I was in a Punk band in the 1980s when the three rules of the day were:

Faster. Faster, and Faster.

It was a badge of honor to be the fastest band in town.

It’s why Hüsker Dü named their live album Land Speed Record.

For a while, DRI were considered the world’s fastest band.

But it got to be a matter of opinion when the beats became a blur. None of us wondered if we were playing too fast. Too slow, maybe…

But too fast? There was no such thing.

In most genres of music, however, the goal is to play at the right tempo without speeding up or slowing down. Non-musicians might think that’s easy.

But it can be really difficult to maintain a constant speed, especially in a live setting when your adrenaline starts flowing. It’s even harder with slow tempos.

So when musicians practice, we often use a metronome as a tool.

It helps us learn to feel what it’s like to play at a consistent number of beats per minute. The regular tick tock eventually becomes ingrained, and good musicians – especially rhythm instrumentalists like drummers, bassists, and rhythm guitarists – learn to feel where those tick and tocks are without a machine to help us keep track.

I obviously need to practice more.

Just follow along.”

The metronome isn’t a musical instrument, but musicians use it in training. Its invention changed how composers wrote music. That leads us to two questions.

- Who invented it?

- And did he get the credit he deserved?

There is no historical evidence that Dietrich Nikolaus Winkel and Johann Nepomuk Mälzel ever met in person.

They knew about each other, and had a lot in common. They were both born in Germany, Winkel in Lippstadt and Mälzel in Regensburg, in the late 1700s. Both moved to nearby European capitals while in their 20s. And both had mechanical and musical skills, and would combine those two interests throughout their careers.

We really don’t know much about Winkel.

He was born around 1777 but how he learned mechanics and music is a mystery.

After moving to Amsterdam, he made his living as an instrument maker and was dedicated to solving practical issues in musical performance and practice, particularly those having to do with tempo and rhythm.

There’s much more information about Mälzel. (You’ll also see it spelled ‘Maelzel.’) His father was an organ builder and a skilled mechanic who likely influenced Mälzel’s early interest in both disciplines.

Mälzel received an education that included music training, but he gravitated towards instrument making and inventing.

He moved to Vienna about the same time Winkel moved to Amsterdam, and became involved in its thriving cultural and scientific scene.

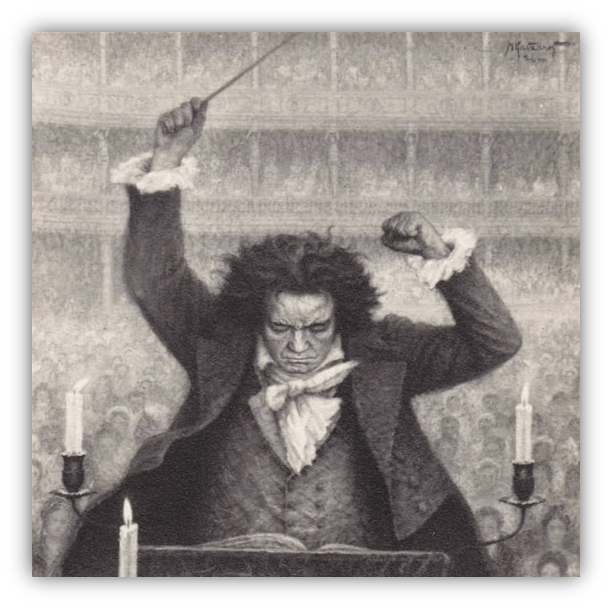

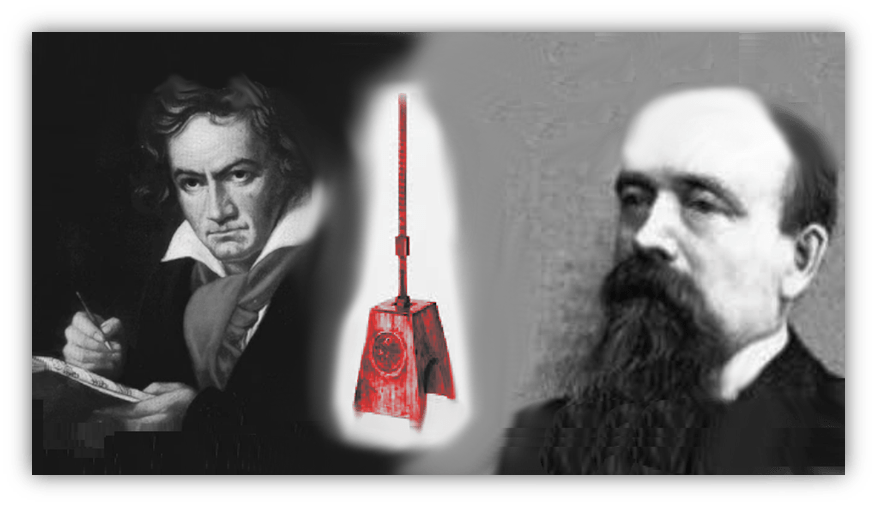

In Vienna, Mälzel’s career as an inventor began to take off with a series of innovations that drew the attention of prominent composers and musicians. Ludwig van Beethoven was a fan.

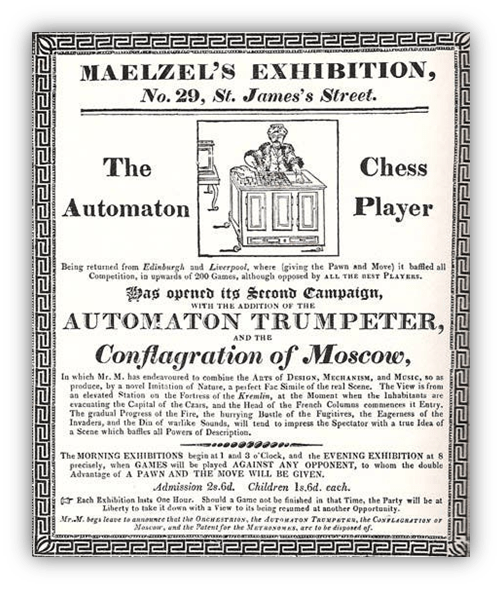

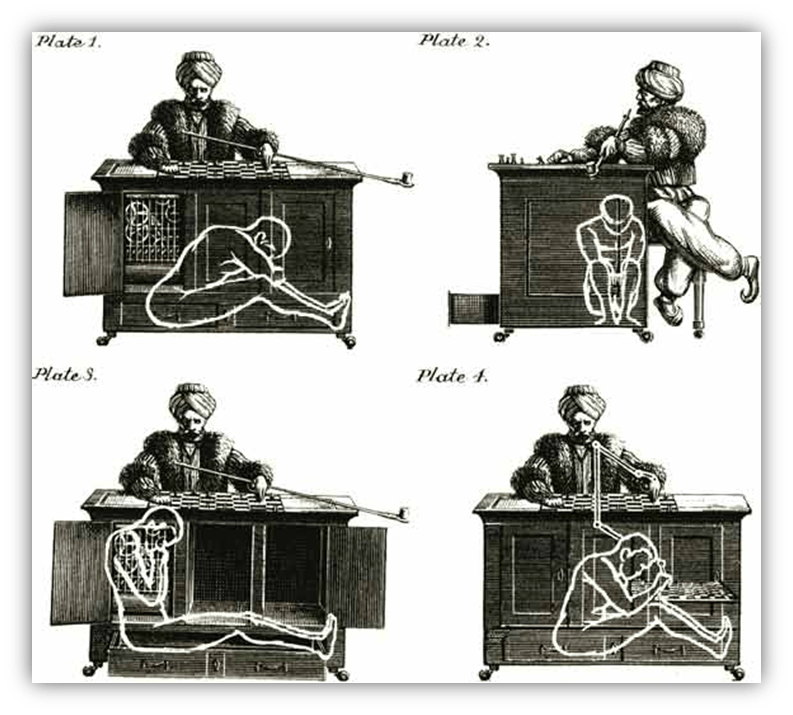

The other important thing to know about Mälzel is that he was a bit of a huckster. In 1805, he bought The Mechanical Turk, which was reported to be a chess playing automaton.

Built in 1770 by Wolfgang von Kempelen, it appeared to be a machine that could play chess against human opponents and win, but it was a fake. Its cabinet was big enough to conceal the chess expert hiding inside.

Mälzel used his mechanical skills to make improvements to the Turk and his charisma to promote a tour of Europe. The Turk was a sensation, and made Mälzel a lot of money. Even Benjamin Franklin and Napoleon Bonaparte played against it. In 1811, Mälzel sold it for three times what he paid for it.

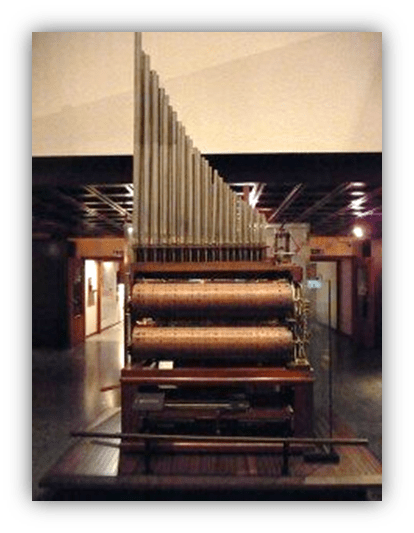

Winkel is known for two major contributions to music, the second of which is the componium.

This is a musical instrument that plays itself.

Housed in a fine furniture cabinet, its spring driven engine pumps air for an organ whose notes are played by dual rotating cylinders. The cylinders take turns playing notes for two measures, and which one plays at any given moment is chosen at random by a mechanical switch.

This means that it spontaneously composes its own music and will never play the same composition twice. Winkel was one of many people making these automatic music machines at this time.

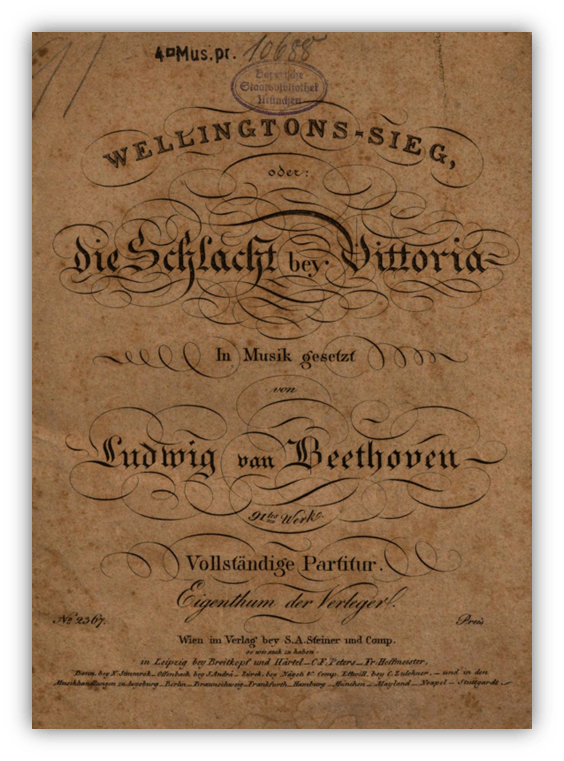

That includes Mälzel, who had made a mechanical bugler, and a device he called the panharmonicon.

It was a machine that played actual orchestral instruments, including flutes, trumpets, clarinets, violins, cellos, drums, cymbals, and triangles.

The panharmonicon attracted the interest of many people, including Beethoven. The two became acquainted in the early 1810s due to their shared interest in music and mechanical innovations.

When the soon-to-be Duke of Wellington defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Vitoria in 1813, Beethoven and Mälzel decided to mark the occasion.

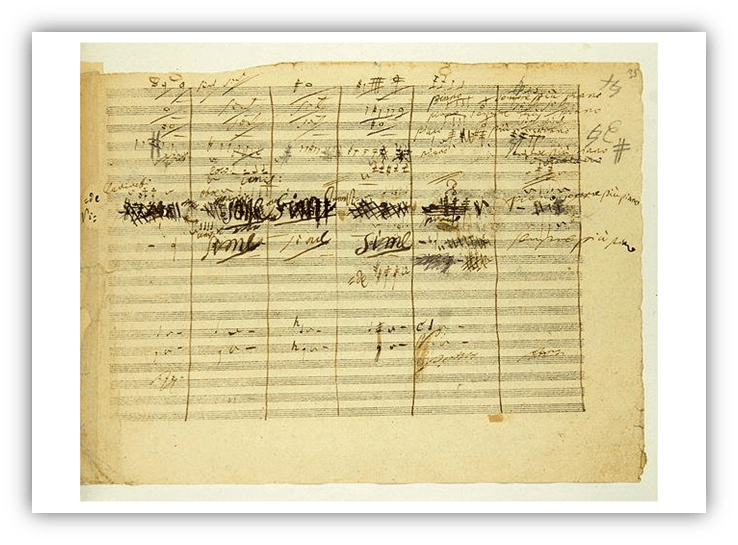

Beethoven wrote Wellingtons Sieg oder die Schlacht bei Vittoria), Op. 91, more casually called Wellington’s Victory or the Battle Symphony. And he wrote it for Mälzel’s panharmonicon, but it included more instruments than the existing model could handle.

Part of Beethoven’s enthusiasm to write the piece was because Wellington had won, and part was because Mälzel had loaned him money. Mälzel, meanwhile, had to expand his panharmonicon to meet the needs of Beethoven’s composition. While he did that, he suggested Beethoven arrange the piece for a live orchestra concert in order to raise money.

The Battle Symphony was performed twice in Vienna and the income was substantial. However, Mälzel thought the money was his because he had paid for the composition. Beethoven said it was just a loan, and the two – who each had a hot temper – had a falling out. Beethoven even filed suit.

They had planned to bring their fantastic new piece to London to make even more money, but that was called off.

However, Mälzel stole a copy of the score and started out for England. Beethoven wrote an open letter to the musicians of London to tell them not to trust Mälzel.

Realizing that working together was more beneficial than fighting, they settled. Mälzel returned to Vienna, Beethoven called off the lawsuit, and they split the money. Through it all, Mälzel assisted Beethoven with his increasing deafness by making improvements to the ear trumpet, an existing device that helps the hearing-impaired hear more clearly.

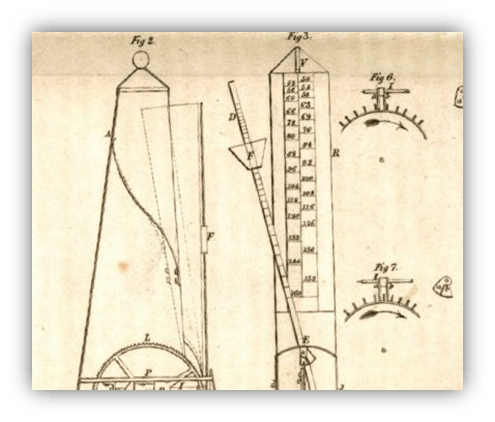

While all that drama was going on, Winkel was working with pendulums. He noticed that if a pendulum was weighted on both sides, it would swing at regular intervals.

He refined this concept into what he called a chronometer. It produced a steady pulse, or beat, which helped musicians maintain consistent timing during practice. The tempo could be adjusted but once set, it clicked at a constant speed.

However, not only did Winkel not do a good job marketing it, he didn’t even patent it. The Dutch patent system wasn’t as developed as in other countries, like Germany, and the process was tedious and expensive. Maybe that deterred Winkel, or maybe he didn’t see the commercial potential, or maybe he just wanted scientific recognition. We really don’t know.

Word got around though, at least in inventor circles, and Mälzel wrote a letter offering to buy the design. It’s hard to say why but Winkel refused the offer. And he still didn’t patent it.

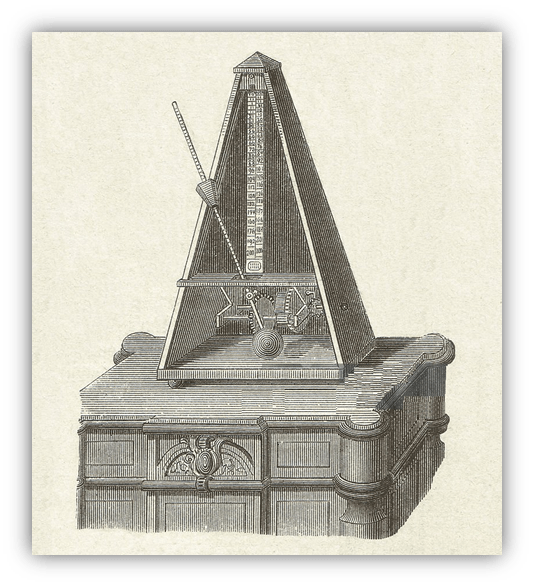

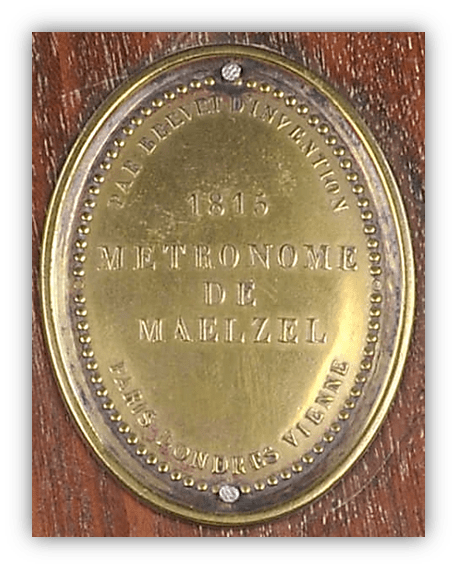

Without compunction, Mälzel improved Winkel’s design by adding a numbered scale indicating the number of beats per minute.

He patented this new design and marketed it as “Mälzel’s Metronome.” He gave Beethoven one as a gift, which was a smart business move.

Until this time, composers marked their sheet music with words, usually in Italian, to indicate tempo. “Adagio” means “slowly,” “moderato” means “moderate,” and “presto” means “very fast.” There are a dozen others but they’re all relative terms. One man’s adagio is another man’s moderato.

Once Beethoven got his metronome, he started marking his compositions with the exact number of beats per minute he wanted. Other composers bought metronomes and did the same. Conductors and musicians bought metronomes to make sure they got the composers’ desired speed right. There was no longer any uncertainty about tempo.

The metronome was a hit and Mälzel, who was already well off, made a killing. People naturally assumed, since he named it after himself, that he invented it. He didn’t dissuade them.

Winkel, understandably upset by Mälzel’s appropriation of his design, contested the claim. In 1817, the Royal Dutch Academy of Sciences recognized Winkel as the true inventor of the metronome, acknowledging that Maelzel’s device was based on Winkel’s original design. However, this recognition did little to change public perception, as Maelzel’s commercial success had already made him the name associated with the metronome.

Winkel invented other devices that improved the performance and functionality of various instruments.

He developed music boxes and other automatic musical instruments. His understanding of mechanics helped him solve complex problems related to music and sound production.

But when he died in 1826, he was relatively unknown compared to contemporaries like Mälzel. Despite the recognition he received from the Royal Dutch Academy of Sciences, Winkel’s contributions were largely forgotten. Mälzel’s commercial success outshone him.

That same year, Mälzel, who had repurchased The Mechanical Turk in 1815, took it to the United States with chess master William Schlumberger as the man inside the box. They toured all the major east coast cities. Edgar Allen Poe saw it in Baltimore and wrote an essay called “Maelzel’s Chess Player,” in which he surmised the machine was a fraud.

Many of his guesses as to how it worked were wrong, but overall he was right. The Turk was a hoax.

In 1836, they traveled to Havana, Cuba, where Schlumberger contracted and died of yellow fever. With no chess master and with his own health failing, Mälzel boarded a ship to return to Europe. He died at sea.

Though sometimes viewed as more of a showman than a true inventor, his ability to popularize innovative devices left a lasting impact on music, technology, and culture.

His partnership with Beethoven and his influence on music practice through the metronome have made him a key figure in 19th-century music and technology. While his name is most often associated with the metronome, his panharmonicon and other musical automatons showcased the potential of mechanical music.

His continued work on devices for the deaf shows a commitment to using technology to improve people’s lives.

While Mälzel may have reaped the benefits, it’s Winkel who deserves the credit for creating one of the most enduring and essential tools in music.

His chronometer, which was ultimately refined into the metronome widely used today, was a revolutionary breakthrough.

It has helped musicians achieve greater precision in practice and performance.

His life and work remind us:

Genius is not always recognized in its own time.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

“But it can be really difficult to maintain a constant speed…”

Amen to that. I never did like playing with a metronome as a kid. I once threw the metronome down the stairs in anger, while practicing the piano and getting frustrated. Its tick was uneven with its tock after that, rendering it worthless. We didn’t replace it for awhile, and I didn’t miss it, but I probably paid the price for not using one more often growing up. As an adult, whenever I had to play with a click track in the studio, it didn’t often go so well and it could take awhile to get a good take.

A good reminder today that history is not always kind to the original inventors of things. I’ll remember that every time I write a tempo marking that begins with MM=.

If only your metronome had clicked in a swing beat.

It sort of did, but not quite.

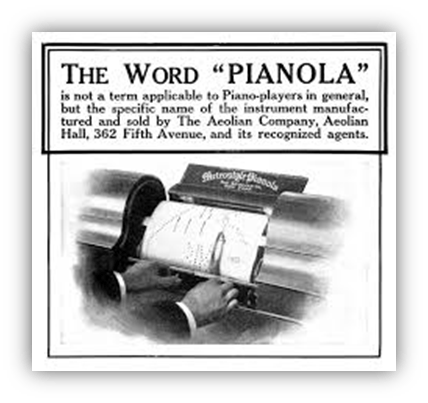

Sounds like Malzel was likely George Antheil’s hero. He too was equal parts genius and flim flam man. And he managed to synchronize a chorus of 16 pianolas and other devices for his Ballet Mechanique–yet had to fake his disappearance in order to gin up attention.

Some level of that mischievous theatricality is fine in the art and entertainment world, though admittedly I have grown both weary and apprehensive of it due to its overuse in the political realm.

Maybe some of Winkel’s descendants changed their name to Winklevoss, as their legacy seems similar. Ironic that the pilfering didn’t even require any winkling.

As Barnum almost certainly didn’t say, “There’s a sucker born every minute.” Too bad that’s true in both entertainment and politics. Even after finding out that Barnum’s exhibits were tricks, he still sold a lot of tickets, and corrupt, incompetent politicians still get a lot of votes.

That little video on the componium was awesome. Never underestimate the power of PVC pipe!

Thanks Bill for another piece of “interesting musical history that I would never have found out about except that I read tnocs.com!”

Seriously to all the article writers, this site gives me much joy. I am amazed at your knowledge and willingness to share it with the rest of us.

That is wonderful to hear, mjevon.

Thanks! That’s why I’m a reader here every day.

The amazing work of our talented writers continues to astound me.

Not withstanding: Some days, I wonder if we’re doing a good job, and if people are enjoying… whatever it is we’re trying to do around here.

You have no idea how much you just lifted me up and made my day. Thank you so much For the very kind words and participation.

Who said, “I can live for two months on a good compliment,” Mark Twain? Remember, mt, you’re the reason we’re here day after day. You’re definitely doing something right.

mt is the genius recognized in his own time.

❤️

It’s been a pleasure working with you, Mr. Twain.

I’ve never given a moments thought to the backstory of the metronome or how important it was to music but this proves there’s gold in the unlikeliest of subjects. Thanks Bill!

I naively assumed the metronome was a lot older. Or at least that a rudimentary version would have been knocking (sorry, ticking) around for centuries.

The panharmonican is fascinating as well. An automated upgrade on the one man band. A one man orchestra it seems. Are there any still in action?