If J.W. Pepper had named his new instrument after himself, we’d be talking about the pepperphone.

That might have prevented the misconceptions over who invented it.

Instead, he named it after John Philip Sousa, the famous American conductor and composer. For decades, some folks argued that the sousaphone wasn’t invented by Pepper, but by Sousa himself, or instrument maker C.G. Conn.

We know the truth now, but it took years of research — and a chance purchase in a thrift store — to settle the matter of who invented the sousaphone.

John Philip Sousa was a multi-instrumentalist, composer, conductor, and one of the most famous American musicians of all time.

He had been a bandmaster in the U.S. Marine Corps and his composition “Semper Fidelis” became the official march of the Marines.

While he wrote over 150 classical works including operettas, humoresques, and suites, he’s known as The March King for his 130 marches, like “The Stars And Stripes Forever,” “The Washington Post,” and “The Thunderer.”

Plus, “The Liberty Bell” became the Monty Python’s Flying Circus theme song. It was chosen mostly because it was out of copyright and therefore the comedy troupe wouldn’t have to pay royalties.

James Welsh Pepper grew up in Philadelphia. He always had an interest in the arts, in part because the city was a cultural and industrial center. In 1876, at the age of 23, he opened a music store selling instruments and sheet music.

He also began making instruments and opened a 10,000 square foot facility near Washington Square.

Within three years, his company began publishing music, making it one of the first American firms to publish and distribute band music. Until then, sheet music had to be imported from Europe. It was good timing because brass bands became very popular after the Civil War. Pepper filled his catalog with sheet music arranged for military, school, and community bands.

Sousa moved to Philadelphia in the same year that Pepper opened his business. The two men were still in their 20s. In 1879, Pepper published Sousa’s tenth march, “Globe And Eagle.” Over the years, he published ten more of Sousa’s marches, as well as the operetta “Desiree.”

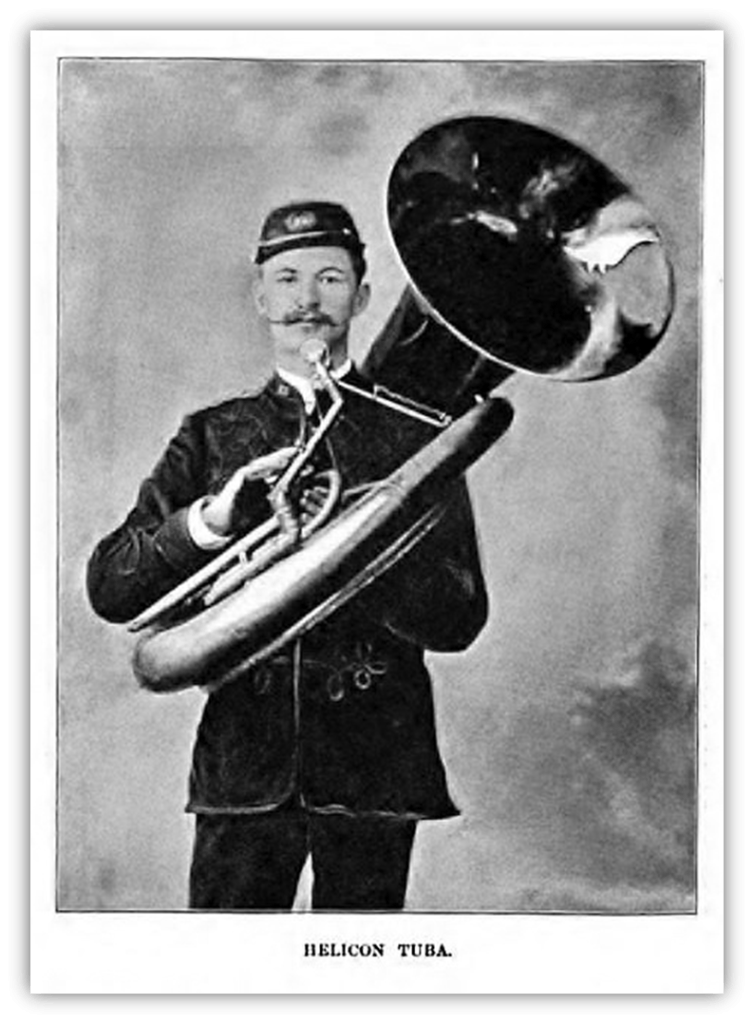

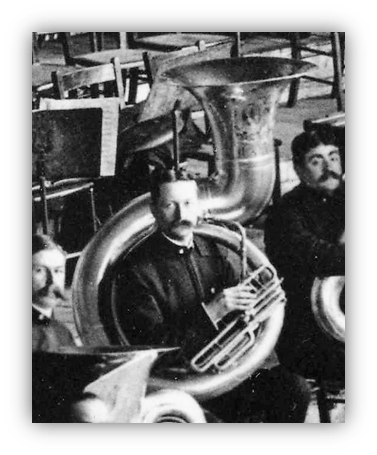

The bass parts of brass bands of the time were played by either concert tubas or something called the helicon, a low brass instrument that wrapped around the player’s body.

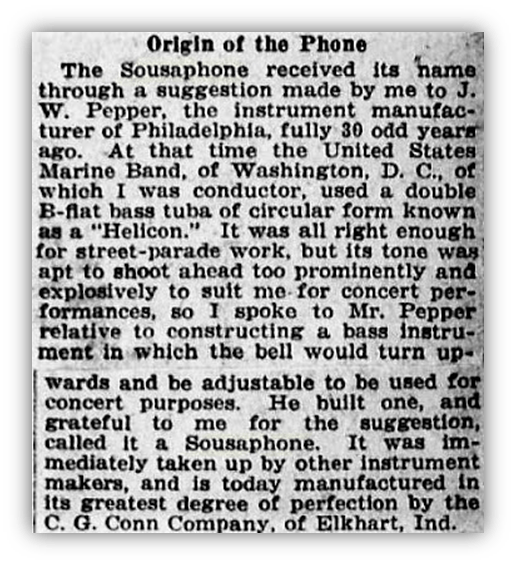

While the helicon sounded alright, it drowned out the other instruments and Sousa didn’t like that it projected its sound forward and to the left.

Sousa asked Pepper to make a similar instrument with a bigger bell for better tone. And he wanted the bell to point straight up, as he said in his autobiography, “…so that the sound would diffuse over the entire band like the frosting on a cake!”

It took three years — because Pepper was running a company so his time and money were in use elsewhere — but he built such a horn and named it the sousaphone because Sousa gave him the idea.

The huge bell pointing upwards gave it the nickname “raincatcher.”

Both Pepper and Sousa thought it was close but not exactly the sound Sousa was hoping for. Sousa used it on tour the following year but Pepper didn’t make another for a decade.

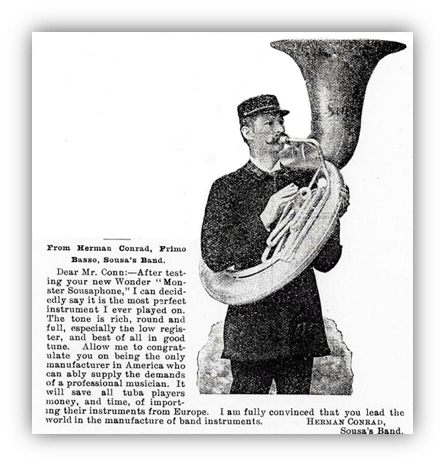

The musician who played the new instrument on that 1896 tour was named Herman Conrad, a German immigrant and one of the best tubists in the world.

He created an eye-catching sight. Not only was the sousaphone huge, Conrad was six feet and five inches tall. He stood out even without the huge brass bell over his head.

With all that attention, both visually and sonically, interest grew in the sousaphone. It didn’t take long for other instrument manufacturers to start making them, including C.G. Conn.

After the 1896 tour, the first sousaphone seems to have gone missing. Conrad and other bass brass players preferred the sousaphones made by Conn’s company, so it looks like no one gave much thought to the whereabouts of Pepper’s original instrument.

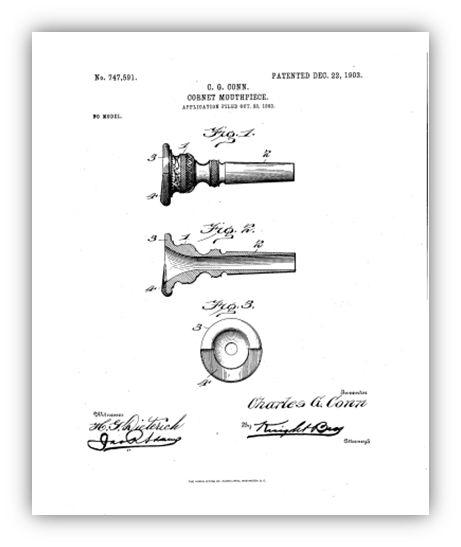

Charles Gerard Conn got into the instrument manufacturing business as the result of some drunken fisticuffs. That’s the generally accepted version of the story, anyway. There’s little evidence to prove otherwise.

Conn had played coronet in the regimental band of the 15th Indiana Volunteer Infantry during the Civil War. Back home in Elkhart, Indiana after the war, he started grocery, baking, silver plating, and rubber stamp making businesses. He also played in a local band.

One night, Conn and his acquaintance Del Crampton got drunk in a saloon and had a scuffle outside. Crampton split Conn’s lip so badly that Conn thought he’d never play the coronet again.

Conn glued some rubber from his stamp business around the rim of a coronet mouthpiece so it would feel better on his lip. He showed it to other brass players, and they wanted to buy some. He altered a sewing machine to be used as a lathe to rout a groove in mouthpieces so the rubber would stay put, and that’s when Conn decided to start another business.

C.G. Conn Ltd. became one of the biggest instrument makers in the world. It’s now owned by Steinway.

Conn’s sousaphones became known for their high quality. Herman Conrad himself wrote a letter praising Conn’s instrument, and Conn published the letter in its magazine.

Conrad was a star, so this was like Jimi Hendrix endorsing Stratocasters.

Conn introduced a sousaphone with a forward facing bell in 1908. It was part of their new Wonderphone line. Their advertising emphasized how well this design would work in parades and marches, and it’s usually what you’ll see during college football halftime shows.

Sousa preferred the raincatcher design and continued using it for his entire career.

Pepper finally added a sousaphone to his line in 1905, but he reformed his entire company as J. W. Pepper & Son in 1910. The retail and manufacturing sections closed, and the company focused strictly on sheet music. Conn and Selmer became the biggest names in brass instruments. While Conn didn’t explicitly claim to have invented the sousaphone, their ads implied as much and stressed the improvements they continued to make. To confuse matters even more, some people called it the “Conn sousaphone” the way we call tissues “Kleenex.”

From then on, if they thought about it at all, people assumed Sousa or Conn invented the sousaphone.

Sousa did say, however, in a 1922 issue of the Christian Science Monitor that, while it was his own idea, Pepper built the first sousaphone. He added that Conn made the best sousaphones.

Still, not everyone reads the Christian Science Monitor, and the misconception continues.

Conn ran for office, winning a term in the Indiana House of Representatives and another in the U.S. House. He supported temperance, perhaps remembering his drunken fight. Del Crampton, the man who slugged him in the mouth, was one of his biggest supporters.

After leaving politics, he returned to his businesses, It’s at this point that he accused Pepper of lying about inventing the sousaphone and taking the credit himself.

Pepper successfully sued him for defamation and the judge ordered Conn to publicly apologize. He did so, blaming his behavior on his tobacco usage. His businesses floundered and he sold them off in 1915, dying penniless in 1931.

Pepper died in 1919 of heart failure. Conrad passed the following year.

On March 5, 1932, Sousa arrived in Reading, Pennsylvania to conduct the Ringgold Band in concert.

The afternoon rehearsal went well, though his voice was weak when he spoke at the dinner given in his honor. He returned to his hotel before the evening concert and had a fatal heart attack. He was 77.

Following his death, doctors revealed that Sousa had fallen off a horse in 1925 and lived the last nine years of his life with a broken neck.

In 1973, a 24-year-old tuba player named John Bailey joined his mother and sister for an afternoon visit to Renninger’s Antique Market in Adamstown, Pennsylvania.

He spotted a tarnished raincatcher sousaphone hanging from the rafters. When he learned it was only $50, he rushed home for the money, thinking he found a cool old horn to play in parades.

As he cleaned it, he found it was unfinished brass, and he discovered etchings near the bell.

There was a portrait of Sousa in his 1894 uniform, the words “Sousa” and “phone” in floral ribbons, the words “J.W. Pepper Maker,” and a serial number that places it in 1895. That’s three years before Conn introduced theirs.

Bailey knew he had something special but, as a recent college grad, he couldn’t afford to have it professionally restored. So he stored it away for 17 years.

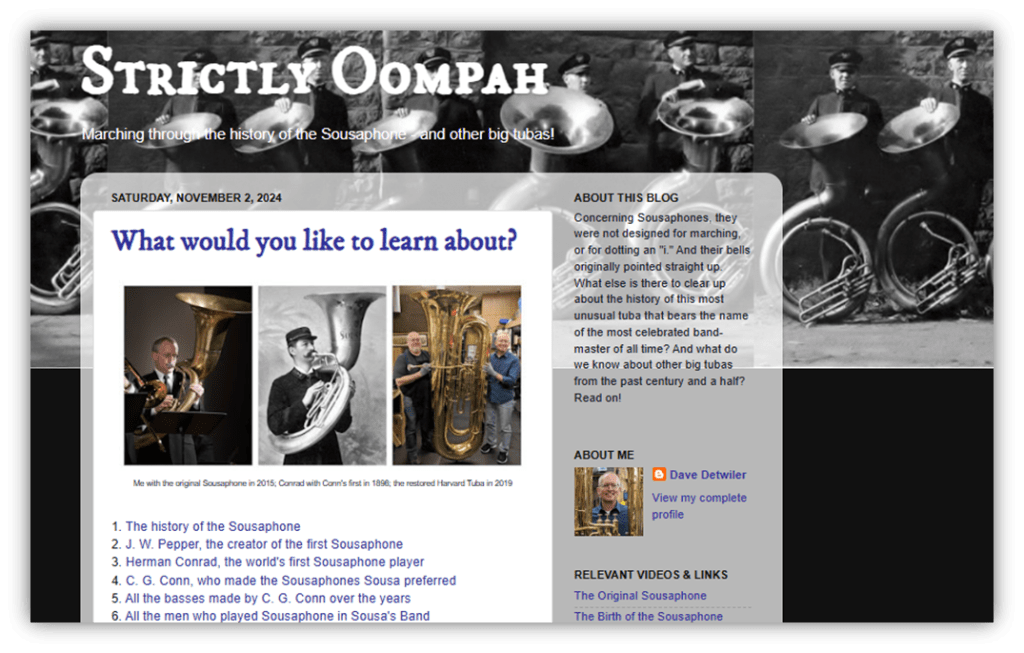

In 1991, he sold it to J.W. Pepper & Son. They had it repaired and finished, and offered Dave Detwiler a chance to play it publicly with the Montgomery County Concert Band. Detwiler is a pastor, tubist, and sousaphone historian.

He’s the one who researched most of the info in this article and proved that Pepper built the first sousaphone. If you’d like more detail about the history of tubas and sousaphones, check out his Strictly Oompah blog.

The J.W. Pepper & Son company still thrives and has almost 800,000 sheet music titles available. The original sousaphone is now in a display case in the headquarters in Exton, Pennsylvania.

Every year, tuba, euphonium, and sousaphone players get together to play Christmas carols in an event called TubaChristmas. You haven’t lived until you’ve heard “Carol Of The Bells” performed by 100 tubas.

To find a TubaChristmas near you, visit https://tubachristmas.com.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Hey, friends,

Apologies to Bill and everyone for the late start today. A surprise bout with Covid got in the way of things.

Not sure that I wanted to give that a thumbs up, but there’s no “care” option. Hope you’re feeling better soon.

Yeesh, that’s a fine Happy Thanksgiving, isn’t it? We’re thankful for all the work you put in here making this site a great hang. Now go get some shuteye!

No need to apologise. Totally understandable. Take it easy this weekend, no sousaphone practice for a while.

Ouch! Hope you get past the fever point quickly!

Fistfights, commercial skullduggery and a happy ending. The sousaphone has it all.

Has a sousaphone appeared on any #1 hits? Top 10 even?

Good question. Fleetwood Mac’s “Tusk” got to #8 on Billboard and had a marching band. I’m pretty sure it had a sousaphone or three.

That is a great answer. It looks like there are 4 of them in the official video. https://youtu.be/ATMR5ettHz8

The Roots have a sousaphone and tuba player- Tuba Gooding Jr.,

but they do not have any top 10 hits, so they don’t qualify as an answer to your question. The highest they got on the Hot 100 was #34.

According to MusicVF – who I’m pretty sure use Joel Whitburn’s pre-Billboard research – Sousa had two Number Ones – and twenty Top 10 hits! – including this bangin’ version of “In The Good Old Summertime” from 1905!

Sousa’s recordings never featured the entire band – they wouldn’t fit in the studio – but there’s certainly some tuba-like sound in the mix… it might be a Sousaphone!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3_NP9TqT68

Ah, TUBACHRISTMAS. ‘Tis really the season now.

My little town of Wilmington, Ohio, has featured a TubaChristmas every year during its community holiday show. 🙂

I’ve ordered sheet music from J.W. Pepper more than once. A fine company.

He’s a pepper…

I could say this was tubular, but that would sound dismissive … 🙂

This was a great article, Bill, and it even had a personal resonance for me. My family moved from Chicago to South Bend in 1979 because my dad got a job in computer processing with W.T. Armstrong in Elkhart, Ind. A few years later, Armstrong (a flute maker) was bought out by Conn and, by decade’s end, both fell under the banner of United Musical Instruments. My dad continued to work for UMI until his retirement in 1992.

“After the 1896 tour, the first sousaphone seems to have gone missing.”

But…just…how?

I’m sorry I missed this last week. This was way more interesting than I expected.