In my article about Dietrich Nikolaus Winkel and Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, I mentioned that, in addition to their work on the metronome, each invented musical instruments that play themselves.

Self-playing instruments like the componium and the panharmonicon were popular across Europe, at least among people who could afford them, but what did American ingenuity do with the idea?

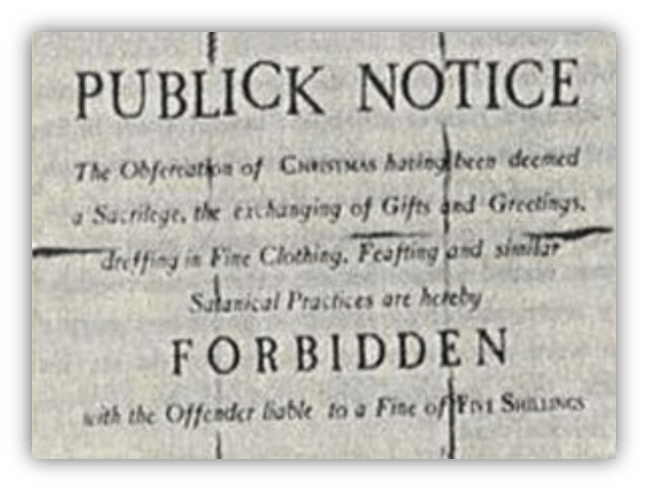

Anthony Stoddard was an Englishman who arrived in Massachusetts in 1639 as part of the Puritan Great Migration.

His son Solomon became a respected pastor at the Congregational Church in Northampton, and supported “The Halfway Covenant,” an easing of the rules over who could receive Communion.

Solomon’s son Anthony was also a pastor, and his great-grandson Nathan fought against the English in the Revolutionary War. Nathan died in battle when he was hit by a cannonball at Fort Mifflin, near the field that is now known as the Philadelphia International Airport.

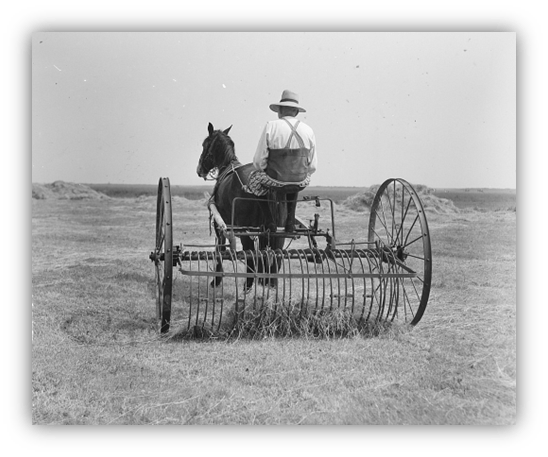

Nathan’s grandson, Joshua C. Stoddard, was born in 1814, in Pawlet, Vermont. Educated in public schools, he went to work on his father’s farm and became an adept beekeeper. Honey seems to have been a substantial part of his income for most of this life, first with his father and then on his own farm in Worcester, Massachusetts.

He was a religious man and believed the end of the world was nigh. But he was also described as “something of a poet” and loved music. He had the curiosity and craftsmanship of an inventor and earned sixteen patents over the course of his life.

Most of these were for farm equipment, like the horse-rake and hay tedder, both used for drying and preventing decay in newly cut hay. He also invented a fruit paring machine. Among his non-agricultural patents were two improvements to fire escapes.

We can assume that he knew about church organs, and we know he was fascinated by the whistles on steam trains.

He first heard one on his father’s farm. That may be where he got the idea for a new musical instrument.

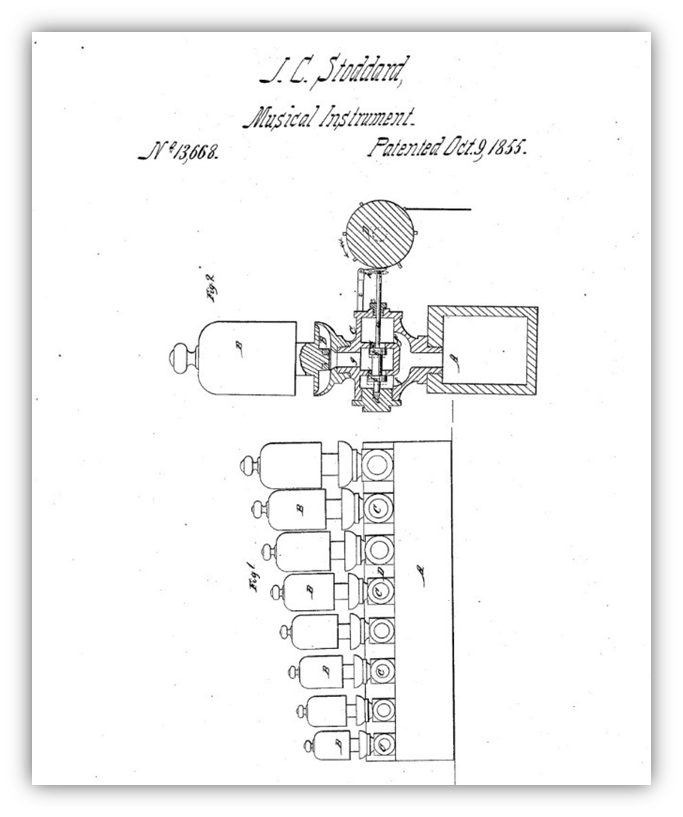

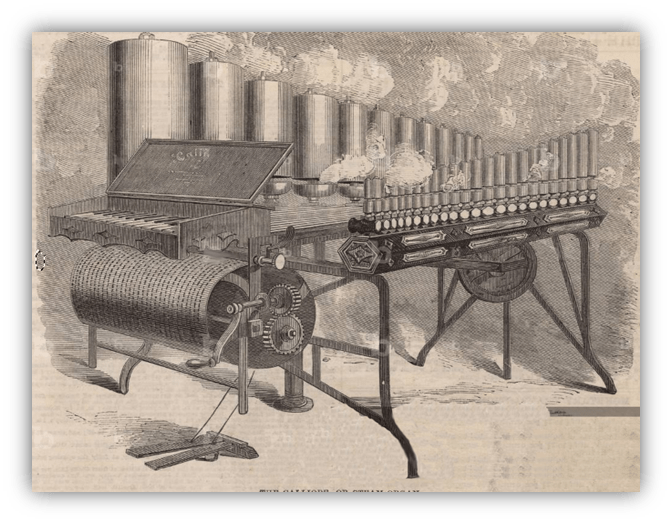

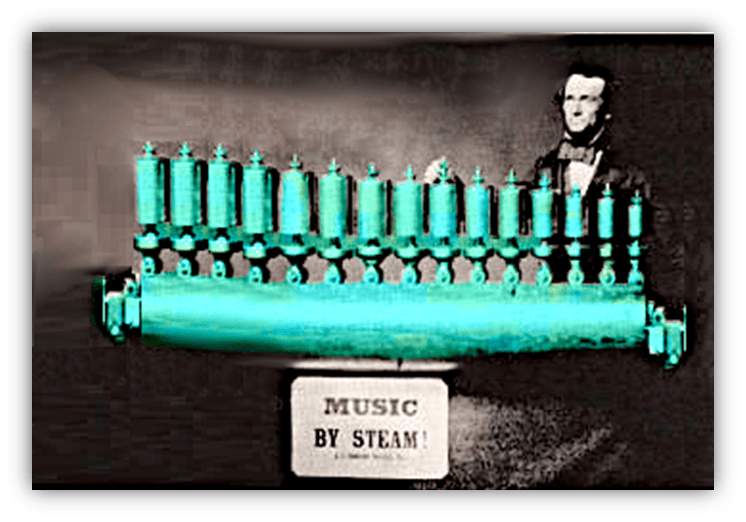

His first version used steam to vibrate bells with the idea to create an alternative to clanging church bells. He soon changed the design to direct steam through whistles of different pitches.

Other steam-powered instruments existed, or were claimed to have existed, but Stoddard was the one to patent it, in 1855.

He called it the American patented steam piano and started the American Steam Music Company that same year to produce and market his instruments.

And while his original design called for a keyboard to be played by a live performer, the company added a model with a rotating cylinder. Pins sticking out from the cylinder would trigger which notes to play, like a music box. The instrument could now play itself.

Stoddard had five brothers and three sisters.

One source says that one brother was captain of the Armenia, a steamboat on the Hudson River, and that it was the brother’s idea to install a steam piano on his boat.

I can’t confirm that, but it seems as likely as any other explanation as to how steam pianos became popular on riverboats, and we do know that the first steam piano on a riverboat was aboard the Armenia. This first use confused people on both sides of the river, and they rushed to the shore to see what was making that sound. Word got around that steam pianos were a crowd magnet and the race to install them on riverboats began.

Steam pianos had only one volume setting, and it was loud.

If steam can power a riverboat or train, its force through a whistle can be eardrum piercing. This is exactly what Stoddard had in mind.

He wanted the instrument to be used at outdoor performances, like parades, circuses and fairs.

They became very popular on the riverboats up and down the Mississippi River, and could be heard from five miles away.

That volume was also a detriment, and the Worcester City Council banned the American Steam Music Company from playing its instrument within the city limits.

Tuning or repairing the steam piano was dangerous work.

Not only could the volume damage the workman’s hearing, he could burn himself on the hot pipes.

Arthur S. Denny, one of the company’s former employees, tried to set up his own company making and selling steam pianos in London.

In 1859, he set up a demonstration at the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park and pursued customers, but no one was interested. It seems to be an American peculiarity.

His redesign allowed the user to adjust the steam’s pressure, and therefore its volume.

Stoddard patented some really clever devices, but he was never rich.

Maybe he wasn’t worried about money because he thought the world was going to end anyway.

As smart and creative as he was, and despite the instrument’s popularity, he wasn’t good at commercializing his invention.

In 1860, just five years after patenting the steam piano, his own American Steam Music Company ousted him.

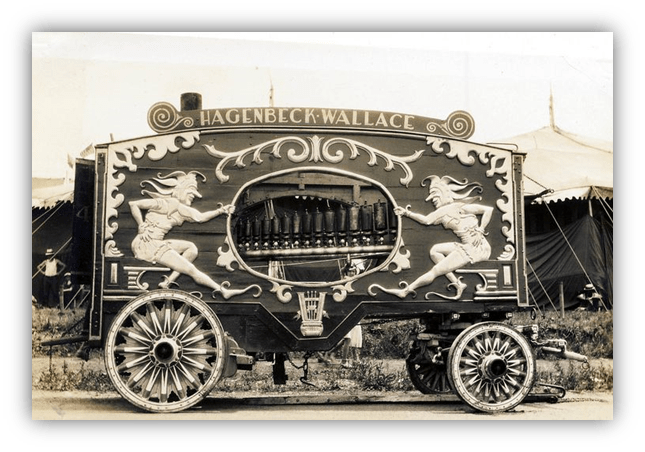

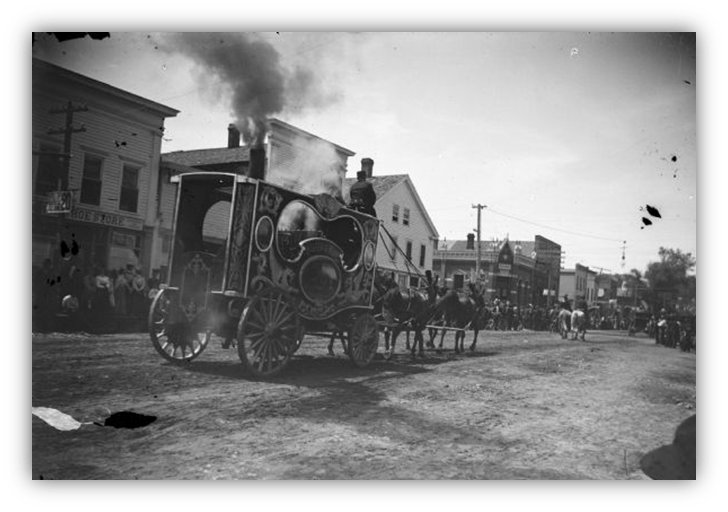

Ten years later, P.T. Barnum used a ferry to get his circus across the Ohio River and heard the steam piano for the first time. He thought such an attention-getting instrument would be a great addition to his traveling extravaganza, and wanted to mount one in a circus cart and have it pulled by elephants at the end of the circus parade.

The parade happened when the circus arrived in a new town.

They’d march all the crew and animals through the town to the fairgrounds or wherever they were going to set up. It’s the best kind of advertising for that night’s show. A loud, elephant-drawn instrument was the perfect parade finale.

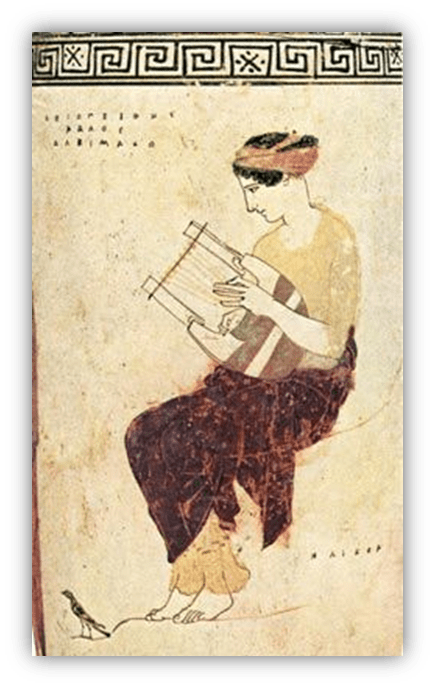

But Barnum didn’t like the name “American patented steam piano.” So he did some research and found the seventh Greek muse.

Her name came from the Greek words “kallos,” meaning beautiful, and “ops,” meaning voice. So Barnum called the “beautiful-voiced” machine after Calliope. That’s the name we know it by today.

Barnum was better at marketing than Stoddard

Interestingly, the Armenia, the first boat to install a calliope, was also the first boat to remove it. Apparently, it took a lot of coal to operate both the boat and the instrument. Still, the calliope remained popular on riverboats, particularly on showboats where they were used to draw a crowd, as Barnum had done.

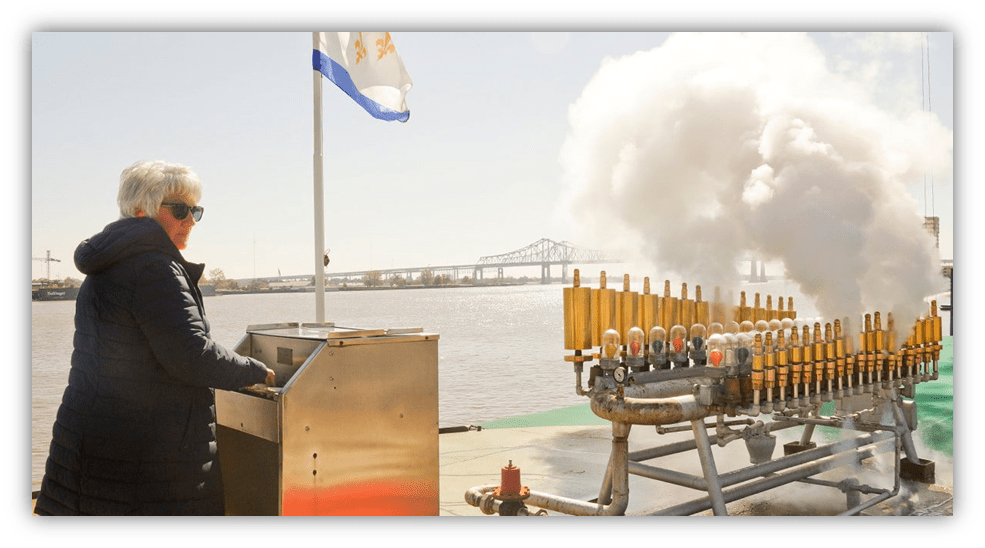

The Delta Queen installed a new calliope in 1960, and this one had the keyboard a safe distance from the very loud pipes.

Stoddard envisioned the calliope as not just an instrument but a means to entertain and call people to gather. Over the years, the calliope evolved, finding its place in various musical genres and cultural settings.

It’s an American classic but its popularity faded as steam was replaced by electricity. Any working calliopes you see these days are unlikely to be powered by coal.

Joshua C. Stoddard died in 1882.

His farming inventions are longer lived than the calliope and are still used every day.

His musical legacy has faded with his steam piano, but he produced a symbol of celebration, nostalgia, and American culture.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Thank you for an informative look at a very intriguing instrument. I went to the circus as a kid but I don’t remember seeing a calliope or hearing one, though I’ve certainly heard recordings of one and the sound is unmistakable. Apparently George Martin wanted to use one for the Beatles’ song “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite” but couldn’t find a steam powered one, so he used recorded samples, and randomly reassembled them.

A few years ago, we visited Circus World Museum in Baraboo, Wisconsin, the one-time site of the Ringling Bros. circus, and they put on a musical show, featuring many different vintage organs and instruments that had been used in the circus over the years. There was no calliope, but it was really awesome. They ended in a medley of Abba songs.

Maybe calliopes would be too loud for Baraboo, but Circus World sounds like fun. I used to live in Sarasota, FL, with winter home of the Ringling Bros. circus. The circus museum is small but John Ringling’s mansion is beautiful.

When I told my bandmate in Pussycat Doghouse that Sarasota High School has a circus program, he wrote “Clown School Dropout.” It still makes me laugh.

I’ve been to that mansion in Sarasota, as a teenager. I remember it being massive.

My wife grew up in the small Derbyshire town of Clowne. I’d never heard of it til I met her. It’s brought me endless entertainment to remind her that she went to Clowne school, learned to drive in a Clowne car, etc. For some reason she isn’t quite so amused.

It was originally called Clune, became Clown and then they added a superfluous ‘e’. They’re fooling no one, it’s still pronounced the same. Bunch of clowns.

The French word for “clown” is “clown” but it’s pronounced “clune.” Maybe Clune got its original name from some French clown.

I’ve been to both Baraboo and Sarasota’s museums — Baraboo’s as a kid, Sarasota’s as an adult. I think I preferred Baraboo’s (but then I was at an age where circuses ruled).

One that I’ve heard of at last. Vaguely familiar with it anyway, even if I’ve never seen one in the wild. Another fascinating backstory as well. Thanks Bill

I am fascinated by the fact that the instrument was designed to be crazy loud…five miles away?? That must have been amazing for the day.

Closest I can get in my collection is an album called Afternoon in Amsterdam. Its 30 minutes of Barrel Organ music, which is a lot like you would hear in an old carousel. Instead of being powered by steam, I think it was hand cranked (or now by electricity), and it included all sorts of instrumental and percussion sounds.

Somehow I have TWO copies of this album in my collection. I can’t even…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nQUS3DKIous

I don’t know if it was Denny’s redesign or some other method but they eventually got the volume under control. Tuning the thing is another matter, I presume because the temperature expands the pipes. Anyway, try this on for size.

https://youtu.be/SFgqDSBba1g

That is pretty fun! Although after 60 (or 20 or 10) minutes that might get old.

I’ve spent many years researching the history of the steam calliope, and I would like to point out a number of factual errors in your story. Please contact me if you are interested in setting the record straight.

We strive for accuracy. I’ll send an email…