Okay, last time we did a deep dive into the first few verses of the Mark gospel.

We found that the author used subtle allusions to older Hebrew Scriptures in order to establish John the Baptist as representing “Elijah,” whose coming was prophesied in the book of Malachi to precede God’s destruction of Jerusalem as punishment for the sins of the people.

When Malachi was written, it was referring to the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem in 587 BC. Given that the scholars date the writing of the Mark gospel to the wake of Rome’s destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE, did the author intend this historic cataclysm to be the framing conceit of his story?

If so: He’s not very direct in stating that it is, so maybe we should explore the work a bit further.

Once Jesus returns from the desert, he calls three fishermen to be his disciples. He states that his intention for them is to be fishers of people.

In Sunday school, we often talked about, and sang about, the disciples being “fishers of men.”

That’s a good thing to be, right?

It’s about catching followers for the movement by making them believers.

Right?

Well, with respect to the Mark gospel, such a meaning is at odds with the exclusive and secretive manner of Jesus as written in the story.

There’s actually a good chance that this is another scriptural allusion. The only time the idea of fishing for people is raised in the Hebrew Scriptures, it’s a passage about God’s violent punishment of his sinful followers:

“But now I will send for many fishermen,” declares the Lord, “and they will catch them.

After that I will send for many hunters, and they will hunt them down on every mountain and hill and from the crevices of the rocks.

My eyes are on all their ways; they are not hidden from me, nor is their sin concealed from my eyes.

I will repay them double for their wickedness and their sin, because they have defiled my land with the lifeless forms of their vile images and have filled my inheritance with their detestable idols.”

Jeremiah 16: 16-18

Remember when Jesus refused to explain the meaning of his parable to the larger crowd, and only explained the meaning to his twelve disciples? As his justification, he says “so that they might be ever seeing but never perceiving, and ever hearing but never understanding. Otherwise they might turn and be forgiven!”

This is actually taken from Isaiah, and points to a larger passage about the destruction of Israel as punishment:

“Then I heard the voice of the Lord saying, “Whom shall I send? And who will go for us?” And I said, “Here am I. Send me!”

He said,

“Go and tell this people: “`Be ever hearing, but never understanding; be ever seeing, but never perceiving.’ Make the heart of this people calloused; make their ears dull and close their eyes. Otherwise they might see with their eyes, hear with their ears, understand with their hearts, and turn and be healed.”

Then I said, “For how long, O Lord?” And he answered: “Until the cities lie ruined and without inhabitant, until the houses are left deserted and the fields ruined and ravaged, until the LORD has sent everyone far away and the land is utterly forsaken.” (Isaiah 6:8-12)

The Mark gospel has embedded within its story several other such allusions to scriptures about destruction and punishment. A lot of those weird and otherwise inexplicable details in the story are in fact scriptural allusions.

Remember the fig tree being cursed right before Jesus clears the Jerusalem temple?

Remember the fig tree being cursed right before Jesus clears the Jerusalem temple?

It recalls Hosea 9, a passage about destruction as punishment. Forcing Jesus to drink wine after he consecrated himself, and a naked man fleeing? Check out Amos 2, which also happens to mention selling the righteous for silver. And it’s about destruction as punishment. When viewing the Jerusalem Temple, Jesus quotes Daniel 9 as well as more allusions to Isaiah, all relating to invasion or destruction.

There might be some other ones that I’m missing.

Surely Jesus’ parable about the vineyard owner killing the tenants and giving the lands to others was about violent retribution as well.

I think we can be fairly confident that the author was trying to seed ideas about destruction as punishment for the sins of the people as a central conceit of his gospel story, yet he hid those ideas in obscure allusions.

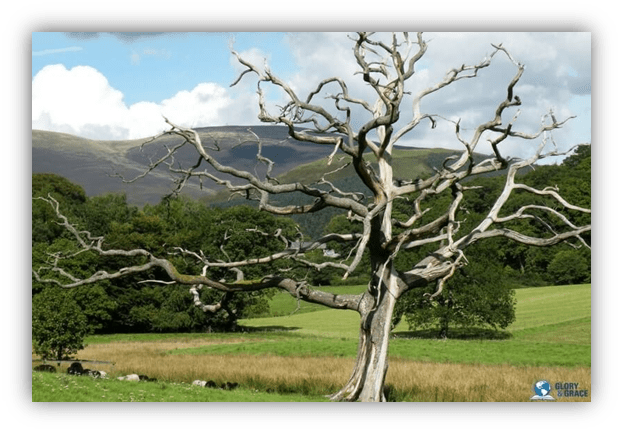

Make no mistake about it, the gospel of Mark is quite a dark work.

Given its time of writing, that really shouldn’t surprise us. The destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE was a cataclysm of unimaginable proportions.

For the Christians and Jews of Judea and surrounding lands it was a world-shaking event. It makes perfect sense that someone writing in the wake of such desolation and loss would try to make sense of the tragedy—and do so in a way that expresses deep anger and frustration. Just like those older Hebrew prophecies, which tried to make sense of the earlier destruction of Jerusalem in harshly moralistic and judgmental terms.

In Jewish history, there is a long tradition of heated internal criticism, in no small part due to the centuries spent as tributaries and victims of various foreign rulers, with opposing factions arguing and fighting over what went wrong to make God want to punish his chosen people so. We’ll touch on that tragic theme later on.

Of course, there are plenty of other scriptural allusions in the story that are not about violent punishment or destruction. And we can look at those later to get a better idea of what exactly the Mark author was advocating and what he was arguing against.

We’ll get a better understanding of this severity and dark outlook of the author and the older scriptures he referenced; an understanding of the larger history and culture is essential to get a grip on where this worldview comes from.

But we’ll also see the light that emerges in such darkness.

The softness and grace within Christian tradition that inspires people to this day. We’ll get glimpses of that too.

Until next time...

Let the author know that you appreciated their article with a “heart” upvote!

This post and the last one were heavily inspired by The Gospel of Mark as Reaction and Allegory by R.G. Price. Price is an amateur scholar (and a bit of a cantankerous anti-theist), but his thesis is soundly argued and based on readily observable evidence. It was the first work I found that addressed all of the questions I had about the Mark gospel in a satisfactory way.

http://www.rationalrevolution.net/articles/gospel_mark.htm

I’ll touch on another in the next post.

I’ll always take a good book rec. Thanks!

He can be a frustrating read, I will say. He overstates his case sometimes, he lacks imagination on some aspects of theology, and he really needs an editor.

But, his core argument is solid. He saw something that most people did not.

There’s something poetically satisfying about the fact that this unpolished amateur scholar saw something in the scriptures that the established “priestly” class did not–for that is precisely what gave rise to apocalyptic readings of old scriptures in the first place! The written Torah and other works began to spread around, and people who broke away from the Temple priests began to read the scriptures quite differently, and a new cluster of theological beliefs and practices began to form.

Very dark indeed. That’s a great observation about fishers of men. Funny thought that occurred to me based on your comment: I think my favorite amateur Biblical scholar is Charles Schulz! I use a 365-day Peanuts calendar and the scripture-rated strips are almost always more incisive than any other content of that nature I’ve come across. He became a skeptic later in life but never lost his interest in the subject, much like many of us!

I guess I don’t know too much of Schulz’s take on religion beyond Merry Christmas, Charlie Brown (which is quite wonderful to this day). I’ll have to give it a look.

I like the gentle tone of A Charlie Brown Christmas. The characters don’t talk about God, but you can tell that they believe in him. If I was a Bible scholar, I’d probably be writing an essay about the symbolism of Linus’ blanket.

Vengeance and retribution – a tale as old as time it seems. Some of the speeches from Putin would seem to fit right in with the tone of those extracts speaking of destruction and punishment. Not suggesting he’s taking his cues from the bible but it evidences as a species that for all our advances in science, culture and understanding of the world we haven’t necessarily advanced much as people.

Certainly Putin does try to tap into righteous sentiments as justification for his actions, though it all comes off as empty cynicism to me. I guess it works on his more gullible supporters though, so it can have a similar effect.

The problem that plagues humanity at large is the sincere feeling of righteous indignation. And part of why it’s problematic is that it’s often justified to some extent, or at least relatable once you know someone’s perspective.

Psalm 137 is a famous snapshot of an exiled people held as servants in Babylon, and our compassion for their plight and their sorrow swells as we read the passage. But then that devastating final line hits, and we understand the depths of their rage: “happy is the one who seizes your infants and dashes them upon the rocks.”

Knowing that this is exactly what had happened to them doesn’t make it any less queasy, particularly because we know this “we didn’t start it, you did” mentality just goes on and on over the course of human history. It just makes it doubly tragic, and yet evocative of real human feeling, and predicaments that can sometimes shed light on our own.