This new series is about things that made music better, and the people who created them.

Installments will be intermittent, subject to how much research each one takes. A lot of these folks aren’t household names so tracking down details can take time, but each made significant contributions to how we make and enjoy music.

You’ll notice that this is installment #2:

Because I’m counting my Theoretically Speaking article on Guido d’Arezzo as the first in this series.

He basically invented sheet music.

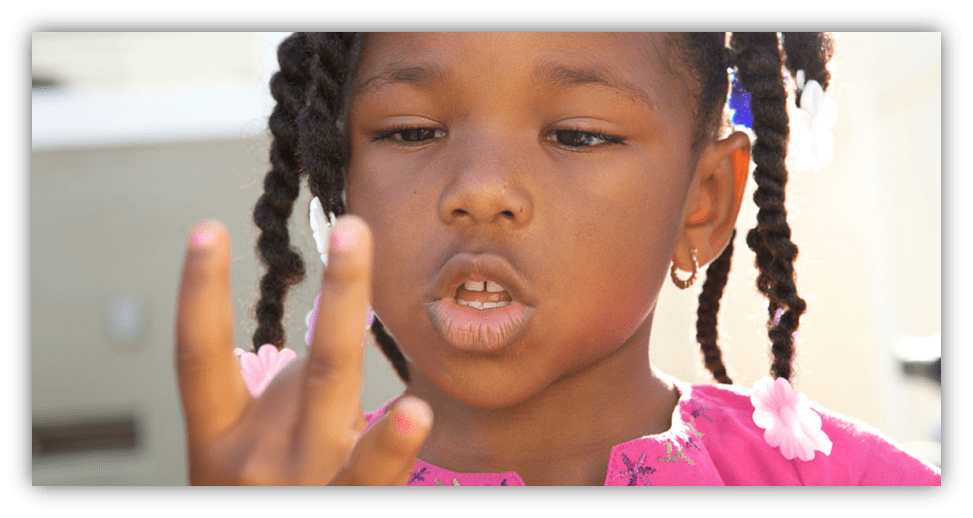

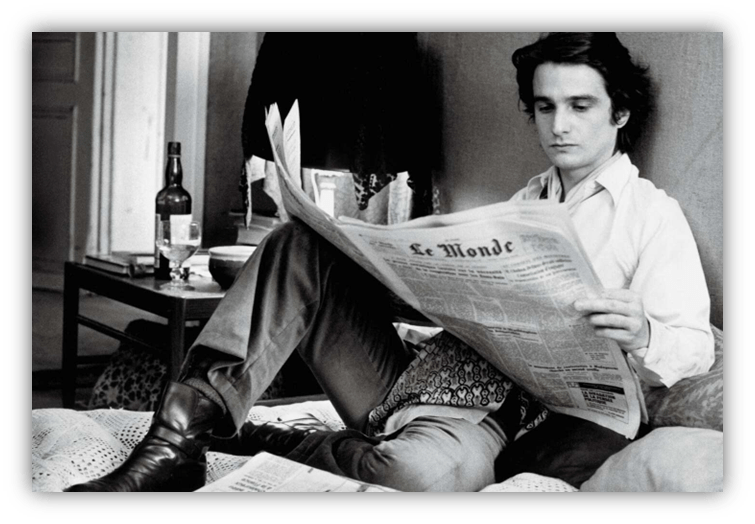

With all that in mind, let’s meet Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville:

Who we think is the first person to record sound.

He was a Frenchman of Scottish descent, living in Paris and working as a printer and bookseller. He was also a stenographer, an expert in shorthand, and had an interest in science.

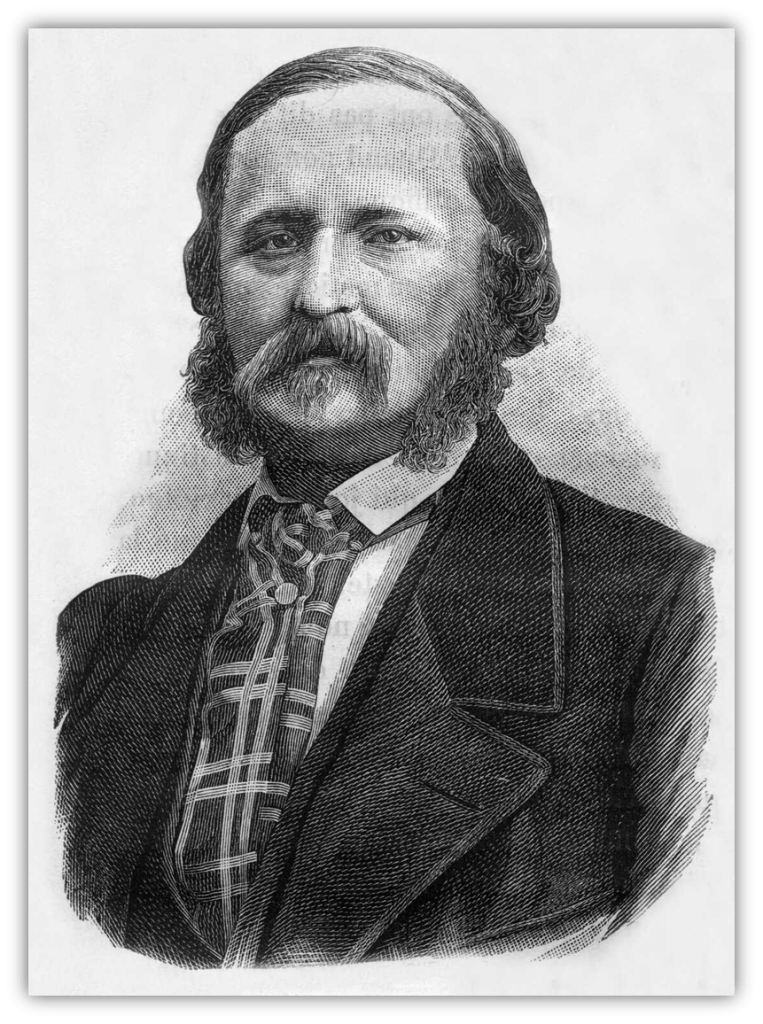

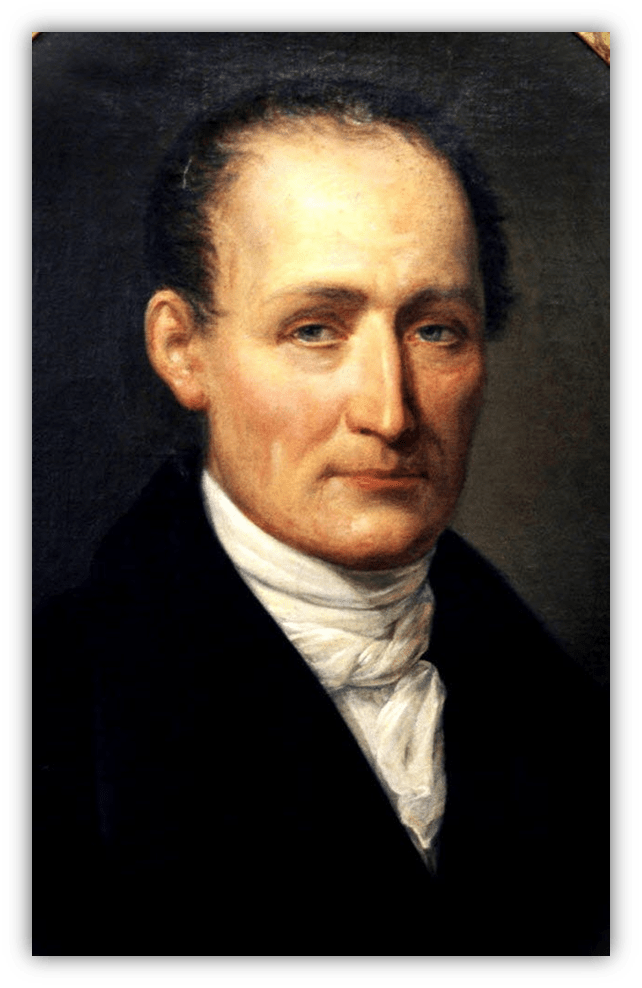

We need to start in 1822, when Nicéphore Niépce invented photography.

Working in La Gras, France, he and his brother Claude also invented the internal combustion engine, so he was no dummy.

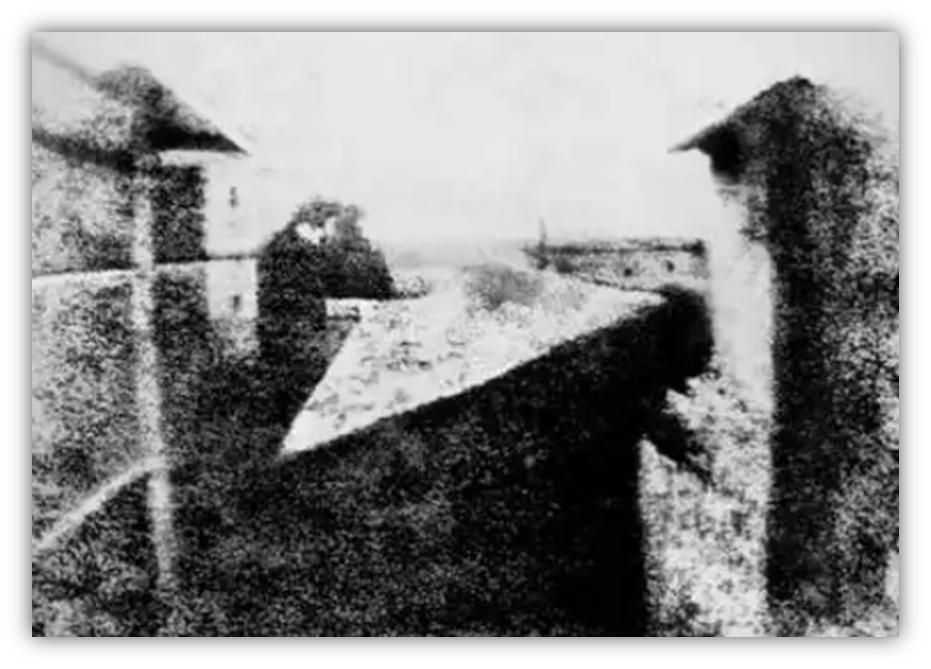

The oldest surviving photograph we have is called View from the Window at Le Gras, taken from his workshop’s window.

Niépce’s early technique was difficult and unstable, but he created a partnership with Louis Daguerre to improve the process.

Niépce didn’t live long enough to see the result, dying suddenly of a stroke in 1833. Daguerre continued working, eventually perfecting, and naming after himself, the daguerreotype. Unable to find private investors, he sold the invention to the French government for lifetime pensions for himself and Niépce’s son. France then released the technology as a gift to the world.

That was in 1839, and it was global news. Scott knew about it, of course, and it’s part of where he got the idea to do with sound what Niépce and Daguerre did with light: to capture it and put it on paper.

The other part of his inspiration was a book on human anatomy. The publishing house where he was an editor and typographer specialized in science textbooks. While looking at an illustration of the inner ear, he wondered if he could create a device that would capture sound in the same way.

The eardrum vibrates with sound waves and our brains understand those vibrations as sounds. Scott imagined a vibrating diaphragm that would transform speech into print, into something we could read.

Scott experimented with a few techniques and came to use an elastic membrane to collect sound vibrations the way an eardrum does.

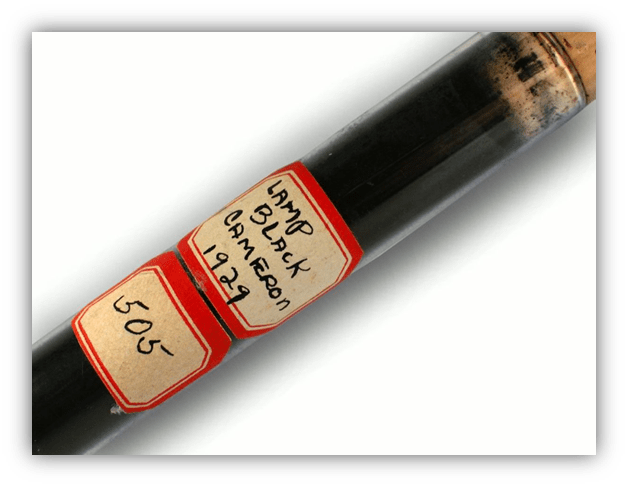

The vibrations shook a boar’s bristle, which was thin but stiff. It resembled the phonograph needles that would come later. He called it a stylus, and it etched the sound waves into a layer of lampblack on a sheet of glass as the glass moved horizontally beneath it.

He eventually switched from glass to paper. Lampblack is, basically, a form of soot.

It’s carbon material leftover after burning tar or ethylene. It’s liquid enough to be applied to surfaces, like glass and paper, but solid enough to hold its shape after being etched.

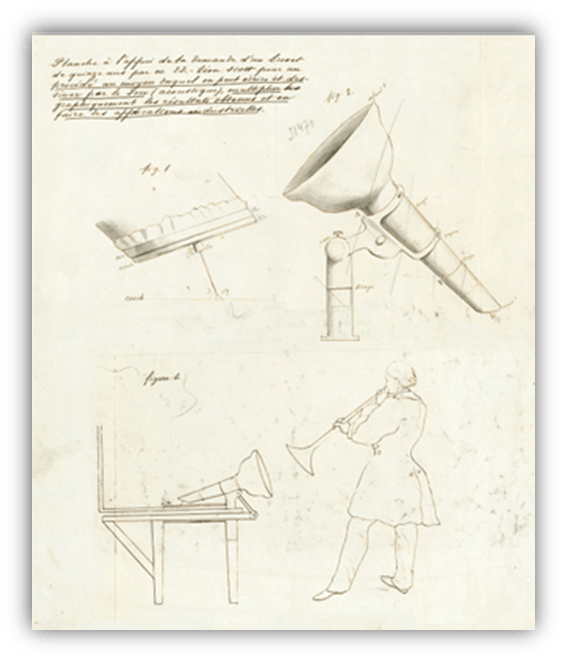

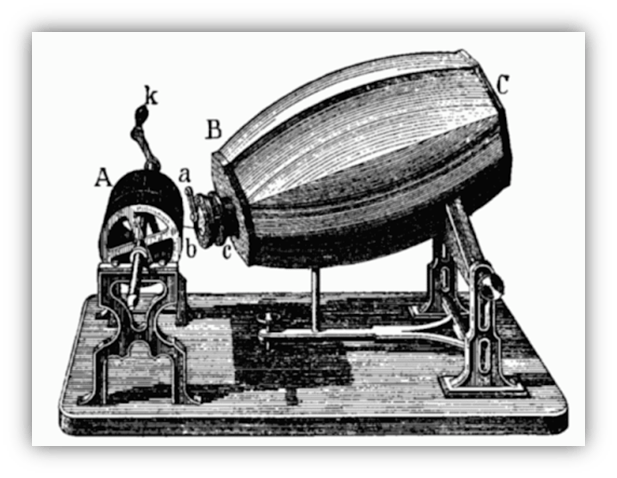

His machine worked. He called it the “phonautograph,” from the Greek words meaning “sound,” “self,” and “writing.”

The phonautograph was able to etch soundwaves that could be seen. Reading them was another matter, but Scott believed he could learn to read these waves and understand what words they represented, like he could with shorthand.

It had its limitations, as new inventions always do. Glass panes and sheets of paper can only be so long, and phonautograph moved them at a meter a second as the stylus etched into them. That meant the recordings had to be very short, maybe not even the length of a complete sentence.

Scott patented the phonautograph in 1857.

The Société d’encouragement pour l’industrie nationale (SEIN) caught wind of it and became interested. SEIN’s mission was to evaluate new technologies and estimate their potential uses in French industry.

With their input, Scott changed the pane of glass to a rotating cylinder. Cutting a single spiral groove around the outside of the cylinder lengthened the recording time from a few syllables to about twenty seconds. Thomas Edison, a couple decades later, would use the cylinder design in his invention of the phonograph. We’ll get to him in a future installment.

Reading the sound wave etchings, Scott eventually concluded, was impossible.

We know now that while the phonautograph was a failure when it came to the shorthand Scott hoped for, it helped move acoustical science ahead.

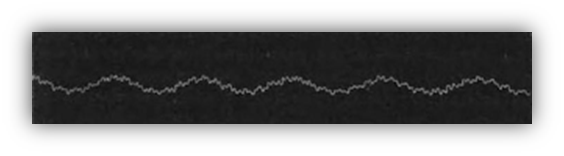

For the first time, scientists could see what they heard. They couldn’t, however, hear them.

But we can.

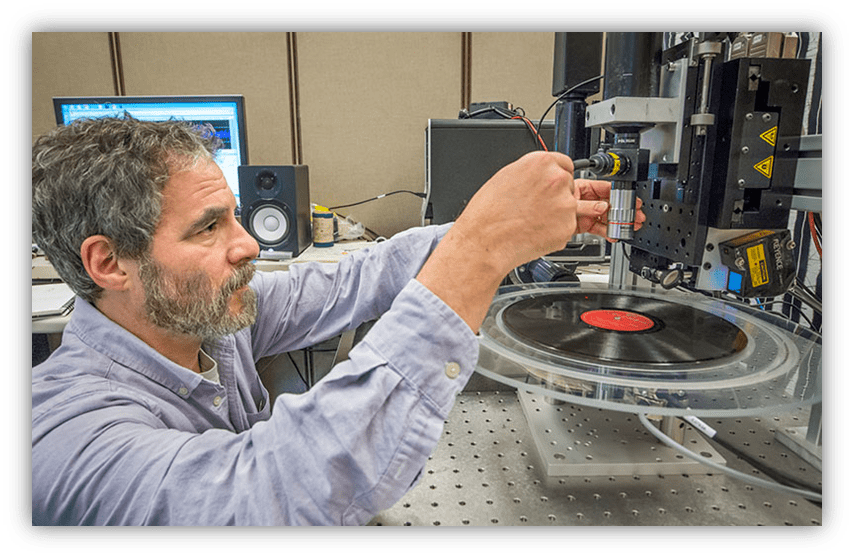

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory created virtual stylus technology under the name Project IRENE, which stands for Image, Reconstruct, Erase Noise, Etc.

It’s also a tribute to the classic song “Goodnight, Irene.” The virtual stylus uses optics to read record grooves without actually touching the record. Very old and rare recordings can be digitized without wear and tear.

In 2007, a group of scientists started the First Sounds project and used IRENE to digitize Scott’s recordings.

This worked to some extent, but some of the original recordings were experiments to see if the phonautograph’s concept would work at all. Sometimes the etch goes off the side of the paper, and sometimes the cylinder rolled backwards. It was a brand new process and there were bound to be glitches.

Over the next couple years, they improved their software to deal with the glitches and speed issues.

It turns out that Scott not only spoke, he recorded himself singing, too. The folk song “Au Clair de la Lune” was a favorite of his.

Though Scott gave up on the phonautograph and moved on to different ventures, others took the idea and ran with it. Without the phonautograph, there might not be a phonograph, or tape recording, or recording studios, or the digital audio workstations on every musician’s computer. It’s fitting that the very science of acoustics that he helped start was used to bring his recordings to our ears.

Scott’s recordings are now available on YouTube. This video has two versions of the same recording of “Au Clair de la Lune.” The second one has been tuned and de-noised.

It’s not a toe-tapper, or a million seller.

But it’s where everything started.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Of all the things one could choose to freeze and capture for the ages, who wouldn’t choose a tune hummed while gargling mouthwash? 😃

Very interesting! And a great start to the new series. Thanks Bill.

I was thinking the first effort was Au Clair de la Lune performed by the medium of buzzing fly.

I was looking Fourier good wave analysis joke, but I couldn’t find one…

That name rings a Bell.

I would chime in with a comment, but I am in the middle of trying to get some Fast Transport to my hotel.

Regardless of the vocal deficiencies and sound quality you’ve got to start somewhere. I didn’t realise recorded sound went back quite so far and had never heard of him.

Without Scott we may never have enjoyed Sgt Pepper, Rumours, Purple Rain, Disco Duck or The Macarena.

Nice job Bill on bringing his name to light.

All inventions can be used for good and evil.

I’ve read about this guy before and I may have even listened to these audio cuts. Incidentally they were #1 on the charts for a good 20 years or so.

I really look forward to this series, Bill. I’m wondering about Les Paul? Moog? Probably a lot of other people that I’ve never heard of. Very cool stuff. 🙂