1. They Walked In Line

In March of 1945, the Sociology department at Columbia University hosted a lecture series entitled “The Aftermath of National Socialism: Cultural Aspects of the Collapse of National Socialism.”

Germany would not surrender for several more months at this point, but their eventual defeat by the Allied Nations seemed to be within reach. The purpose of the lecture series was to allow the greatest scholars of sociology to provide ideas for a possible way forward.

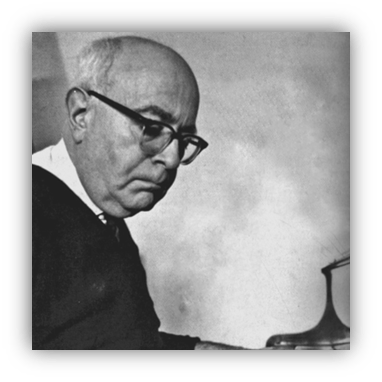

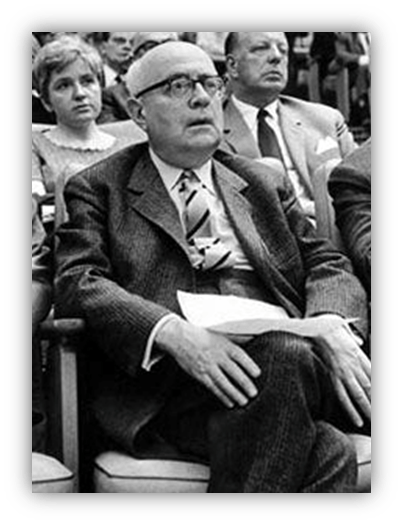

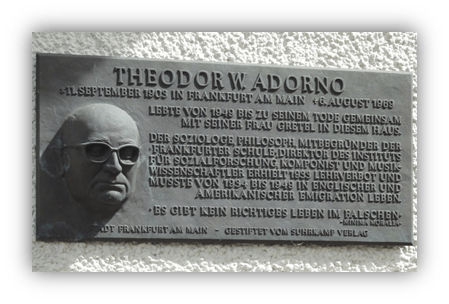

One of the invited speakers was Theodor Adorno.

As a German refugee who had fled from the to the United States to escape his death by the Nazis, Adorno had firsthand experience with the anti-culture of Adolf Hitler and his goose stepping thugs.

In a few years he would publish his research on the authoritarian personality, now considered seminal for the field.

Moreover, he had spent the last four years in the American academic communities of Princeton, NJ and Berkeley, CA. So who better to draw on such stark contrasts of experience in order to help liberal democratic nations restore the soul of his blighted motherland?

Alas, Adorno gave his colleagues a taste of something rather different. He presented a paper called “What National Socialism Has Done to the Arts.”

Though the principal focus of the paper was on music, Adorno laid out a case for how Nazism was actually the culmination of a broader trend of cultural deterioration that had transformed Germany. One that began in the 20th century.

And one that he observed in Western liberal democracies everywhere. Especially the United States.

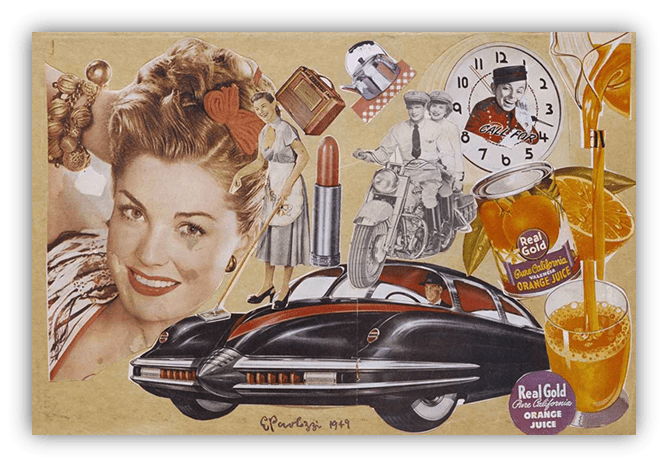

Despite how Americans saw themselves, their country wasn’t some bastion of freedom. It was a deeply sick society, with a populace growing ever weaker and more complacent by the overpowering fumes of the culture industry.

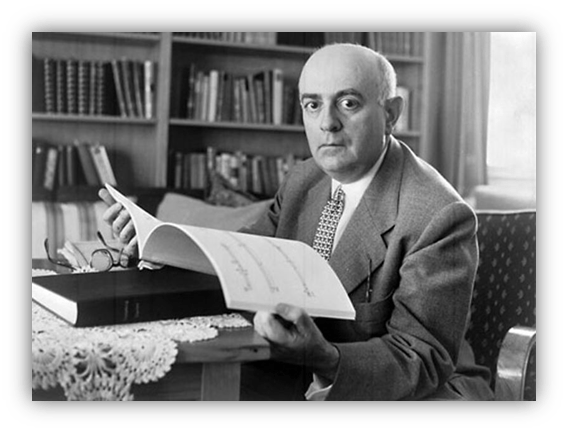

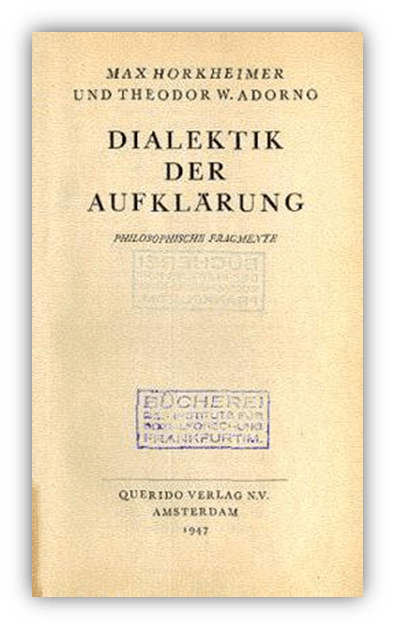

Adorno would expound on this basic premise in a collaborative work with his mentor and colleague, Max Horkheimer. Published in 1947, Dialectic of Enlightenment was a brutal, relentless critique of Western Enlightenment and the ever-present byproduct of its late-stage incarnation: mass consumerism.

The authors don’t fault the populace for the changes that occurred, but they note with pitiless detail all of the ways in which mass consumerism has made us all complacent, self-gratifying zombies.

“There is nothing left for the consumer to classify.”

“Producers have done it for him…Not only are the hit songs, stars, and soap operas cyclically recurrent and rigidly invariable types, but the specific content of the entertainment itself is derived from them and only appears to change.”

“The details are interchangeable.“

“…As soon as the film begins, it is quite clear how it will end, and who will be rewarded, punished, or forgotten.”

“In light music, once the trained ear has heard the first notes of the hit song, it can guess what is coming and feel flattered when it does come.”

Horkheimer & Adorno, 1947

Maybe this sounds to you like the ranting of a grumpy elitist. But Horkheimer and Adorno argue that this problem is deeply serious: because mass consumerism serves to hollow out a culture.

All focus and energy is on one’s work, one’s consumption, and one’s relaxation habits in order to do more work.

There is no time or incentive to meaningfully contribute to one’s community, to think independently, or to fully feel one’s humanity.

One of the major reasons for this is that art has been reduced to a mere product.

“Instead of being a decisive means to express fundamentals about human existence and human society, art has assumed the function of a realm of consumer goods among others,

Measured only according to what people “can get out of it,” the amount of gratification or pleasure it provides them with or, to a certain extent, its historical or educational value.”

Adorno, 1945

Under such conditions, easy comforts and pleasurable distractions are the priority. Maybe a few strategic shocks for excitement.

Yet a culture built on mass consumption is no culture at all. It’s an endless wave of transactions centered on countless commodities.

And, the authors argue, it is in such a spiritual and cultural vacuum that fascism can take root.

[Liberal democracy got you down? Set it alight with something dangerously delicious. Introducing the Nuremberger with Cheese. Two luscious patties of beef, flame-broiled like a book in a bonfire, topped with a sesame bun made from 100% immigrant-free wheat. Now that’s something to rally around.]

How then can we prepare ourselves against the threat of fascism?

How to cultivate thoughtfulness? Independence? How to feel our humanity in the fullest while living in a society that’s dominated by the culture industry?

This sounds like a job for the avant garde! Right?

Not so fast.

2. A Means to An End

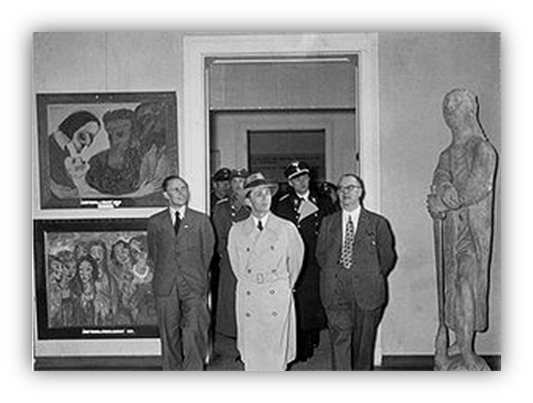

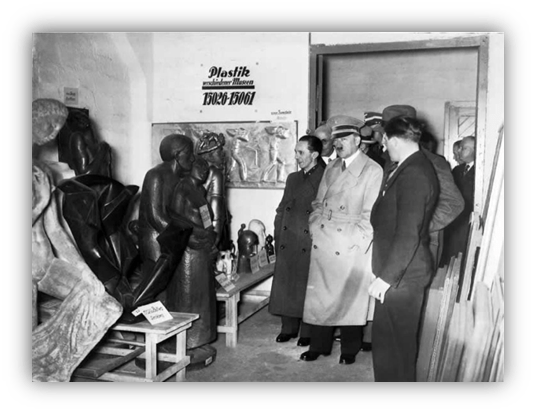

On July 19, 1937, two state-sponsored art exhibitions in Munich were opened to the public.

One was the so-called “Great German Art Exhibition,” which featured sculptures and paintings hand-picked by Adolf Hitler to represent German culture under the Third Reich.

These works were all done in the classical style of Western fine arts, showing off the artists’ technical skill, and showcasing conventional standards of beauty.

It was also typical Nazi propaganda.

The other show was much more controversial, by design. This one was advertised as an exhibition of “degenerate” art.

It was a showing of all the modern works that had recently been banned by the Nazis. Those who visited the exhibit were subjected to a heavily curated tour of shock and outrageousness.

The artworks exhibited there showed off the many unconventional styles that had gripped the art world for the previous 50 years or so.

Most were not shocking on their own, per se. But they were arranged and assembled throughout the building in order to create confusion, frustration, decadence, incoherence, and sensory overload among the visiting public.

Paintings were haphazardly placed together in makeshift mural assemblages. The walls were defaced with graffiti that insulted the works and their makers. Some sculptures were actually positioned to impede passage, so attendees had to scrape against a statue in order to get through a room.

And the public loved it. To be sure, they hated what they saw there, but how they loved to hate it. They loved the thrill of their outrage. They loved the moral clarity that flowed from their hate.

Modern artists had been at best media curiosities for most German folks; and most were too obscure to be known. Here was perhaps the first example of urban bohemian weirdness being pushed into the national spotlight, and fashioned into a target of populist contempt. It wouldn’t be the last.

Yet this exhibition was itself a sort of conceptual art. Its design showed avant garde principles at work.

Like the Dadaists, it reappropriated existing cultural artifacts for new and irreverent ends, and yet it doubled down on the power of the pieces to shock and offend. This was avant garde used against itself.

Admittedly, the Nazi’s use of orchestrated chaos here was a unique case within their typical propaganda M.O. But autocrats of more recent history would also come to employ modern art principles for the sake of controlling crowds, confusing and cowing them into complacency.

Notably, one person who had seen the potential fascist dimensions in avant garde art all along was Theodor Adorno.

Adorno made a distinction between modernist art and avant garde art.

While the former merely tried to create a sound or vision for the modern world, the latter was combative. It was committed to maximalism and a desire to shock. The spirit of this tendency was totalitarian, Adorno argued. It did not invite conversation or independent thought; it shouted over everything around it.

This series has noted how several avant garde artists had flirted with authoritarian sentiments. One of them even co-wrote Mussolini’s Fascist Manifesto!

Most of the others had leftist sympathies, but often of the radical revolutionary type. Were these revolutionaries fighting for society’s freedom, or to impose their own wills? Adorno tended to assume the latter.

Whether art is thrillingly combative, pleasantly distracting, or infectiously catchy, the end result is the same: it crowds out critical thinking. And it further fragments our culture into a collection of personal preferences.

How then to foster a more serious and responsible sense of freedom in our society?

3. From Safety to Where?

Adorno was not what you would call an optimist, but he did have a notion of what kind of artists might nourish our ailing souls as we navigate the churning tides of modernity.

“An artist who still deserves the name should proclaim nothing, not even humanism.”

“He should not yield to any pressure of the ever more overwhelming social organizations of our time but should express, in full command of meaning and potentialities of today’s processes of rationalization, that human existence led under its command is not a human one.“

“The human survives today only where it is ready to challenge, by its very appearance and its determined irreconcilability, the dictate of the present man-made but merciless world.”

Theodor Adorno, 1945

The trick for Adorno is someone who can work against all of the habits and comforts that keep people complacent—without resorting to combative musical tyranny. So in terms of music, what might that be?

Adorno himself studied composition with the modernist Alban Berg.

While his opinion on the 12-tone serialist approach of Berg, Webern, and Shönberg shifted back and forth over time, he was generally respectful of these musicians.

To my knowledge he never wrote about the work of Olivier Messiaen or Edgar Varese—or even Ruth Crawford Seeger, who also studied with Berg—but my guess is that he would appreciate their brand of modernism as well.

So, a question arises: must we all become devotees of a composer that I have unkindly described as “Wagner with the randomizer settings maxed out,” in order to save our society? Or perhaps learn to love a man that I previously said made “sculptures of sound” rather than music?

I will humbly suggest: no. But also…kind of!

Adorno’s genius lies in his diagnosis of the larger cultural system. In terms of the history and the dynamics and broad sociology, he’s devastatingly dead on.

When he gets to particulars, however, he can be a real purist. Not just a snob (and he does have his moments!), but someone who doesn’t permit or acknowledge compromises of his ideal.

One such compromise that I think deserves mention is the appreciation of pop art. In my opinion, jazz was one the first examples of pop art, setting a fuzzy boundary between modern art and commercial entertainment.

Yes, it’s got a relentless rhythm and often sports infectious melodies, but it also introduces dissonance, unconventional tonality, and a constant need to shake up whatever’s come before. Artists like Billie Holiday also injected their songs with real pain and sorrow. Adorno famously hated jazz, but so what?

Maybe it’s “best” for all of us to listen to train our ears on artists like Shönberg and Varese, who proclaim nothing beyond their inventive musical grammar. But wouldn’t it be more realistic to at least start with something more palatable?

Like a Gershwin or a Benny Goodman?

Adorno talks of this stuff in terms of achieved ideal or failed ideal, but what about the notion of movement toward a goal? Of stepping stones? Or exercise?

I can accept that we’re all a lot more mentally and spiritually flabby than we’re supposed to be, given the omnipresent distractions that plague our culture. But a realistic exercise routine starts small, and proceeds gradually, does it not?

I will never be against pure dumb fun for its own sake. But I do think that we should mix up our consumption to include works that are at least a little bit challenging.

Maybe that means art rap.

Or jazz fusion.

Or a thoughtful indie film.

Or maybe it means a modernist concerto full of violin shrieks.

Whatever it might be, I tend to think that it’s the process of engagement and growth that matters most. Beyond that, who cares if a work in question is tricked out or…un-Adorned?

4. Transmission

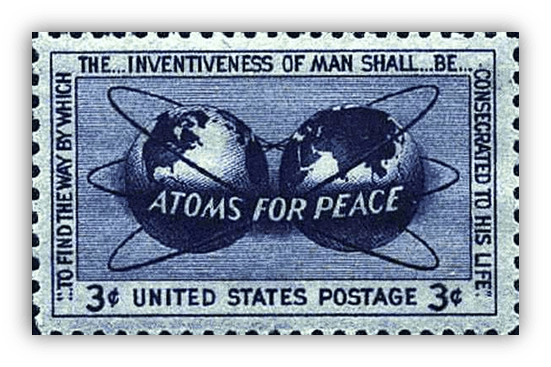

Once the Second Great War was won and the Axis of Evil had been toppled, Soviet Russia revealed itself as the new threat to global democratic order.

We had entered into the Atomic Age, a time of wonder, of terror, and of possibility.

In the wake of our newly supercharged enemy of democracy, American and Western European governments became increasingly invested in paying lip service to the notion of intellectual freedom and international cultural exchange.

A major ripple in this cultural push for liberty and against tyranny was a growing encouragement across nations of increased knowledge, free exchange of ideas, cross-cultural appreciation, and a newfound openness to artistic expression.

The modernist and avant garde worlds would benefit greatly from this postwar push for cultural openness. Naturally, these particular musicians, painters, sculptors, and writers would take the notion of freedom into new, strange, and sometimes challenging territories.

Yet freedom can take us to all sorts of places if we’re not careful.

How would the artists use their freedom? Would it be used to start conversations and cultivate free thinking? Or would it cultivate apathy, decadence, cynicism, or cultural disconnection?

In a future series, I’ll take a look at some artistic works from subsequent decades, and try to answer those questions. Whether it’s modernist, avant garde, or some pop hybrid, it’s all fair game.

Hopefully I’ll turn you onto some art that you hadn’t known, or maybe dismissed before. At the very least, I hope these articles entertain as well as stimulate thought.

Because in this late-stage culture industry environment, we gotta embrace the pop as well as the art, amirite?

Hope you’ve enjoyed the series, and I’ll be back for some sister installments at some point!

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Noting my own slowness, and not your incompetence, I have no idea what your overall goal of your dude where’s my van series has been. I read most of them, but admit that a couple tougher articles were presented on days that I just didn’t have the energy to invest in something more than kitty cat videos. It seemed like a series of discussions of philosophical topics, but was there an overall arc? Were the topics related and progressing towards a goal, or was the series just semi-unrelated topics? Again, I am asking because I often fail to see the forest for the trees and have to have things spelled out a little more explicitly.

Todays article was interesting. I enjoyed reading it. Sometimes these kinds of rants by people only seem to be lengthly justifications for why exactly what their taste in art/music/culture is, is what is best for society at large. The kind of thing I would write, just with bigger words.

I just want to know if Theodor ate refrigerated apples or not. If he didn’t eat them at room temperature, I’m not sure I have the time of day for his other whimsies.

Thanks Link. I didn’t have a solid arc in mind, more a broad set of interests and themes. “Modern art and avant garde as a window into the modern world,” or something like that.

Some were short and to the point, while others were a little more experimental in form, or tried for more “writerly” prose. Just, whatever I felt seemed right at the time.

And yeah, some entries were lighter and some were heavier than others. Read what you wish, whenever it makes sense for you.

Adorno can be a difficult person to bring up, because he can be an insufferable snob, but that’s not why I’m interested in him.

I can’t speak to the apples but…if I had to lean one way, I would wager he sank his teeth into the chilled flesh of all fruit he consumed.

But what if I told you that we humans need to learn to eat refrigerated apples…in order to save humanity?

Then I’d know you were off your rocker. 🙂

Ohhhh, cat videos.

I know, right?

I forget where I read this but I heard the best way to gauge someone is by asking who their favorite Beatle is. I like that because it’s succinct, smart, and probably correct. The refrigerated apples question rises to that level.

When my brother found me re-reading Adorno not too long ago, he gave me a copy of Hannah Arendt’s essays in Between Past and Future to check out. Arendt was also a German philosopher who fled the Nazis for her Jewish heritage, and she also wrote on culture in the modern age.

In her essay, The Crisis in Culture. Arendt points out many of the same problems that Adorno does regarding a mass consumerist society hollowing out a culture.

Still, all told, she’s not as unrelentingly bleak as Adorno can be.

One area that perhaps sheds a ray of hope is her argument for rejuvenating “taste” as a community standard. Arendt argues that taste is not the same as personal preference, and confusing the two leads to the societal relativism that pervades modern life.

Today we often uphold the adage that “you can’t argue taste,” but Arendt invites us to have those conversations, in the interest of feeling out shared ideals and priorities, and articulating what pieces resonate with us, and why they are or should be a lasting culture artifact.

Now, I personally think that there is something very special about the “you can’t argue taste” value of consumerism…something that has even helped to facilitate social progress.

For instance, while W.E.B. Dubois dreamed of black art that could function as effective propaganda to win the hearts and minds of white Americans to the idea of black humanity–what ultimately proved to be a crucial outlet for such cultural reprogramming turned out to be the very music he snubbed as lowly, degrading entertainment: jazz music. Jazz in the1920s was thought to pander to white audiences, and in some respects it did, but it also allowed black musicians to project black dignity, wow white spectators with impressive musical accomplishment, and warm people’s hearts with a new music that stirred them to dance. Those white audiences were simply following their impulses for easy pleasure, but in doing so they were ultimately transformed.

Similarly, Ronald Reagan’s neo-liberal transformation of America ironically paved the way for a more tolerant and diverse country, as market demands for compelling entertainers like Prince and Chuck D helped young audiences tune into styles and ideas that earlier generations never would have considered.

All of that is to say that, while I do think Arendt is right to argue for the rejuvenation of taste for the sake of shared cultural standards, it’s a tricky thing to actually accomplish. For one, it has to be a conversation rather than a shout-down, as any attempt to argue for taste needs to coexist with our need for liberal pluralism. And ideally it should also respect the role that self-interested consumerism can sometimes play in social transformation.

But still, without dismissing personal preference, and without being elitist, it’s reasonable to make arguments for the cultural value of certain pieces that move us. We often do this to some small extent when we write about books and movies and games and such. Perhaps all Arendt’s essay has done for me is highlight how it’s not just reasonable to think about such arguments, but potentially important.

Even if we can’t change the larger cultural of society, we have the power to set standards locally. To highlight what it is we value and why. And maybe to contribute to an understanding of art and culture that endures for longer than the next release cycle.

As for Adorno’s own music, I thoroughly dig this string quartet piece:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v5Tc4mXodrI

I wish Susan Sontag was still alive. We need more public intellectuals.

Sending twenty-one red roses to Friend Phylum for a wonderful and insightful look at art, music, history, and the lessons that we can learn – if we choose to do so.

Well done, and thank you for your time, talent, and engagement.

🌹🌹🌹🌹🌹🌹🌹🌹🌹🌹🌹🌹

Hey, you’re nine red roses short there, buddy!

Sorry. It’s only December 7, and we’re already tapped out for the month. Gary and Goodboy have blown up the budget for the tnocs Christmas party.

So what would Adorno think of Joy Division? Would he appreciate the Atmosphere they create or be disappointed that the new dawn fades into the more palatable sound of music that New Order purvey?

I don’t think of them as challenging but I know plenty that do. I suppose they aren’t really a band that you turn to for a good time.

It’s been an epic trail. Look forward to seeing what comes next.

I can’t say for sure about Joy Division. He did enjoy some flirtations with pop culture, most notably Brecht and Weill’s works like the Threepenny Opera.

But…to be safe, I’ll say there likely would be no love lost between them.

Did you know that Werner Herzog got zero votes in the latest Sight and Sound poll? Fitzcarraldo and Aguirre, Wrath of God both fell out of favor with the gatekeepers of cinema. I don’t know why. I took it personally, somehow.

Danish filmmaker Hylnur Palmason seems to like Herzog fine enough. Godland was my favorite purchase from the recent Criterion Collection 50% off sale. It’s thoughtful.

Modernist cinema can be hit or miss. I think the slow-cinema movement is modernist. Apichatpong Weersethakul puts me to sleep. I ask myself this all the time: What is ambitious? What is pretentious? Hou Hsiao Hsien requires a lot of patience, but is it worth it? Sometimes. Criterion picked the right film.

Bela Tarr is ambitious.

I hope Tarr comes out of retirement. But he’ll probably have to make a film outside his native land.

Yorgos Lanthimos is my favorite contemporary avant garde filmmaker. His films are playful, therefore accessible.

I’m down for the occasional cat/dog video binge, though.

Werner Herzog’s epics are almost late-Romantic in style, like Gustav Mahler’s symphonies. I can see why people these days might dismiss them as grim, self-serious overindulgence, rather than thoughtfully expressive narratives. People don’t like raw angst these days; it needs to be cut with distance and sarcasm.

At least Werner is aware of people’s perception of him, as evidence by this now-classic scene from Rick & Morty:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rw1cdRew-Zg

Postmodernism always wins in the end.