloves, handkerchiefs, pomanders (small fragrant balls), and sachets inside their clothes. The musicians wore these, too.

In an intimate salon, the mingling of personal fragrances and the close proximity of performers mixed smell and music organically.

The risk here, of course, is the host had no control over which scents people wore, and they may have clashed with each other.

Perfuming the room

Hosts perfumed the air with standing vessels of rosewater, incense burners, or trays of orange peels and herbs placed around the room. For a masque or an allegorical music performance, these items might be arranged as part of the décor:

A bowl of aromatic herbs at the foot of a prop altar or camphor chips tucked inside floral arrangements:

So that scent was visually integrated into the stage design.

Timed scent effects

The most theatrical method used scent as a timed effect. Just as a composer might cue the string section to enter for an emotional crescendo, stage managers would time the waft of an incense burner or the shaking of a pomander to coincide with musical climaxes or scene changes.

Handkerchiefs dipped in rosewater could be waved at a moment of farewell; a servant might pass a perfume-laden glove to the principal ballerina as she danced.

These choreographed introductions of fragrances matched the music. They used smells the way Metal bands use pyrotechnicss.

Perfume worked on audiences psychologically.

- A warm, sweet scent might soften a mournful aria.

- The brightness of citrus at the arrival of a prince could make the arrival feel more exotic and impressive.

- A sudden waft of incense at a funeral scene made the moment feel more solemn.

Because people were used to associating smells with places, memories, and social meanings, perfumed effects added symbolism that could be harnessed by composers and their patrons.

This wasn’t just art for art’s sake. It was political theater.

Perfume signaled access to overseas goods and expertise. Theatrical choices — which composers were hired, which scents were used, timing— made statements about the family’s cultural sophistication and political orientation. A perfumed concert fused aesthetic taste with diplomatic messaging. You could, in so many words, smell the court’s alliances.

There were risks, of course. Overuse could smother a room, and competing perfumes induced confusion. The small spaces in which many salon concerts took place meant that a single overpowering scent could overwhelm listeners and performers alike. Part of the craft, then, was restraint and timing. A failed performance reflected poorly on the patron’s status.

I often complain about bad light shows. 17th Century me might criticise the way the show smelled.

Now, what scents were used with which compositions? That’s hard to say.

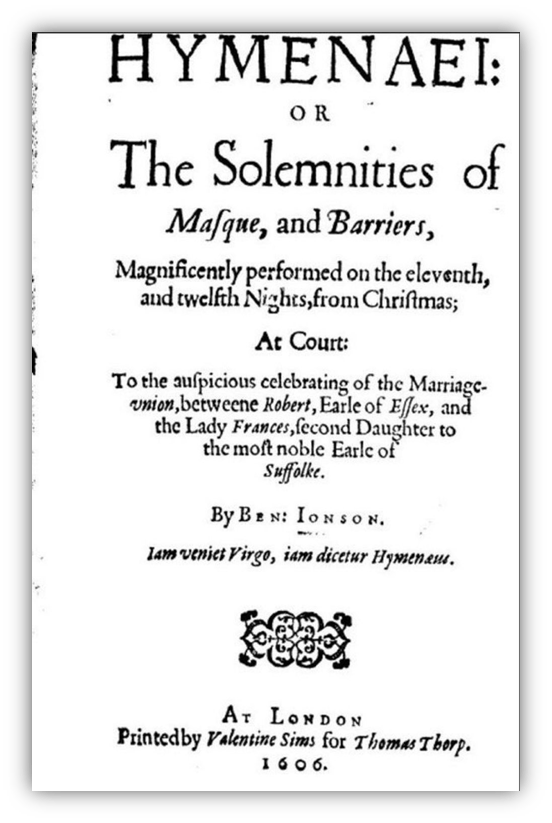

Few 17th Century documents survive that say something like, “frankincense was burned at the performance of Ben Jonson’s Hymenaei.” However, we know that perfumed concerts happened and scholars have linked dates of performances with theater, household, and court inventories.

But Jonson’s printed stage directions for a 1606 performance of Hymenaei give us pretty high confidence that flowers and garlands were physically present onstage, and perhaps in and around the audience. Syringes that might have been used to spray scents are documented to have been there.

French composer Jean-Baptiste Lully’s Les Plaisirs de l’Île Enchantée has been matched with orange-blossom water and other floral waters like rose and jasmine.

Perfumes were also applied to gloves, fans, garments and even sprayed in rooms. This was specifically for a 1664 performance at Versailles for Louis XIV. We’re less certain about other performances.

There’s strong evidence for lavish multisensory productions at Mantua, Italy in general.

We can infer that Claudio Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, which premiered there in 1607, used incense, laurel, myrtle, and garden flower scents.

While there are receipts for these items, there’s no direct documentation that names a specific perfume used at the L’Orfeo premiere.

By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, changes in taste, hygiene, and concert culture reduced scent in musical life. Concerts got larger and more available to the public. The ideal venue for a public concert was a symphony hall or opera house, not an intimate salon.

It was hard, if not impossible, to control timed changes in scent in those big spaces.

Enlightenment sensibilities also shifted aesthetic priorities toward the analytical.

It was the Age Of Reason, after all. Staging the other senses began to clash with new ideals of pure music appreciation.

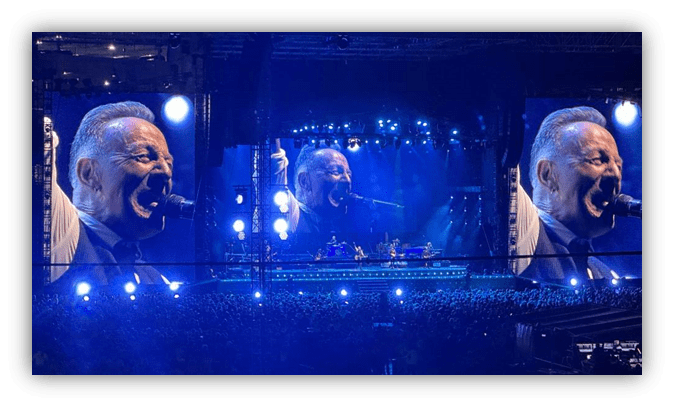

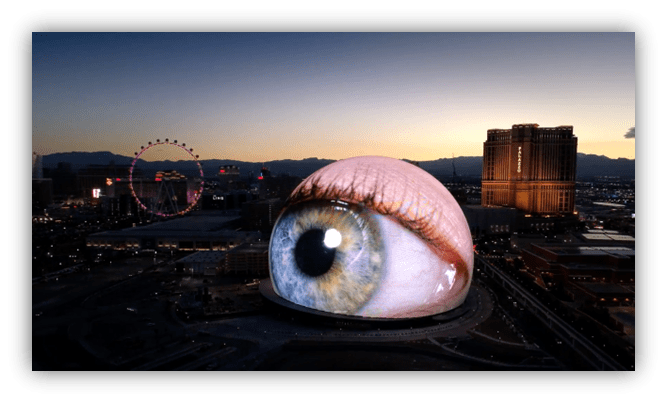

Still, the Baroque taste for spectacle lives on in modern productions that use fog machines, light shows, and jumbotrons.

Perfumed concerts were not merely an ordered sequence of notes, but an orchestrated event in which the air itself had meaning. The scent designer, the apothecary, the harpsichordist, and the patron all shared roles in composing an atmosphere. This sensibility felt rich. Literally.

We should think about what a concert once was, and what it is now.

It used to be a complete experience.

Next time you attend a concert, notice if your other senses are put to work.

Sure, we have light shows, but that’s only sound and sight.

Touch, taste, and smells contribute to an atmosphere, and that atmosphere — like rhythm and melody — can be crafted.

But only if the artist chooses to do so.

I wonder if someone using smell in that way now would just come across as a gimmick. Like cinema with Smell-O-Vision.

My first thought was that scent would be used to mask more unsavoury smells of day to day life and add a touch of class to proceedings. Even in palaces if what I’ve read about the French nobility is true; that they didnt bother with toilets and would just go behind a curtain in whatever room they were in. It wasn’t only the peasants that were revolting.

Fascinating stuff as always, thanks Bill.

Imagine trying to scent a festival like in your article yesterday. Impossible!

One experience with “smell-o-vision”. When I would take my daughter to the Lego museum, there was a short movie that was shown in “4-D”, meaning that there were special effects in the theater, such as a mist that would descend upon us when the characters in the feature were on a boat. When the skunk character would get anxious, he would involuntarily let out his skunk smell, and we got to experience that too.

Didn’t care for it.

I also think that scents were pushed historically because there were already bad scents around by default, so they had to work harder at it. With closed sewage plumbing and personal hygiene improvements, our day lacks a lot of those ubiquitous smells of the past.

I’m ok with a good smell, but it sure helps if they’re kinda natural and all. Buying scented candles or glade plug-ins can be expensive and the scents can be harsh and overwhelming. As far as spray-can scents go, I still think that there will come a future day when they’ll look back aghast that we bought cans full of petrochemicals and sprayed them in enclosed areas to breathe, trusting the corporations that sold them not to include any ingredients that might be harmful to us.

But if I were in a room with a full chamber pot steaming behind a curtain, I’d probably spray a can, too.

Right there with you, buddy.

Scents-ational. This article didn’t whiff.

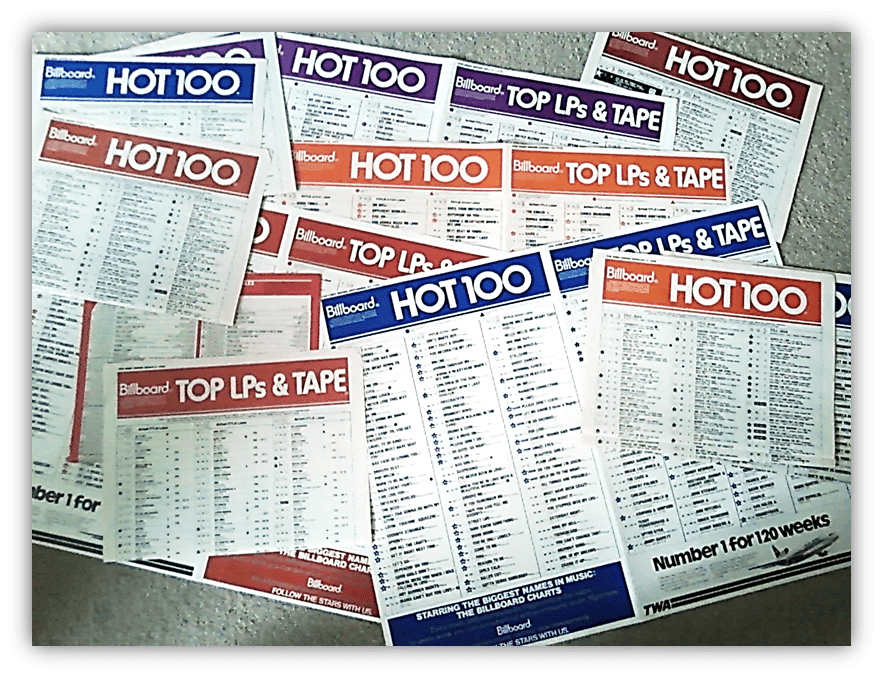

OK. All bad puns aside, I appreciate this take on a phenomenon I hadn’t ever thought about. The only time I thought about the sensory connection with music was the rare times that artists released records with some sort of olfactory element — the Raspberries’ debut (which Casey Kasem talked about so many times), and I think Prince did something with one of his ’80s/’90s releases.

These days, I’d just be grateful to avoid not only the smells of particular intoxicants but also the colognes/perfumes of folks decked out for the show.

Have a good weekend.

Fascinating stuff about something that is very foreign to us now, connecting sense of smell to music. And the effort that was put in to it and the source of some of the scents was surprising. Particularly, as a cat owner, the concept of any sort of discharge from a feline being prized gave me pause (paws?). I am a lover of scented candles, and when I was in the recording studio a number of years ago, I had the producer light a bayberry spice candle to calm me before the session started. We made a video of the session and you can see the musicians talking about a mint chocolate chip candle and getting excited. I have many candles of a number of different scents in the house and light them frequently, though yesterday, I lit too many at once and it was giving my wife a headache, so there is a limit. But I don’t think I have made the connection between smell and hearing. Not sure that I can, but I’m willing to try. I have nothing to lose by combining 2 things I love.

It was an opportunity to see somebody famous. I attended the promotion of a new perfume by Catherine Deneuve at Neiman Marcus. It was my first time at Neiman Marcus. I should’ve worn pants. Too costly, the perfume. I didn’t get my autograph. I didn’t get a chance to express my admiration for her performance in Repulsion. Denueve plays a tortured person while beautiful. No makeup. Just talent.

Joanna Newsom performed “On a Good Day” on Letterman. I never thought about what the stage might’ve smelled like, until now.

Really interesting topic, V-dog.