It’s easy to overlook the quiet heroes of war:

The people behind the scenes who never fired a shot.

The WRENs of WATU were among them.

They out-smarted the enemy, rewrote the rulebook, and helped win one of the longest, hardest battles of World War II.

And they did it armed with nothing more than intellect, data, and chalk.

By 1941, Britain was in real trouble.

WWII was only two years old but the country depended on imports for 70% of its food and 95% of its fuel.

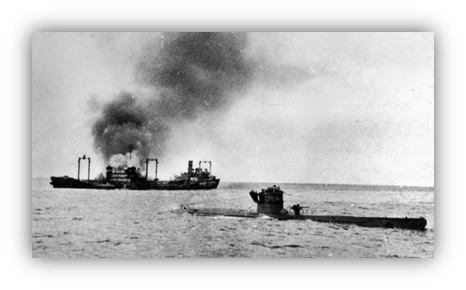

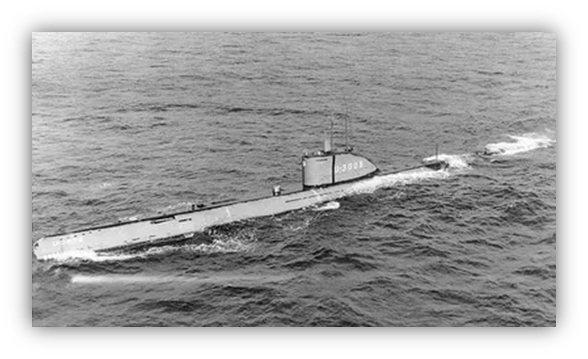

German submarines were sinking merchant ships faster than they could be replaced.

It was called the Battle of the Atlantic.

If Britain ran out of food, they’d have no choice but to surrender.

Churchill knew it.

Hitler knew it.

The British took to grouping merchant vessels together in a convoy and protecting them with warships. That didn’t help, and no one knew why. All that was known was the German U-boats attacked at night, and submerged before the British warships could respond. Something had to be done.

Captain Gilbert Roberts was a Royal Navy officer placed on shore duty while he recovered from tuberculosis.

In January 1942, when he was back on his feet, he was assigned the task of setting up a small group to analyze the U-boat attacks.

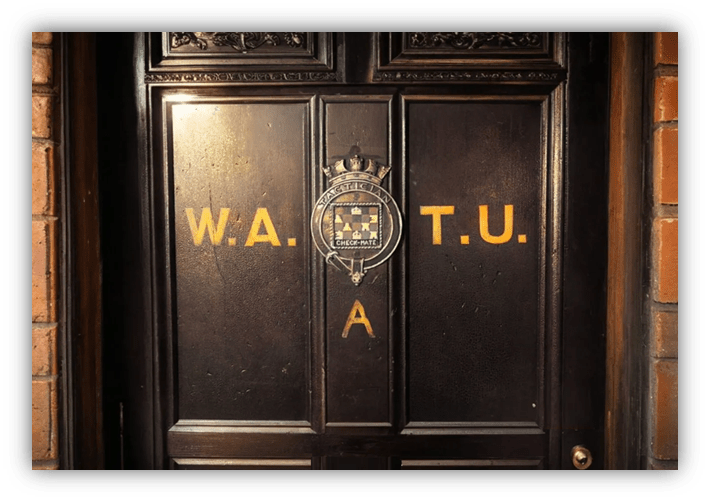

He called it the Western Approaches Tactical Unit (WATU). Its home was a set of rooms in Liverpool.

Before he left London, he was sent into a meeting. There, Churchill himself told him, “Find out what is happening, and sink the U-boats.”

The group he led wasn’t made up of experienced sailors or officers. Those men were off fighting the war.

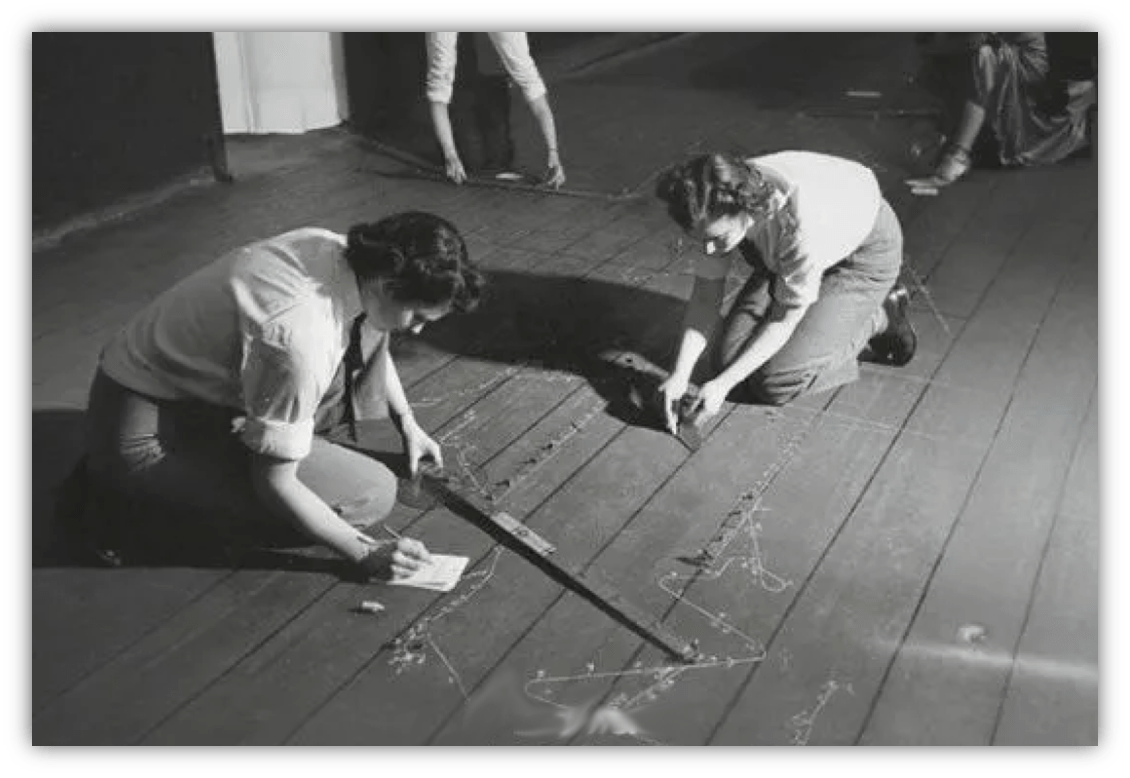

Instead, he had been given a staff of mathematicians, linguists, and statisticians from the Women’s Royal Naval Service, or WRENS. Like the boys who had been shipped to battlefields, some of these women were girls just out of school.

Some were still teenagers.

They learned fast, mastering anti-submarine tools and terminology. Some already spoke German, as did Roberts, and were able to translate U-boat manuals. More importantly, they interviewed survivors of the U-boat attacks:

And were able to plot the events using chalk and wooden ship models on the floor.

Roberts and his team reconstructed the attacks on the game board, and tried to see patterns.

They were surprised to find that some U-boats were not attacking from outside the convoy as the Royal Navy’s escort commanders assumed — because that’s what the Germans did in the First World War. Instead, the submarines were sneaking into the middle of the convoys at night on the surface — so they could use their fast diesel engines and look like other convoy ships on radar — and firing at close range from inside the formation.

Those attacks in the dark from within the convoy explained why there were such heavy losses.

The wargames, sketched on the linoleum floor with chalk, made that invisible tactic visible.

The other finding was that the escort ships adhered to rigid command procedures.

If a sonar operator detected a possible U-boat, the escort’s captain couldn’t act immediately. Instead, the contact had to be confirmed, reported up the chain of command, and approved before any attack was made. This bureaucratic delay could take minutes — long enough for a U-boat to fire its torpedoes and submerge. WATU’s wargames repeatedly showed how deadly this delay was.

It wasn’t the first time that British military protocol got in the way of success.

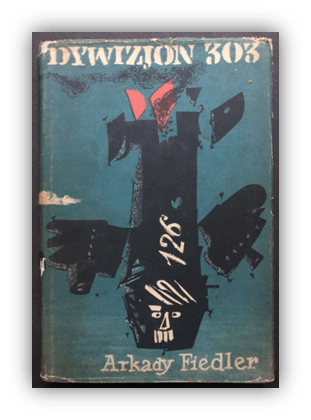

When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Polish fighter pilots took to the air in obsolete aircraft against impossible odds.

Many escaped through France and fought again during the brief campaign there in 1940. After France fell, they fled to Britain.

The Royal Air Force didn’t quite know what to do with them.

The Poles spoke little English, had fierce tempers, and flew with a style the British considered reckless. At first, the RAF wanted them to retrain from scratch.

The pilots objected. They had combat experience, they didn’t want or need lectures. Finally, after some bureaucratic wrangling, Squadron 303 was formed in July 1940.

The British system relied heavily on formation flying — the “Vic” formation, a tight triangle of three planes.

It looked neat, but it wasn’t practical in combat.

It forced pilots to focus more on keeping position than spotting enemies, and it made the whole group an easy target. The Poles thought it was nonsense.

Squadron 303 flew in looser, more fluid groupings, allowing each pilot to maneuver freely and attack as opportunity arose.

They hunted down German planes without waiting for permission from headquarters.

The RAF worried they were undisciplined, but they couldn’t argue with the results.

In just six weeks of combat during the Battle of Britain, Squadron 303 shot down 126 enemy aircraft, more than any other unit in the RAF, and with fewer losses than most. When British officers asked how they achieved such results, the Poles said they fought to win, not to follow rules.

When WATU discovered that protocol was delaying response time, they used their wargames to develop a new one.

A 21-year-old WREN, statistical analyst Jean Laidlaw, named the operation “Raspberry,” as in blowing a raspberry at Hitler. It worked like this:

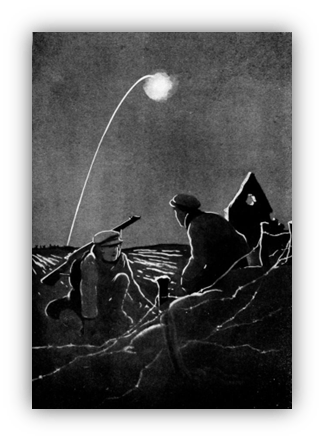

When a merchant ship in the convoy was hit or a close torpedo wake was sighted, anyone of any rank could immediately start the procedure — there was no need to wait for an order from the top. The escort would launch two white rockets and announce the code word “raspberry” over the radio.

The lead escorts would fire star shells to light up the area. One escort would sweep directly down the convoy’s stern looking for a surfaced sub.

Escorts on the rear and flanks converged on the convoy, and would then turn outwards and do long outward sweeps away from the convoy, firing star shells and using sonar/radar to search the surface for a U-boat for about ten minutes. Then they turned and swept back to their starting positions — effectively combing the entire perimeter and blocking easy escape routes.

The combined converging-then-sweeping movement forced a surfaced U-boat either to stay surfaced and be attacked, or to dive, losing the speed advantage and facing depth charges.

Unlike the earlier single-direction sweep tactic, Raspberry had all escorts participate, removing delay and blind spots.

Raspberry was tested repeatedly on the WATU game floor, but the naval brass didn’t want to accept the idea.

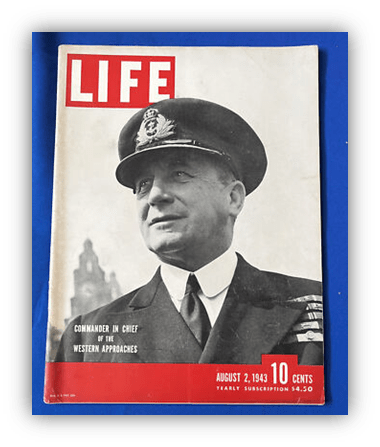

Admiral Sir Max Horton, a hero submariner, was commander-in-chief of the Western Approaches.

He believed that wargames were just games and could never replace his years of experience.

Horton visited WATU, even though he thought it was a waste of time, and was challenged to play ‘The Game,’ as they had nicknamed it. He would play the U-boat commander fighting against someone standing behind a canvas screen with only a few holes cut in it. The screen limited what his opponent could see, just as the convoys were blinded by night.

Five games were played.

Horton lost all five of his U-boats.

He accused Roberts of rigging The Game and was infuriated when his opponent stepped from behind the canvas.

It was Janet Okell, a tactical analyst and wargaming specialist.

She was 20 and had never been on a boat.

Horton had been beaten by a girl. He put WATU’s recommendations into effect.

Through the summer of 1942, U-boats had been hitting as many as 146 ships a month.

Once WATU trained convoy personnel on their new tactics in early 1943, things changed quickly. By May, the number of ships hit had dropped to 49, and by June 1943 it was 27.

In that same May, the Germans lost 43 U-boats, their worst losses of the war.

It became known as “Black May.”

German Admiral Karl Dönitz recognized the defeat and ordered his submarines to withdraw from the North Atlantic entirely. They gave up.

The turnaround took less than a year. It began on the WATU game floor, where WRENS with chalk and model ships rewrote the rules. Squadron 303 rewrote their rules, too.

However, the people who do the work rarely get the credit.

The accolades go to the commanders who had to be convinced that girls and rogues were on to something. Some of the WRENS’ work remained classified until recently.

But their names:

Janet Okell, Jean Laidlaw, Laura Janet Howes, June Duncan, Elizabeth Drake, and 61 others:

— deserve to stand beside those of the admirals and captains they once trained.

The book Dywizjon 303 (Polish for “Squadron 303”) by Arkady Fiedler fictionalized the pilots’ names for their security.

They too deserve recognition.

ADDENDUM: If you want more detail, get A Game Of Birds And Wolves by Simon Parkin.

https://bookshop.org/p/books/a-game-of-birds-and-wolves-the-ingenious-young-women-whose-secret-board-game-helped-win-world-war-ii-simon-parkin/432b0023848972f9?ean=9780316492065&next=t

Thanks for this piece, Bill. I learned a lot from it about a part of history I didn’t know. Hope your weekend is a good one.

Excellent stuff Bill. I knew bits of this but not the full story.

If anyone visits Liverpool and is all Beatled out (was there a few months ago and even as a Beatles fan, the fab four nostalgia industry has really gone into overdrive in the last 20 years) there are also plenty of excellent non Beatles related attractions. Including the Western Approaches Museum in the secret bunker WATU used during the war. I haven’t been (yet) but my dad was there last year and found it fascinating.

The role that the WRENS played chimes with the work done at the more well known Bletchley Park. Where they were engaged in code breaking and unravelled the mysteries of the Enigma machine. A large number of ordinary people played their parts in that all kinds of different ways. Another fascinating visit – that one I have been to.

Liverpool is definitely on my list of places to go, and I apologize in advance if I support a few of the Beatles tourist traps. If there’s a pretty nurse selling poppies from a tray on Penny Lane, I’m buying one.

I need to look into Bletchley Park as well.

No need to apologise, if you go to Liverpool you definitely have to do some of the Beatles related attractions, especially as a music fan. Its just that there is now an overload. I was at uni in Warrington in the mid 90s, half an hour from Liverpool so we’d go quite often. At that time there was The Beatles Story (still going strong), a version of The Cavern and not much else. From what I understand in the 70s and 80s not much was made of the city being their origin at all. The further we get from them the more the nostalgia (and the money making opportunities!) grows.

Bletchley Park is great, even the teen who isn’t so keen on museums anymore found it engaging. They had some mock up enigma machines on which to follow instructions to see how it worked. We cracked the code but none of us could fathom how. One of those things where you can only admire those who worked it out. Even more so when you learn that before they figured out the machine they were code breaking using pencil and paper and their minds.

I loved the first couple of seasons of The Bletchley Circle. If you’re unfamiliar, it’s a mystery series about a group of women who had worked at Bletchley. They are trying to solve a series of murders using the skills they used in the war. But they have difficulty convincing anyone in authority to take them seriously because their work in the war was classified, and they can’t explain how they developed their skills. It’s a really interesting take on how those women who did such important work in the war adapted to post-war life in more mundane jobs.

Okay. This is the fourth time I’ve read your comment, wanting to reply but I felt the post was too silly for the subject matter I’m supposed to be addressing. So I watched the trailer. I found episode one on DailyMotion. I like the lighting. The first five seconds reminded me of the machine in Enigma, starring a young Kate Winslet. It looks like Enigma, but instead of one woman, you have a whole team of women.

But that’s not what I originally meant to write. Are you cleverly referencing Bertolt Brecht, or is the common word in both films just a coincidence?

Not silly at all. Bletchley Park was the name of the estate that housed the Government Code and Cypher School. Alan Turing was based there, as well as thousands of other code-breakers, the majority of whom were women. The show that I referenced is an imagining of what life was like for those women after the war when they had to switch from doing vitally important work that used their talents and helped the allied forces achieve victory to the life that was expected of them in post-war England, i.e. being housewives, working as secretaries or cleaners, etc. Because their work was still classified, they only had each other to process all of this with.

I found it to be a fascinating premise, and I enjoyed the first season especially.

I’m no WWII expert, but the history is fascinating. Thanks for this lesson!

My son has always said that after people retire, they start watching WWII documentaries. It’s a joke but I just retired and here we are.

I love this article, V-dog.

You’re telling us something about the past to comment on the present.

As per usual, I deleted several posts before settling on this one.

Exactly! Almost all history comments on now, if only we’re smart enough to listen.

A fantastic and inspirational blog, Bill. Just the type that we need today. World War II is filled with hundreds of these stories of little-known triumphs that made a big effort in helping the Allies win the war, and it’s about damn time the people behind these victories get their honors as a result.