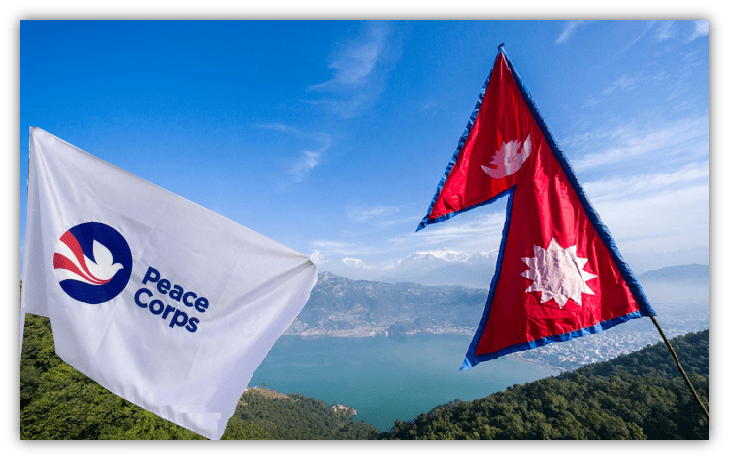

In today’s post I will focus on the reality of working in the Peace Corps.

It is amazing in its own way, as long as you let go of any expectations you may have had coming in.

The Peace Corps mission is ridiculously simple:

To promote world peace and friendship by fulfilling three goals:

In my mind, based on a commercial I saw when I was young, I always thought that Peace Corps volunteers were digging ditches in the desert or other sorts of hands-on, tangible kinds of tasks.

Well, guess what? Nepal (and every other developing nation) has an oversupply of unskilled manual labor – they don’t need some outsider doing a job for free that local people can do for a wage and (barely) feed their families.

What they need is expertise; training.

- They need to learn how to build their roads to higher safety standards.

- They need to learn to make water systems less likely to cause cholera outbreaks.

- They need to learn modern medical practice to achieve better health outcomes for their patients.

- They need to learn modern practices to conserve their natural resources, such as soil and forests.

That’s where we come in.

In order to join the Peace Corps, most people need to have a college degree – with a few exceptions, such as master tradesmen (electricians, carpenters, plumbers, etc). So we had people with degrees in engineering, nursing, forestry, and education, among others.

My group had a large number of nursing and natural resources volunteers.

Here’s the rub: some volunteers have very defined roles and workplaces, and some not so much. If you’re a nurse, you’ll work in a nursing school and teach nursing courses 6 days a week. Same if you’re a teacher – you have a classroom and students, and it’s pretty clear what comes next. However, if you’re an engineer (or a forester, or a water and sanitation volunteer, etc), you get assigned to a government office… and then what?

Some people spend their whole two years in the Peace Corps wondering, “Now what?” You don’t get a budget (unless you have a family or community who can donate funds on their own), so you really can’t take the lead on any of your own projects. You are at the mercy and the limitations of your office and co-workers.

In my offices’ cases, corruption was so rampant, that my co-workers were actively preventing me from getting involved in any of their projects – I think they didn’t want any foreigner eyes scrutinizing these interactions.

(Sidebar: when I was in Nepal, there was an understanding of “acceptable corruption” versus “unacceptable corruption.” As I mentioned in my previous post, the regular salaries of well-educated Nepali government workers could barely feed a family.

A few side deals with contractors could help keep the family afloat, and this was widely practiced and acceptable, though unspoken. However, people who were egregious in their corruption were shamed and sometimes exposed.

The engineer in my first duty station office was ran out of town quite expeditiously due to his excessive corruption – and an affair with a married woman.)

So in my first duty station office, I tried to find ways to be useful.

They had a single computer there, in a room off to the side and never used. So I taught many of the technical staff how to use a computer. The very basics – how to turn it on, how to double-click a mouse, how to type. As long as I was there, it was never used for any official purposes, but I figured giving these guys exposure to a computer would come in handy at some point.

My second duty station was in a larger city, with actual computers that got used. So I taught several of the technicians there how to use basic AutoCAD (Computer Aided Drafting, the way construction drawings have been produced for a few decades now).

But I really never got to get involved in actual engineering projects with my offices. Partially, they didn’t want me involved in their business, but also, I really don’t think I had much to offer.

This relates to another sort of Peace Corps issue.

When you look at the people who join the Peace Corps, you have a very large population of 20-somethings and a smaller but still decent population of 50-somethings and 60-somethings. Virtually nobody in their 30’s and 40’s. At least this was my experience in Nepal; not sure if it’s specific to this country or to that time frame, but I doubt it.

Think about it – you’ve got a lot of recent college graduates and empty-nesters. Most people in those in-between ages are either in family mode or career mode. Neither mode is conducive to moving away from your world for 2+ years to volunteer in the developing world.

So I was a recent college graduate, with virtually zero practical engineering experience, going into a foreign country with very different means of design and construction. Honestly, I was fairly useless. They did designs using rules of thumb and written guidelines, and they seemed to work fine. Not only did nobody have access to a computer, but even scientific calculators were exceptionally rare (no old fogies, they didn’t have slide rules either, and I would not have been able to show them how to use it if they had).

So I found ways outside of my official office workplace to try to make a difference. I worked with another volunteer to design and build a new school building in Palpa District – close to where I had my training (he crowdfunded it through his friends and family). I gave a presentation to community leaders in Biratnagar on the consequences of environmental pollution and how they could work proactively to prevent future problems – this soon led to a ban on plastic bags. I worked with one village an hour bus ride down the road and taught them how to chlorinate their water supply. (BTW, all of these were team efforts – I don’t get sole credit for any of it.)

But let’s face it, I was not as successful in the first mission as I was in the 2nd and 3rd missions.

(I guess these articles are meeting the 3rd mission as we speak.) A lot of my daily life was having tea with friends, coworkers and acquaintances, just sharing my own experiences and listening to theirs. Having conversation, sharing a laugh, just hanging out – I could justify that doing these things was meeting my mission. I wasn’t being lazy; I was following the Peace Corps mandate.

I got a LOT of recurring questions, the most common of which was definitely, “Are you going to marry a Nepali woman?” I think I answered this many different ways over the years I was there, but one time I was not in the mood for it, so I asked the guy in response, “Why, do you have a little sister you can introduce me to? A big sister? An aunt? No?

“Fine, then introduce me to your mother.”

(I may be lucky to be alive after that exchange.)

I also got a lot of questions about what kind of meat we eat in America (it was always “America,” never “United States”). So I would say we eat chicken (so do they), we eat pig (rare in Nepal but available), we eat cow (sacred and quite illegal in Nepal, but they are aware that it’s eaten in other parts of the world), we rarely eat goat (very common there), and we don’t have water buffalo (fairly common there). Then I would usually tack on, “And we eat people too.”

Upon saying this, I’d get laughing and people calling BS, but I’d always elaborate a story about how we don’t commonly eat human meat, but only when a loved one dies, we eat a small part of the hand as a way to keep them as part of us after they have departed. I’d say I’ve eaten human meat twice, when my grandfather died and when my uncle died. Still 75% knew I was BS’ing, but I did get a few people give me a disgusted look. Maybe they believed me? (For the record, I was BS’ing, and I have never – knowingly – consumed human meat.)

Anyway, I knew other volunteers who made no pretense about making any effort towards the first mission. They spent the entire two years just hanging out, figuring 2 out of 3 missions is a 67%, which is a passing grade. They showed up at the office purely to socialize. And the Peace Corps organization does not really evaluate you – you’re not going to get in trouble for not being productive. They mainly just want to bring you home in once piece.

Even if the job was often not technically challenging, it could be psychologically or morally challenging.

About halfway through my service, I went through a pretty severe depression cycle about the unfairness of why I got such an easy life and these people had such hard lives based on nothing more than the random luck of where we were born. I don’t think I was alone in this sort of mentality. Luckily, we had excellent medical care available – even for our mental health issues. I think the Peace Corps organization was so focused on our health and safety, anything we actually accomplished was gravy.

When I was in Nepal, many volunteers didn’t make it for the full two year commitment. It was typically 60-70% of the volunteers who made it. Among the 30-40% who didn’t make it, some had medical issues that forced them to leave; others just couldn’t handle the culture shock; others still just got tired of it and wanted to go back to their old lives. We had one woman in our group who arrived to Nepal, then turned around and got back on a plane to the United States the very next day. I knew a guy who quit 3 months before his full term of service was complete – he wanted to start school and get back with his girlfriend.

Those of us who made it, it’s definitely like a badge of honor, but those who didn’t are still cool – we could have been in their shoes easily with a little turn of fate.

Looking back now, I can see I could be about 1,000x more useful in teaching engineering at this point in my career than I was back then as a fresh faced recent graduate. Maybe when I’m an empty nester, the opportunity will present itself again, and I’ll be in the other demographic (not likely, but not impossible).

So when people say that the Peace Corps is “the toughest job you’ll ever love,” it absolutely is! But the definitions of “tough” and “job” and “love” and even “you” will be altered from whatever you may have previously imagined.

Let the author know you liked their article with a “heart” upvote!

Wow, thanks for this report! It’s a real keeper for me, as I sometimes have students who talk about the Peace Corps as an option. Showing them this, I hope, will help them continue to keep it as an option but be more realistic and less starry-eyed in approaching it.

Ya know, you have to be a little starry-eyed to pursue something like Peace Corps. It’s a huge leap of faith, particularly for Americans who tend to live a very insular life. There are some incentives that come with it too… partial forgiveness of student loans, an advantage in applying for federal government jobs. I took advantage of both of those after my service concluded, but they were 0% of my motivation to join in the first place. I wanted to put my engineering skills to use in a way that would be most beneficial. Kind of didn’t work out that way exactly, but I am still very grateful for the experience.

It really seems like a challenging and deeply rewarding experience.

My experience studying abroad in Japan was challenging and eye-opening in its own way, but it simply can’t compare to the level of immersion that you experienced working in Nepal.

Even though your immersion was never complete, and you constantly felt the boundaries of a more-or-less diplomatic privilege setting you apart, even witnessing and feeling the many facets of that disconnect can really open your eyes to important aspects of life around the world.

The depression was perhaps a sign that it’s a lot for a person to process, but hopefully most people in the program come a way with a much richer perspective of human life. Not just the bits found on postcards or “World Music” bins, but the messy, chaotic, cruel, dumb, generous, humbling, and heartening moments that make up our world.

You said it better than I could have myself, Phylum. Being a foreigner of Western descent in Nepal means constantly living in the fishbowl. Outside of big cities or tourist areas, foreigners are exceptionally rare, so you get gawked at constantly. Kids always shout “Namaste” at you, or they practice the same question in English, “What is your name?” It’s cute at first, then after 10 times a day for months, it gets REAL old.

The fun part is that I found most people in Nepal are very curious, and once you can get past the fishbowl effect and sit and talk to people, there are so many fun and educational conversations to be had. I tried to be as Nepali as I could, to be as immersed as I could, but there was always a remove that could not be bridged. Even if I lived in Nepal for 30 years and had perfect Nepali diction, I could not erase my physical differences or my privileged upbringing.

I don’t think anyone who joins the Peace Corps (and stays in) doesn’t come away a changed person. And that change is for the better… a very different perspective on the reality of the world outside the US, the day to day lives of other people. A keen sensitivity to your limitations but also the power of cultural exchange. I think if everyone spent a year in a very different circumstance than the one they already know — could even be here in the US, but among a different socioeconomic group and in a different geographic location — we would be SO much more empathetic and decent than we are.

Is it the Amish who have their young adults leave the community and live on the outside for a year? Some don’t come back, but those who do have a better understanding of themselves and their flock.

I never realized how sweet American food is until I went to Europe for the first time. You really don’t know the place you’re from until you go somewhere else. A year abroad should be the norm for every young person.

Yes, it’s the Amish tradition of Rumspringa.

If you haven’t seen it already, the documentary The Devil’s Playground is quite a compelling watch.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n518iLqRekM

in Australia and New Zealand, a young person’s CV is expected to have a year “missing” because they believe everyone needs to “get away” for a bit.

Therefore, some companies might be hesitant to hire a late 20s person for a career position who doesn’t have it, knowing they might leave soon.

Here in the U.S., if someone has a year of NOTHING on their resume, most have to explain why.

Interesting read, particularly seeing how the Peace Corps mission comes up against the realities of the culture and way of life in another country. Its to your credit that despite the difficulties in getting involved in projects you used some initiative and found a way of making a difference.

I still feel like I didn’t do nearly enough. Fresh out of university, I had no experience with the level of initiative you need to be successful in a program like that.

In some ways, the British VSO system works a bit better. Like they have fewer volunteers, but are more intentional with placing people with the right skills in the right places.

I think about the Peace Corps at least once a day, Pauly Steyreen. If Hungary and Poland were on the list of posts, I’d give it some serious thought. Armenia is the closest country. I compartmentalize the news. I just have room for the war.

Pauley, thank you for the very informative update as to the way the Peace Corps really works.

I’m old enough to remember when JFK presented the program to the American public and at that time we thought we had all the answers to the world’s problems.

I remember a student who was ahead of me in high school and joined the Peace Corps and came back a year later shaking their head.

“They wanted me to dig ditches but I’m a math major. I thought they wanted me to teach them how to count but they just wanted to get water to the village.”

Sometimes, I really think what we really need is someone to say “If you have this knowledge, go here and if you have that knowledge, go there”.

But so many times, we work at cross purposes and what should be simple solutions become complex ones that no one wants to work on.

“Here’s the rub: some volunteers have very defined roles and workplaces, and some not so much.”

A physical education teacher I worked with in Damascus started his career overseas with the Peace Corps. His first assignment was to “live” in western Iran and have the locals get to know he and the other Americans.

They smoked pot and hashish almost every day. The Iranian Revolution started about 5 years after he’d left. Coincidence? I think not.

I had a few fellow PCV’s who took that same approach to their service. Spend a couple of years gettin’ high with the locals. Maybe I underestimated their contributions to the world?