One of the biggest selling records of 1923 – a Number One, if Joel Whitburn’s calculations are to be believed – was “Love Sends A Little Gift Of Roses” by the Carl Fenton Orchestra.

A dreamy little foxtrot, rather similar to all the other dreamy little foxtrots that were out at the time.

Whilst the Carl Fenton Orchestra was virtually indistinguishable from all the other Jazz Dance Orchestras of the era, in at least one way they were very, very different:

Because the Carl Fenton Orchestra… didn’t exist!

Maybe that’s a bit of an exaggeration. Clearly, somebody was playing on the records. But it wasn’t Carl Fenton.

And we can feel certain that it wasn’t Carl Fenton, because there was no Carl Fenton. Carl Fenton did not exist. Brunswick Records had simply made Carl Fenton up!

Now, why did Brunswick Records do that? And who were Brunswick Records?

Based in the small country town of Dubuque in Iowa: it’s unlikely that Brunswick Records ever had big plans to compete against Victor and Columbia, the two absolute giants of the first few decades of the recording industry.

They even initially used Edison’s Vertical Cut technology, a format that was fast going out of style. Also, they weren’t even a proper phonograph company.

They were a furniture company.

They built pianos.

And billiard tables.

And phonograph-players. Which is why they decided they needed to make the records that would be played on them.

Somehow, largely due to the surprising number of Jazz Dance Orchestras floating around the mid-West, they briefly became one of the biggest record companies in America! And like any big phonograph company of the era, they needed their own house band.

Every record company had a house band, whose job it was to churn out instrumental versions of the latest Tin Pan Alley/Broadway/vaudeville hits.

Victor had the Victor Military Band, and what a terribly generic and unimaginative name that was! They also had the Victor Light Opera Company. They really didn’t put a lot of thought into their band names.

Columbia did a bit better. Columbia had Charles A. Prince. The “A” stood for Adams.

Charles was related to, and named after, both “Adams” Presidents.

If a song was killing it on Broadway – “going over” in the parlance of the times – or if it was getting some buzz in the sheet music shops, it wouldn’t be long before Victor and Columbia each brought out their own instrumental versions. “Love Sends A Little Gift Of Roses,” for example, would also be a hit for The Columba Orchestra, and there were at least another five hit versions floating around.

Each record company needed their own versions of the latest hit songs because they were mostly sold through their own chain of phonograph stores, who also sold the phonograph machines to play them on.

This is why you’ll hear such bizarre facts as…

- The first recording of the first blues song – W.C. Handy’s “Memphis Blues”– being recorded by the very white and not very bluesy Victor Military Band.

This is the sort of random historical fact that happens when your job is to record virtually every song hitting the sheet-music stands. Personally, I prefer the Charles A. Prince version, recorded a week or so later.

Charles was going through a weird phase at the time, in which he was adding random spaced-out pin whistles, bird and animal noises to all his records. It was only a short phase, but we did end up getting this, the second recorded version of a blues song.

Weirdly enough, when W.C. Handy did finally get around to recording his own version of “Memphis Blues” in 1923, it would sound remarkably like a marching band – and nothing like what you are probably imagining the blues of 1923 to sound like.

(What did the blues of 1923 sound like? Find out when I cover it in December!)

By the early 20s, Victor had realized that just naming your house band after your company wasn’t enough anymore and hired Paul Whiteman to take its place.

Much of the huge success of Paul Whiteman in the early 20s – as covered in my first article– wasn’t so much because he was personally popular, but because his records – like the Victor Military Band before him – were covers of already huge Broadway and Tin Pan Alley hits.

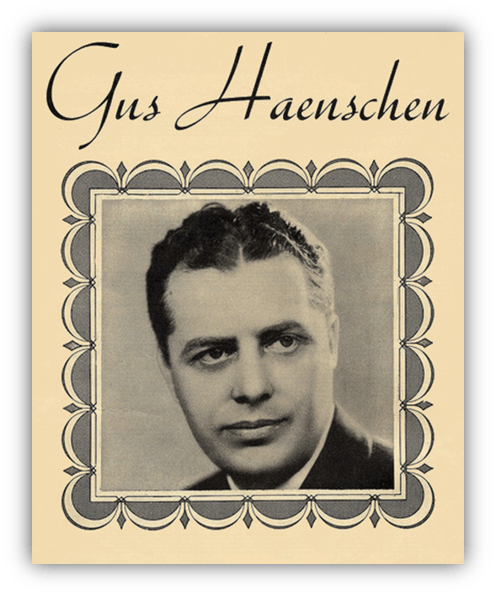

So Brunswick decided: that they needed their own Paul Whiteman. They had hired a music director named Walter Gustave Haenschen. By rights, it should have been his name on the records.

But he – or someone at Brunswick – realized that ‘Walter Gustave Haenschen’ was a terrible name to put on a record. It wasn’t so much that it wasn’t catchy (although it wasn’t,) – it was that it was so German! *

The early 20s were not a good time to be German in America.

* You know who else was German?

Milli Vanilli !

Is your mind blown yet?

America had just finished fighting a war with Germany, and anti-German sentiment was still high. Tin Pan Alley had done everything it could to encourage patriotic Americans to hate the Kaiser, and – particularly once someone figured out that “Hun” rhymes with “gun,” thereby lending itself to countless “I’ll chase the little Hun, with my little gun” lyrical puns – enflame hatred of Germans in general.

Rarely – perhaps never – had a war inspired so many pro-war pop songs. Pop song titles of the era included:

- “We’ll Yank The Kaiser’s Moustache Down”

- “I’d Kill The Kaiser For You” (how sweet!),

- “If I Only Had My Razor Under The Kaiser’s Chin”

- and “When We’ve Taken The Kaiser’s Scalp”

Not all of these were hits exactly, but their mere existence proves that there was a market for this stuff.

Pro-war pop was so popular that even something with the unpromising title of “Just like Washington Crossed The Delaware (General Pershing Will Cross The Rhine)” did become a big hit!

In an environment like that: Walter Gustave Haenschen didn’t stand a chance.

So he created a fake name instead:

Carl Fenton’s Orchestra. (Walter did get his name on the label as an arranger though, so he wasn’t totally left out)

“How did they come up with the fake name? “ I hear you ask?

The ‘Fenton’ bit, was the name of a small town in Missouri, near St. Louis, from which Walter came.

The name ‘Carl’ seems to have been chosen from a poll of Brunswick’s office workers.

Since there was no actual Carl Fenton, it didn’t really matter who played on the record. Usually, Walter was involved. But sometimes it was completely different bands. Red Nichols – quite a major name in 1920s jazz circles – had a record put out as ‘Carl Fenton.’

As record sales piled up, so did requests for the Carl Fenton Orchestra to perform. Even then, it was not Walter who led the band.

It was Ruby Greenberg.

Now Ruby was the face of the Carl Fenton Orchestra.

This, as best as I can tell, is his face:

Meanwhile, Walter was getting a whole lot of work on radio. Here I feel I should make a quip about him having the perfect face for radio, and suggest his ugliness to be another reason why Ruby got the job as the public face of Carl Fenton…

But: the handful of photos I’ve been able to find suggest that he scrubbed up quite well.

No. Radio was fast becoming where the action was.

So much so that record sales plummeted in the mid-20s, since folk could now listen to music on the radio for free –

– and Walter was simply too busy working on the music for The Palmolive Hour, and and other such shows.

He seemed to be doing okay.

So Walter left Brunswick and Ruby bought the rights to the Carl Fenton Orchestra.

But this wasn’t enough for Ruby.

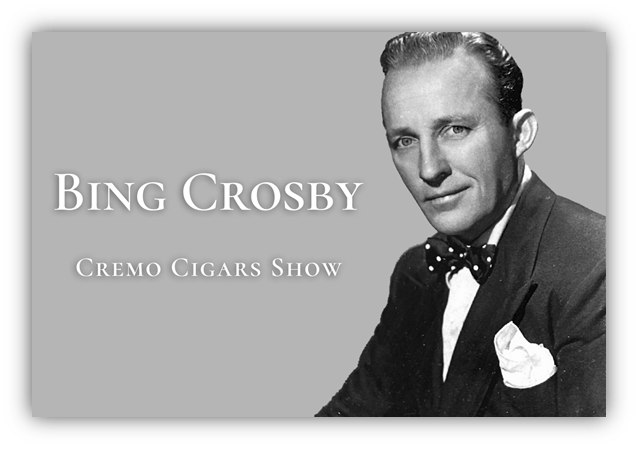

In the early 30s – by which time the Carl Fenton Orchestra was the backing orchestra for a radio show with Bing Crosby – Ruby, sick of people mistakenly calling him Carl, finally took the plunge:

And officially changed his name to Carl Fenton!

Finally, the Carl Fenton Orchestra was being led by an actual Carl Fenton!

But… by a cruel twist of fate, Bing Crosby’s radio show was sponsored by Cremo Cigars, and so the orchestra was typically referred to as “The Cremo Orchestra.”

The show only lasted for a year or so, which must have been a relief for poor Ruby…

I mean, Carl…

Otherwise he may have had to change his name again…

To Cremo!! Oh the humanity!!!

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Oops… I seem to have posted Charles Prince’s “St Louis Blues” – containing no bird or animal noises – instead of “Memphis Blues” with bird and animal noises.

Here’s “Memphis Blues” with bird and animal noises.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1tMK4y6QBY8

I never heard this version before. So weird. It beats the recording eccentricities of Moondog by almost 40 years.

The early recordings of Handy’s work are often a bit too vanilli for my tastes, though Handy himself made one that sounded like early jazz:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gpp75gQ-T6Y

But of course, no one served it up nearly as compelling as Bessie Smith, who made it her own:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Bo3f_9hLkQ

Very interesting stuff! We’re creating a Venn diagram bubble bath of 1920s music here on tnocs!

[It’s a delight to see the confluence of music, art, history, and “random collaboration” that we’ve experienced of late.]

[Shoehorning in a huge thanks here, to all!]

And it’s all so interesting. Good stuff, Dan!

When I think “Military Style”, I of course picture birds, goats, and cartoon people slipping on banana peels. This is awesomely bizarre.

Spike Jones must have been taking notes.

This is good stuff. So Carl Fenton was more of a ‘concept’, but then sort of became the real thing. I didn’t know this about ‘him’. Learning the ins and outs of the early recording industry is fascinating stuff!

Carl Fenton’s biopic should be directed by Alan Smithee.

Beat me to it! Great minds…

That’s so funny!

So for a period of time, Carl Fenton was like Alan Smithee?

Great story. Further evidence that there’s nothing new under the sun. Reading up on Gus and it appears he also composed under the pseudonym of Paul Crane. A man of many identities.