“Question Mark,” Episode 5: Is Seven Greater Than Twelve?

In the last post, we explored how the Mark author wove together allusions to older Hebrew prophecies about destruction in order to frame his own narrative about the sins of the people of Jerusalem.

Some of those sins seem to have been a concern for traditional Jewish laws and customs, such as circumcision and food restrictions.

In this, the author was wading into a controversy that had raged within early Christian communities for some time. Should followers of Christ follow Jewish laws or not?

Everyone knows that Christianity was originally an offshoot of Jewish culture. Yet over time, the movement expanded beyond Judea and into the wider Roman Empire, and eventually it came to be dominated by Gentile converts.

For the Christians with a Jewish heritage, this situation imposed a real dilemma. Should you spread the word of Jesus in the most efficient way, and risk cultural erasure? Or should you work to preserve your identity and risk the movement’s stagnation, if not annihilation by the Romans?

There was no easy answer, but most felt compelled to pick a side.

Obviously, the Mark author sided with the more laissez-faire, cosmopolitan factions. Not only does he have Jesus declare obsolete the laws of kashrut (dietary laws, i.e., what is and is not kosher), he tells his followers to embrace anyone who evangelizes in his name:

“Teacher,” said John, “we saw someone driving out demons in your name and we told him to stop, because he was not one of us.”

“Do not stop him.“

“For no one who does a miracle in my name can in the next moment say anything bad about me, for whoever is not against us is for us.

Truly I tell you, anyone who gives you a cup of water in my name because you belong to the Messiah will certainly not lose their reward.”

Jesus: Mark 9:38-41

And yet, in the wake of Rome’s destruction of Jerusalem, that advocacy for openness over staunch legalism seems to have curdled into a cold contempt for those who had fought for Jewish traditions.

The author thinks that those Christians had set their minds on human concerns, not the concerns of God. And so in his gospel, he depicts the Jews and Jewish Christians of Jerusalem as inviting their own destruction, crucifying the messiah in the process.

Not only that, but he peppers his story with several indications that the good news of Jesus has or will pass from the Jews to the Gentiles.

Think back to the pig herder (a decidedly un-kosher trade) in a land outside of Judea: this is the one person he instructs to spread the story of his healing. Family and home are portrayed negatively several times throughout the story. While a Jewish Simon denies Jesus three times despite having been instructed to carry a cross for him, a Gentile Simon literally carries a cross for Jesus.

Then there is the Greek woman, whose daughter Jesus heals after she points out that the dogs (the Gentiles) eats the crumbs that the children (the Jews) do not.

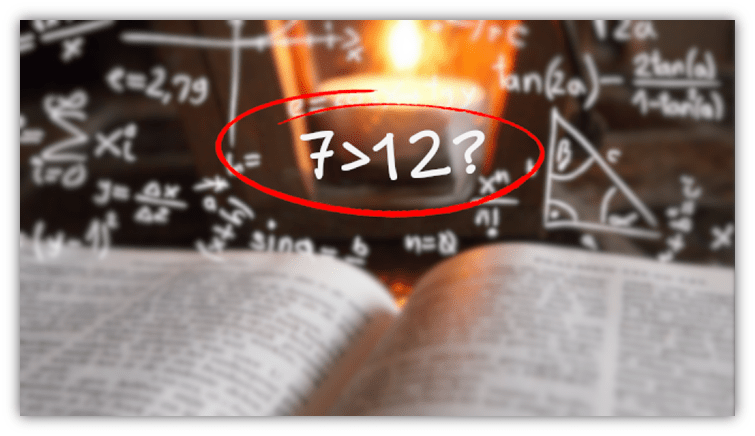

This scene is bookended by two miraculous feeding scenes: the first with 12 bread baskets and the second with 7 baskets.

Jesus suggests to his disciples that the number of baskets has some deeper meaning, but he leaves it unexplained.

The best guess is that the baskets represent the 12 tribes of Israel and then the 7 hills of Rome.

The children were fed first, then the dogs. And while the dogs appreciated what they got, the 12 children did not. Because, as the story indicates, “their hearts were hardened.”

Notably, even with this severe stance against Jewish traditionalism, the author shared some illustrious company. This whole controversy about law and custom in Christianity arguably started when the apostle Paul offered to dedicate his life to converting the uncircumcised to the movement around 50 CE.

Several of Paul’s letters describe heated arguments with rival Christian leaders pertaining to the correct practices of Christians regarding Jewish laws. And Paul could really bring the fire to his rivals in those letters. Just read his Epistle to the Galatians and see how he treats those “esteemed pillars” of the Christian movement: Peter, John, and James.

That one’s more passive aggressive than outright vicious, but it’s far more heated than what I had gathered from church sermons!

Maybe at some point they were all friends, but that friendliness had completely vanished by the time of Paul’s letter.

Speaking of those three apostles, there is actually quite a lot of material from the Mark gospel that may have been inspired by Paul’s letters. Those three individuals are distinguished in the gospel as Jesus’ main disciples, yet they are consistently depicted as foolish, and ultimately fail their messiah. Many of Jesus’ words of wisdom are in perfect harmony with passages that Paul wrote.

And clearly: both men advocated passionately for a pragmatic, open approach to Christian practice, both of them dismissing Jewish law as an earthly concern rather than a heavenly one. Maybe this is all coincidence, but for me it makes sense to conclude that the Mark author was a Pauline Christian, a member of one of the many communities around the land that the apostle himself had helped to establish.

Of course, while quoting and paraphrasing an older work is often a sign of admiration, it’s not always the case.

Especially when someone samples that older work and recontextualizes the content…in order to support the opposing side!

…to be continued…

Let the author know that you appreciated their article with a “heart” upvote!

Definitely well beyond my entry level bible knowledge now. It seems that rather than simply allowing for Jesus to lead by example in terms of this is the right way to live your life there was as much emphasis on contrasting this with Jewish ways and traditions. In essence the negative campaigning so beloved of many politicians – its often easier to rubbish what someone else stands for than to promote your own point of view.

Been listening to a podcast recently called the New Conspiracist which looks at a different theory each week, some more serious than others; from has April Lavigne been replaced by a body double to Russiagate. There’s a running joke that no matter how outlandish and unlikely it seems the Jews will crop up somewhere in the story as being behind it all.

Whatever the intention of Mark’s author I can see how the framing of Jewish practices has fed into that.

Yes, your last point zeroes in one something that I will touch on at the series’ conclusion: the use of mostly Jewish infighting by later Gentiles to justify anti-semitic sentiment and actions. Paul’s letters, the Mark gospel (and perhaps most of all, John) all played a role in that, unfortunately.

One other thing I’ll touch on in a later post is how Jewish apocalyptic traditions–including Christianity, but also the community that wrote and stored the Dead Sea Scrolls, and whoever wrote the book of Daniel–was largely a reaction to empires and foreign oppression.

The scholar Anathea Portier-Young argues in Apocalypse Against Empire that apocalyptic groups were essentially divided into two different types: the “zealots” who actively resisted against Roman rule, and the “quietists,” who retreated from the political world and simply dreamed of cosmic revenge at the end of days.

This feud in early Christianity between the “judaizers” and the more laissez-faire integrationalists echoes that broader divide between the zealots and the quietists. Because the Roman empire required assimilation, and Jewish tradition was long meant to set its people apart from those around them. Of course, any Christian community that let Gentiles enter would be a bit more inclusive than, say, the Pharisees and Sadducees, but strict enforcement of Jewish laws for Gentiles still sets them apart from the larger pagan culture–and setting the people apart was interpreted as a threat to Roman rule.

People like Paul and the author of Mark thought that if Christians simply disengaged from the politics of the day that the movement could survive and thrive. Ultimately, perhaps they were right, but I don’t think they thought through the costs of such a success. Still, I understand their feelings of frustration (as well as that of the opposing side) given such high stakes. And they do positively advocate positions and deeds as well, it’s not all attacks.

Now, as for the example of Jesus, it really remains an open question as to what that was, at least given the writings we have to work with. As we’ll see next time, he can advocate for positions that directly oppose one another…yet that reflects the various authors rather than the man they used as a moral authority within their writings.

Thanks for such an indepth response and the additional context. A lot to take in and think about. I’ve been to donate blood this afternoon so I’ll be honest, my brain isn’t functioning at peak capacity right now but I’ll definitely re-read this again tomorrow when I’m fully with it and can give it the attention it deserves.

Thanks for all the work you’ve put into the series. As ever, look forward to continuing the journey.

There is an ancient tradition in the church (going back at least to the second century, although there is some evidence that it was believed in the first) that Mark based his gospel on the sermons and recollections of Peter. Mark seems to have accompanied Paul on some of his evangelical journeys, but then gone back to Jerusalem, only to return to Paul after the death of Peter.

It has been suggested that Peter was very aware of his shortcomings and was very open about them.

Yes, that is part of early Catholic tradition, but to be honest I’m completely baffled by that interpretation!

Of course, if people were reading the versions of Mark with one of the two added endings, maybe it makes sense, since Peter is mentioned most of all of the disciples throughout the story, and everyone is redeemed at the end of those versions. But without that added content, Peter does not come out looking so good throughout or by the end of the Mark story.

If you’re interested, I recommend Tom Dykstra’s recent book Mark, Canonizer of Paul for a different take, one that informed this post. The title makes the nature of his argument pretty clear. 🤓

Let me know what you think!

Peter doesn’t come out looking very good. That is part of the tradition, that he was very humble about himself. The earliest mention of this theory was in the writings of Bishop Papias of Hierapolis who lived from about 60-130 AD. I don’t know that I totally ascribe to this tradition, but it is very interesting. It also reflects better on Peter (my personal favorite Bible character) to believe that he admitted to his own mistakes, rather than to have them told about him without his consent.

I’ll go into depictions of Peter a little bit more in the next post. And I think it will touch on some of what you’re talking about here.

I certainly would love to read a letter from Peter that goes into the scenario that Paul mentions in Galatians! The Luke-Acts author depicts a scenario that’s fairly conciliatory, but I don’t get that vibe at all from Paul. I think that later author was trying to resolve such arguments according to his own theology rather than depicting the details as they happened. Understandable, but Peter’s stance is left mostly unknown.

Paul does represent it pretty harshly, but he was a pretty unbending type. All that Pharisee training, I suppose.

Daaaaamn!