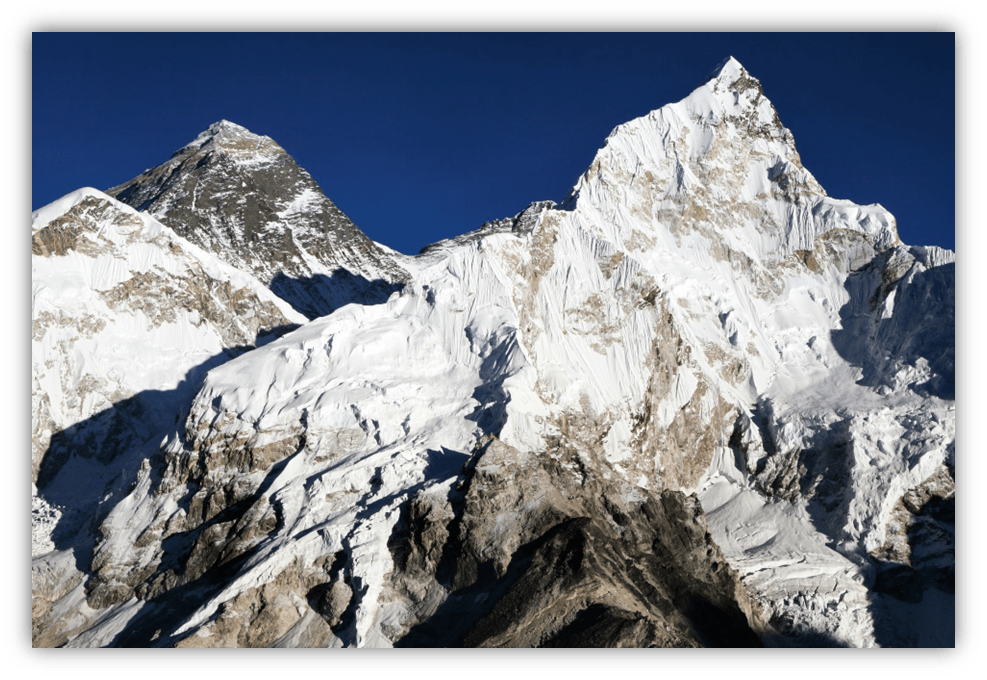

A lot of people associate Nepal with the Himalayas, and certainly, they are there!

If you go to Nepal, you will probably see them at some point – on a clear day, they are visible from most anywhere in the country (emphasis on “clear day” – not a given).

But saying Nepal = Himalayas is like saying California = beach and sun. Reductive and inaccurate.

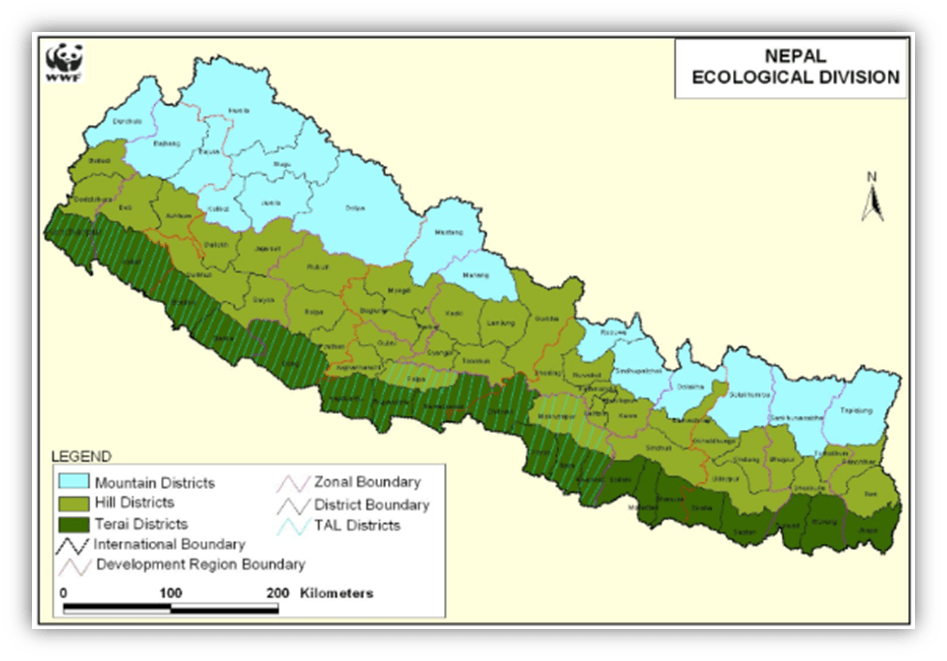

Nepal is roughly the size of Illinois with a population of 29 million. Imagine it like Illinois on its side, much wider than it is tall.

Roughly the top third of Nepal is the Himalayas, very rugged, remote and sparsely populated. Of course, this is where the tourists go (more on this in a future column). Much of this land is uninhabitable, too steep, too rocky, or too cold for life to flourish. Besides tourism and religious significance, this part of Nepal doesn’t count for much. There are a few ethnic groups with small villages here, but even these small villages are either A) on a tourist route and depend on tourism dollars, or B) are only inhabited on a seasonal basis.

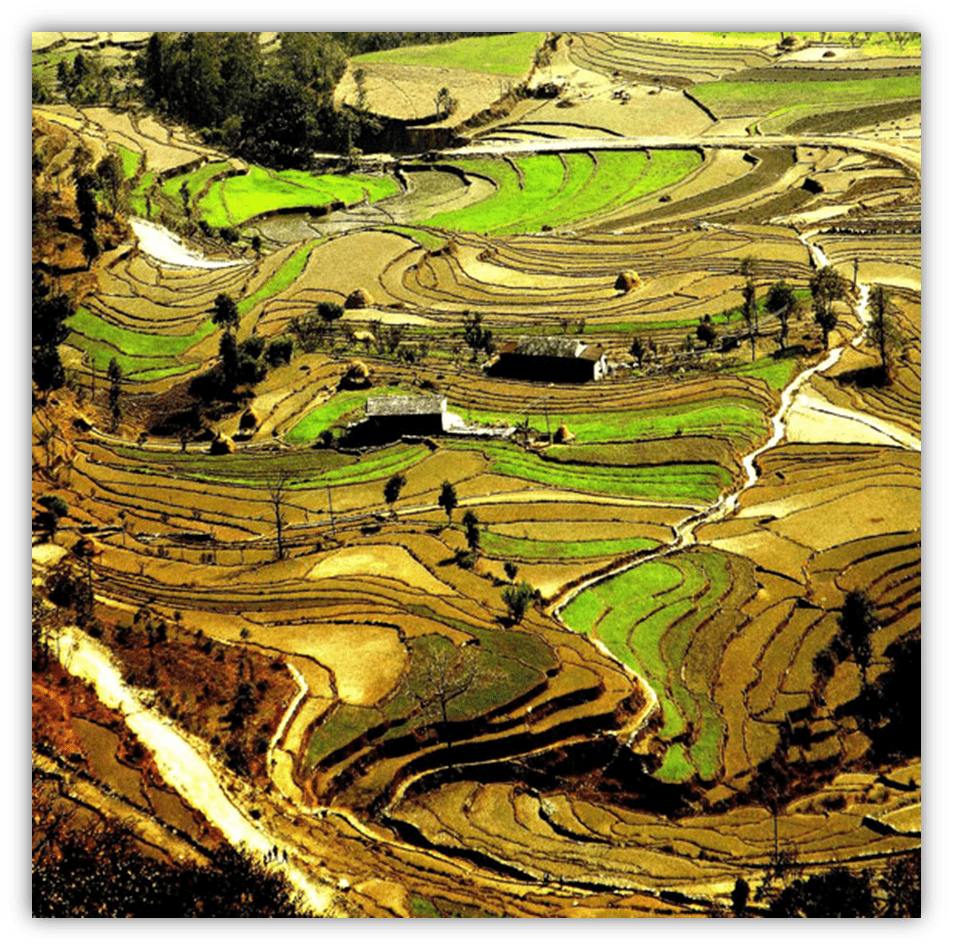

The middle third of Nepal is the smaller mountains and hills. Many of these are still tall mountains by U.S. standards, often exceeding 7,000 feet in elevation, but this area is very populated. The hills are all terraced with rice fields, so they look like real life topo maps from above.

This middle third of Nepal is considered by Nepali people as the “real Nepal”. Contrary to what you may imagine, there’s not a lot of unspoiled nature. People and villages and towns are everywhere. You will find forests, but you won’t go very long before you find houses, farms or settlements.

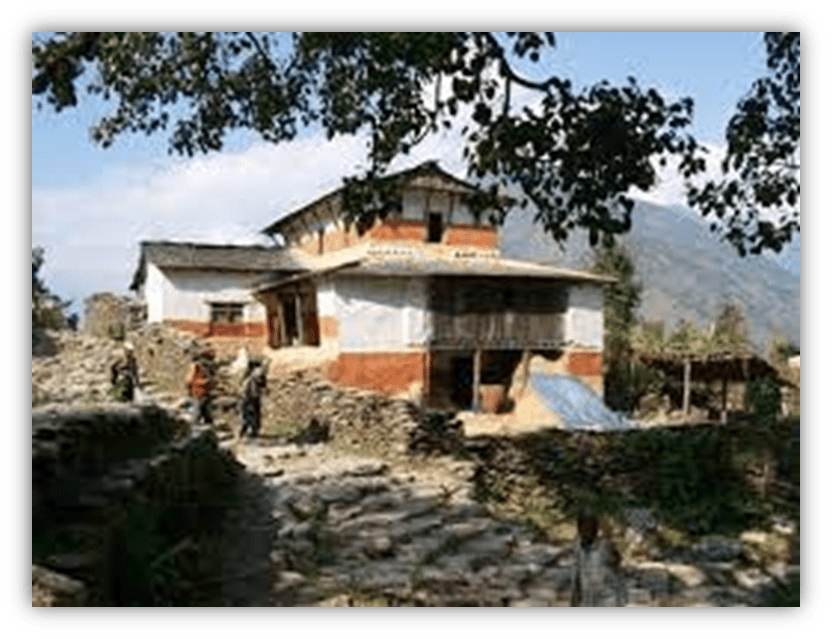

Interestingly, the older and more well-known towns are on the ridge of the hills, and towns closer to the valley floor are relatively new. The mosquitoes that cause malaria used to be rampant in the valleys, but did not survive at higher elevations. So people would walk down to the valleys to work the land, but would always return to homes at higher elevation before dusk – when malaria-causing mosquitoes are most active. However, since malaria eradication began in earnest in the 1960’s, those lower elevation locations have become inhabitable, and numerous villages and small towns have been formed.

When I was in Nepal, the vast majority of the population were subsistence farmers, raising rice primarily in fields terraced into each and every hillside. Many villages have only one tiny general store, which is the bottom floor of a family’s house. Houses are mostly made of stone masonry with mud mortar and thatch roofs. Floors and lower parts of the house are often made with gobar ko lipnu, which is a mixture of mud and cow dung.

My 2 ½-month training in Tansen as well as my first year as a Peace Corps volunteer in Taplejung were in this hill part of Nepal. The cities of Kathmandu and Pokhara are also in this part of Nepal.

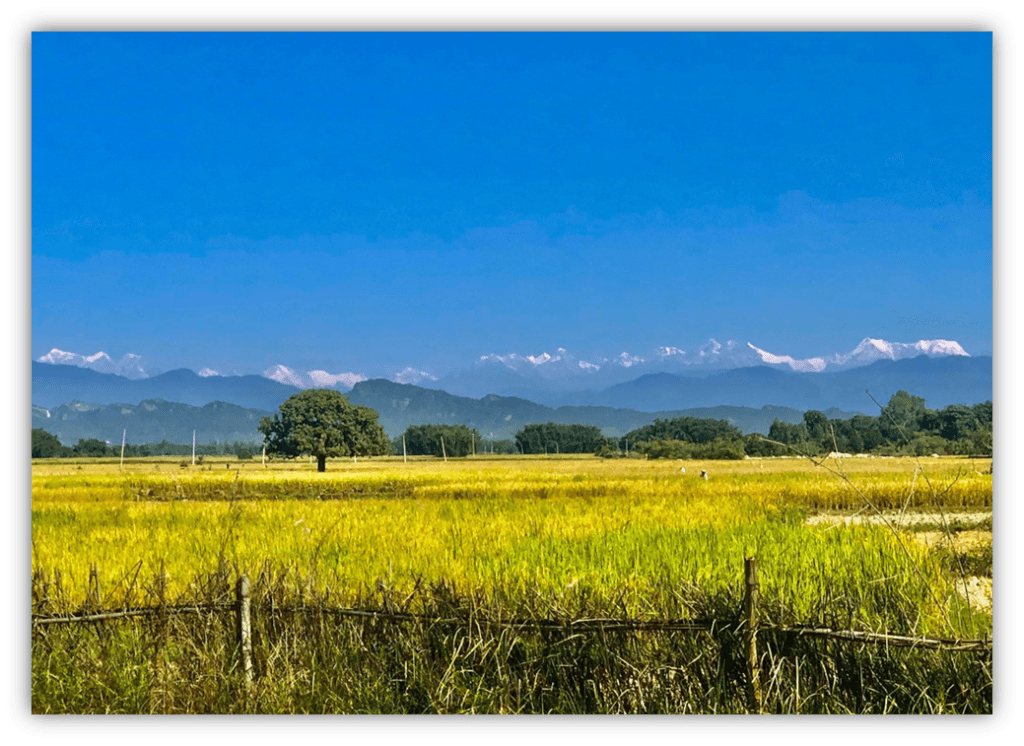

The southern third of Nepal is completely flat, flat as Kansas, or the southern neighbor, India. This area is known as the terai. It is very agricultural and quite densely populated. There are more large cities here, with fewer geographical barriers to urban sprawl. The terai is in some ways like an extension of India – it is culturally and visually similar to north India (Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and West Bengal), and the border is open for local Nepali or Indian people – only foreigners need to pass through customs.

While the hills may be the “real Nepal,” the terai is where a majority of Nepali people live. I lived in the terai in Biratnagar for my 2nd year as a volunteer. At the time, Biratnagar was the 2nd largest city in Nepal, with about 200,000 people (now it’s 6th). Along with agriculture, the terai is also home to the limited manufacturing sector that exists in Nepal.

Contrary to popular belief, Buddhism is not remotely the most common religion. Nepal is mostly a Hindu country – as you may have deduced from the presence of cow dung in their building materials. Over 80% of the country is Hindu, only 9% is Buddhist and 4% Muslim.

One of the coolest things about Nepal is its ethnic diversity. About half of the people are Hindu caste, but the other half are ethnic groups that have their own history, language and cultural identity. This was best exemplified by Taplejung, my first duty station in the far northeast of the country, which has significant populations of Limbu, Sherpa, Rai, Gurung, Newar and Hindu caste people, none over 40% of the population. In Taplejung, people largely respect the traditions of others, and inter-caste or inter-ethnic friendship and marriages are not uncommon. (Other rural parts of Nepal are not so progressive, and inter-ethnic marriages are less common.)

To give a very specific example of this respect, the Nepali word for banana is kira, but in the Limbu language (the largest ethnic group in Taplejung), that word is a profanity. So everybody in Taplejung, regardless of ethnicity, uses the Limbu word for banana – kola. You’re just as likely to hear Namaste (Nepali way to say hello) or Aishewaro (Limbu way) as a greeting, and nobody takes any offense if it doesn’t match their own expectation. In other words, there’s no bullshit War on Christmas in Nepal – respect is given in the way the giver understands it (their own cultural or ethnic perspective) and it is received with universal appreciation. If you’re blessing me in your way, I appreciate it, even if it doesn’t match the way I’d do it.

Of course, don’t take this to mean that Nepal is some sort of utopia. There’s still a lot of gossip and fighting, but for the usual reasons people get into conflicts. There have been some ethnic types of conflicts in the years since I left, more of a rift between the traditional Nepali people of the hills and the Indian-adjacent people of the terai. There is still discrimination against lower caste Hindu people (granted: not as openly disrespectful as it used to be, like throwing money at people or making them wash their own dishes). The status of women is still pretty low by Western standards – but most Nepali women I encountered felt pretty free compared to women in Muslim countries.

At the time I was in Nepal – the late 90’s – it was among the 10 poorest countries on earth. Its status has improved slightly since then. Tourism has something to do with that, of course. Another huge factor is remittances. Sadly, for most Nepali people, the best career opportunities are overseas, and most people who have any wealth got it from working overseas for a number of years. And I’m not talking about professional jobs – I mean doing the lowest, dirtiest work for wealthier countries.

Perhaps you’ve heard of the British Gurkha soldiers? Great Britain recruits men from the Nepali hills every year to serve in their army. They get lower pay and always get the harshest, riskiest assignments. But that low pay can turn around life for a family in Nepal, bring them from poverty to wealth (by Nepali standards) in a few short years. They have a well-deserved reputation for bravery. The British recruiters make Nepali men who want to join pass through a grueling physical test. Only a tiny percentage of the interested candidates are selected, and the British more or less openly discriminate to only allow certain ethnicities to be selected.

The British have been recruiting Gurkha soldiers from Nepal for going on for 200 years. When the British could not conquer Nepal when they tried to invade from colonial India, they decided better to recruit those fierce fighters from Nepal rather than fight against them. (Nepal is one of very few countries that was not colonized in the 17th to 20th centuries.)

Several other countries recruit Nepali men for their tough jobs, such as the Singapore police, construction jobs in the Arabian Peninsula, even fruit picking in England. You may remember the scandal of slavery-like conditions and large numbers of deaths of workers building World Cup stadiums in Qatar – many Nepali men were the victims.

And as horrific as many of these jobs are, these are the dream jobs – the ones people want and work their asses off to get. Working in Nepal, the options are not great. When I worked for the District Development Committee in Taplejung, which was kind of a combination governor’s office and public works construction agency, my boss was a Nepali man who got his Master’s at Cambridge (yes, that Cambridge). His monthly salary as one of the highest government officials in the state was 5,000 rupees (about $75 US). As a volunteer, I was considered not to have a salary, but the US government gave me an “allowance” of 7,500 rupees a month (about $110 US). Yes, the inequalities were tremendous and hard to rationalize on a moral basis, even if I could understand the economics.

Even at that paltry pay, my boss had just about the best job you could have in Nepal. The average worker subsisted on less than $1 a day, doing grueling work.

Since Nepal is so mountainous, many places are not accessible by vehicle. Heck, when I lived in Taplejung, the road was being built, and I had a 6-hour hike from the end of the passable road to the city – and it was the capital of the state. So without roads, workers have to carry everything on their backs, through steep and difficult terrain. I knew a guy in Taplejung, probably not even 45 kilos himself, who had carried a 100-kg load for 6 days to the most remote village in the district – it was part of a small hydroelectric station for that village. Porters get paid by the kilogram, so they often take on loads no human should endure. If they split the load with another guy, they get half the money.

And again, the porters may have been lucky compared to subsistence farmers. They basically function outside of a cash economy, growing what they can on land that is steep and difficult to manage, bartering for the few items or services they cannot live without, hoping to grow enough food they can survive another year. As soon as children are able to help (usually around 4th grade), they get pulled out of school to keep the farm going.

This was probably the hardest thing about my two years in Nepal. You see so much struggle, starvation, and misery all around you, and you have such a position of privilege and power based on nothing more than the country you happened to be born in.

It really ate me up. There was only so much I could do as a Peace Corps volunteer, and it amounted to a raindrop of help in an ocean of need.

There is so much more to cover, but I’ll stop here for now. I’ll get more into specific and colorful stories in future columns.

Pheri bhetaula (Talk to you later)

Let the author know you liked their article with a “heart” upvote!

Wow. So much to digest here, Pauly. Thanks for the eye- and heart-opener. It’s stunning, in every possible meaning of the word. That picture of the man bearing that load says volumes.

Yeah Chuck, this guy in the photo isn’t some extreme example either. If you live in the hills in a town with no road, that’s a daily sight.

I will say the road system has expanded considerably since I was there. I heard that very remote town 6 days’ walk away now has a road connected to it. There are still places with no motor road, but far fewer than there were 20 years ago.

Lovely post, Pauly. It sounds like this was a completely life-changing experience, and you paint such a vivid picture from your memories.

It seems that, generally speaking, rural/urban tensions can arise when there are increases in mutual awareness among these regions and their differences in lifestyle and outlook. The urban areas deal with diversity every day and adjust their lives accordingly (training for tolerance, but also possibly selecting for more novelty-seeking people), while the rural areas tend to be more homogeneous, tight-knit, cohesive, and wary of outsiders.

In America, the tension seems to have come from increased awareness via television and online media (and also talk radio). I don’t know the technological/media situation in Nepal or its history, but I imagine increased urban sprawl and perceived encroachment upon a cherished way of life is another surefire way of lighting these tensions. It’s the age-old problem of human tribalism, tailored for the modern age (or postmodern, in our case).

I didn’t see that so much. While I was in Nepal, parts of the country were deemed off limits by the US embassy because there was a Maoist insurgency going on. At this point the insurgents have become a political party and that fighting is long done.

Every urban Nepali person has family roots somewhere (almost certainly rural) and they identify that as their home. So it’s more like urban and rural are intertwined, not really in conflict.

Granted my 20+ year old perspective is likely out of date, but it seemed to be a very different dynamic.

Ah, I was riding off your comment about a “rift between the traditional Nepali people of the hills and the Indian-adjacent people of the terai,” but maybe I misunderstood.

That was more of a nationalism theme… people perceived as foreigners “taking our jobs”. Many of those “foreigners” have lived in Nepal for generations but don’t speak Nepali. They created their own political party, and have a goal of the south of Nepal seceding to become part of India. Up to a point it’s kind of reminiscent of the way Latinos in the US are treated, but if the Latino population wanted Texas, Arizona, New Mexico and California to rejoin Mexico.

Yeah, that’s one variation of the general trend I’m talking about. I would be happy to try to unpack my general understanding of this pervasive dynamic some time, and specifically how it relates to psychology….that is, if mt58 is okay with my wading into political waters. 🙂

Thank you for sharing this Pauly. I have to admit that Nepal wouldn’t be my place to go, but you gave us an interesting perspective.

Great read Pauly. Really good to get this perspective that digs deeper and shows there’s a lot more to Nepal than just mountains. Look forward to hearing more.

Pauly, I loved this. Absolutely the kind of cultural, geographical and social insight onto another country I love to learn about.

Can’t wait for next chapter!

I thought you may appreciate the terraced fields as topo lines concept… it’s like a living map! And when you fly over the hills and see it in relief, it’s a sight to behold!

I most definitely appreciated the topo map reference. 🙂

Terraced farms are beautiful in every way; visually they are just stunning in contrast to their surroundings. I once worked on a map that was created from stereo imagery in that region of the world, and I was constantly getting sidetracked just panning around the imagery and enjoying the 3d immersion in flying over all these terraced rice farms.

Ditto what dutchg8r said. I hope that between all of us we eventually cover all the countries in the world. Who wants to explain why The Gambia is basically just a river in the middle of another country?

I’d definitely be up for more of these types of articles. It’s a real gift to learn about another culture, and you can share that gift.

The Peace Corps mission is 1. Teach them about us. 2. Teach us about them. 3. Help them out. (I’m paraphrasing a bit.) Cultural exchange is 2 out of 3… you can spend 2 years in PC and not get one tangible thing accomplished and still get a passing grade with the learning and teaching about culture.

Anybody out there, any opportunity to get out of your comfort zone and experience another culture is a life changer.