Music Theory For Non-Musicians

…if there was ever an art where breaking the rules is one of the rules, it’s music.

redditor u/COMPRIMENS

This occasional series is about how music is made, and it’s for people who don’t already make music. It’s part music appreciation and part music theory.

I hope to cover rhythm, melody, intervals, chords, inversions, and more. Maybe we’ll get into extended chords and modes. Let’s see!

S1:E7: Anyone Can Play Guitar

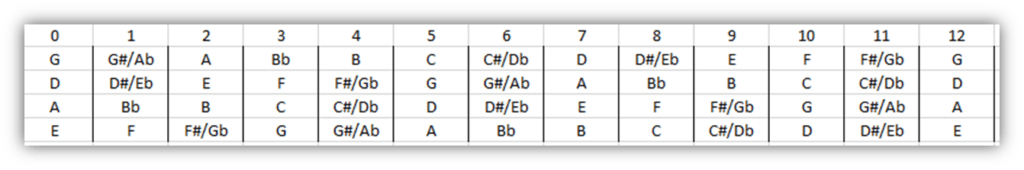

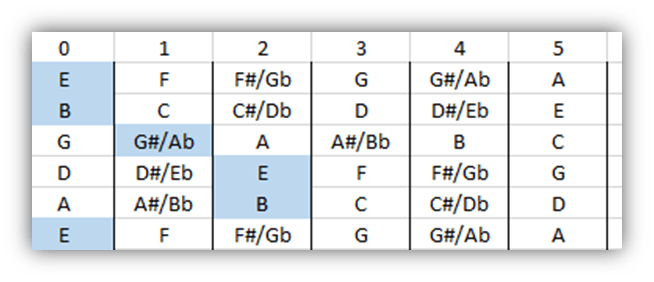

In our last installment, we talked about how the bass guitar is tuned. Each open string plays the same note as the fifth fret of the next lower string. You might remember this diagram.

I’ll start out with something really nerdy that general listeners probably don’t need to know, but it becomes important in more advanced music theory. Even though we tune each string to the fifth fret of the next string, we say the bass is tuned in fourths. Why?

Let’s look at, say, the A string and its neighboring D string. The fifth fret of the A string is a D, the same note as the D string. Think about the notes in the A major scale: A, B, C#, D, E, F#, and G#. The pitch of the next string, D, is the fourth note of that scale. So the distance from A to D is an interval of a fourth, and that’s why we say the bass guitar is tuned in fourths.

The upright bass is tuned the same way. The cello is also tuned in fourths, but its low string is an A. That means its strings are A, D, G, and C.

Violins, mandolins, bouzoukis, and many other instruments are tuned in fifths. That changes our diagram a little.

On these instruments, the low string is a G. The fifth of G (found at the seventh fret) is a D, so the next string is a D, and so on.

Violas are also tuned in fifths, but their strings are C, G, D, and A. Even the most serious classical music fans don’t need to know this stuff, but composers have to be careful to not write a note higher or lower than an instrument can play.

Why the different tunings? Violins are much smaller than upright basses or bass guitar. The length of the string from bridge to nut is about 13 inches on a violin. It’s just over 41 inches on a standard upright bass. That’s quite a difference.

The human hand can easily cover seven positions on a violin, so it’s tuned in a way that puts as many notes as possible under the hand. Someone long ago decided the best way to do that is in fifths. It’s not possible to cover seven positions without moving the hand on a huge bass, so it’s tuned in fourths.

It’s fairly easy for a violin player to also play mandolin because they’re all tuned the same way. You’ll often see someone play both instruments in a bluegrass or country band. It’s less likely that a violin player is also fluent on bass or guitar, or vice versa, because it means learning a whole new set of patterns and relationships.

Speaking of guitars, how are they tuned? The lowest four strings are tuned in fourths, exactly like the bass, just an octave higher.

Then it gets weird.

The next string up from the G is tuned to neither a fourth or a fifth, but to a third. So on the G string, we go up the scale to A and B, and there’s our third at the fourth fret. That makes the next string a B.

However, the last string is tuned to the fourth of B, so it’s another E string. It has exactly the same notes of the low E string, but two octaves higher.

You’re probably thinking that this tuning in fourths except for one string tuned in thirds was done just to make things confusing for you. Once you play for a while, you’ll find it actually makes things easier. Here’s what I mean.

Chords that use open strings are called open chords, and they tend to be played with the left hand near the nut. New guitar students are usually taught open chords first, so we’ll start there.

Let’s say you want to play an E major open chord. The three notes in the E major triad are E, G#, and B. You’d need to find one of those notes on each string.

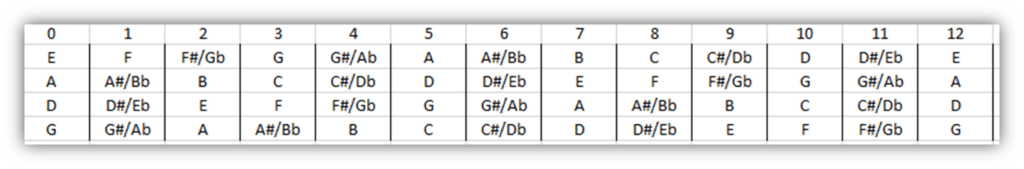

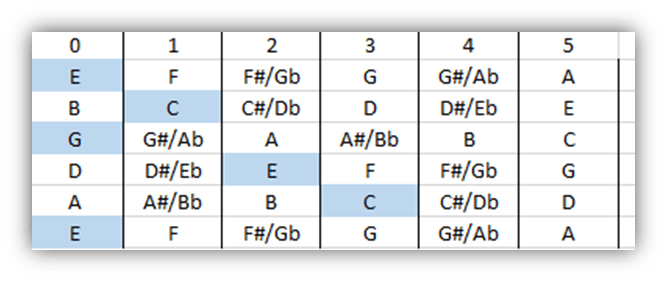

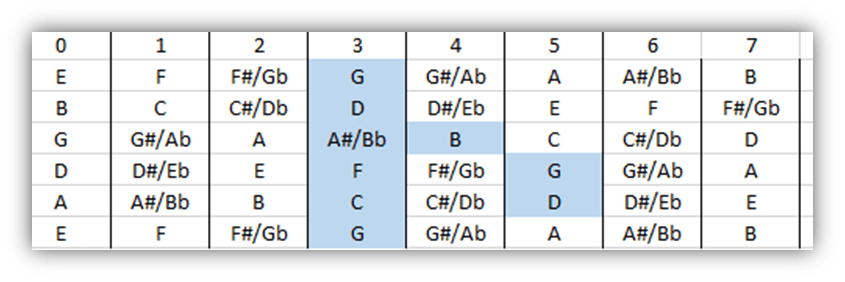

If all the strings were tuned in fourths, they’d be, from low to high, E, A, D, G, C, and F. I’ve changed the diagram to show what it would look like, with the notes of the E major triad shown in blue.

The low E string would be open, your index finger would play the G# at the first fret of the G string. Then you’d somehow have to use your middle finger to get both the A and D strings at the second fret, and then put your ring finger on the third fret of the F string and your pinky on the fourth fret of the C string. While you struggle to get that, you have to be careful to not let any of your fingers touch any other strings so you don’t mute them. It looks impossible to me.

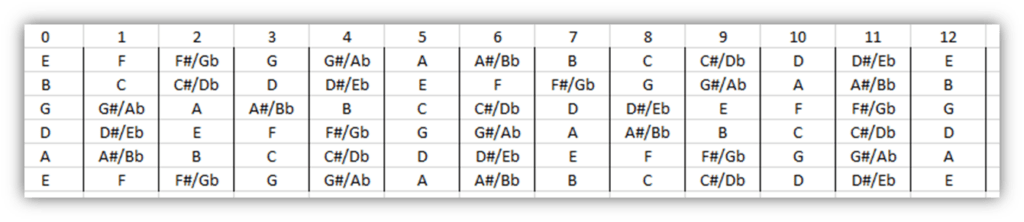

Now let’s look at the E major chord in standard tuning. The B string and both E strings are open. You put your index finger on the first fret of the G string, your middle finger on the second fret of the A string, and your ring finger on the second fret of the D string. It’s much, much easier.

And this is true of most open chords. Some unnamed geniuses back in the Renaissance came up with this tuning, and it’s always easier to play chords with it.

For example, the C major chord’s three notes are C, E, and G. That makes it easy on guitar.

And the G major triad is G, B, and D, which is also very easy.

In reality, you don’t need to know the notes in the chord in order to play it. I would guess that most amateur guitarists, and quite a few professionals, don’t. Once you learn that you play a G major chord by putting your fingers here, here, and here, and leaving the other strings open, your muscle memory takes over. After a while, having your fingers in that position just feels right.

“But, “I can hear you saying, “what about scales?” You’ll remember that we played scales on the bass guitar in the last installment. Once you learned the pattern of the scale, you could slide it all over the neck to play the major scale starting on different tonics.

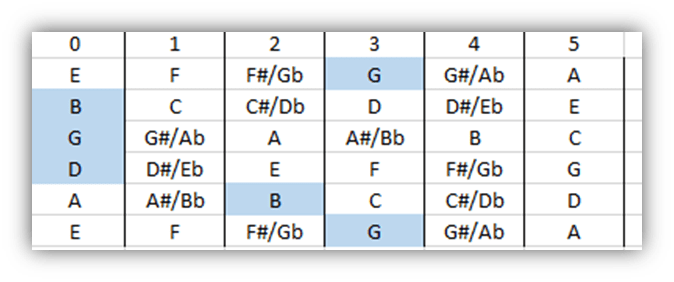

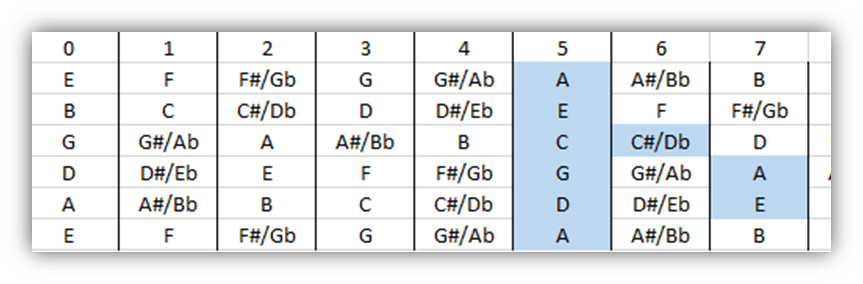

It’s exactly the same thing on the guitar, but since there are more strings, you can play two octaves without moving your hand up or down the neck. Here’s the G major scale, starting with your middle finger on the third fret of the low E string.

Now that you have this pattern, you can move it all over the neck to play other major scales. Let’s slide it up two frets to play A major.

You might now be wondering if you can take the G major chord and slide it up two frets to get an A major chord. The answer is no, not with the G major open chord I showed you. It uses open strings, and you can’t slide an open string.

You can, however, use something called a barre chord. It’s pronounced “bar” and it’s where you lay your index finger across all six strings like a bar, and use your other three fingers to select specific notes.

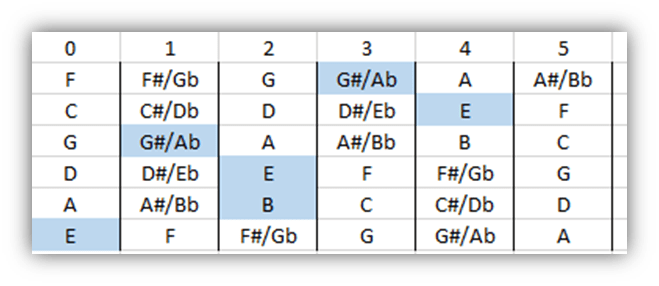

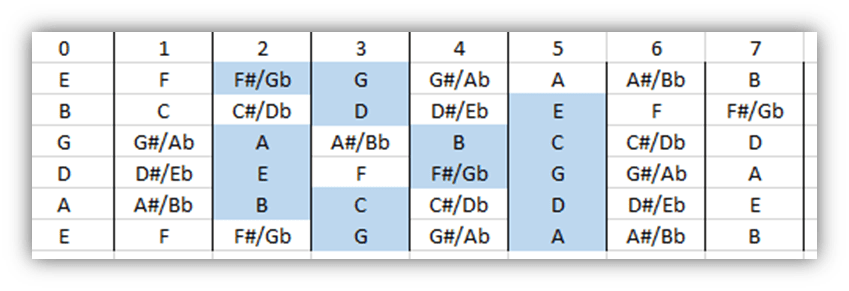

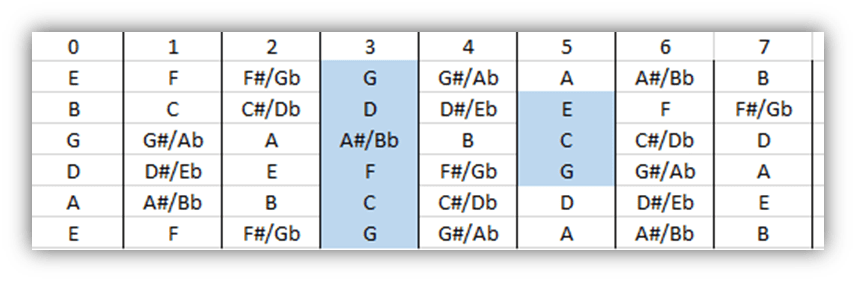

This is the G major barre chord. Put your index finger across all six strings at the third fret. The third fret is where the G is on the E string, so that’s easy to remember. Then put your middle finger on the next fret of the G string, and your ring and pinky on the next fret after that on the A and D strings. It looks like this:

And yes, now that there are no open strings, you can slide it up two frets to play the A major chord.

With that one shape, you can play any major chord just by moving to the correct fret. Neato.

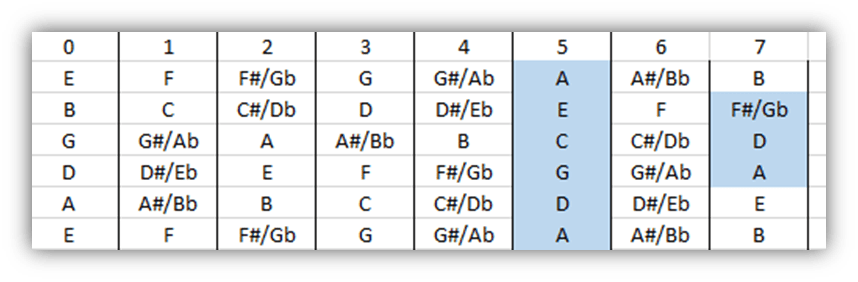

There’s another barre chord shape for playing major chords. In this one, you again lay your index finger across all six strings, and then use your other fingers to play the second fret up from there on the D, G, and B strings. This is what it would look like for C major.

With this shape, the chord’s root note is under your index finger on the A string. So if you slide up two frets, your index finger will be over the D on A string. That makes this a D major barre chord.

Having these two shapes is cool because very often a song will have a G and a C. So you could play them by switching from one barre chord shape to the other and never move your hand up or down the neck.

G and C are a fourth apart and it’s very common in western music, especially in rock, pop, and folk two use two chords a fourth apart for some, if not all, of the song. It might be G and C, or E and A, or F and Bb, or whatever. All these are two chords a fourth apart. I’ll Take You There by The Staple Singers, for instance, is C and F for the entire song. Play these two barre chords at the seventh fret and you’re golden.

There are also barre chord shapes for minor chords and seventh chords and minor seventh chords and so on. The next time you see a guitarist on TV, especially in a rock band, watch their fretting hand. You’ll see a lot of barre chords. Once you know what they look like, you’ll see barre chords everywhere.

A great thing about barre chords is they make it easy to transpose a song to another key. If you decided that your song using G and C is too low for your voice, you could slide your hand up to, oh, the sixth fret. That would make one shape a Bb major and the other shape an Eb major. If that’s too high for your voice, you could slide down a fret so you’re playing A major and D major. All the while doing, you’re doing exactly the same thing with your left hand, just at a different place on the neck.

Cool, right? By the way, barre chords are only possible because that one string is tuned to a third rather than a fourth. Standard tuning may seem odd at first but with it, Radiohead is right:

Anyone can play guitar.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “heart” upvote!

The barre chord.

To my mind, this is the first major hurdle in learning the guitar.

I have known many to quit at this stage, only because it can be uncomfortable to play when first learning how to fret a barre chord.

However, I have seen the opposite. It’s always great to see the eureka moment that comes with mastering the barre chord, both in terms of dexterity and theory. As Bill points out, it becomes a skeleton key of sorts, making almost everything playable.

I always think of this guy:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin_Barre

Nah, he’s the one that invented that thing ballet dancers hold on to.

A priest, a rabbi, and a bass player all walk in to a barre…

Well, the first problem is that the first barre chord most beginners learn is the F Major. If you’re learning songs in the key of C (all white keys on the keyboard), it’s that IV chord you need to know for simple folk songs.

It requires your first finger to stretch out, press, and hold down all the strings at the place where there’s the most tension, the first fret. The string is held up high off the fretboard, at the nut, and if you have a cheap guitar (as most beginners do) it’s that much more difficult to press down.

Suggestion: learn your first songs in the key of A. Then, if you want to learn how to play a barre A chord, do that same finger pattern you were going to do for the F up at the 5th fret.

Here’s the secret to playing barre chords painlessly: Don’t squeeze the strings, don’t press the strings. Just let the natural weight of your hand and lower arm hang, and let the gravity press the strings down. It’s a little trick of the mind that works.

Here’s the thing – I played classical guitar for about 5 years as a youngster, and rock guitar about 35 years before taking a bit of a break. When I came back to playing a couple of years ago, I found a wealth of help on YouTube and other web locations. I never heard of this barre chord trick until then, and it’s helped all my playing.

The trick to all good playing is relaxation. I’m not the only fool who tightens up at the thought of playing faster, fancier, louder, more, more, more. But strength is not the key, relaxation is.

Another good article, V-Dog, except for that “anyone can play guitar” stuff. The First Rule of Guitar Club is nobody talks about that.

Excellent advice. Relaxing is difficult in an exciting situation like playing for an audience, but it really helps.

F major on a crappy school guitar was definitely part of the issue for me. That, and never practicing, basically put my guitar career on permanent hold.

If only you’d been available 25 years ago when I was trying and failing to learn how to play. Anyone may be able to play guitar but I’m not sure anyone else would want to listen to my ham-fisted efforts. I probably just needed the right environment, some 1:1 tuition and a whole lot more patience than I had back then.

Probably. Y’know, it’s never too late.

V-dog, always insightful, but beyond my scope until I get a guitar (again). I do have a scientific question, however…

Hope this helps but keep the questions coming!

Just to clear something up – the frets are the metal strips across the neck of the guitar. They are raised, and pressing your finger between the frets causes the string to be pinched where the string meets the fret. (We usually say we are “at” a fret instead of in-between.) For example, if you press the string anywhere between the second and third fret on the highest string of a guitar, the string will be pinched against the third fret, and will ring a G note. It took me quite a while to understand this terminology.

Extra credit: Guitar players learn to place their fingers as close to the fret as possible because that’s where the least pressure is needed.

That just explained a lot – so the note isn’t created by exactly WHERE the finger is placed, the finger is placed to prevent any vibration of the string above the fret.

(Also, I kind of knew the lines across the neck were frets, but as described I thought maybe it was the area between where the fingers were placed. Also, great information on all this technique – when I did practice, I pressed so damn hard with my fingers I was exhausted.)

Excellent description, Archie!

Sensei, I appreciate the effort as always, but I think I need to save this one for later. I’m still trying to map my eyes and fingers to the piano keys, and my brain is shouting like a grumpy old thing as I try to figure this out. I’ll give him a beer to make him shut up.

Cheers!

Great as always, VDog. This is a fairly random question, but do you know if there’s a reason that the open strings of all these instruments are tuned to naturals? Like, is there a musicological reason, or is it just one of those things that happened, like some proto-luthier did it that way, and everyone else just followed, or there was some quasi-Pythagorean cult in the middle ages that thought natural notes were more godly?

It’s a very good question, and I don’t know the answer. I could guess that it’s just human nature to like round numbers and natural notes, but who knows?

I’ve seen some alternate tunings with strings tuned to sharps or flats, but it’s not standard at all. I’ve seen that some metal bands tune down to C#, making the strings C#, F#, B, E, G#, and C#. The lower tuning makes it sound heavier, so you won’t find stuff like that on the Hot 100.