When he was two or three years old, he fell three stories, hitting his head on the stone floor at the bottom.

Soon after, he drank what he thought was a bowl of milk but was actually diluted acid.

- He swallowed a pin and somehow passed it without injury.

- At ten, he fell into a river, was found floating face down and rescued, but was in a coma for days.

- He nearly asphyxiated while sleeping in a room with freshly varnished furniture.

- He was burned in an accidental explosion in his parents’ workshop and burned again when he fell into a hot stove. The burns left him permanently scarred on one side of his body.

All that happened before he reached adulthood. His mother was sure he would die young. He was nicknamed “the ghost child.”

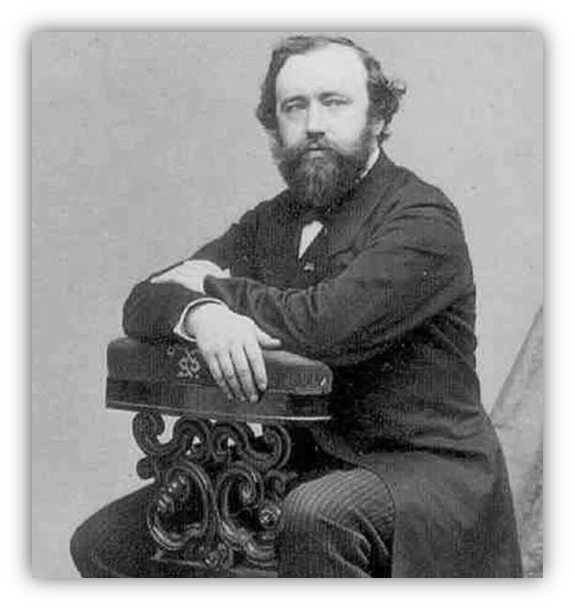

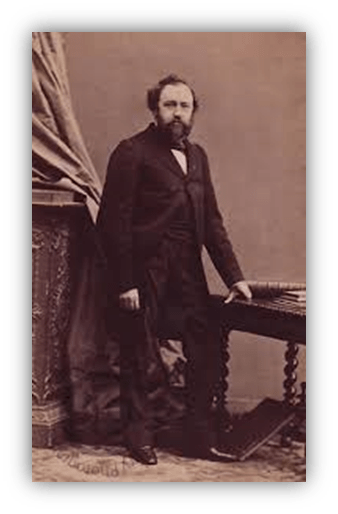

His birth name was Antoine-Joseph Sax.

No one seems to know how he came to be called Adophe, but that was his preferred name from an early age. He was born in 1814 in Dinant, which was part of the Netherlands at the time. After the Belgian Revolution of 1830, it became part of Belgium.

Both his parents, Charles-Joseph and Marie-Joseph, were instrument builders and made significant improvements to existing horns. They were among the first to add valves to brass instruments, including the French horn. This helped pave the way for the fully valved French horn, which became the standard by the mid-19th century.

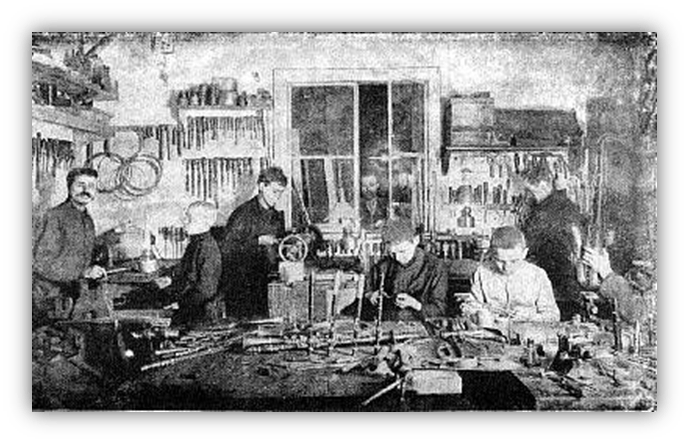

His parents taught him instrument building as a trade, so Adolphe could support himself later.

His father even taught him how to smelt his own brass, which is amazing, given the boy’s proclivity for accidents.

Wind instruments are a pipe curved into a portable size.

The longer the pipe, the lower the pitch.

If you were to straighten out a tuba and a trumpet, the tuba’s pipe is much longer. That’s why it plays lower notes. The valves redirect the player’s air through even longer tubes, which produces lower pitches.

But that’s pitch. Many other characteristics affect an instrument’s tone.

If the pipe is the same diameter for all its length, which is known as a “cylindrical” shape, it will sound bright. If the pipe gradually widens throughout its length, known as “conical,” it will sound warm and mellow.

Likewise, the shape of the bell affects the tone.

A wide, flared bell produces a broader, more resonant tone, while a small, tight bell sounds sharper and more focused. Plus, the kind of brass alloy, the type of valves, the shape of the mouthpiece, and more, all affect the way an instrument sounds.

Sax understood all of this. He made his instruments so well that when he entered a clarinet and two flutes in a competition at the Belgian National Exhibition, he was recommended for the gold medal. However, since he was only 15 at the time, the judges ruled that because he was so young, winning such a prestigious award would give him nothing to aim for the following year. This apparently happened for several years running.

It was always this way with Sax.

He was brilliant, and people either loved or hated him for it. Each success was also a failure, and each made him more eccentric, egotistical, difficult, and divisive.

He studied music at the Royal Conservatory of Brussels, concentrating in woodwinds and voice.

After graduation, he began experimenting with instrument design. The first instrument he tackled was the bass clarinet.

Earlier variations had a limited range of notes and didn’t project well. Sax used his knowledge of acoustics to place and size the holes to produce more accurate notes, and added two register keys to expand the instrument’s range. He patented the design at the age of 24.

In 1839, Sax took his bass clarinet to Paris and showed it to Isacc Dacosta, a clarinetist at the Paris Academy of Music. Dacosta had been working on his own design but liked Sax’s better. He introduced Sax to important musicians in the city. Sax would work with many of them in the coming years.

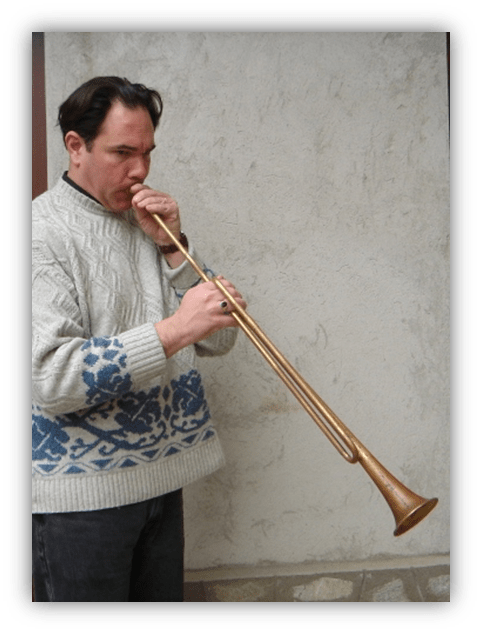

After returning to Belgium, Sax developed the saxotromba for military and brass bands. It sounded similar to a trombone but had valves and its tone was brighter and more piercing. It had limited success.

He then created the saxhorn family of instruments.

Saxhorns are similar to brass instruments that already existed — like Louis Alexandre Frichot’s English bass horn — but have conical pipes like bugles, and three valves like trumpets.

The larger, conical, caliber gives them a warmer sound than other existing brass instruments, and the valves give them the ability to play chromatic notes, unlike the bugle.

The saxhorn family ranged from the contrabass to the sopranino, but we rarely call them saxhorns today. We just call them by their pitch, like the alto horn or the baritone horn. The one you’re probably most familiar with is the flugelhorn, which looks like a beefy trumpet, and you may know it from Chuck Mangione’s 1978 hit, “Feels So Good.”

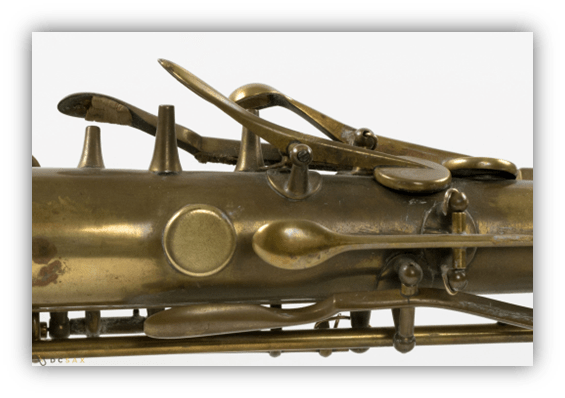

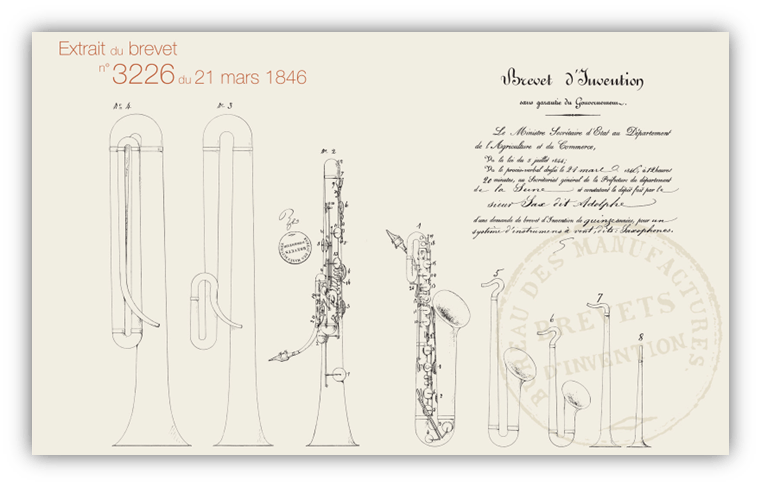

And then he invented the saxophone.

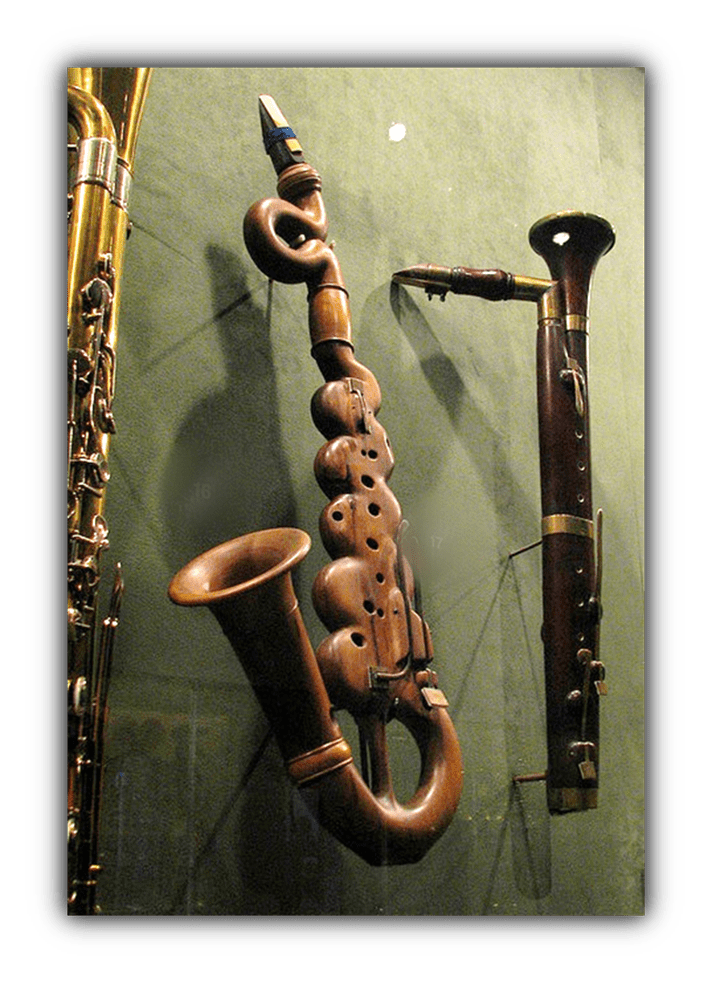

His initial prototype was a single reed mouthpiece, like the ones used on clarinets, mounted on an ophicleide, which we covered in the previous article. The resulting horn was loud like a trumpet but sonorous like a clarinet. He refined this into, more or less, what we know today as the saxophone.

It was revolutionary. Though he meant for it to be an orchestral instrument, it became more popular in marching bands and, later, big bands, Jazz and Rock & Roll.

After all, no saxophone?

Like he had done with the saxhorn, he designed a family of saxophones, from the subcontrabass up to the sopranino, though he didn’t actually build all of them. The most popular ones today are the tenor and alto, but the baritone and soprano also make star turns occasionally.

At 27, Sax again entered several instruments in the National Exposition, including the saxophone.

Word had gotten around about this new instrument, however, and at least one of the other competitors was worried about how good it was. He allegedly kicked it across the room, damaging it enough that it couldn’t be entered in the competition.

Despite that, Sax’s other instruments earned him another recommendation for the gold medal but the Central Jury gave him second place, again, and he swore off ever entering the competition again.

This loss helped him realize his future was limited in Belgium. In 1842 he moved to Paris, where he already knew musicians from his previous visit. One of the first things he did there was invite composer Hector Berlioz to come see his new instruments. Berlioz was so impressed that he wrote a glowing article for Journal des debats in which he called Sax a man of “a man of penetrating mind; lucid, tenacious, with a perseverance against all trials, and great skill.”

This enthusiastic introduction to Sax and his instruments brought him business, but it also hurt him. The same jealousies that his competitors displayed in Belgium began in competing builders in Paris.

Things boiled over the following year when composer Dom Sebastien was working on his opera Gaetano Donizetti and word got around that he planned on using Sax’s bass clarinet.

Other builders convinced Sebastien’s musicians to threaten to quit if he used Sax’s instrument. Sebastien removed it from his score.

Berlioz talked about the incident in a letter, saying, “Such is the hatred inventors inspire in rivals who are incapable of inventing anything themselves.”

Sax would sometimes challenge these rivals to duels.

Not with pistols, but with instruments in front of an audience. The winner was determined by applause and Sax invariably won, and not only because his instruments sounded better. He was a great player.

Sax introduced the saxophone to France at the 1844 Paris Industrial Exhibition by playing it behind a curtain. He hadn’t yet patented it and thought other builders would steal his design.

And he gained more ire when he approached the French military about supplying them with instruments.

The military bands were in rough shape following the Revolution, and the government was anxious to bring them up to par. Putting out a call for ideas, it came down to another musical duel between the two finalists. 20,000 people attended the concert on April 22, 1845.

Both bands would perform the same pieces written by Adolphe Adam. One played traditional instruments. The other played Sax’s instruments. The new instruments won in a clean sweep – and Sax was awarded the contract.

His win incensed his critics, saying the contract should go to a Frenchman, not this upstart from Belgium.

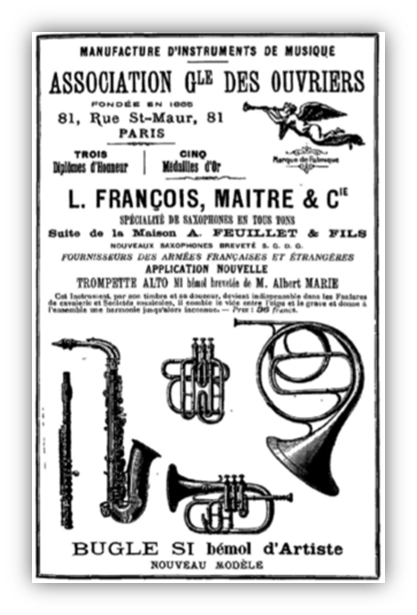

Several got together to form L’Association générale des ouvriers en instruments de musique — The General Association of Musical Instrument Workers. That’s a very nice name for a group whose only real goal was to make Sax’s life miserable.

They challenged Sax’s patent of the saxophone in lawsuit after lawsuit:

- First saying the instrument wasn’t what was in the patent

- Then saying it wasn’t musical enough to be called a musical instrument

- Then saying it was too similar to earlier instruments to be patentable.

They even purchased saxophones from Sax and sent them to other builders outside the country who replaced the Sax emblem with their own. That was so L’Association could say that Sax stole the idea from a foreign builder. It didn’t stand up in court either.

Maybe the idea was not to win these cases, but to bankrupt Sax with legal fees. It’s a standard ploy rich people do to the not-so-rich.

Sax turned the tables.

He withdrew his patent application and gave his rivals a year to show they had the skill to build saxophones.

No one did so with even a modicum of quality, so he resubmitted his application and the patent was granted in June of 1846.

Shortly thereafter, Sax’s factory caught fire. No one knows how. Then someone shot a gun at his assistant outside the shop at night. It’s suspected that L’Association were behind both incidents, and that the unknown gunman thought he was shooting at Sax.

In the Revolution of 1848, King Louis-Philippe exiled himself to England and many of Sax’s friends in high places were ousted. He lost the military contract and some of his patents were revoked. Sax appealed that ruling and won. But it took five years.

During that time, he struggled to keep his company afloat. A friend gave him ₣30,000. However the friend died and his family insisted the money was a loan, not a gift. They gave him 24 hours to repay the money in full. He couldn’t, and, like Louis-Philippe before him, fled to England. He couldn’t escape the lawsuit though, and the court ordered him to repay the ₣30,000.

To do that, he had to declare bankruptcy and close down his factory. The gift from a friend accomplished what his enemies couldn’t.

However, two years later, the new French leader, Emperor Napoleon III, made Sax the Musical Instrument Maker to the Household Troops. He returned to France, reopened his factory and paid off all his debts.

During his time in England, he noticed a small black growth on his lip. By 1859, the cancer was so big that he had to eat through a tube. The traditional medical treatment of the time would have removed at least part of his jaw. He turned to a doctor from India who treated him with a mixture of herbs. In less than a year, the tumor disappeared entirely. It may have been the herbs or it may have been Sax’s willpower.

This, after all, is the man who said, “In life there are conquerors and the conquered; I most prefer to be among the first.”

He continued making instruments for the rest of his life, and came up with some other inventions. Two ideas that were never built were an organ on a hill that would have been so loud that it could be heard all over Paris, and a cannon big enough to launch a 500 ton missile that could destroy an entire city. He called it, of course, the saxocannon.

Sax declared bankruptcy twice more, in 1873 and 1877, primarily due to continued attacks by his enemies. The irony is that, as the patents expired, rival instrument builders made money copying his designs. He wrote an essay appealing to the public for support, saying that the French musical industry was worthless until he arrived:

“I created this industry; I carried it to an unrivaled height; I developed the legions of workers and musicians, and it is above all my counterfeiters who have profited from my work.”

His egotism didn’t change any minds, but his friends asked the French government to provide Sax with a small pension for his remaining years. It was granted and he lived until pneumonia took him at the age of 79.

His youngest son, Adolphe-Edouard Sax, took over the business in 1894. Adolphe-Edouard ran the company for many years but it had continued financial problems.

He sold it to the Selmer company in 1929. Selmer is one of the biggest musical instrument makers in the world today.

In 2012, Karel Goetghebeur, a Belgian saxophone player and former funeral director, bought the rights to the Sax name.

His idea was to return the saxophone to its home country and he opened the Adolphe Sax & Cie. factory in Brugge. Goetghebeur also runs a company called Sax4Pax that makes saxophones out of artillery shells left over from the world wars.

And if you ever visit Dinant, there are tributes to their hometown hero everywhere.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Riveting story on this man. I actually knew he invented the saxophone, unlike most of the inventors covered in this series.

(I did get the metronome half right ) I just didn’t know anything else about him and it was quite the bumpy and fascinating ride.

A talented saxophonist at my church got married this past May and in addition to playing the piano, I was asked to play alto sax on a couple of songs. Interesting fact about this is that I don’t play the saxophone. She told me that since I played clarinet and the fingering was basically the same, she had faith that I could pull it off. I told her I would try. It was way harder than advertised. The best I could manage was to play the beginning part of the Mendelssohn Wedding March in harmony with another sax player. It was two notes. I considered it a monumental achievement to get through it fairly in tune and without squawking. The bride was very pleased. In the end, that’s all that matters.

I can relate. I played the Wedding March on a small Casio keyboard at my sister’s wedding. Interesting fact about this is I don’t play keyboards. It went OK until the end when I hit a Fsus instead of an F major, but in the moment I thought, “Hey, that’s the Amen cadence!” and just went with it. I might be the only one who noticed.

Sax’s life was a roller coaster of wins and loses. Makes you wonder how much of that we bring upon ourselves.

Oh for sure that Fsus was salvageable and it sounds like you made it seem as if it was on purpose. Nice recovery. Co-inky-dink here. One of my sisters got married in a courthouse and I played the Bridal March (Wagner) on a tiny Casio!

Mine was the SK1, their first sampling keyboard.

Ah, I remember that one well. Mine was the MT-30.

My favorite is the MT-58.

❤️

And mt, did it have to be Kenny G referenced in the teaser? I would have preferred any of the following-

John Coltrane

Charlie Parker

David Sanborn

Cannonball Adderley

Clarence Clemons

Lester Young

Sonny Rollins

Branford Marsalis

Junior Walker

Boots Randolph

Dave Koz

and ANYONE ELSE

and yes, that includes Sting

Not forgetting Lisa Simpson.

Of course! And Bleeding Gums Murphy. How could I have forgotten either of them?

I loved Square Pegs. I just checked to find out the name of The Waitresses’ sax player: Mars Williams.

What a life, what a story!

Could be the stuff of a riveting biopic.

After all the adversity he deserves his place in history.

Great idea! I hope a filmmaker sees this.

I played (or attempted to play) tenor sax in my junior high band. Let’s just say that I found out that that wasn’t going to be my life’s calling. As much as I enjoyed it, I wasn’t too great!

SrCarto, back in the house! Very nice to see you here!