Edwin S. Votey was born in the Finger Lakes region of New York in 1856.

He went to public schools, became interested in mechanics, and developed strong engineering skills.

When he was 17, his father was hired as pastor at the Baptist church in West Brattleboro, Vermont.

The church still stands. Soon after moving there with the family, young Votey was hired as a clerk by the Estey Organ Company in Brattleboro.

It was a leading manufacturer of musical instruments, and Votey quickly rose through the ranks.

He became an expert in organ design and mechanics, and traveled as a reed organ salesman and technician. During this time, Votey married Annie Gray, who was also from the Finger Lakes. They had three children together. Word about his talents must have gotten around, because he was offered a position as Technical Director at the Whitney Organ Company, and the Voteys moved to Detroit.

C.J. Whitney had purchased the failing Detroit Organ Company, renamed it and hired new people, including W.R. Farrand, the son of a profitable drugstore owner, as Administrator. It was a success.

Whitney retired in 1887 and sold the company to Farrand and Votey.

They renamed it the Farrand & Votey Organ Company.

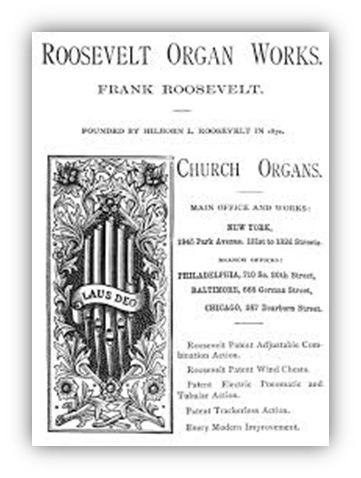

Votey then spent half of 1890 in Europe selling their instruments and studying pipe organs. When he returned, Farrand & Votey used what he learned in deciding to buy the Roosevelt Organ Works in New York City, a manufacturer of pipe organs. They made some of the biggest church organs in the country, mostly in the eastern United States but also as far away as La Compañía de Jesús Church in Quito, Ecuador.

The company had been started by brothers Hilborn and Frank Roosevelt, who were cousins of Theodore Roosevelt. Following Hilborn’s death, Frank put the company up for sale.

The sale included several patents related to pipe organs, like methods of controlling air flow and making the keys more responsive to the player’s touch. These patents kept additional money coming into the company after Farrand and Votey bought it.

Votey held over twenty patents of his own, most having to do with organ design. He later patented a pilotless airplane that would drop bombs behind enemy lines in World War I. The war ended before any could be made.

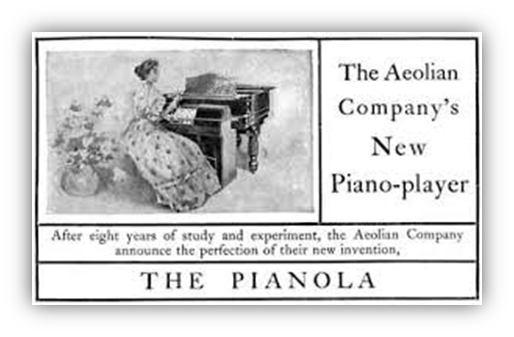

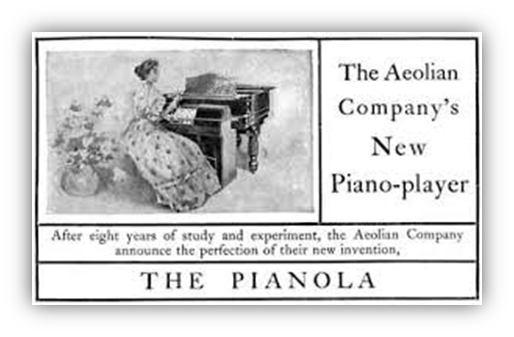

In 1898, Votey became vice president of the Aeolian Company.

That’s when he used his engineering and industry acumen to invent the Pianola, an automated piano player.

By the mid-1800s, there were lots of self-playing instruments. From tiny music boxes to the componium and the panharmonicon to the huge calliope, the concept of musical automatons was nothing new. No one, however, had made an affordable self-playing piano. There were attempts at devices that attached to existing pianos. They had mechanical pistons that pressed the keys but, even when they worked well, attaching and removing them was a chore.

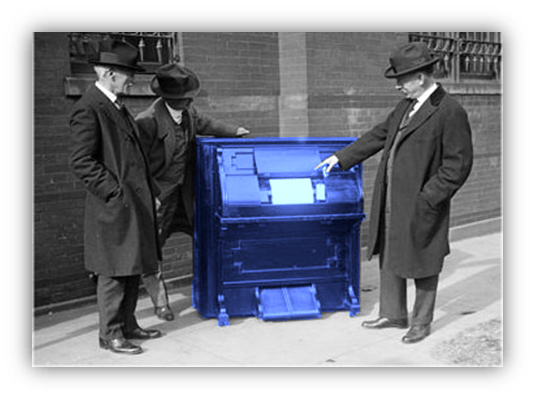

Votey’s Pianola was a step forward. It was sometimes called the “push up” player because it was on wheels and users would push it up to their piano’s keyboard.

After aligning it just so, the users would then sit behind it and pump the pedals with their feet. Wood fingers pushed the piano’s keys.

The Pianola had several shortcomings. The piano couldn’t be played manually when the Pianola was in position. It had to be wheeled out of the way. It was huge, so storing it was a problem. And it was expensive, but the people who could afford it loved it.

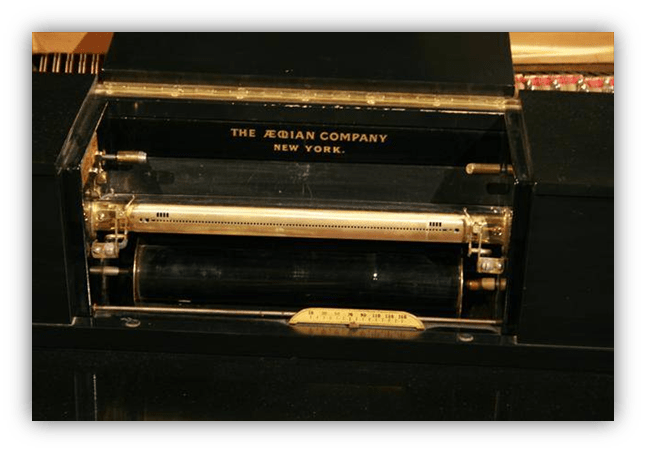

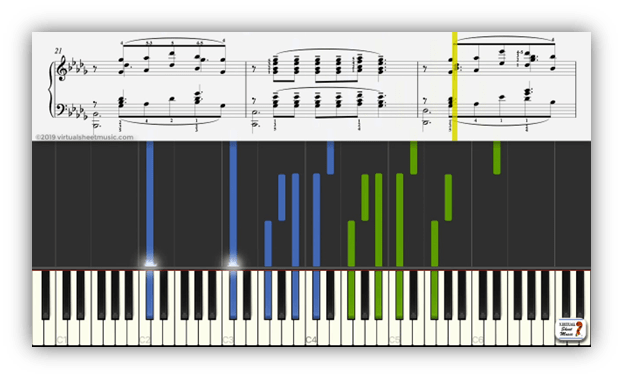

The mechanism itself is clever. The foot pedals pump bellows to create a vacuum. Reservoirs keep the vacuum consistent even when the person pedaling isn’t.

The vacuum sucks air in through a row of small holes in a rounded brass plate called a tracker bar. Each hole corresponds to a note on the keyboard.

The vacuum also powers a small motor that pulls a paper roll from one spindle to another across the tracker bar, and the paper has holes in it.

As a hole in the paper passes over a hole in the tracker bar, the released vacuum has enough power to play a note on the piano. Small holes make short notes. Long holes play long notes.

Each paper roll contained one song. Some rolls even had the song’s lyrics so you could sing along as the roll passed over the bar.

The paper roll was patented in the United States by Emil Welte of Welte & Sons. He was one of the sons. It was a German company who made orchestrions — automatic music machines — that used paper rolls so owners could switch songs. Paper rolls were also used experimentally in various organs.

John McTammany, a Scottish immigrant to the United States, had the concept to use paper rolls on pianos. The idea came to him while he was repairing a music box.

He worked on various devices hoping he could create a player so easy to operate that “a country clodhopper could play a Beethoven Sonata.”

He took his prototypes to Boston and New York hoping to sell the design to instrument builders, but the companies, either shortly before or after his visits depending on who you believe, had their own players.

McTammany may well have invented the use of paper rolls in player pianos, and held the patent on it, but he spent a lot of time and money suing companies who used it or any somewhat similar design. That was time and money he couldn’t use to manufacture his own pianos. He gave up on the music business and worked on his other major invention which used the same pneumatic components from his piano roll system in one of the first vote counting machines.

The paper roll mechanism, the bellows system, and all the distinct parts were created by various inventors and craftsmen over many years, including Welte and McTammany. By the 1870s, automated piano players existed and more or less worked.

But Votey put all the pieces together in the elegant and functional Aeolian Pianola.

It was the first consumer player to gain any popularity, despite its drawbacks.

Votey showed that a commercially viable self-playing piano was possible, and that’s why he’s considered the inventor of the player piano.

The Pianola quickly drew the attention of other piano manufacturers, who went to work on their own variations.

In 1901, only three years after the Pianola’s introduction, the Melville Clark Piano Company made the first all-in-one player piano, with the player mechanism built into a standard piano.

By 1924, half of all pianos sold were player pianos.

At a 1908 industry conference in Buffalo, New York that became known as the Buffalo Convention, several prominent piano roll manufacturers agreed on a universal format for 88-note player pianos. The standard roll would be 11.25 inches wide with nine holes per inch. From that point on, any roll could be played on any piano.

Famous pianists recorded works for piano rolls.

We know how Claude Debussy wanted his composition “Clair de Lune” to sound because he recorded a piano roll of it.

Likewise, Sergei Rachmaninoff, George Gershwin, Scott Joplin, and Jelly Roll Morton all recorded for the player piano. Many of these can now be heard on YouTube.

While it was a long time before the formalization of the Billboard, Cashbox, and other systems, the popularity of songs was tracked by sheet music sales.

Through the 1910s and 20s, some charts included sales of piano rolls, too.

These days, piano rolls are a thing of the past.

Contemporary player pianos use MIDI files to play songs.

These files can be digitally edited. Paper piano rolls can only be edited with cellophane tape and a razor blade.

In the first quarter of the 20th century, it was common for families to have pianos in the home. In the evenings, people would play and sing together. With the advent of radio, and later television, piano sales started to fall. Votey lived long enough to see that, but when he passed in 1931 he knew the effect he had on the music industry.

Beyond his pipe organs still in use in churches and cathedrals, player pianos made millions of people happy, or consoled them in hard times like the Great Depression, or encouraged them to take piano lessons.

His first Pianola is in the Smithsonian.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Player pianos have always had a certain appeal to me, and it was interesting to see how they came about. I do have one related story. When I was in junior high, a bunch of us put on a haunted house in a friend’s basement. They had a player piano and we decided it would set the right vibe to have a piano playing by itself as people came in. We needed it to be playing something that would sound spooky, so we took a look at all the rolls, but nothing looked familiar. I saw Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in C# Minor, and I suggested we try it, though I had never heard it before. It was in a minor key and I knew Rachmaninoff was a stone-faced, scary looking guy that never smiled, so I thought it might work. The first three notes were bone chilling and we knew immediately it was perfect. After reading your article, I am now wondering if it was one of the rolls Rachmaninoff recorded himself. That would be cool.

My player piano story is my family visited friends who had a cabin in northern Maine. The had a player piano and several dozen rolls but my sister and I, we must have been about 11 and 12, played “Alley Cat” over and over. That poor family.

https://youtu.be/p4ftK2J0uIU

In 4th-5th grade I took organ lessons. I guess my mom envisioned me becoming a church organist someday? Of course, like the average kid forced to take lessons, I had a pretty bad attitude. But the one song I did learn before convincing my mom to allow me to quit, was “Alley Cat”. Foot pedals and all. Sure, I wish I had stuck with it, but whattayagonnado?

I played Alley Cat on the piano all the time as a kid. The organist at the roller rink played it a lot as well. Oof, I forgot how old I am.

I thought “Alley Cat” was much older but I just looked it up on Wikipedia and it’s from 1962. It got to #7 on Billboard and won a Grammy for Best Rock & Roll Recording. In what world is “Alley Cat” Rock & Roll?

Oh yeah. This one.

That’s an interesting statistic there…50% of pianos sold in 1924 were players. I’ve learned that a fair number of pianos out there today (our family’s piano included) used to be player pianos, but later had the mechanical stuff removed. I’m not sure why. Maybe the player functionality broke, so they removed them?

I’ve hunted on ebay and facebook before…there are plenty of player piano rolls that still float around out there if one wanted to start up a collection.

It’s tempting….

Shedding new light on a staple of comedy shows and cartoons. I can’t remember a specific show that I’ve seen player pianos featured in but they’re familiar enough that I’m sure they cropped up numerous times in my childhood viewing.

Potentially stupid question but could you play the player pianos normally or was it only possible to use them in automated mode?

And were there outcries from pianists and organists the world over that these new fangled contraptions were stealing their jobs?

Not only could you play player pianos normally, you could play along with them while they were playing a roll. Wanna solo over “Moonlight Sonata?” Now’s your chance.

I haven’t heard of any musicians objecting, maybe because the player pianos were meant for the home. They did show up in bars and restaurants once they became electrified. Before that, someone had to sit there and pump the pedals, so you might as well hire a musician.

Meanwhile on the Piano Rolls Chart… (The Number Ones Comment Section If It Existed In The Virtual 1920s)

The player piano is featured in HBO’s Westworld. The gimmick of hearing rock songs being de-rocked never gets old for me. My favorite is the player piano version of “Paint it Black”. In the early-20th century, was teenagers irritating their parents a thing? What sort of sheet music do you think would cause a strict father to say kids these days?

“Alley Cat,” if a couple of preteens played it over and over again.