In 1971, DC Comics finally learned from Marvel and developed a long-form Batman story that continued over a series of issues.

This story was notably more mature in its themes than previous issues, introducing a complicated character who was both friend and villain to Batman.

Perhaps wishing to signal this newfound maturity, the comic changed its description of Robin from “The Boy Wonder” to “The Teen Wonder.”

Indeed, the kids growing up in the postwar years had since become adults. And beyond that, life had seemingly grown so much more complicated than ever before. It makes perfect sense that even vibrantly colored action panels would start to convey more shades of gray.

As for the adults, perhaps the stories that best reflect the changes of the time are works of dystopian fiction.

Dystopian stories often serve as warnings to readers of potential cultural dangers to consider.

Even as early as the 1920s and 30s, novels like We and Brave New World put their focus on dangers that were rather subtle and insidious in nature compared to earlier works, reflecting the increasing complexity of modern society.

Orwell’s 1984 was similarly sophisticated, starting with the hints of authoritarianism found in everyday life and taking them to nightmarish conclusions.

What about dystopian fiction at the start of the 70s? These stories not only pointed to new dangers to consider, they arguably reframed the whole purpose of the genre.

Here are three major works of the era, and how they reflected the strangeness of the time.

Real Horrorshow!

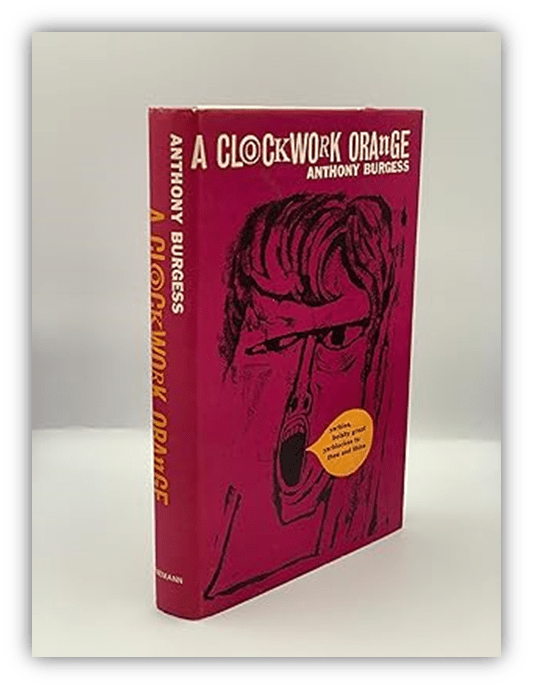

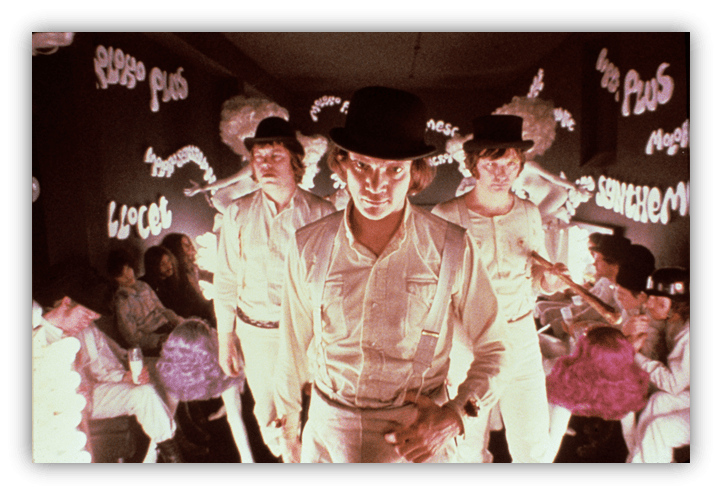

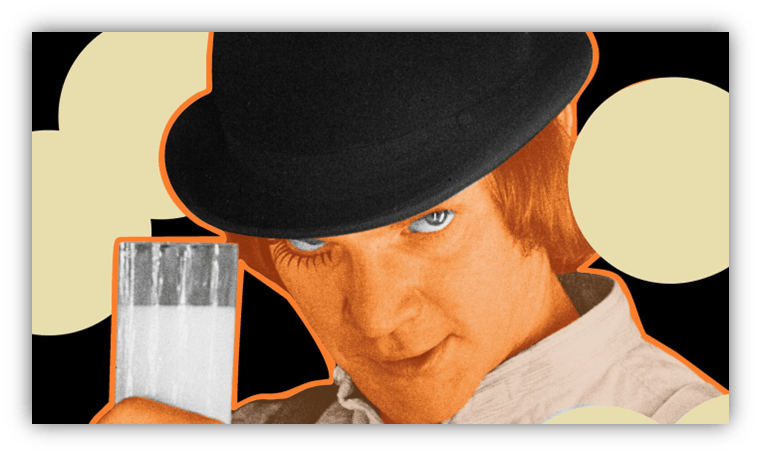

1971 was the year that Stanley Kubrick’s film A Clockwork Orange opened in theaters.

Based on Anthony Burgess’s 1962 novel, the film is set in a near future in which streets are overrun by gangs.

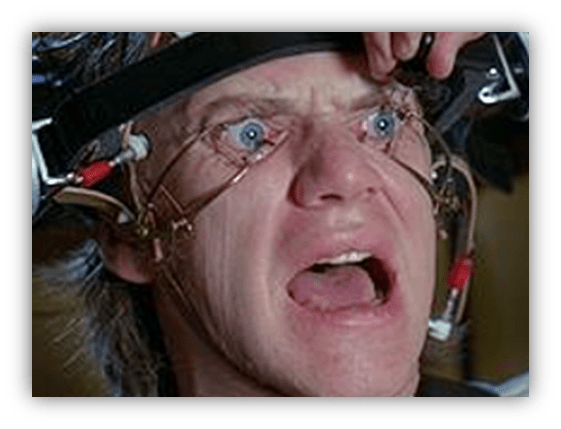

Alex is a brutal young gang leader and a male of simple pleasures: drugs, fights, theft, rape, and the music of Ludwig van Beethoven.

Once arrested, Alex is subjected to a radical new behavioral treatment based on psychological conditioning. Rendered helpless whenever he tries to initiate violence, Alex soon finds the world taking its revenge upon him.

Burgess’s novel is mostly in line with other 20th century dystopian tales. Its real critique is on the treatment that society imposes on Alex in order to control him. For Burgess, free will is an essential component of a moral society—and someone being conditioned against their will to follow the law is as outlandish and unnatural as the titular clockwork orange.

Importantly, Burgess doesn’t just conclude his story with Alex regaining his sense of control, he also has Alex start to grow out of his vicious habits. Not due to any treatment imposed but simply due to growth and maturity over time.

Given the author’s intent for the story, it is quite striking that Kubrick’s film cuts out that more promising conclusion. Instead, the film’s final scenes focus on the capriciousness of societal rules.

On a dime, Alex switches from villain to hero in society’s eyes due to the whims of the powers that be…in this case the politicians using Alex and others for their own selfish interests.

The film ends with Alex free to go, his depraved fantasies returning to him, the monster reawakened.

Instead of thinking about free will, responsibility, and growth like Anthony Burgess had intended for his story, movie audiences were instead thinking something like “lol, nothing matters.” It’s a devastatingly barbed satire, with a takeaway that’s far more cynical than Burgess ever intended.

Not surprisingly, Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange became a cult hit.

More than anything else, the film was praised for its aesthetic innovations—its strange costumes and sets, a futuristic dialect mixing Russian and Cockney slang, and its haunting electronic scores from Wendy Carlos.

To Burgess’ likely horror, young fans of the film actually admired the Alex character. And those who looked beyond the aesthetics for a message could easily conclude that right and wrong were nothing but conveniences of the ruling powers.

Taste the Rainbow!

While most dystopian novels are set in a distant or not-to-distant future, it’s not a necessary condition.

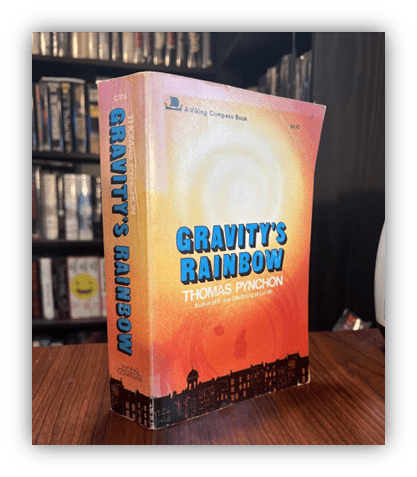

Thomas Pynchon’s 1973 Gravity’s Rainbow is set in England, 1944-1945, in the midst of German missile strikes on London.

Tyrone Slothrop is an American working with the English to collect information about German missile designs. Yet he is being watched and followed constantly, for reasons he doesn’t understand.

It turns out that the geospatial layout of the Nazi missile attacks are somehow linked to locations where Slothrop had been sexually active. The sites of mass death and destruction seem to be set by this young man’s own…missile launches.

Yeah, I imagine you weren’t expecting that narrative turn.

The tone of Gravity’s Rainbow easily shifts from living nightmare to slapstick satire, and back again. Like in Samuel Beckett’s surreal theater pieces, the humor gives Pynchon’s story its heart. Far from nullifying the horror of the war content, it makes it feel more real. After all, humor is the only sane way to cope with a life of dreadful absurdity. And arguably the only way to defy it.

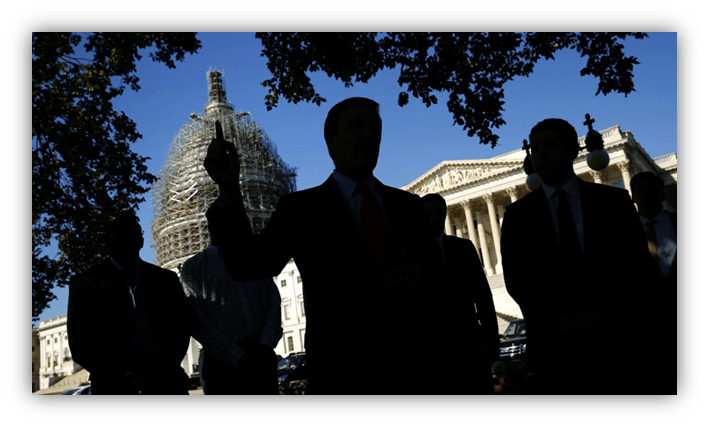

But Pynchon’s humor is also one borne of deep cynicism and paranoia. The central villain of the story is not Hitler or the Nazi Party.

It’s not the parties who surveil Slothrop, or even the psychologists who control his behavior. Instead, it’s the forces behind all that; those at the top and in the shadows. And it’s a power that transcends the factions of war.

Sound kooky? Maybe so. But consider this bit of true historical trivia:

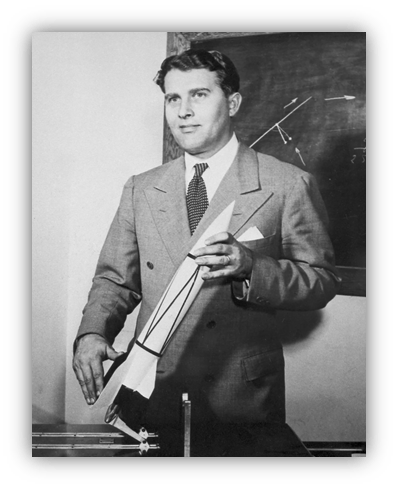

In 1969, the United States successfully sent a spaceship to the moon. The rocket technology that launched Apollo 11 into outer space was in fact based on the work of Werner Van Braun, a former Nazi SS officer.

This was the very same man who had designed the dreaded V-2 missiles that ravaged the Allied nations of Europe during World War 2. The most potent symbol of American world leadership was made possible by the murderous tech of a pardoned war criminal. Go…team?

Consider also that Shell Oil supplied fuel to power the weapons of both sides of the war. Coca-Cola made Fanta as a product to sell to the Nazis. No matter who won, a fortune was made. Before the war, after the war, the machine rolls on and on.

The true villain of Gravity’s Rainbow is the system that profits from all sides. It is the nameless “they.” And They will always get their due.

Meanwhile, everyone else is left hoping to hear the scream of a V-2 missile. Because if you hear it, that means you were out of its target range. You live to see another day. And then you carry on doing whatever it is you were doing. Until next time.

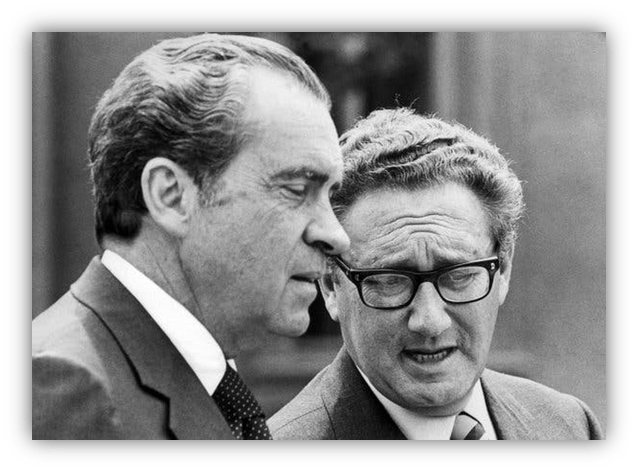

Despite being set in Europe several decades in the past, Gravity’s Rainbow also conjured the feeling of life in Nixon’s and Kissinger’s America, at the height of the Cold War. And all the absurdity and uncertainty that came with it.

For all its crazy freeform narrative style, it’s why the book ended up being quite popular upon release. Its targeting was dead-on.

We Are the Crash!

In 1968, the author J.G. Ballard published a short work titled “Why I Want to F*ck Ronald Reagan.”

This wasn’t an essay, and it wasn’t a short story either. Instead, it was a fictional scientific report centered on subjects’ reactions to clips of Governor Reagan speaking. In dry and technical prose, the “report” details bizarre, disturbing scenes, such as:

“Subjects were required to construct the optimum auto disaster victim by placing a replica of Reagan’s head on the unretouched photographs of crash fatalities. In 82% of cases, massive rear-end collisions were selected with a preference for expressed fecal matter and rectal hemorrhages. Further tests were conducted to define the optimum model-year.”

Ballard had been reeling from the death of his wife from pneumonia, and he had turned to his writing to process his grief.

But he also found himself watching an American governor and presidential candidate Reagan introduce a new type of politics to the world. And he wanted to make sense of that phenomenon as well. Ballard explained:

“In his commercials, Reagan used the smooth, teleprompter-perfect tones of the TV auto-salesman to project a political message that was absolutely the reverse of bland and reassuring. A complete discontinuity existed between Reagan’s manner and body language, on the one hand, and his scarily simplistic right-wing message on the other.“

“Above all, it struck me that Reagan was the first politician to exploit the fact that his TV audience would not be listening too closely, if at all, to what he was saying, and indeed might well assume, from his manner and presentation, that he was saying the exact opposite of the words actually emerging from his mouth.”

Ballard’s piece was resolutely postmodern in nature, but it was done to highlight the postmodern style that Reagan himself brought to the world.

The psychosexual and sadistic elements in the piece help to bring out the latent darkness that such an approach to politics could mask. But it’s also Ballard working out his own trauma, and his own bewilderment with the world around him. With his haunting and bizarre imagery, Ballard conjured a present-day dystopian dream world that almost felt like science fiction, but not quite.

Ballard wrote more experimental pieces in this vein, and in 1970 the works were compiled in a book called The Atrocity Exhibition.

For added surreal effect, the illustrated version features twisted sendups of medical textbook images. Among other stories, the book contained “Crash,” a short piece that expanded on the erotic fixation with auto collisions that first featured in his Reagan piece. This premise was itself expanded into a proper novel in 1973, also titled Crash.

Crash‘s premise of people deriving sexual pleasure from breaking their bodies in car crashes is…disturbing, to say the least. What was this man thinking? Was this some sort of sick pornography?

In the introductory essay for Crash, Ballard says: yes, it basically is. But he also perfectly crystallizes the cultural moment that would necessitate such grotesque paraphilia:

“The marriage of reason and nightmare that has dominated the 20th century has given birth to an ever more ambiguous world.

“Across the communications landscape move the spectres of sinister technologies and the dreams that money can buy. Thermo-nuclear weapons systems and soft-drink commercials coexist in an overlit realm ruled by advertising and pseudo-events, science, and pornography. Over our lives preside the great twin leitmotifs of the 20th century – sex and paranoia.”

“Needless to say, the ultimate role of Crash is cautionary, a warning against that brutal, erotic and overlit realm that beckons more and more persuasively to us from the margins of the technological landscape.”

This description feels like the perfect layout for Gravity’s Rainbow as well as Crash. And it’s not too far from Kubrick’s take on A Clockwork Orange either.

These stories are all, in their ways, satirical cautionary tales.

The authors all exaggerate their characters’ compulsions, reducing humans to malfunctioning flesh bots – clockwork oranges, all. But they do so primarily to highlight how we machines are tuned and tweaked by higher powers, for larger interests. Not just manipulative psychologists, advertisers, or spies, but the distal authorities they serve.

Yet, being thoroughly postmodern critiques, they also have a grim laugh at the sad state of it all. Not to mention indulge in some of the very things they say they’re critiquing: most notably pop-art commercialism. It’s very much a situation of having your cake and eating it too.

Despite and because of their conflicted attacks, these stories perfectly conjured the anxiety, the paranoia, and the cynicism of the era. They were well received by jaded young adults, and in time they came to shape the culture as well as reflect it.

It’s hard to imagine what certain music scenes of the 1970s would look like without their influence.

Glam rock, punk, synth pop, industrial, maybe more.

Then there’s the graphic novels of Alan Moore, the horror films of David Cronenberg, and plenty of contemporary visual artists.

These dystopian works helped a generation learn to start worrying, and start to love the bomb.

They were almost pro-actively dystopian in that sense.

The new generation was savvy enough to know we’d never be watched over by machines of loving grace.

But they’d be lying if they said they didn’t admire the cold, shimmering chrome of their inhuman captors.

After all, with enough polish or gloss, gray can be beautiful too…

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Like watching fiction crossing over into real life, a one-woman performance that slyly referenced The Handmaid’s Tale that was broadcasted on live television earlier this year. It was brilliant. The viewer had to be familiar with Margaret Atwood to get it. And conversely, those familiar with Atwood’s work may have felt a little horror. The woman reading the scripted dramatic piece, I suspect, didn’t know the source material she was naively conveying.

My favorite contemporary dystopian science fiction novels are those that predict the future of woman.

We need a future based on the SCUM Manifesto.

Quite a piece to read at 6 a.m.! 🙂 Seriously, Phylum, I appreciate the way your work forces me to think and engage, even at an hour when I’m not fully able to do so…

I will admit that, while shelves of Swamp Thing, Watchmen and the like can attest to my appreciation of Alan Moore and company, dystopian fiction has never fully caught on with me. I simply recognize my vulnerability when it comes to psychologically dark themes (and realities). I don’t live in a shiny, happy world, but I do force myself to move away from horror of all sorts when I feel it’s cutting a little too close to my core. I guess the challenge is to not get so bubble-wrapped that I fail to see the suffering of the world (or the life within it). That’s where fictional works of any kind can be most effective — in piercing that bubble-wrap.

Haha, thanks!

I find that dystopian fiction to be strangely more comforting in these troubled times. Gravity’s Rainbow makes a whole lot more sense now…

So that’s where the Joy Division and Danny Brown titles came from.

I was not familiar at all with J.G. Ballard before, besides him writing the source material to Empire of the Sun. Thanks for introducing me to his work.

Crash also informed the premise of the song “Warm Leatherette,” most famously covered by Grace Jones.

Freshman year of college, my roommate and I went a saw a showing of A Clockwork Orange at the student center. I had never seen an R-rated movie before and my roommate likely hadn’t either. This one was rated X. I could not believe what I was watching. When it was over, we were both kind of quiet and then my roommate said, “I feel like s***. I concurred. I got the basic message of “trying to control people is bad” but I felt wrong about watching women get raped and all of the other over-the-top violence. I didn’t know the book was very different from the movie, and I think I would have gotten more out of that. Yes, we could have walked out and not watched the whole thing, but I’ve only walked out of one movie in the theater in my life- Rhinestone, and that just had to be done.

Yeah, that scene is disturbing even today.

A Clockwork Orange was withdrawn from viewing in the UK by Kubrick himself in 1973. It couldn’t be shown in cinemas, on TV and wasn’t available on VHS or DVD until after his death.

This was due to those young fans you mention who saw Alex as a something to be admired. And imitated. There were a number of court cases from the time which cited the film’s influence on the defendant. A parallel that was drawn by both the prosecution and the defence. Some of it sounds like opportunism on the part of the legal teams.

The one case where the film did seem central was a rape where the perpetrators sang Singing In The Rain. Whether they would have offended regardless and the film just added an extra distasteful element to the act or they were actually incited by the film to action is another matter.

Ther are also reports of youths adopting the fashion or Alex and his droogs and intimidating those around them. How widespread that was and whether it was all part of convincing the populace of the need for moral panic is open to conjecture.

As far as I can tell Kubrick didn’t give a clear explanation of his reasons for withdrawing the film but did say that he didn’t see that it could have that kind of violent influence.

Life imitating art or art imitating life?

I didn’t know about the different endings. Due to the ban on the film I read the book many years before I finally got to see it and didn’t pick up on the change. I prefer Burgess’ take but fear Kubrick’s could be more accurate.

There’s probably some truth to both the prosecution and defense. In such a busy and fragmented culture, so many things could be a provocation to violence, but that’s not to say that it didn’t play some role. If not “Singing in the Rain,” then “Helter Skelter” or some other signifier.

I am inclined to agree with your take on the two stories…unfortunately.