Think of all the microphones you use daily.

If you’re reading this on your phone, you have a microphone in your hand.

If you’re on a laptop, there’s one there, too.

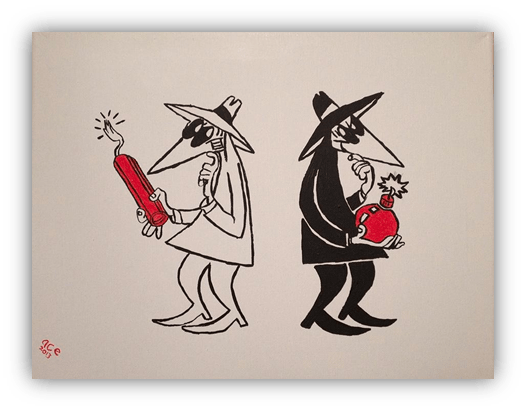

With every phone call or Zoom meeting, you use a microphone. That’s to say nothing of the various microphones around your house in smart speakers or Amazon Dots or the bugs hidden there by a mysterious spy agency.

Not that you’re paranoid.

It’s easy to forget that the idea of transmitting a voice from one place to another was a fantasy only 150 years ago.

Before then, the idea of speaking into a device in one town and being heard in another was mind-boggling. It would require the invention of both the microphone and the speaker, as well as miles of wire and Alexander Graham Bell’s genius.

The next idea was to speak into a device, store what you said, and listen to it later and possibly elsewhere. It’s a staggering thought. Or at least it was. We do it all the time now, especially with music. And for that, we can thank Edison for inventing the phonograph.

However, both the telephone and the phonograph needed improvements, and they were given those improvements with Emile Berliner’s brilliance. He was crucial in perfecting both the microphone and recording sound.

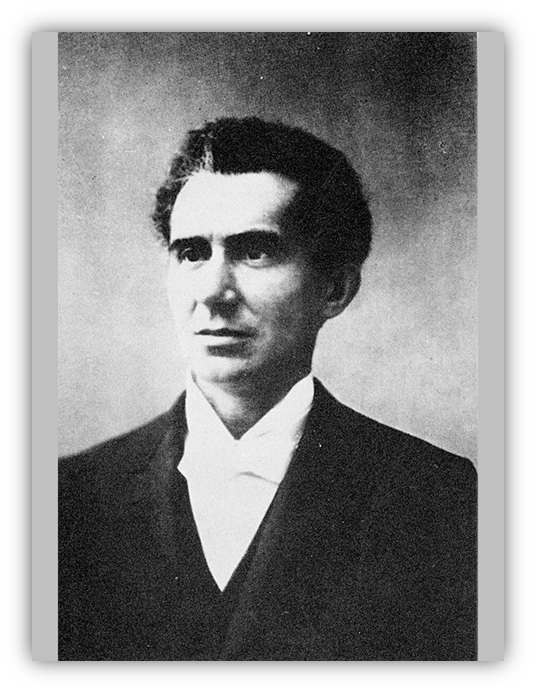

Bell and Edison are famous for their inventions. Berliner was their contemporary, collaborator, and competitor, but is not as well known. Still, he played an equally crucial role in the development of modern communication technology.

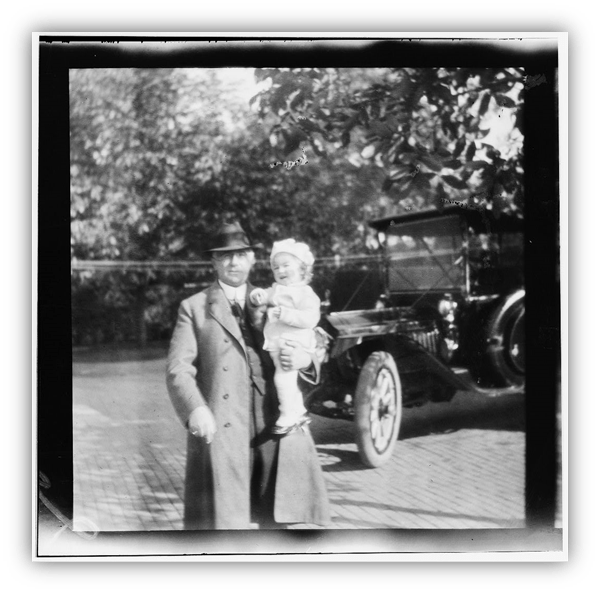

Berliner was born on May 20, 1851, in Hanover, Germany.

He showed an early interest in science and engineering but, as the son of a merchant, his formal education was limited.

Seeking better opportunities, Berliner emigrated to the United States In 1870. Initially, he worked various odd jobs while attending evening classes at the Cooper Union Institute in New York City.

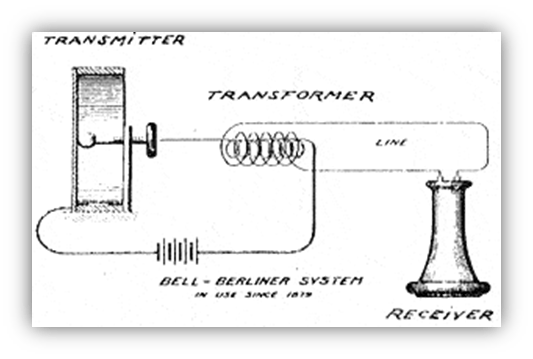

In 1877, he sold the rights to his induction coil microphone to the Bell Telephone Company, ensuring that his technology would be widely adopted. The telephone was still in its infancy, and one of its main challenges was the clarity and volume of voice transmission.

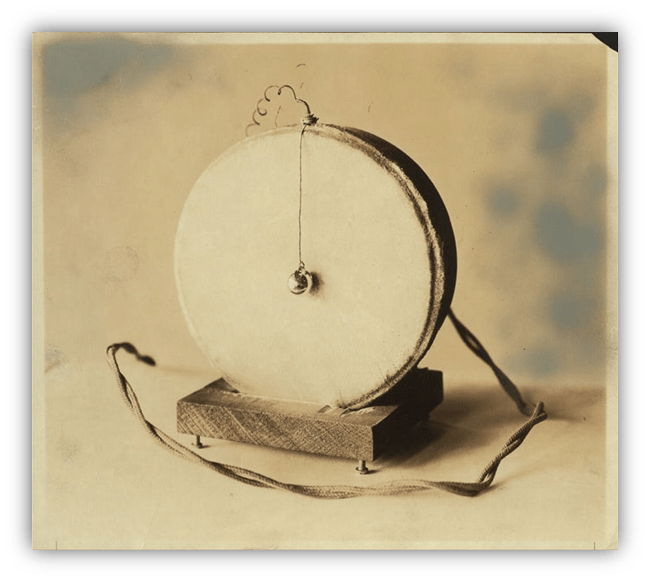

The induction coil used a magnet and a vibrating diaphragm to convert sound waves to an electrical signal. It was better than Bell’s liquid transmitter but still not optimal.

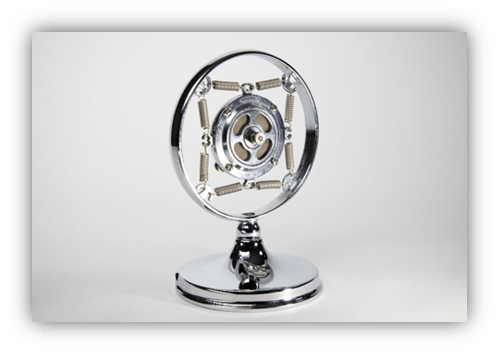

Berliner’s first major breakthrough came when he invented the loose-contact carbon microphone. It significantly improved the sound quality by using carbon granules that varied in resistance when compressed by sound waves.

These particles were placed between the diaphragm and a metal contact, and acted as a variable resistor.

When sound waves hit the diaphragm, it vibrated. The vibrations put pressure on the carbon particles, packing them together more tightly.

With all that contact between the particles, the electric current had less resistance and could pass through to the metal contact more easily. When the sound stopped, the vibrations stopped, and there was less pressure on the particles, and therefore a higher resistance against the current. He received a patent for the design in December 1879.

Berliner immediately refined the idea and received a second patent for the spring carbon rod microphone in March 1880.

The improvement here was to use a spring to hold the carbon rod or rods in place. This made for a more consistent current passing through the microphone.

These methods converted sound into electrical signals more effectively than previous designs. They were crucial in making the telephone practical and marketable.

His microphones made modern audio transmission possible, not just in telephones but also in broadcasting and recording. As I mentioned in my Theoretically Speaking article about Crooning, many of the biggest names in 20th century music wouldn’t have been stars without Berliner’s microphone. We could argue that someone else might have improved the microphone.

But without Berliner’s work in the 1870s, we might not have had Rudy Vallee in the 1920s, Bing Crosby in the 1930s, or Frank Sinatra in the 1940s.

While Berliner’s microphone revolutionized voice transmission and, later, music, his invention of the gramophone had an even bigger impact on the world of sound recording and playback.

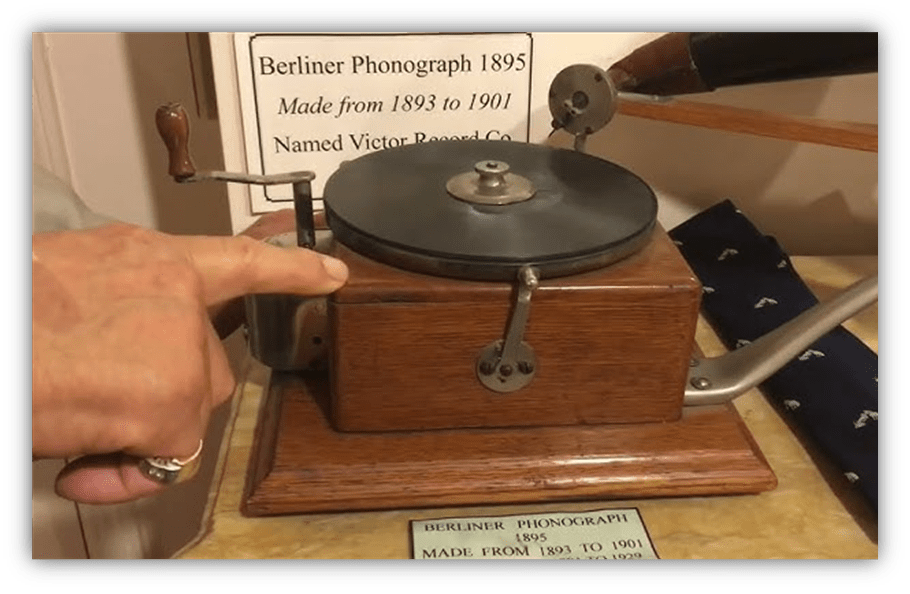

In 1887, Berliner developed the first flat disc record and player.

Unlike Thomas Edison’s phonograph, which used cylindrical records, Berliner’s flat discs were easy to mass produce, store, and distribute.

Where the cylinders had to be molded, discs were pressed. It’s a much quicker and cheaper method. Also, discs could have recordings on both sides, meaning consumers could get two songs per purchase. Eventually, they grew to 12 inches, so each side could have several songs.

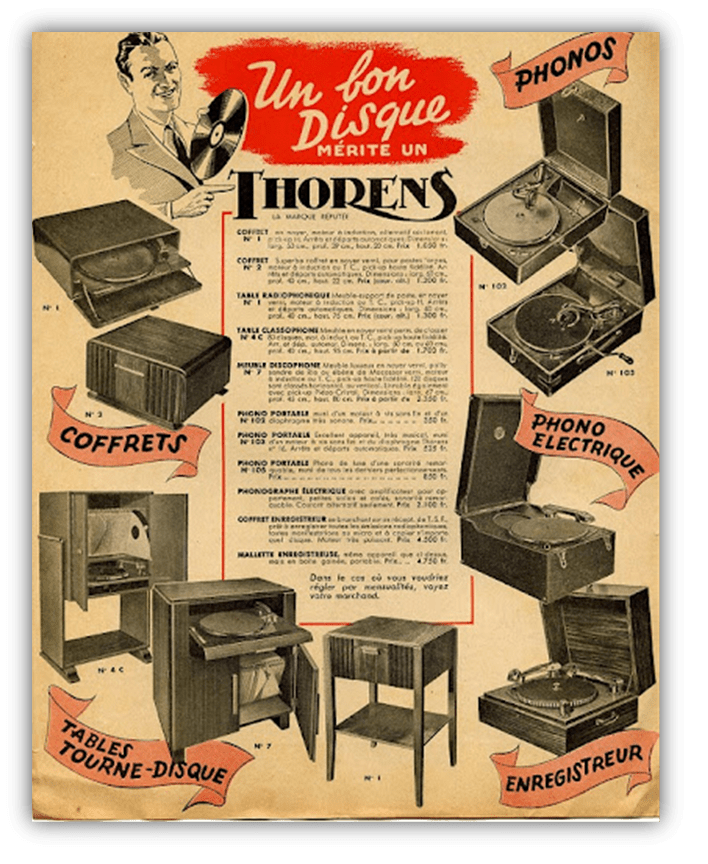

The flat disc record and the accompanying gramophone quickly became the standard for the recording industry, paving the way for the mass production of recorded music. The disc format eventually passed cylinders in sales and became the dominant medium for recorded music until the invention of the compact disc a century later.

Another problem with cylinders was there was no standard size, groove type, or speed. If you had an Edison phonograph, you could play Edison cylinders, but there was no guarantee that cylinders from other companies would work.

After Berliner, a flat disc would play on any manufacturer’s player, especially after the Swiss company Thorens introduced the variable speed turntable.

Berliner’s gramophone records could capture and reproduce sound with deep fidelity, bringing music into homes around the world.

Interestingly, Berliner coined the word “gramophone” by reversing the syllables in “phonograph.”

He trademarked the word and started gramophone companies in the United States, Canada, England, and his home country of Germany.

Like Edison and other inventors, Berliner’s curiosity led him into other fields. He advocated for improving the sanitary conditions of milk production, especially the importance of pasteurization to prevent diseases.

He published several books on the subject, including The Milk Question and Mortality Among Children Here and in Germany: An Observation in 1904.

And, in 1919, a children’s book called Muddy Jim And Other Rhymes: 12 Illustrated Health Jingles For Children. His efforts helped establish higher standards for food safety and public health.

Later, along with his son Henry, he conducted pioneering work on helicopters. They developed early models of vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) aircraft. Although their prototypes weren’t what we’d call truly successful, their research and experimentation helped others eventually develop practical helicopters.

Emile Berliner’s carbon microphone remains a fundamental component in audio technology, while his gramophone and flat disc records revolutionized the music industry.

Additionally, his advocacy for public health and his pioneering work in aviation demonstrate his diverse interests and contributions.

Despite his significant achievements in multiple fields, Berliner did not always receive the recognition he deserved during his lifetime.

However, his legacy endures each time we use one of the technologies he pioneered.

Museums, institutions, and historical societies honor him as one of the great inventors and industrialists of the 19th and 20th centuries.

To say nothing of those double album covers, which were great for rolling joints.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Donut take Berliner for granted. Those who do are just jelly!

Great stuff, Bill. Happy Friday!

Ha! And now I want a croissant.

Fun fact, Berliner was also responsible for Nipper the dog’s image being used on records.

Emile definitely deserves to be better known. Thanks for bringing him and his myriad exploits to light.

Out of his whole portfolio the one that most grabbed my attention was his health jingles for children. It speaks to me that he’s a guy who didn’t know how to relax and take it easy.

I wouldn’t say he had a way with words, they don’t scan well but he gives very sensible advice (apart from that one where he advocates the health benefits of joining the army). He was way ahead of the curve on nicotine. Though I’m not sure such many kids would have been enamoured to receive a book of his sober jingles.

You can see the full book here; https://www.loc.gov/resource/berl.04010600/?st=gallery

I learned several new things today – thank you!

I really like this series.

When you read a good period piece, you can feel the awe of the invention, no matter how outdated, through the language of the omniscient narrator and the dialogue that his characters utter. Great article, V-dog. It reminded me of the novel Two Moons by Thomas Mallon. The main character, an astrologist, is in awe of the phonograph. There are two astrologists. The phonograph captures all this banal conversation. Nothing of importance, you think. But then, one of the astrologists die, the male astrologist. To remember him, the female astrologist plays a brief recording of his beloved on Thomas Edison’s invention.

“Honey, I’m home.”

That’s how the novel ends.

Oh, god. I’m tearing up now.

The art of literature.

The freedom to write.

I change my “What’s Good” grade to a 8.

(I like old movies because the rotary phone is visually arresting. Recently, I clapped like a total dork watching Clint Eastwood use a pay-phone in Blood Work.)