We don’t know who invented the harpsichord.

It evolved into existence from previous instruments, like the psaltery and clavichord.

The best guess is the harpsichord came together in medieval Europe sometime during the 14th or early 15th century.

The earliest reference to something resembling a harpsichord is in a 1397 document by the German physician and composer Hermann Poll. He described what he called a “clavicembalum” which may have been a psaltery with a keyboard to pluck the strings.

The harpsichord was refined by various builders over the centuries and across western Europe. Hans Ruckers in Flanders and Giovanni Baffo in Italy crafted beautiful instruments and improved the instruments’ tone. By the 16th century, the harpsichord had become widely used and was particularly popular in Baroque music.

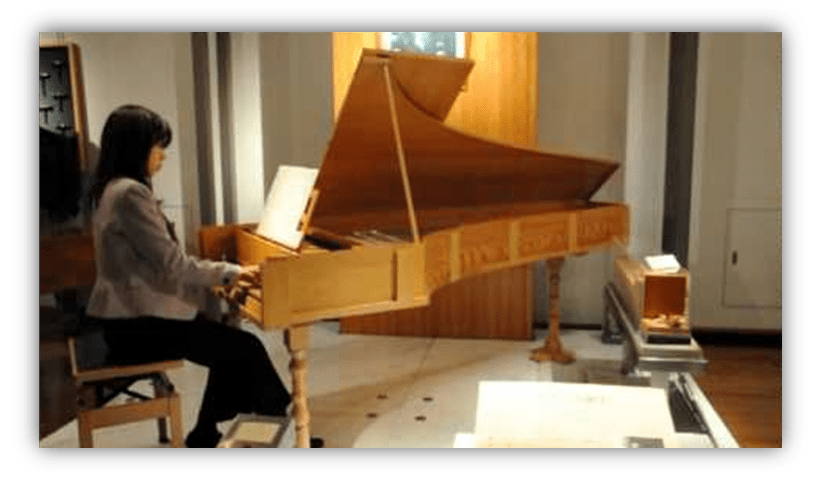

The flaw, if you want to call it that, in the design is that harpsichords play at one volume. As I mentioned in my article about Baroque, the strings inside a harpsichord are plucked.

It doesn’t matter how hard or gently you play the keys, the string is always plucked with the same force. That’s just how its mechanics work. Volume dynamics weren’t really important in Baroque music.

But sometime around the year 1700, an Italian instrument maker named Bartolomeo Cristofori thought he could come up with something better.

We have his birth and death records so we know he was born on May 4, 1655 in Padua and died on January 27, 1731 in Florence, but that’s about all we know about him. There’s almost no information about his upbringing, education, personality, or relationships.

But we do know that he was an apprentice to violin maker Nicolo Amati, the famed master luthier. (Antonio Stradivari may have been an Amati apprentice, too, though evidence is inconclisive.)

The Amati family had a long history of building high quality violins. Under Amati’s tutelage, Cristofori became a skilled instrument builder and was particularly good at making violins and keyboard instruments, though it’s likely he was already pretty good if he was able to land the apprenticeship.

The other important thing we know about Cristofori is that he was in northern Italy at the tail end of the Renaissance.

This period rejected superstition and embraced science, art, reason, and more. It was when Europe came out of the dark ages and into an era when intelligence, craftsmanship, and artistry were valued. Christofori was at its epicenter.

So we can assume that he was very skilled at his work because he was recruited by Prince Ferdinando de’ Medici to be his “Keeper Of Musical Instruments.” Princes don’t hire schlubs. They hire the best of the best.

In 1690, Cristofori moved to the prince’s household in Florence. His job was to fix old instruments and make new ones, and he was also a musician in the prince’s court.

The extensive collection of instruments he watched over included harpsichords, clavichords, and other early keyboard instruments. This was where Cristofori began to experiment with improving them. His position gave him the time and environment to create new instruments.

He’s credited with both the spinettone and the oval spinet, both of which have now fallen out of popularity.

He called his most famous instrument the “gravicembalo col piano e forte,” which translates to “harpsichord with soft and loud.” It was considered a variation of the harpsichord and was called a harpsichord for decades, so that makes it difficult to follow its history.

It eventually became known as both “pianoforte” and “fortepiano” — meaning “soft-loud” and “loud-soft” — and a 1700 inventory of instruments in the prince’s collection includes a pianoforte.

Now we simply call it: the piano.

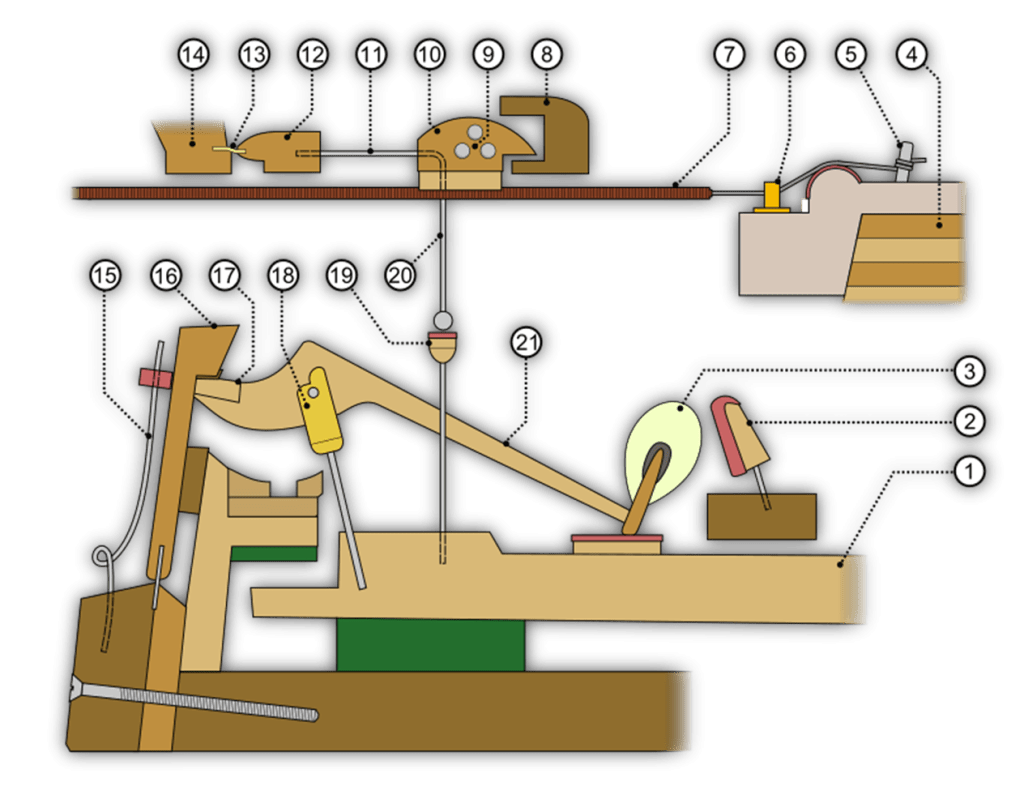

Christofori’s innovation was to replace the harpsichord’s plucking mechanisms with small hammers to hit the strings.

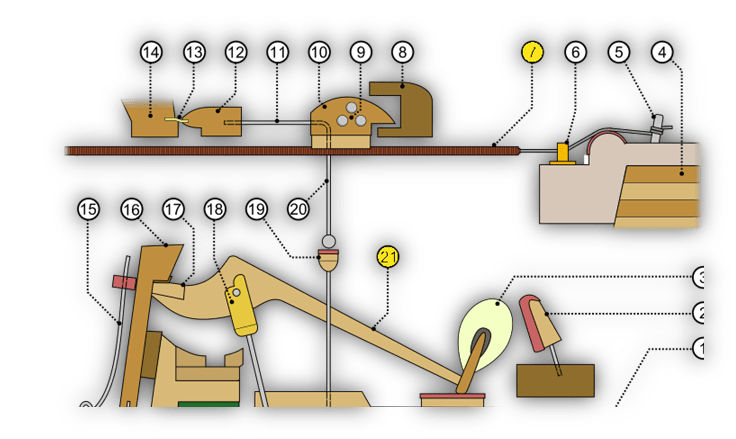

It works like so:

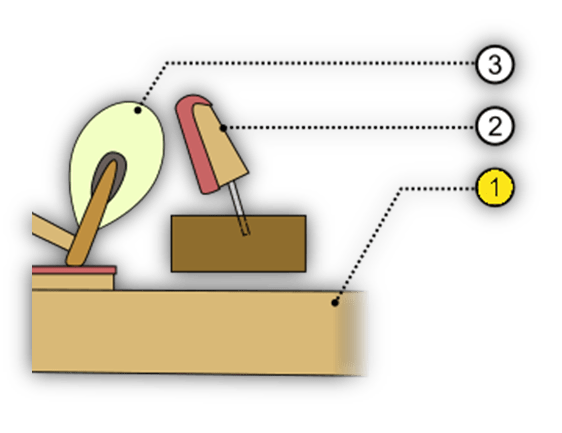

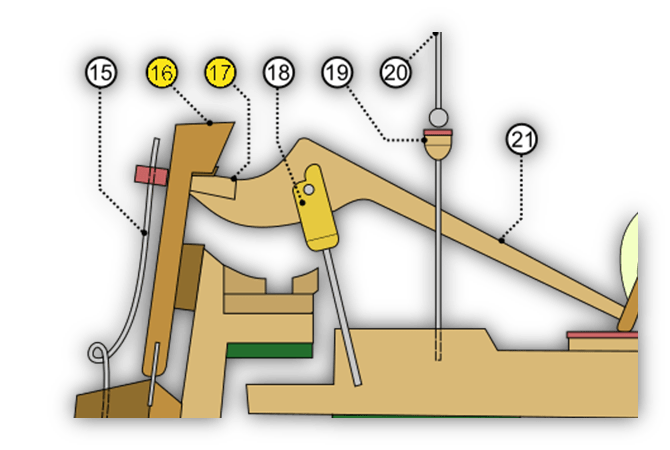

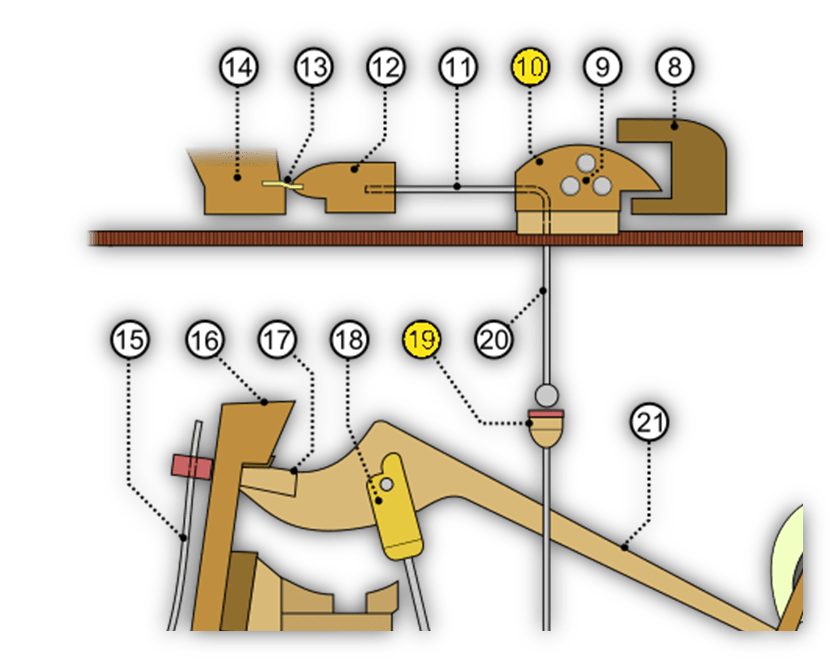

- When the player presses the key (1), its rear part is raised upwards

- Which in turn raises the slip (16) so it comes into contact with the hammer base (17).

- That moves the hammer arm (21) closer towards the string (7).

- The hammer hits the string and falls on the catcher (2).

- In the meantime, the damper lifter (19) raises the damper (10).

When the player releases the key, the damper falls back onto the string, the hammer base slides under the slip, and the key is ready for another note.

It’s a complicated apparatus, and contemporary pianos use even more complicated ones.

The hammer mechanism allowed the player to control the volume of the sound by varying the force with which the keys were pressed.

Gentle presses result in quiet notes, while harder presses produce louder ones.

Since the hammers fall back quickly after striking the string, they don’t interfere with the string’s vibration. This is called an escapement mechanism and similar devices are found in clocks and watches to keep them ticking at regular intervals.

The dampers stop the strings from vibrating when the keys are released, ensuring that the sound could be controlled more effectively.

A note will ring for as long as the key is held down, or until the string stops vibrating on its own.

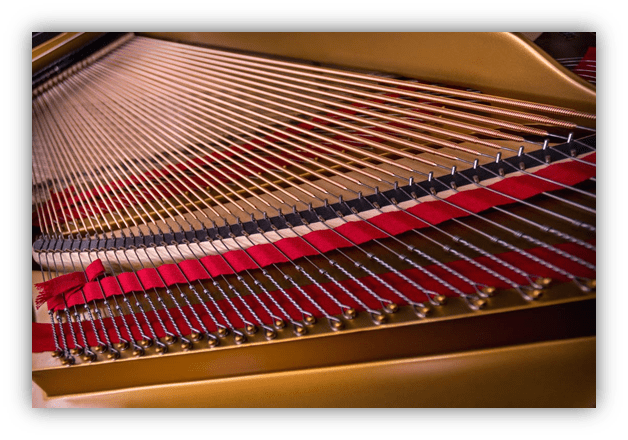

Early pianos sounded more like harpsichords than more recent models because they used harpsichord strings, made of iron or brass.

Contemporary pianos use steel wrapped with copper for the bass notes and high-tensile steel for the rest. Also, harpsichords, and therefore Cristofori’s early pianos, had only one string per key.

Modern pianos use one string for the lowest 12 bass notes, two strings for the next ten or so, and three for every note above that.

Despite the revolutionary nature of Cristofori’s invention, the early piano didn’t catch on right away. It was more expensive to build than a harpsichord and didn’t sound much different, at first. Musicians and patrons were slow to recognize its potential.

Cristofori continued to refine his design in the following years, but he did not receive widespread fame or financial success from his invention. He remained in the service of the Medici court for the rest of his career, even after the prince’s death in 1713.

However, he was able to sell instruments to people outside the court and sold instruments of all types across Europe. The King of Portugal bought a piano.

Much of Cristofori’s later work focused on improving the piano and other keyboard instruments. Some of his oldest surviving pianos, dating from the 1720s, are now housed in museums, such as the Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti Musicali in Rome and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

These pianos show how far he had developed the instrument during his lifetime.

Cristofori died without receiving popular recognition for his invention, at least not during his lifetime.

However, his piano would go on to become one of the most important instruments in Western music.

In the years following his death, other instrument makers, particularly in Germany, began to adopt and modify his design.

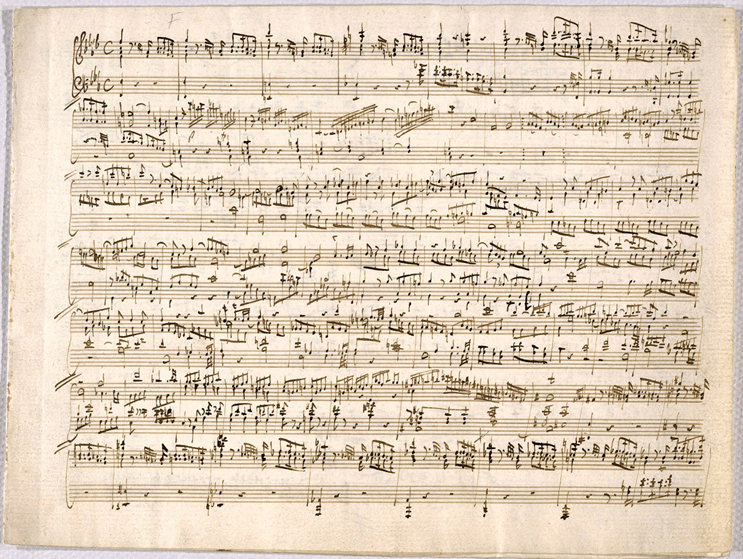

By the late 18th century, composers like Mozart and Beethoven were writing music specifically for the piano, taking advantage of its dynamic range and expressiveness.

The piano eventually surpassed the harpsichord in popularity, and became the centerpiece of classical music performance and composition in the 19th and 20th centuries.

That’s to say nothing of its use in Ragtime, Jazz, and the Rock & Roll of Little Richard, Fats Domino, and Jerry Lee Lewis.

Cristofori’s piano laid the foundation, not just for its own evolution, but for all the wonderful music written for it.

Today, his handmade instruments are treasured relics that show his brilliance, creativity, and craftsmanship.

Though he may not have lived to see the full impact of his invention, and though we know next to nothing about him, he’s truly important in the history of music.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

It wasn’t even that long ago that I first learned the origin of the name piano. I saw “pianisimo” on a score in YouTube and wanted to know what it meant.

And then I was confused. “Very softly?” Why does piano mean soft when it can be played loudly as well as softly?

Wha–“pianoforte?” Ooooohhhh….

**mind blown**

Language mutates so easily that we sometimes lose track of original meanings. One could say that forgetting context is a cake walk, but I will refrain from doing so for historical reasons.

Glad that Mozart got some props. He must have had invested in pianoforte stock, because so many of his works were centered on showcasing the beauty that its dynamic range can provide.

Here’s some inspiring Friday listening!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OsUeKnqWf50

As fast as language moves, technology moves faster. That’s why we still say we “dial” our phones.

Beautiful Mozart piece!

I actually knew the original name for the instrument because of my deep love for 19th century British literature which often describes playing the pianoforte as a popular evening entertainment in prosperous households.

Bravo Bartolomeo! Not forgetting Bill.

That explanation of now a piano works took what I naively had never really thought about but assumed would be quite simple and taught me its actually very complicated.

Is the piano unique in its versatility and maintaining its ubiquity in western music? It’s been integral for hundreds of years and in the last century has adapted to modern genres, whether in its standard form or through keyboard?

I also hadn’t realised that piano literally means soft. I guess it shortened for ease of reference rather than pianoforte but I like the incongruity of Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis hammering away on an instrument whose name is the very opposite of the noise they made.

It’s hard to say. The guitar has given the piano a run for its money, especially since getting electrified, but I’d have to say that the piano is used in more genres. Totally a guess on my part, so take it for what its worth. (i.e. Not much!)

I know that we’ve discussed this before, but it seems like the piano’s peak of popularity was in the first half of the 20th century. Before radios and TVs, people would have pianos in their homes and schools and bars and churches. I think most families of some means would have at least one piano player in the bunch. Its popularity has been waning since. In any decent sized city on facebook marketplace one can find about one free piano per day. (Usually in serious need of repair/tuning).

I’ve thought about snagging one but I don’t even play my electronic keyboard much. Having a piano may make me play more but we’d probably just leave it if and when we sell the house.

Maybe whatever house we buy next will come with a piano.