Estonia is a small country.

Bigger than Maryland.

But smaller than West Virginia.

Its location on the Baltic Sea is its greatest strength:

Because its ports support global trade.

But also its historically greatest weakness – because other powers wanted those ports.

Like Poland and the other two Baltic states, it has no mountain ranges to keep invaders out. All were variously taken over by Russia, Prussia, and Sweden.

For most of the first millennium, the area that’s now Estonia was home to independent Finno-Ugric tribes living in small communities. They had their own language and traditions, and were skilled sailors and traders.

Their independence was ended in the early 1200s by the Northern Crusades.

German crusaders, joined by Danish and later Swedish forces, invaded and Christianized the region.

By the mid-13th century, nearly all of what is now Estonia had been conquered and absorbed into medieval Christian Europe.

Estonian peasants became serfs working the land to serve their German-speaking landlords.

That elite class, known as the Baltic Germans, would continue to dominate politics and culture for centuries, even under later occupiers.

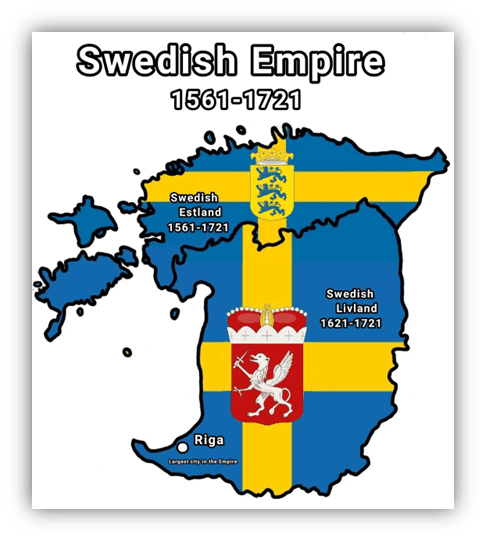

In the 1500s and early 1600s, several wars and the Protestant Reformation reshaped Northern Europe.

The Livonian War (1558–1583) brought chaos as Russia, Poland-Lithuania, Denmark, and Sweden all fought for control of the eastern Baltic.

From the 1560s to the early 1700s, most of Estonia belonged to the Swedish Empire.

Sweden introduced some reforms. It promoted education, printed Estonian-language religious texts, and reduced some abuses of serfdom. Still, the Baltic Germans kept much of their power as landowners. Estonian peasants remained second-class citizens, but they began to gain literacy and a sense of identity. Later, older Estonians fondly remembered this period as the “good old Swedish times.”

Everything changed again during the Great Northern War, lasting from 1700 to 1721.

It was a massive conflict between Sweden and a coalition led by Russia’s Peter the Great. Russia wanted access to the Baltic Sea and the trade routes it offered.

Estonia’s ports at Tallinn and Narva, were strategically valuable:

Especially since Russia’s only European port, St. Petersburg, would freeze over in the winter. The war was brutal, and Tallinn surrendered to Russian forces in 1710 after a plague killed thousands.

When the war ended, Sweden ceded its Baltic territories — including Estonia and Livonia (now mostly Latvia) — to Russia. From that point on, Estonia became part of the Russian Empire. Under Russian rule, Estonia wasn’t run directly from Moscow or St. Petersburg.

Instead, the Tsars allowed the Baltic Germans to continue managing local affairs. The region kept many of its old laws, its German-speaking upper class, and its Lutheran church system.

So while the emperor in Saint Petersburg was officially the ruler, everyday life for most Estonians still involved answering to German landlords.

Russian rule felt distant — at least at first.

That changed in the 19th century, when the empire began pushing “Russification” policies, like promoting the Russian language, Orthodox religion, and loyalty. These efforts were meant to tie the Baltics more tightly to Russia but, as is often the case, they had the opposite effect. A new national consciousness spread among Estonians.

The mid-19th century brought enormous change.

Industrialization, the spread of printing, and growing literacy among Estonian peasants helped create a new educated class.

Teachers, pastors, and journalists began writing in their own language.

Writers and activists urged Estonians to take pride in their culture and language. They helped start the Estonian National Awakening — a peaceful movement of cultural pride and the belief that they were a unique nation who should govern themselves.

And that’s why music in 1869 is important.

In June of that year, the first national song festival was held in the city of Tartu. Known as Laulupidu, it was framed as a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the abolition of serfdom. It meant more than that, and every Estonian knew it.

For the first time, choirs from across Estonia — peasants, students, and townsfolk — came together to sing in their own language, not in German or Russian. Around 800 male singers and 56 instrumentalists performed patriotic choral works, many inspired by Estonian folk melodies. The audience numbered in the thousands.

Songs like “Mu isamaa on minu arm” (“My Fatherland Is My Love”) filled the air.

“Mu isamaa on minu arm” is a poem by Lydia Koidula set to music by Aleksander Kunileid for the first Laulupidu. (A new melody was composed by Gustav Ernesaks in 1944.) For people who had lived under foreign rule for centuries, singing together as Estonians was a profound, liberating act.

| Mu isamaa on minu arm, kel südant annud ma. Sull’ laulan ma, mu ülem õnn, mu õitsev Eestimaa! Su valu südames mul keeb, su õnn ja rõõm mind rõõmsaks teeb, mu isamaa, mu isamaa! | My fatherland is my love, to whom I have given my heart to. I sing to you, my supreme fortune, My blooming Estonia! Your pain boils in my heart, Your fortune and joy make me glad, My fatherland, my fatherland! |

Laulupidu has been held every five years, through czars, wars, and occupations.

By the late 20th century, it was a beloved ritual that connected people to their roots. Even under Soviet rule, the festival survived, though authorities censored the repertoire and banned patriotic songs. Still, Estonians managed to sneak in coded messages through music and the quiet symbolism of togetherness.

That’s why the 1869 festival is often seen as the spiritual beginning of Estonia’s path toward independence.

Even under the Russian Empire’s watchful eye, music gave Estonians a way to express unity, pride, and resistance.

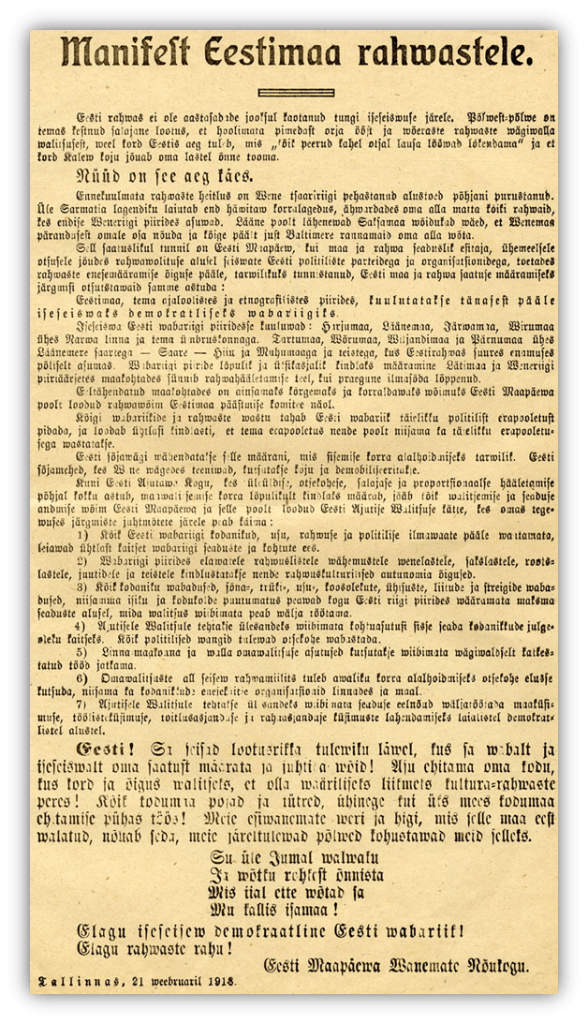

After centuries of foreign rule, Estonia finally achieved independence in 1918, at the end of World War I. When the Russian Empire collapsed in the chaos of revolution, Estonian leaders seized the moment.

On February 24, 1918, they issued the Declaration of Independence, establishing the Republic of Estonia.

The very next day, German forces occupied the country. When Germany surrendered that November, Russian Bolshevik troops invaded Estonia, trying to bring it into the new Soviet state.

The Estonians fought back in the War of Independence, another brutal conflict against both Russian and German forces. With help from volunteers and some British naval support, Estonia won.

In 1920, the Treaty of Tartu was signed between Estonia and Soviet Russia.

The treaty explicitly recognized Estonia’s independence “for all time.”

Estonia was a free, democratic republic, but it turned out that “for all time” lasted only two decades.

Again, the problem was geography. Estonia sat between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union — both of which wanted control of the Baltic region. In August 1939, those two rivals signed an agreement called the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. Publicly, it was just a neutrality agreement. Secretly, it contained a map dividing Eastern Europe into “spheres of influence.” Estonia, Latvia, and Finland were assigned to the Soviet sphere, while Germany would take on Poland and Western Europe.

A few weeks later, Germany invaded Poland and the Soviet Union invaded the Baltics. World War II began with Estonia stuck in the middle.

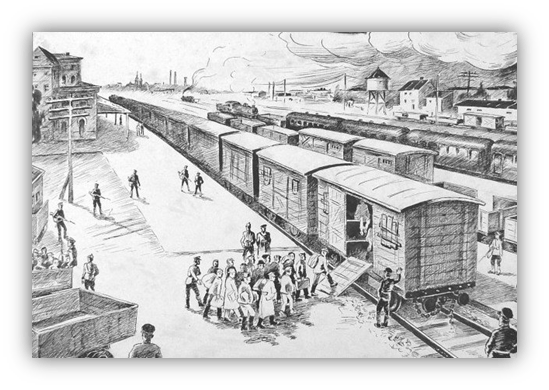

On August 6, 1940, Moscow formally annexed Estonia, declaring it the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic.

The annexation was illegal under international law.

It was a military takeover but the Soviets maintained the fiction of a voluntary union.

The Soviets nationalized land, banks, and industry, private property was seized, and political parties were banned. In a single night in June 1941, more than 10,000 Estonians — politicians, officers, intellectuals, farmers, and their families — were arrested and deported to Siberia.

Many never returned. Some died en route. For ordinary citizens, fear and silence became survival strategies.

Predictably, Hitler turned against Stalin. Nazi forces drove the Red Army out of the Baltics by the end of 1941.

Some Estonians initially hoped the Germans might restore independence, but that hope quickly vanished.

Nazi Germany treated Estonia as occupied territory, exploiting its resources and people for the war effort.

Thousands of Estonians were conscripted, imprisoned, or sent to concentration camps.

As the Nazis lost the war, Estonia briefly attempted to restore independence. The last Estonian government met in Tallinn and declared neutrality in hopes of Western recognition. That attempt failed.

By autumn 1944, Soviet forces re-entered Estonia, driving out the Germans.

The second Soviet occupation began, and this one would last nearly half a century.

The early postwar years brought more deportations, forced collectivization of farms, and Russia-centric policies that tried to erode Estonian language and culture. Large numbers of Russian-speaking settlers were moved in, which changed demographics. Estonian schools and media came under tight state control.

Yet beneath the surface: national identity survived through family traditions, underground publishing, and especially music.

Folk songs, choirs, and the five-year Laulupidu continued, even under censorship. A new stage was built on the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds in 1959 to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Estonian SSR in the upcoming year. The Soviets saw these festivals as harmless cultural events, but Estonians knew better. Singing was how they remembered who they were.

The Soviet Union began to weaken in the 1980s, partly due to its long, expensive, and misguided military failure in Afghanistan.

President Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) loosened some controls. Protests started to appear, often focused on local ecological issues — a planned phosphate mine in Estonia was canceled — but the protests quickly became platforms for bigger political demands, like the right to speak native languages, fly the old flags, and decide one’s own future.

The Estonian flag is blue, black, and white.

The flag was banned under Soviet rule, but at Laulupidu and other gatherings some people would carry blue banners, some carried black banners, and some white.

And if they happened to stand next to each other, well, that was just a coincidence. Estonia’s culture subversively called for independence once again.

In June 1987, during the Tallinn Old Town Days festival, singer Heidy Tamme and progressive rock band In Spe played “Eesti lipp” (“The Estonian Flag:”)

A song that had been banned for decades. The crowd joined in spontaneously.

That act — simple, joyous, and risky — is often cited as the unofficial beginning of Estonia’s Singing Revolution.

Cultural gatherings soon grew into vast, peaceful demonstrations. Estonians realized that singing — their oldest form of unity — could also be their most powerful weapon. The same people who had once gathered under the red flags of Soviet “friendship” now raised blue, black, and white banners — and sang the banned songs openly.

Another festival was held in June 1988 at the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds:

The same massive amphitheater built for Laulupidu.

Over the course of several nights, after an official music festival had ended, people refused to go home. Instead, they stayed, lit candles, and sang through the night.

Crowds grew to over 100,000 people, in a country of barely a million. Ten percent of the country was there singing banned songs, old folk tunes, and brand-new anthems written by local composers.

These weren’t performances. They were acts of defiance.

No one shouted slogans. No one threw stones. They just sang.

That’s how the Singing Revolution got its name.

At Laulupidu that year, the festival was a kind of national referendum. It was officially a celebration of the “friendship of Soviet peoples.” Unofficially, it was a declaration of independence.

As the choirs performed, flags began appearing in the audience — the blue, black, and white of Estonia, long banned from public view. No one stopped it.

By the end, tens of thousands were waving flags and singing songs that had been forbidden for 50 years.

The organizers hadn’t planned it that way, but history rarely asks permission.

Those moments made clear that the regime was losing its hold — not through violence, but through music.

Estonia’s example spread quickly to its neighbors, Latvia and Lithuania. They, too, had strong singing traditions and soon held similar rallies filled with folk songs, anthems, and candlelight.

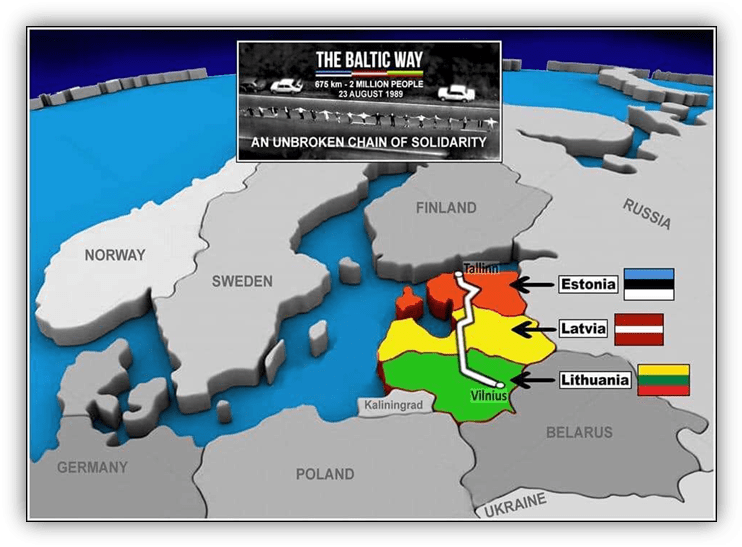

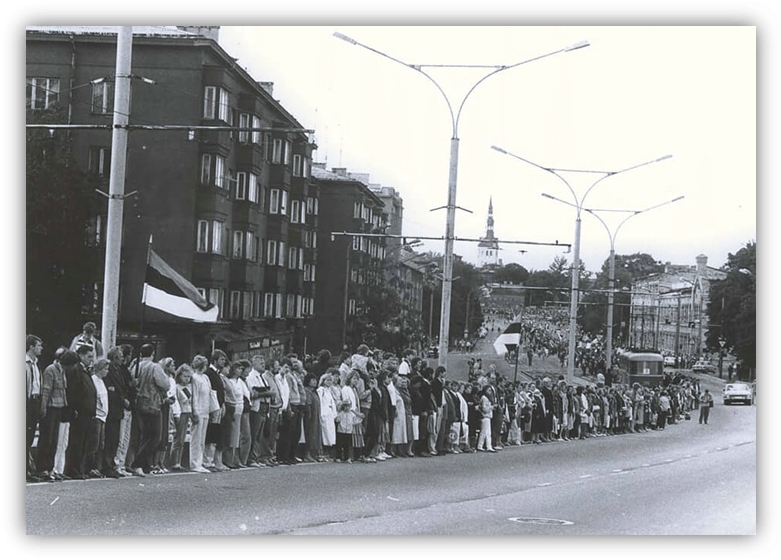

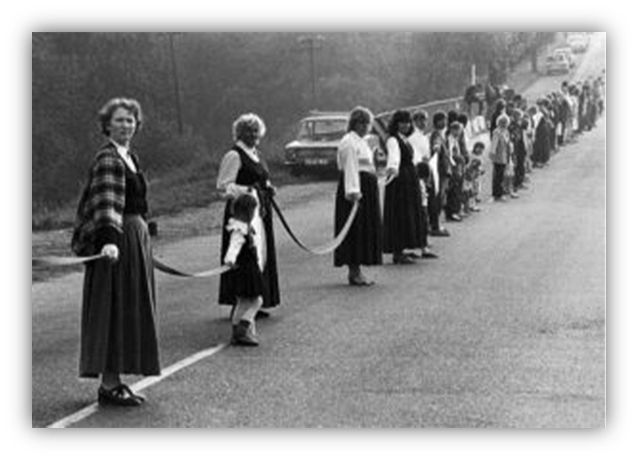

On August 23,1989, about two million people joined hands in a human chain stretching 420 miles through all three countries.

Known as The Baltic Way, it marked the 50th anniversary of the secret Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact that had enabled Soviet occupation of the Baltics.

People sang as they stood in that line — a living string of voices demanding recognition. News footage went around the world.

Everyone understood that these were not minor protests. These were nations coming back to life.

Nine months later, Lithuania was the first to declare its independence.

All three were sovereign states by the end of 1991. The Soviet Union dissolved a few months later.

But let’s not romanticize it. There were years of quiet organizing, risk, and political work to reach that point.

Singing was only part of it, but standing shoulder to shoulder and singing the same melody kept fear at bay.

Estonia still holds Laulupidu every five years. It’s one of the largest choral events in the world, with over 30,000 singers performing for crowds of nearly 100,000 people at the same hillside grounds where the revolution was born. The festival has become more than a concert — it’s a living symbol of unity and freedom.

During the Soviet regime, “Mu isamaa on minu arm” became an unofficial national anthem. Since 1947, it’s always the last song performed at Laulupidu.

When “Mu isamaa on minu arm” echoes across the crowd today, older Estonians remember the nights they first sang it under the threat of arrest. Younger people feel the pride of belonging to a country that earned its independence through harmony instead of bloodshed.

The festival is also a reminder:

I knew about the human chain. I’ve seen footage and it’s one of the most inspiring forms of protest I’ve seen. Probably the most inspiring given the scale and peaceful nature.

The singing I wasn’t familiar with. Again, an inspiring story of human spirit and of finding a way to fight the seemingly indestructible power while preserving your identity.

Great stuff Bill.

“… History rarely asks permission.” Indeed. Thanks for another deep look into an area of world history and culture that I never knew, Bill.

Have a good weekend.

Estonia, as well as Latvia and Lithuania, have shown a lot of courage taking in Ukrainian refugees. Their respective governments are aware of the Budapest Memorandum, which nobody talks about.

So few talk about it that I had to go look it up. You’re right, that seems important.

This is an inspiring story. Now I’m picturing a chain across the United States. Millions of people reclaiming democracy. But, honestly, we need a better anthem than “The Star-Spangled Banner” which is nearly impossible to sing.

Authoritarian regimes are the worst.

Before knowing the topic of your article, the photo associated with it made me think Latvia. I’ve known a couple of very proud Latvians. Those Baltic citizens have spirit!