I recently spoke of my final days in Nepal and my return to the United States.

But now, as Paul Harvey used to say, I will tell… the rest of the story.

About a month before my tour in Nepal ended, my 15-year-old brother came to visit me. This is honestly the biggest story of guts from my brother – and my parents.

You see, I knew my parents would not be able to handle Nepal. Maybe they could swing Kathmandu or Pokhara if they booked very tourist friendly hotels, but they could not visit Biratnagar or certainly not Taplejung – it was a bridge WAY too far. The food, the toilets, the non-stop walking – while my parents were not elderly or infirm, I just had a sense that it was way too much to ask. So I did not invite them to visit.

But my brother was in high school; he was an athlete. I figured he could handle it just fine. So I invited him. And to my surprise: my parents agreed. We planned for him to fly out to Nepal for two weeks – on his own!

Keep in mind that this was before any of us had cell phones, so my parents sent me an itinerary by e-mail, and I went to the airport to pick him up. But there was no communication in the interim. Honestly, I would be very hesitant to send my own son on such a voyage. And whatever I think about my brother, taking this trip took major huevos!

His flight arrived and there he was, emerging from the airport in Kathmandu. I can’t tell you:

(a) how happy I was to see my brother there in one piece, and…

(b) how jarring it was seeing my old life and my current life in the same space. My Nepal life was very separate from my previous life in the U.S. All my friends were different, my life was different in every way. Pretty much the only communication I had with home was letters (actual snail mail – remember those?) which took 3 weeks to reach their destination in the best of times. I could e-mail when I was in Kathmandu, so it was sporadic.

(Side note: I once got a card from my aunt for Thanksgiving, but she mentioned something about Christmas. I was like, that’s weird for her to be talking about Christmas already, then saw it was postmarked 10 ½ months earlier. She wrote it to me the previous Christmas!)

I planned to give my brother a 50% fun tourist experience and a 50% “real Nepal” experience.

I took him on a flight to see Mt. Everest, we went white water rafting, and we visited Swayambutnath (famed monkey temple in Kathmandu) and Patan Durbar Square.

Then for the “real Nepal,” we spent a couple of days on a bus, then spent 2 ½ full days walking, so I could take him to Taplejung. This was also less than a month before I myself was departing Nepal. So I was not only showing Taplejung to my brother, I was also visiting my friends for the last time, and saying goodbye. This sort of split attention on my part may have not been a great experience for my brother (since my friends spoke no English, and I was speaking Nepali with them, then translating for my brother).

I remember when we were on the 2 ½-day hike part of the trip, my brother was eating hardly anything.

He would barely touch his daal bhaat. When we stopped in a village and I found a place that sold eggs and ramen noodles (not common in really remote placed like this), I’d order large quantities of both for us to eat – both stir fry and soupy noodles, and both boiled and omelette style eggs. But he would barely touch them. When we finally got to Taplejung, and we were eating at my friends’ house, I explained to him that it’s rude to leave food uneaten on your plate. He still mostly played with his food and tried to “hide” his rice in the bowl of lentils. The only thing I could get him to eat was sekuwa, like a marinated meat snack you could occasionally find.

After a couple of days in Taplejung, we left and flew direct to Biratnagar. I think he was pretty terrified on the 20-minute plane ride. The sight of the plane landing on a grass air strip cut out of a mountain side probably was more than he was prepared for. (It’s now paved, but it wasn’t at that time.)

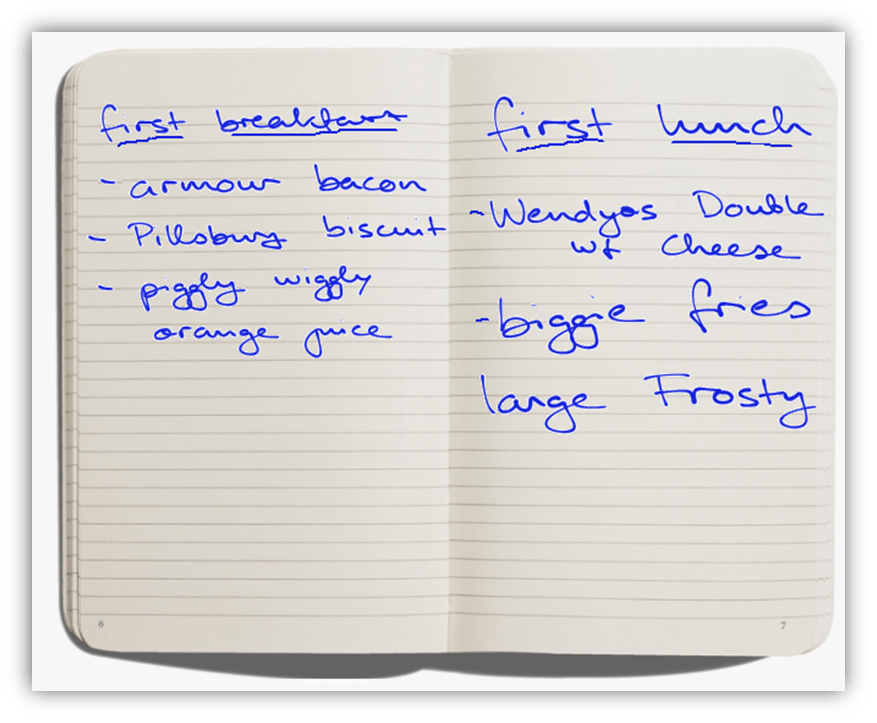

By the time we got to Biratnagar, he was suddenly inspired. We were riding a rickshaw from the airport to my apartment, and he got out a pen and a notebook and started writing feverishly. I was thinking, yes! He finally is starting to click with Nepal, curious, writing observations – something. I looked over his shoulder and it said,

Here my brother was in a foreign country on the opposite side of the world, and all he could think about was what meals he would have when he got back. And not just the food, but very specific brand names and everything. There was plentiful food in Nepal, and I was going out of my way to find the best options available, but he wouldn’t even try most of it.

He was not having a good time – suffice it to say he was fairly miserable.

Honestly, I don’t think he was enjoying the “touristy” part of the experience, but then the “real Nepal” part of the trip was just too much. So he put himself in his happy place and fantasized about going back home. We celebrated Tihar in Biratnagar, with all the lights and fireworks (the Indian equivalent of Tihar is Diwali), but his mind was somewhere else entirely. He was just enduring the trip, waiting for it to end.

And once he was back home, he rode the “15-year-old went alone to Nepal” cool factor for all the mileage it was worth.

He was something of a hero in his small-town Kentucky high school, bragging about his Nepal exploits as far as it would carry him. Only I knew that he didn’t enjoy it one bit, that his trip was pure misery for him. And not because I didn’t go out of my way to show him a good time or take care of him and make him feel safe (well, relatively so anyway), but because he was NOT OPEN to the experience. He got what he wanted out of it, which was status among his peers, and nothing else.

Of course, I didn’t expect him to “get it” in just two weeks, but I hoped at least to pique his curiosity about the outside world. I had hoped that maybe seeing the “real Nepal” – the way that people live, what they eat, how they live their day-to-day lives – may open up some tiny bit of empathy or curiosity in him.

On that front, I failed quite spectacularly.

This story is the preamble to my story of returning home, which I did less than a month after my brother flew back home from Nepal.

I was kind of excited and nervous about going back home – good meals, seeing friends I hadn’t seen for a few years, spending the holidays with family. I planned my arrival to surprise my parents and grandparents for Thanksgiving. I was surprised at how quickly that day went from excitement and hugs to following the same routine we did every Thanksgiving.

I started visiting my pre-Peace Corps friends, from high school, college and grad school days. Or trying to visit them, anyway. Some of them completely fell off the map (never wrote me once), and I had no way to get in touch with them. Others I hung out with, but they wanted to do the same stuff and talk about the same stuff – which is cool, but I mean to the exclusion of any “Nepal talk.”

If I brought up Nepal at all, I got the glazed look and a quick change of subject. Nobody seemed particularly curious about my experience. Many people wanted to praise me, like, “What a wonderful thing you did!” but they didn’t really care to hear about it. Or if anything, they just wanted to hear the lurid details (like toilet stuff), not the human side of the story.

My parents’ friends threw me a party a couple weeks after I came back. I should be grateful – it was a huge party. It was 30 or 40 of my parents’ friends, a few kids my age who were their children (none who were still my friends), and a few of my favorite high school teachers.

Were it not for the teachers – who showed genuine interest in my experience – the party would have been a total nightmare. Everybody wanted to come up and congratulate me like I came back from a warzone or something. But they didn’t care to hear about it AT ALL.

I remember at one point at this party, and I will never forget this as long as I live, one of my parents’ friends came up to me, whacked me on the shoulder, and said, “Welcome back to the real world.”

I immediately said, “This isn’t the real world. THAT’S the real world. This is a fantasy land.”

And without missing a beat, he said, “No, this is the real world,” and he walked away.

And this guy said honestly what everyone else was thinking.

The realization smacked me like a ton of bricks.

One of the three missions of the Peace Corps is to teach Americans about your host country.

Obviously, I can’t make people experience what I experienced, but you can’t teach people who don’t want to learn. And I’m not talking in-depth knowledge about Nepal, I’m talking very simple, basic stuff. Nobody gave a DAMN. Everyone wanted to congratulate me and move on, nobody wanted to know what I did, how Nepal had changed me.

The other thing that shook me pretty badly was how different my day-to-day life was. Going to Wal-Mart was truly an anxiety-inducing experience. The large, brightly-lit but sterile vibe was so inhuman. I was used to buying vegetables from people in an outdoor marketplace, where you talk to them and haggle prices. Stopping at 10 different places (one for veggies, one for dairy, one for meat, one for dry goods, etc) where you know the person selling you stuff. Walking there and walking back and seeing friends along the way and saying hi.

Now driving to a Wal-Mart, filling up a shopping cart with pre-packaged products and checking out seemed so impersonal, so fake. The bright lights made me really feel ill, and it took me several months to feel normal again in this type of setting.

This is a common experience among most Peace Corps volunteers – it’s called “reverse culture shock.”

You go to a foreign country, and you experience culture shock when you see the reality of how people in that country live. But then over time, you get used to it, maybe you even see some ways that it’s advantageous to the lifestyle you had before, and it’s not shocking, it’s just normal.

After two years, it becomes your life, for better and for worse, but you have to accept it wholly into your life or you have to quit and go home – they sure aren’t changing for you.

Then after being fully comfortable with this different culture, you return to your original culture, and it seems foreign. Things you never ever thought twice about are suddenly in your face, representing a stark contrast from the life you were living overseas. I never felt weirded out about Wal-Mart before Nepal; it was normal as breathing air. Now it felt not just weird, but downright hostile. My pulse quickened and I felt on edge – not just in Wal-Mart, but in most any public space in the United States.

I can honestly say that my reverse culture shock was worse than my original culture shock in Nepal. I had returned to the United States. I was trying to fit in and have a good time, but it seemed like everybody only wanted to deal with me on THEIR terms.

Nobody wanted to have anything to do with a Pauly who was transformed by this amazing experience; they wanted the old Pauly.

Preferably an incarnation of whom who would just shut the f- up.

It was very alienating.

I felt so lonely, so lost.

I started applying for jobs so I could get away from Kentucky and start fresh somewhere else. I thought if I went to a new community, I’d find some nice, open people and make friends, like it was so easy to make friends in the Peace Corps.

Once I finally found a job and moved across the country, I did get a chance to start fresh. But after I got to this new place, the people were largely the same. Very invested in their lives and uncurious about anything outside their worldview. I guess it’s the American way – blinders to the world, take care of your own ass and f- everybody else.

My two years in Nepal made me forget that. And the rude awakening was pretty harsh.

I emailed my Peace Corps friends to commiserate, and soon started making plans to visit them. I think most of them handled it better than I did. Several of them visited me (when I was living in the middle of nowhere, so God bless them for making the journey), and I visited many of them, all over the country. Every chance I had to take a vacation, it was to spend time with my Peace Corps friends. Of course it wasn’t exactly the same, but it was still comforting.

I should have seen my brother’s visit as foreshadowing for what was to follow. He came to Nepal, but with zero interest in learning anything, just an achievement he could ride for some version of street cred. Everyone expected me to bring the same attitude – I’m going to cash in this experience for something of value, rather than seeing the experience itself as the most valuable thing Nepal could give me.

Nobody wanted to learn about Nepal (ok, kind of not surprising), and nobody cared to learn how I had changed.

This one hurt.

After a couple of years, I finally met someone who was curious about the world and loved hearing and telling a good story.

She would go on to become Mrs. Pauly.

She had also lived abroad for several years and been permanently changed by the experience.

She was also kind of shunned by her family and friends for having had this experience. Though our experiences were different (she had lived in Europe), we definitely recognized in each other people who were permanently marked by this experience, and alienated from our family and friends who did not give a shit.

We became our own support system, and we will remain so.

So understand, this is not a sad story. Like any transformation, you lose things of value to gain things of greater value. Over time (for reasons beyond just Nepal, but which I won’t be delving into today), I’ve become estranged from my family with the exception of one truck driver cousin I still keep in touch with.

But MY family (meaning my wife and son) is the center of my world.

It’s a beautiful world we inhabit. We love, respect and protect each other.

My life is full. And my Nepal experience is a permanent part of my identity.

Let the author know you liked their article with a “heart” upvote!

I’m glad you’ve found a family where you feel listened to and belong with. I can empathise to an extent on the culture shock of the return home but for me it was only a year away and as the last part was spent in Australia it wasn’t so different in terms of culture and amenities. I had people that were interested in hearing about it, not everyone but enough of an outlet to not drive me mad. I remember after landing back in the UK being sat on the tube heading across London as everyone else went about their daily business and I desperately wanted to strike up a conversation with a stranger and tell someone, anyone about what I’d seen and done for the past year.

I can appreciate how infuriating it must have been for you to come home with a changed perception and have those closest to you just deny the experience at all or have such an insular and limited mindset that they can’t accept that their reality isn’t shared by everyone. If it helped you realise that you belonged somewhere else and to then find the people you needed then I guess it worked out OK in the end.

Makes me appreciate veterans even more, especially those who serve in combat. Imagine that same dynamic, but over a true life-or-death — not just an experience — but daily reality. Then coming home to Wal-Mart and uninterested friends and family.

It’s no wonder so many veterans have mental health repercussions from their service. (And for what???? But that’s another story and certainly not the veteran’s decision. )

This is an exceptional piece, Pauly. Kudos to you and Ms. Steyreen.

It drives me crazy when Americans go to Europe or Mexico on a package tour and come back thinking they’ve seen the place. The way to see a place is to visit the tourist attractions on the first day, then get as far from them as you can on the second day and live there for a while. Live like a local. Get to know people.

Like the Amish send their young adults away for a year to experience the world, all young Americans should do a year abroad. You don’t know a place until you’ve been somewhere else and none of us have the right to say we’re the greatest country in the world until we’ve lived somewhere else..

100% agree. Israel does this — lots of young Israelis go to Nepal, they can stretch their money a lot further there. I wish everybody did some sort of national service for at least a year. Go overseas or to the inner city or a rural town — get out of your comfort zone and live among people different from yourself. Not as a tourist, but working and living alongside the local people.

I just wanted to throw in a quick thank you for a terrific series. I had the pleasure of seeing it a few days before publication, while I was formatting. I think it’s great how you spoke from the heart.

Take a victory lap. I think that you ended it up beautifully… “on a mountaintop”.

Thank you, o gracious host! And thank you for adding the pictures and formatting to help make the story pop!

Most importantly, thank you for creating and maintaining this site, this labor of love. This is the little utopia I was longing for back when I came back from Nepal. A place with open-minded and friendly folks who like sharing stories to talking about random topics without agression or judgment. And thegue… lol! (J/k buddy)

Great writeup, Pauly. There is a lot that I can relate to, despite having quite different experiences.

My cultural adaptation in Tokyo likely wasn’t as dramatic as yours in rural Nepal, but it brought challenges all the same. And going from the hustle and bustle of modern Tokyo back to life in Philly wasn’t a 180 degree shift by any means…but, there was reverse culture shock all the same.

It was in Japan that I learned the collectivist proverb: “The nail that sticks out gets hammered down,” but I didn’t really feel the proverb until I came back. People were happy to have me back…so long as I shut up about life elsewhere and just got back to normal, everyday living.

As for me, I was inspired to take a job as a student study abroad advisor at my university, so I latched onto a community that “got” it. Plus, I returned from abroad right around the birth of Facebook, so soon enough I was back in contact with my Tokyo Japan buddies from all around the world. Not the same as in-person contact, of course, but better than nothing. Without those outlets, I would have felt really alienated.

Beyond that, there is another type of alienation that you allude to. Recently, my wife and I returned to Montreal, where we had once lived. It made us realize how much we miss about the place: the people, the pace of everything, the priorities…completely different from the greater DC region.

A lot of it is structural. If you want people to interact and socialize, you need to build social spaces conducive to meeting, playing, chatting, etc. Nowadays the main “social” spaces are stores–the US by and large doesn’t prioritize community anymore.

Some places are better than others–I sure miss my place in the highly walkable Old Town Alexandria, much more conducive to meeting and chatting than my current suburban abode–but pretty much every place I’ve visited prioritizes individual consumerism over community-planning. Much more than Montreal, anyway. Of course, they complain about how things have changed too, so it’s everywhere to some extent. #ThanksReagan

Thank you Phylum!

We as a country have made our mission to squeeze a dollar out of every interaction, institution, and relationship. So few public spaces exist outside that context (and many of the ones that do exist are poorly maintained). And because Americans are so insular and closed to the outside world, there aren’t enough people fighting for a more humane society, because they don’t know anything else is possible, they haven’t seen a different example.

I wish I knew an answer, but it has to start with a drastic change in priorities. I think a lot of people feel alienated and suspect things could be better, but either are too fearful of change or feel impotent to make any impact. That’s not just a coincidence. Those in power want others to feel powerless, helpless to change the status quo.

Anyway I’ll get off my soapbox. Nice to know there are other folks who get it!

It shouldn’t be a soapbox, what you’re preaching, Pauly, being a global citizen, but alas, a soapbox is required. You set a tone of benevolence for this site that I will surely aspire to.

It sounds as if your younger brother never experienced Cup o Noodles. What I like to call the “starter ramen”.

Where I live, there are people who have no interest in, not just the world, but the continental United States, which made me stick out like a sore thumb at my old job.

Great collection of comments, everybody.

Hi, Pauly. This was such a well-done piece — I can certainly understand how disorienting and frustrating this would feel. I’m glad you were able to co-create a different experience with your spouse and child.

As you were explaining it, your experience resonated with me, even though I have not had the experience of long-term exposure and adjustment to another culture/land. There’s something about coming out to one’s family and friends that involves a similar dynamic. Often, folks are fine remaining in relationship with you, as long as you remain the version of you that they loved/befriended and as long as the topics of conversation stick to the past or to the benign but never to the third rail of what you now know to be true. And it hurts when you recognize or even point it out and hear … crickets (or worse).

Anyhow, lots to ponder, and thank you for providing the opportunity to do so.

Chuck, Mrs. Pauly and I are honored to be mentioned in the same conversation as your marriage. From what I can tell from your posts, you and your husband have the kind of loving and supportive relationship all couples strive to achieve.

Our strategy is to stay away from the naysayers and negative Nancys. If someone doesn’t appreciate us — individually and as a couple — then that person does not fit in our lives. Even if they are family. Especially if they are family. I hate that my own family could be so dreadful to my wife and son to force me to choose between my wife and son and my birth family, but the choice is not hard. Quite easy really, and their loss, not ours.

Pauly,

I completely understand, though my experience was very different than yours. Before I moved, my stepmother cried and told me they “kill people like you there”. My cousin told me not get AIDS.

I moved to the Middle East.

I was also paid a lot of money to work there, so I was separated from true locals… but no one ever came to visit. Ever.

When I returned home, my parents left me a few brochures on my bed which called Islam the Devil’s Religion.

What I learned in my travels (35 countries, 48 states) is that people are the same. We are social creatures, and only politics and religion get in the way.

And my goal for my children is to never grow up in that bubble.

I’m standing up and applauding for everyone in this comment thread.

You folks get it.

Just amazing. Good on you all.

I remember making that exact observation to one of my (former) best friends right after I returned from Nepal. I was like, “People everywhere are the same, it’s just culture that makes a difference.” I got an eye roll and a change of subject. It doesn’t make any sense if you haven’t seen it, but it’s so simple too. Culture and religion create identity based on differentiation. People lean into the differences to feel like part of the tribe. But we are really all humans, with fears, love, curiosity and pain, with so much more in common than we have different.

In a separate conversation with a Peace Corps volunteer, I observed that the things that all religions have in common are the closest thing we have to a universal truth. Every religion has a version of the Golden Rule for example. Why don’t we lean into those similarities rather than the differences (which animals you’re allowed to eat, or other arbitrary rules)?

Answer: religions don’t get followers, money or power from leaning into the sameness. They get power from differentiation. Stay in the flock, stay away from those heathens. Only Jesus (or Buddha or Mohammed or whoever) can show you the way to a happy afterlife. Today we call that building brand loyalty. I think the era of that type of thinking should be abandoned to the past. Got NO problem with any person following their religion, but respect the other guy/gal too. Their beliefs are just as valid as yours (unless that person is a scientologist LOL).

Thank you, Pauly:

I know this should go without saying, but I think if it was a tnocs.com get together, you might actually get tired of talking about Nepal with us, Pauly! We’d ask soooo many questions… 🙂

And kudos to you in finding likeminded Mrs Pauly. No doubt youngling Pauly Jr will never have to worry about his desire to explore being stifled.

It’s a subtle decision parents have to make – have their life now revolve around kids once kids are born,

OR,

continue to live your life with your spouse, and the kid comes along for the ride.

It definitely impacts that child’s view of the world as they grow up. I was obviously in the Ride Along group, and I am eternally grateful to my parents for having that approach, because it bolstered my independent spirit.

I’m very sad our Nepal journey has come to an end, it was tremendous fun. And hopefully your brother has had 20 years of reflection and realized there were some cool aspects of his trip after all!

Thanks Dutch! I’m considering an “Odds and Ends” sort of extra piece around Nepal… little anecdotes or observations that didn’t make it into a previous article. But I’m not sure, and if i do, it won’t be too soon…

I have a very different idea in mind for my next article, should our dear leader mt choose to publish it. Not to spoil anything, but may be related to an event I’m planning to attend this weekend.

As for my brother, I have no idea is he had made any attempt at reflection, but I suspect not.

It’s my habit to be late to these articles but I wanted to put in a quick word and say I really appreciate your taking the time to share these wonderful experiences. The reaction of your friends and family is sadly not surprising to me. As a country, America seems to be really incurious. We’re taught from a young age that we’re the best and practically no one else really matters. I think your experience speaks to that. I don’t have kids, but I have a 4-year old niece. I trust my brother to raise her differently, and I’ll hopefully do whatever is needed to reinforce it.

As we remove ourselves from the center, we learn our true worth. We used to think the earth was the center of the universe (nope) or center of the solar system (also nope). We used to think white meant civilized and other races were savages (nope, kind of backwards). We used to think the earth would provide for us infinitely and we had no responsibility to take care of it (yeah right!) The more we see the truth without this dumb egotistical tendency to place ourselves at the center, the better we can understand and address the challenges around us.

Next step in the process… realizing animals have the same worth and same rights we extend other humans. We’ve got a long way to go on that one…

Thank you for reading and enjoying the stories. Take care bud!

not the american way, just the usa way.

and your friend feeling like he lives in the real world, he must be feeling a rude awaking now that the problems of the “not real world” are encroaching from all sides.

Loved the series, would like to go one day to take pictures. Also the food looked really good.

Thanks for the correction (though if you go to Nepal, everyone uses the term “American” to mean the US… but I should know better!)

That guy is NOT my friend, he was my parents’ friend. He had kids close to my age who I was also not friends with. I am sure he has inhaled so many lies about the US that he will never see straight again. His opinions are less than irrelevant.