It’s a call and response between a teacher and his students:

“I,” the war veteran barks.

“Kill,” the pupils rejoin.

Cobra Kai is not a dojo for the faint of heart.

John Kreese (Martin Kove) instills in his followers a mindset that is anathema to Mr. Miyagi (Pat Morita): Karate as a weapon. It’s metaphor, but does the militant sensei’s disciples know that?

Somebody saved Daniel LaRusso (Ralph Macchio) last night. It was the maintenance man at the apartment complex where he lives with his mother (Randee Heller), New Jersey transplants, both, finding their way in the land of blonde.

Miyagi enters the lair to speak with the former army man after his subordinates nearly kill Daniel in a five-against-one fight over Ally (Elizabeth Shue), the ex-girlfriend of the teacher’s protégé, Johnny Lawrence (William Zabka).

In exchange for granting Daniel immunity from future beatings, Miyagi proposes that they settle matters at the California state karate tournament, where Daniel and Johnny can fight for points, not their lives.

In retrospect, Cobra Kai looks less like a dojo than fight club.

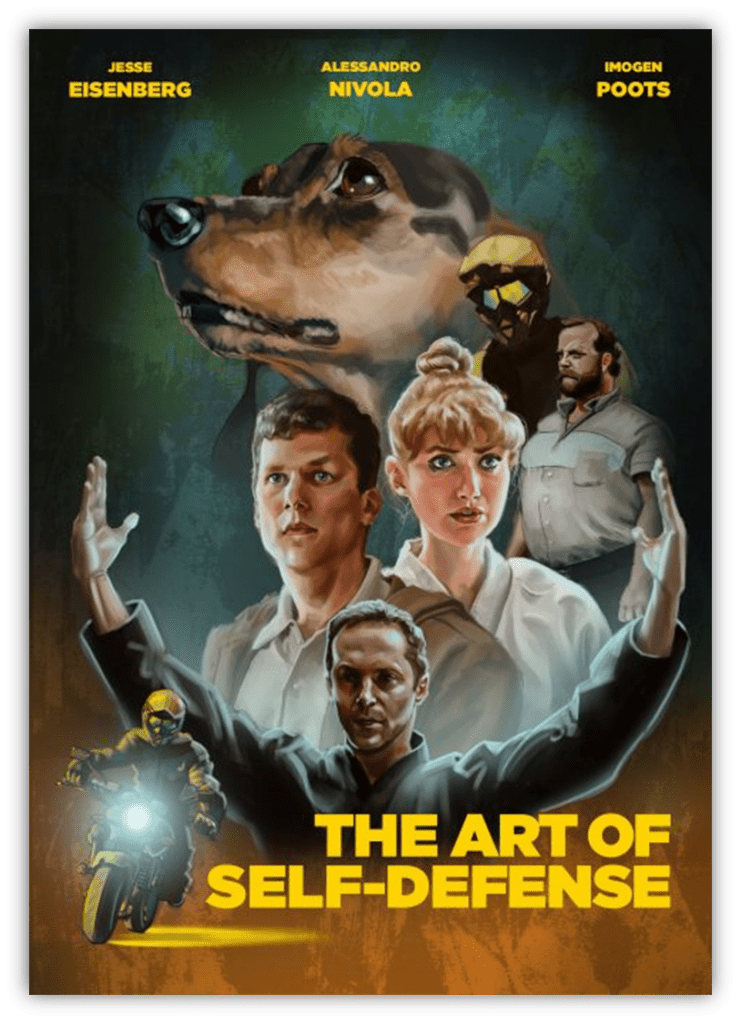

The Art Of Self-Defense, directed by Riley Stearns, recalls both John G. Avildsen’s The Karate Kid, and more prominently, the novel Fight Club by Chuck Palahniuk.

David Fincher adapted Palahniuk’s work into, perhaps, a film every bit as prophetic as the much-talked about Margaret Atwood novel and subsequent web series, The Handmaid’s Tale, starring Elisabeth Moss.

The Art Of Self-Defense forces the viewer to look at The Karate Kid with new eyes. Miyagi-do, the defensive-oriented discipline Miyagi learned from his Okinawan ancestors. That which he imparts to Daniel may be deemed not masculine enough by a modern audience. That’s the point Stearns is making.

John Kreese and his minions used to be villains. But after the co-opting of the Cobra Kai emblem in recent years, now they are viewed by some as anti-heroes.

Daniel doesn’t have sole custody to the Joe Esposito song, You’re the Best, anymore.

It’s late. It’s dark. Casey (Jesse Eisenberg) is tired, but the accountant has a dog to feed. The grocery store is close by, so the car stays home. Casey walks. He gets stopped by a motorcyclist. “Do you have a gun?” the driver asks. Casey doesn’t have a gun.

On his return trip, the filmmaker recreates Daniel’s encounter with Cobra Kai. What was his fate, had Mr. Miyagi not been there to intervene? The dead sprint starts in earnest. Casey loves his dachshund. He heroically carries the bag of dog food for a while before dropping it. Casey ends up in an ICU after his body is stomped upon by the enquiring rider and his buddies.

Recuperating at home, Casey decides to buy a handgun. Disappointedly, he leaves the store empty-handed, having first to pass a background check and abide by the requisite seven-day waiting period.

Casey acquired this idea from a men’s magazine belonging to a co-worker that he secretly Xeroxed at work.

Imagine Details on steroids. The magazine is posited as an instruction manual on how to be an alpha male.

In The Karate Kid, Daniel doesn’t buy a copy of “Guns And Ammo” at the neighborhood 7-11. To defend himself, Daniel learns karate from diagrams in a book. But Casey is living in “1984”, too. The Art of Self-Defense is a period piece with no pop culture references or product placement to signify time and place. It’s the technology, relics from the last century such as push-button phones, VCRs, and copy machines that orientates the audience.

It’s the nineties, a decade in italics, a theater lab of sorts, a dystopian world in scale.

Casey is looking for a Mr. Miyagi of his own. He finds him at the dojo next to the gun store, a sensei who calls himself Sensei (Alessandro Nivola).

“Karate is a language,” according to Sensei; he translates English into kinetic motion, using the martial art as subtitles for his evening plans, which includes grocery shopping and a movie rental. He punctuates the monologue with a battle cry you’d make after ripping an opponent’s heart out from his chest. Going to Blockbuster turns into a rite of passage.

He makes the gender-neutral act of grocery shopping sound masculine.

This raging megalomaniac adapts the karate belt system into a black/white binary for men in regard to their lifestyle choices, with no accounting for the in-between colors on the spectrum. Sensei categorizes everything from your first name to your musical preferences as being either feminine or masculine. Adult contemporary is feminine. Metal is masculine.

Like a screenwriting ninja, Stearns introduces the undeniable influence of Fight Club, a yin to The Karate Kid’s yang, in the record store scene without anybody none being the wiser. The CD section is loaded with soft rock titles whereas metal has been whittled down to a single jewel case. Instead of bare-knuckle boxing, “a generation of men raised by women” are taking karate lessons, men who “don’t wanna die without any scars.”

Casey’s first exposure to metal (Full of Hell’s “Burst Synapse”) turns him into “Jack’s medulla oblangata.”The family parked next to him roll up their windows.

Similar to The Narrator (Edward Norton) in Fight Club, Casey’s pent-up self-loathing spawns an alter-ego, a Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt) in slacks. Colleagues at work look differently at Casey, whose asexual persona gets subsumed by an alpha male disguise, just like how Marla (Helena Bonham Carter) and the feral pugilists know that The Narrator and Tyler are one and the same.

A montage of this self-assured version of Casey follows, ending with the metal neophyte cold-cocking his boss in the neck. Sensei is not the Mr. Miyagi figure Casey needs. This transformation from wimp to thug puts the karate student in a heightened state of disproportion.

Conversely, a tenet of Miyagi-do, the discipline imparted to Daniel, addresses the importance of equilibrium. “Lesson not just karate only. Lesson for whole life. Whole life have a balance, everything better.”

Yeah, it’s corny. At some point, you half-expect Miyagi to say “Use the Force, Daniel-san.”

In Fight Club, The Narrator, an insomniac, plays tourist at encounter groups, a parasite among the dying. It’s a safe place where he can cry. His mental stability is undone by the presence of another interloper; a hale woman, albeit a chain-smoker. Marla Singer (Helena Bonham Carter) is the catalyst for The Narrator’s later-ego, Tyler Durden, a Nietzsche-like “over-man”. Tyler doesn’t hug other dudes. Even the man with “b*tch t***”, whose name turns out to be Robert Paulsen (Meat Loaf), a testicular cancer survivor, eventually gets sick of himself and joins The Narrator on his journey.

An office drone, like the automobile industry recall specialist, a galvanized Casey stands over Grant (Hauke Bahr), his gasping boss, and with a hectoring voice, proclaims: “Stop trying to be my friend. Bosses cannot be friends. It doesn’t work that way.” Casey doesn’t know what to do with this newfound flux of testosterone. At home, he looks at the world outside his window illuminated by moonlight where the curtains part.

It’s time to utilize the black stripe, an honor not usually bestowed to a yellow belt, but Sensei makes an exception, this after hours invitation to the dojo, when Casey recounted his near-death experience with muggers. “I wanna be what intimidates me.” The black stripe grants Casey permission to be an insurgent. Karate changes Casey when he delivers a kick that knocks out the tooth of a higher-ranking student, a purple belt, who looks up at him with a bloody smile.

Night class is where the hallucinatory nihilism of Chuck Palahniuk’s world eats zen alive. The mentor/protege dynamic remains intact, but it starts to resemble the one between The Narrator and Tyler Durden more than Mr. Miyagi and Daniel LaRusso. Night class is a cult. Sensei runs the dojo but he’s an acolyte to the real leader “Grand Master” (revered for killing men with a deadly index finger to the forehead), just like his students, who bow to a hanged picture of this god-like figure after every session. Violence becomes a social norm.

On his first night, he watches Anna (Imogen Poots), still sore over being passed over for promotion, pulverize Thomas (Steve Teresa), a newly-anointed black belt, to near-death. It will remind the viewer of The Narrator, who explains: “I felt like destroying something beautiful,” as he stares down at Angel Face (Jared Leto) after turning his face into raw meat. The mascaraed goth is a female surrogate.

It’s coded misogyny. “Any hint of femininity threatens masculine identity,” writes Brenda Ayers, author of Neo-Victorian Madness: Re-Diagnosing 19th Century Mental Illness In Literature, which “must be exorcised through violence”.

Quite pointedly, there are no women in Cobra Kai, either. Miyagi-do is a reactive strategy of fighting deemed not virile enough for the two-time armed forces karate champion. In John’s estimation, Daniel LaRusso fights like a girl. That’s why at the tournament, Sensei gives Bobby (Ron Thomas) the directive to “put him out of commission” and for Johnny to “sweep the leg.”

Anna fights like a grrl. She earns the right to be The Next Karate Kid.

The next entry to the series, directed by Christopher Cain, starred Hillary Swank as Julie Pierce, the target of harassment by the Alpha Elite, a school security fraternity. It’s no wonder Kimberly Pierce cast her as Brandon Teena in Boys Don’t Cry. Neither Julie nor the film itself seems to fully grasp what a group of angry young men can do to her.

Mr. Miyagi prepares Julie for a confrontation against her enemies… “and” the prom.

Anna, on the other hand, doesn’t enjoy being a girl. It takes Casey to draw out her long-dormant feminine side. Anna turns out to be the Miyagi-figure that Casey was looking for. When Casey breaks into the inter sanctum of the karate facility, a padlocked room with an incinerator and video equipment, he learns that Anna stopped Thomas from delivering the finishing touch on his life.

The maternal side Anna consigned to Sensei for erasure, resurfaces after years of deprogramming. She associates compassion with femininity, as does Sensei, who tells Casey: “I realize now that her being a woman will prevent her from ever becoming a man.” Bludgeoning Thomas restores her performative mojo.

In the girl’s locker room, while Thomas recovers, Anna explains to Casey how she finally earned her own changing area. The potential for sexual violence that The Next Karate Kid whitewashes, The Art of Self-Defense tackles, as it depicts a patriarchal culture without limits that can turn toxic when left unchecked.

Anna escapes rape with her superior karate. Sensei claims Anna led her on. And yet she stays to endure further subjugation in this hierarchal terrordome. On some level, Anna loves the man she hates; the man whose approval means everything to her.

In miniature, the filmmaker depicts both, a cult of personality and Stockholm syndrome, which goes together like peas and carrots. The Art of Self-Defense is technically a period piece, but the Brechtian distanciation the filmmaker employs has an unmooring effect on time and place. The bar is called “Bar”. The dog food is called “Dog Food”. The dojo is called “Karate”. Instead of melodrama, the filmmaker operates under a framework of absurdism to underscore the film’s improbable milieu.

It’s more Mike Judge than Douglas Sirk.

The Art of Self-Defense is Dogville, directed by Lars Von Trier, with the chalk outlines filled in with David Byrne-like architecture circa 1978.

Adam Gordon, the father of two young daughters, in Ben Lerner’s Pulitzer Prize-nominated novel The Topeka School, tries in vain to reason with another father, whose son won’t yield the playground slide to “stupid, ugly girls.” Adam, a congenial and rational man, who sees fatherhood as a fraternity, wants this stranger to help him make “the playground a safe space for” Luna and Amaya. But the man brushes the former high school debate champion off. Adam believes that there is “nothing to be gained by confrontation,” but maybe he’s wrong.

Unlike The Art of Self-Defense, Lerner sets The Topeka School in the present-day. The playground bully will grow up to be Sensei, not The Narrator in Fight Club, or John Kreese in The Karate Kid, both of who come across as pacifists compared to this sociopath. Neither Tyler Durden nor Johnny Lawrence killed people. Sensei’s disciple, Casey, on the other hand, beats a cop to death and shoots his master in the forehead. Sure, The Art of Self-Defense is over-the-top. It has to be. Riley Stevens doesn’t want people to misconstrue anarchy as a social tool of righteousness.

The Topeka School is a bildungsroman. The incident at the playground is a scene from real life. Lerner wondered how his daughters would “internalize whatever life lesson,” was to be gained by the fraught incident. Maybe Luna will grow up to be Anna. In an ever-increasing patriarchal world, she will have to be both, not the “other”. As Anna puts it, rewriting Mr. Miyagi:

“Up until this point, you’ve been taught violence equals strength and compassion equals weakness. This ideology is limiting. It is possible to be brutally tolerant or peacefully savage.”

Let the author know that you liked their post with a “heart” upvote!

My option to ‘like’ disappeared on me, mt!

[Sends ticket to Goodboy at the help desk….]

Cappie, I so enjoy going on your review journey’s! What’s your criteria for which movies to share with us?

Hello, Ms.g8r,

We are in receipt of your ticket #867-5309. We think that we know what the problem is; it has to do with the way the caching works for the page.

A quick workaround on desktop is to refresh the page, either via an F5, or a right click/reload action. On mobile, a simple refresh should work.

I hope that I was helpful. You will receive a survey soon via e-mail, if you would consider responding, thank you.

I strive for “Five Milk-Bones.”

Love,

Goodboy

Movies that I have memorized. Movies that I have memorized that other people would know. And then there is the challenge of not turning my beliefs into a lecture. Writing in the third-person helps a lot.

I am used to writing in the anonymity of the IMDb. This is a new experience for me. I am always aware of the fact that this time, there may be people who might actually read what I write. It can be terrifying.

Thank you, dutchg8r.

Great write-up, Cappie. You mix together these disparate narrative elements into a tasty thematic salad.

Could I get my testosterone on the side?