The authors of all four New Testament gospels borrowed story elements from older scriptures.

Additionally, the Matthew author sampled the Mark gospel for his story, and the Luke author sampled both of those gospels for his comprehensive take.

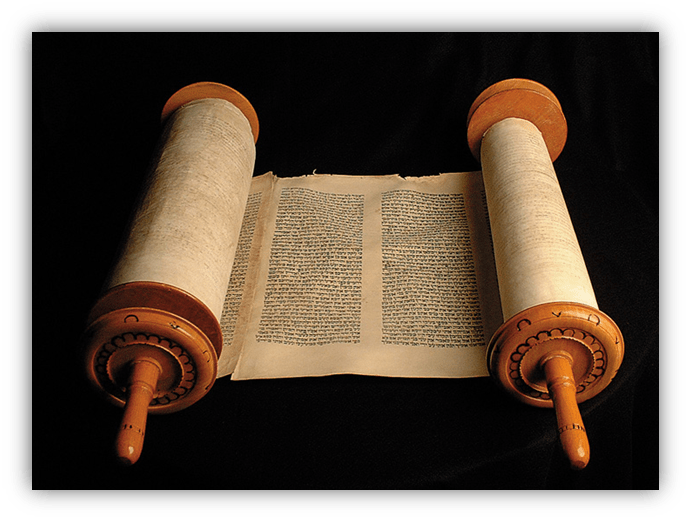

As mentioned in the previous post, evidence of sampling and revising older works goes back to some of the very oldest books of the Bible, including those of the Torah.

That’s nothing new.

What’s interesting, and perhaps new, is that the three later gospels stories are all based in some way upon the Mark gospel, which is itself a cryptic story, full of symbols hiding in plain sight. How much of this esotericism was common in early Christian tradition? And how much did those later gospel authors pick up on what the Mark author was laying down via subtle allusions and signifiers? Let’s explore.

First, a very brief top-level overview of Jewish history leading up to early Christianity.

Once the twelve tribes of Israel united into a kingdom, they enjoyed a few hundred years of relative peace and prosperity (even considering a split into two kingdoms), during which they cultivated the notion that they were the chosen people of God. But the next few centuries offered calamity after calamity, and continued subjugation by one foreign ruler after another: first Assyria, then Babylonia, then Persia, then Greco-Macedonia, then Rome.

Assyria destroyed the northern kingdom of Israel, and then Babylonian forces destroyed the southern kingdom of Judah. At that point, the survivors were scattered across the lands. Many returned once the Persian king Cyrus granted them the territory of Judea, and they were united under the laws established by a newly revealed authoritative Torah of Moses.

Yet without a king to unite them, factions formed and fought about who should hold power and how the Torah should be interpreted.

Some groups broke away from the Temple authorities, formed their own small communities with strict rules for admittance, and followed charismatic leaders who espoused new interpretations of holy scripture based on personal revelation. These were the groups that are nowadays referred to as “apocalyptic.”

Now, when most people today say the word “apocalyptic,” they mean something like the end of the world.

But originally, “apocalypse” just meant revelation, the uncovering of truth that was hidden…

…the lifting of the veil.

The emergence of personal revelation to determine truths in the Hebrew scriptures led to beliefs in many new prophecies, even within works that were not formally considered to be written by or about prophets. Like, for instance, the psalms of David.

Of course, the apocalyptic communities did tend to concern themselves with the end of the world, which explains the association we make today. Over the course of centuries of foreign occupation, Jewish culture had become subject to outside influences, the two most important influences being Persian Zoroastrianism and Hellenism (including Platonism).

Both of these traditions framed the state of the world as heading toward a final end state; in Zoroastrianism, this is the day when evil will finally be vanquished. The apocalyptic Judean sects came to see their foreign occupiers as powered by evil beings such as Beliar, Beelzebub, and Satan.

Their lot in life had sunk so low that some decided to hunker down together in isolated communities, purify themselves by ascetic ritual, and wait for the day of judgment to signal their time of heavenly glory.

These communities did not simply interpret scriptures, they also wrote their own. Two of the most important works of apocalyptic Jewish tradition are the book of Enoch, and the book of Daniel. Christians today don’t have Enoch in their bibles, but many will recognize the narrative of fallen angels it established, because it was quoted in the epistles of Jude and II Peter.

Both of these scriptures discuss the end times, yet they do so using very striking and bizarre imagery, often heavy with symbolism.

These scriptures set the standard for literary apocalypses, a standard that the author of Mark sought to follow. Another work in this tradition is the book of Revelation; this too was heavily influenced by Daniel and Enoch, and this too features some cryptic details that bounce off our heads like seeds thrown at a melon.

As an example, take the number of the beast: 666. Scholars state that this is actually an alphanumeric code (common in certain strains of ancient Hebrew and Greek writings) for “Nero Caesar” in Greek. This Roman emperor was at that time infamous for his execution of Christians, and was regarded as a figure of evil in recent history. And also a symbol for Roman power more generally.

Like the older apocalyptic communities, the Revelation author linked the rulers of his days to the forces of evil, and he used cryptic symbols to criticize his oppressors with impunity. Yet most readers aren’t equipped to crack that code on their own, even other Christians.

Obviously, something shifted over time.

So we know that some early Christians were steeped in apocalyptic literary tradition and esoteric symbolism, but what about the authors of Matthew, Luke, and John?

That’s actually harder to say.

I think it’s somewhat of an intermediate case.

As mentioned at the start, they were on board with the tradition of weaving together narratives from various scriptural sources. Clearly, the Matthew author picked up on the Mark gospel’s opening reference to the Malachi prophecy, and his connection of that prophecy to John the Baptist as Elijah – we know this because he spells out the association quite explicitly in his text.

Yet this openly didactic approach, which is found throughout Matthew as well as Luke and John, doesn’t itself square with esoteric tradition. The authors seem to be people who are well versed in the Hebrew Scriptures, and perhaps on apocalyptic interpretations of those scriptures (such as their love of Psalms as sources of prophecy), but they seem to use their written stories to communicate to the broadest audiences possible.

This approach likely helped their gospels to spread around the Gentile world, but it seems to reflect a disconnect from older apocalyptic traditions. And there is evidence that they did not understand all of the references that were originally planted.

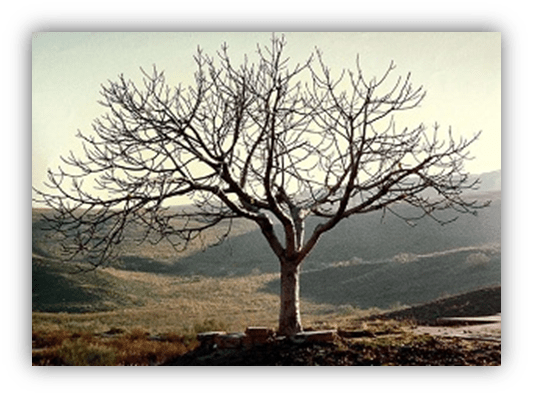

For instance, the Mark gospel has successive scenes of Jesus cursing a fig tree, clearing the temple, then seeing that the fig tree had withered, and together these all allude to Hosea 9.

Yet such an allusion is made less clear with Matthew’s truncated version of the scenes.

Seeing but not perceiving, perhaps.

So whose vision of the good news ultimately won out?

What did Christian tradition look like a century later? Two centuries later?

That will be the focus of my next and last post of the series.

Until then!

…to be continued…

Let the author know that you appreciated their article with a “heart” upvote!

Curiouser and curiouser!

I checked Wikipedia. The Book of Enoch is recognized by the Ethiopian Jews. This interests me. The Ethiopian Jews are mentioned in Uncut Gems. Okay. And “fallen angels” are mentioned in Enoch. Cool. I have my answer as to why Uncut Gems opens like a certain 1973 film. Do you think the premise of The Safdie Brothers’ film is based around The Book of Enoch’s exclusion from the unabridged text? The final shot in the film left me gasping. The camera goes inside Adam Sandler’s corpse, and you have a response to the call of the opening sequence; you see what possesses the jewelry salesman; the devil in metaphor, one of the seven deadly sins.

Okay. You told me you don’t watch sports. Kevin Garnett’s jersey number was 5 as a Boston Celtic, the team he plays for in the film. That’s not a perfect match; it’s the wrong deadly sin. But the right deadly sin that the Safdies are referencing was Garnett’s jersey number, #2, as a member of the Brooklyn Nets.

Fun stuff, Phylum of Alexandria. It allows me to wave my freak flag.

I haven’t seen Uncut Gems, but there’s plenty of freaky content in Jewish apocalyptic works and some early Christian stuff, particularly of the Gnostic variety.

Trying to suss out the codes and connections sometimes makes me feel like a second rate Dan Brown, or worse, a Q Anon adherent. But sometimes it’s best to sit in awe and just soak up the weird without wondering what it might mean.

Case in point, this verse from the Odes of Solomon:

Ode XIX

A cup of milk I was offered

and I drank its sweetness as the delight of the Lord.

The Son is the cup

and he who was milked is the Father,

and he who milked him is the Holy Ghost.

His breasts were full

and his milk should not drip out wastefully.

The Holy Ghost opened the Fathers raiment

and mingled the milk from the Father

s two breastsand gave that mingling to the world, which was unknowing

Those who drink it are near his right hand

The Spirit opened the Virgins womb

and she received the milk.

The Virgin became a mother of great mercy;

she labored, but not in pain, and bore a son.

No midwife came.

She bore him as if she were a man,

openly, with dignity, with kindness.

She loved him, and swaddled him, and revealed his majesty.

While I’m a practicing Christian, and I value the scriptures as a guide for my life and to understand God’s nature and purposes, I can appreciate your comment “… sometimes it’s best to sit in awe and just soak up the weird without wondering what it might mean.” I think that a lot of pop culture music and movies over the years have used apocalyptic scripture to this end. I think of this as I listen to the Peter Gabriel penned lyrics of Genesis’ “Supper’s Ready” (as in, the final supper–the second coming). It’s not a religious song, but it certainly uses all sorts of apocalyptic scriptural imagery to create a mood that is grand and majestic and mysterious and frightening.

I’m not conventionally religious, but Christian in my own way.

And one thing that annoys me about scholars’ obsession with the historical Jesus is their determination to turn the linchpin of the faith–its central mystery–into just some charismatic dude, essentially another John the Baptist. Even if Jesus was that dude, he’s not the Jesus that inhabits the scriptures.

Faith probably should be weird in some way, or else it’s indistinguishable from mundane and profane everyday life.