Music Theory For Non-Musicians

…if there was ever an art where breaking the rules is one of the rules, it’s music.

redditor u/COMPRIMENS

This occasional series is about how music is made, and it’s for people who don’t already make music. It’s part music appreciation and part music theory.

I hope to cover rhythm, melody, intervals, chords, inversions, and more. Maybe we’ll get into extended chords and modes. Let’s see!

Episode 12: I Saw The Sign

The point of this series is to help non-musicians understand how music is made. I know I shouldn’t get too deep into the technical aspects, but I do. Can’t help it. I love this stuff.

Sometimes a technical topic just comes up. In our last installment, I showed some standard sheet music for a cello part and mentioned that it changed from one clef to another. I used it to show how complicated standard notation is, and how much easier it is to use the Nashville Number System.

However, our friend thegue asked some interesting questions about standard notation.

- “And it changes from bass clef to, what is that, tenor clef?” (where? how? what’s a “clef”?)

- # = G Major? What are the symbols that represent the other keys?

So basically: what are clefs, and how do key signatures work?

To answer, we have to get into some technical stuff, we have to talk about all the hieroglyphics on the page…

I’ll try to make it easy.

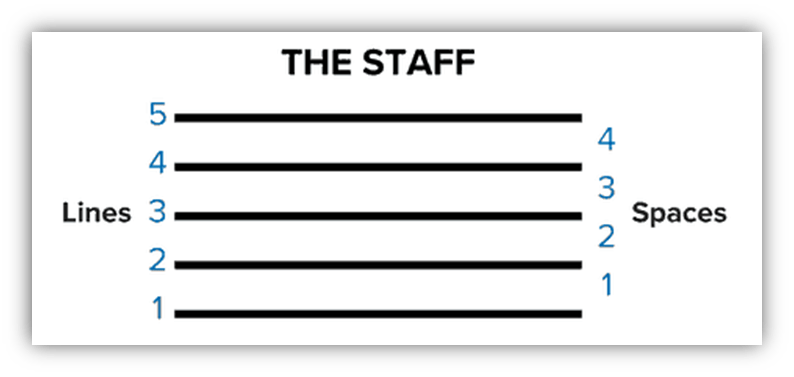

There are many methods used around the world for writing down music. The one we use most here in the western world is something we call standard notation. That might be a little presumptuous of us. Anyway, in standard notation, the notes are placed on five parallel horizontal lines. It’s called the staff.

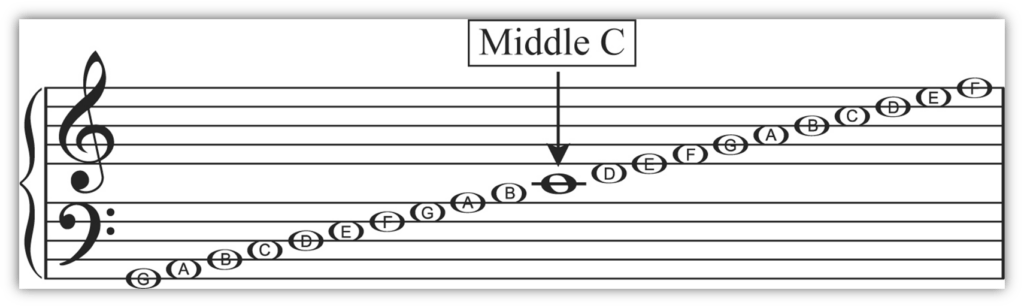

Having five lines means there are four spaces between them. That gives us nine spots to place notes.

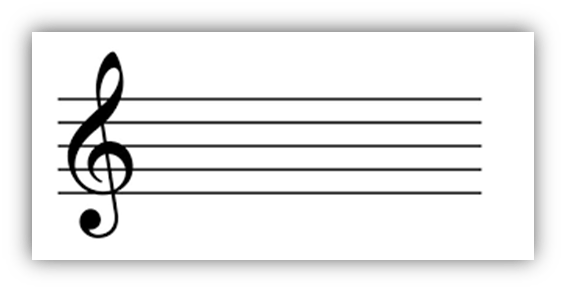

How do you know what notes go on which lines or spaces? That’s where the clef comes in. The most used clef is the treble clef. Here it is on a staff.

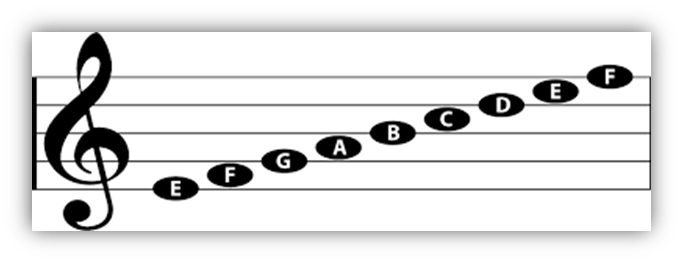

You’ve all seen the treble clef. It’s the universal sign for music. See how it curls around the second line from the bottom? That indicates the second line represents the note G. That’s why the treble clef is also known as the G clef. I don’t know why, I only know we’ve been using it this way for centuries.

If the second line up is a G, that means the space above it is A, the line above that is B, the space above that is C, and so on.

There are mnemonics for remembering these notes. The notes in the spaces, F, A, C, and E, spell out FACE. The lines are E, G, B, D, and F. I always learned this as the first letters in Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge. I think the British use Every Good Boy Deserves Favour. Can one of our English friends confirm this?

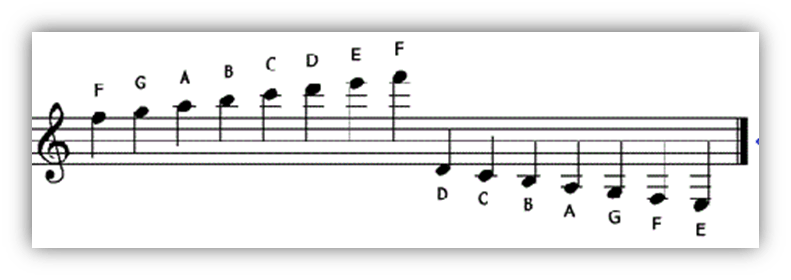

But there are way more than nine notes. The piano alone has 88. How do you fit all those notes into nine places?

Simple. You just add lines when you need them.

These are called ledger lines and, yes, they get tricky to read. I can handle two ledger lines above or below the staff. Anything more than that makes my eyes cross.

The C on the first ledger line below the staff is known as middle C. It’s the middlemost C on a piano. Keep this in mind. I’ll mention it again momentarily.

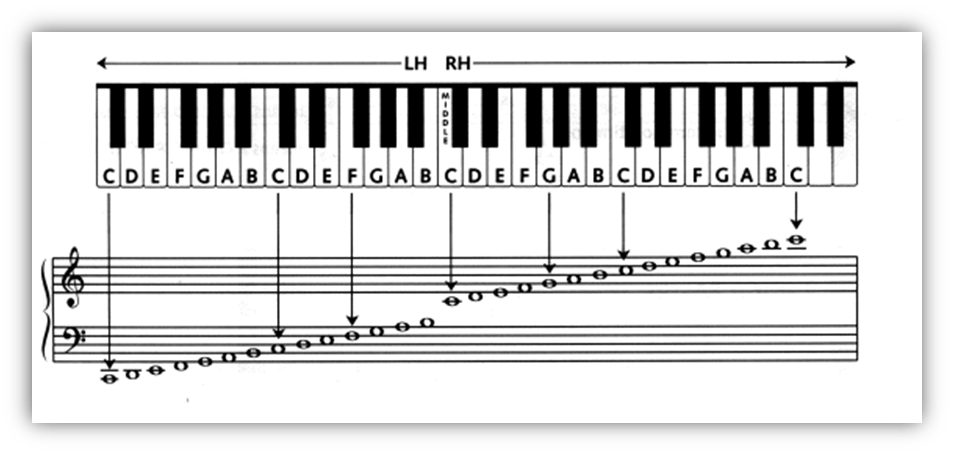

Imagine if you’re a piano player, you have 88 notes, and you have to count dozens of ledger lines above and below the staff. Talk about crossed eyes! That’s why piano players get a second staff.

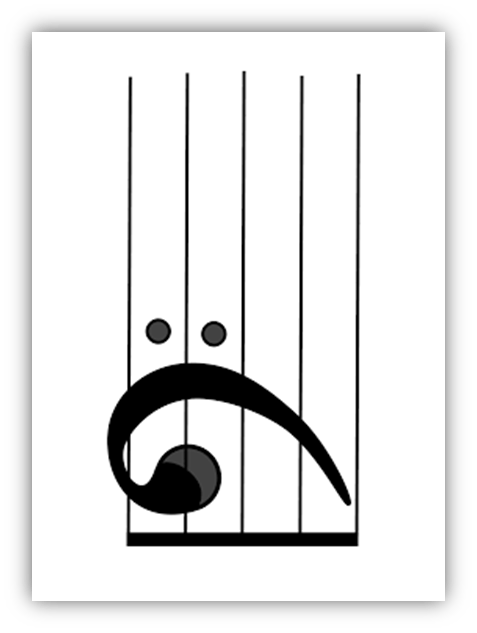

The lower clef is called the bass clef, also known as the F clef. It sort of looks like a backwards C with two dots. The dots indicate that the line between them is an F.

Remember that middle C is the first ledger line below the staff when using the treble clef? When you’re using the bass clef, middle C is the first ledger line above the staff.

Using these two staffs together means you can cover everything from two octaves below middle C to two octaves above middle C and only use two ledger lines below the bass staff and two ledger lines above the treble staff. Most music will be in this range.

Generally speaking, the right hand plays the treble clef (everything above middle C) and the left hand plays the bass clef (everything below middle C). How keyboardists read two different clefs and play them with both hands doing different things is beyond my comprehension.

However, I’ve noticed that if you turn the bass clef sideways, it looks like a frog who’s sad because he’s in jail.

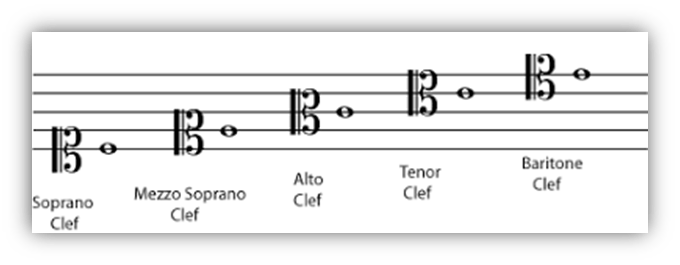

The bass and treble clef are the two most widely used clefs. They’re all you’ll ever see in rock and pop. There are, however, several other less used clef called the C clefs.

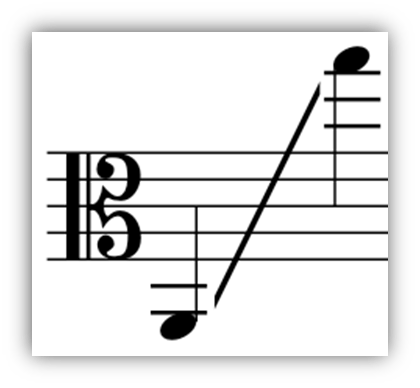

Each of these use the same symbol but move it to a different line. In each of these, the line between the curlicues is middle C

Why bother?

It has to do with the range of particular instruments.

The lowest note on an alto trombone, for example, is two A’s below middle C, and its highest note is two G’s above middle C.

Using the alto clef means you need the fewest number of ledger lines. Therefore its sheet music is easier to read.

In the cello music from the last article, you’ll see that it starts with the bass clef. Then, on the third staff down, it switches to the tenor clef. Then it switches back four measures later.

Again, the composer switched clefs to avoid hard-to-read ledger lines. That first note after it changes to the tenor clef is a D an octave up from middle C. It took three ledger lines to get up there. Had the sheet music stuck with the bass clef, that D would require five ledger lines.

Three ledger lines is hard enough. Five is eye crossing territory.

The other thing thegue asked about is the # next to the clefs. That’s the key signature, and in this case it’s telling us that this Allegretto is in G major. How do we know that?

By now, regular readers are tired of me harping on the steps of the major scale (tonic note, then up a whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, whole step, and half step), but it’s kinda important. It’s do re mi fa so la ti do. Basic stuff.

If your tonic is C, then your notes are C, D, E, F, G, A, B, and C. But if you start on G, your notes are G, A, B, C, D, E, F#, and G. The F is sharpened. It’s a half step higher than an F natural, so on a piano it’s the black key between F and G.

Now, the composer could put a # next to every F on the sheet music, but that would get cluttered and, again, hard to read. By putting a # on the F line at the beginning of the piece, the composer is telling us that every F will be sharpened.

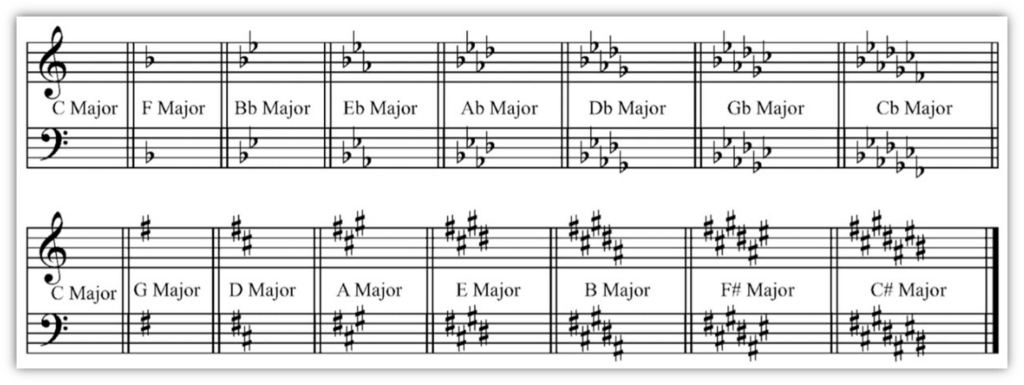

This notation at the start of a piece telling you which notes are sharp or flat is called the key signature. It tells you what key the music is in. Here’s a chart of all the possible key signatures, on both the treble and bass clefs.

Experienced musicians will see, say, three flats and just know that the piece is in the key of Eb. That’s the only key with three flats. They don’t have to look at what lines or spaces the flats are on in the key signature. The flattened notes are always Eb, Ab, and Bb.

Likewise, you can just tell a musician the song’s in Eb and they’ll know the notes. They’re Eb, F, G, Ab, Bb, C, D, and Eb.

Songwriters love changing keys in the middle of a song. They’ll often raise the song’s key a half step or whole step just to add some excitement. Those aren’t the only intervals for key changes, of course. It could be any key changing to any other key, but how do you do that in sheet music?

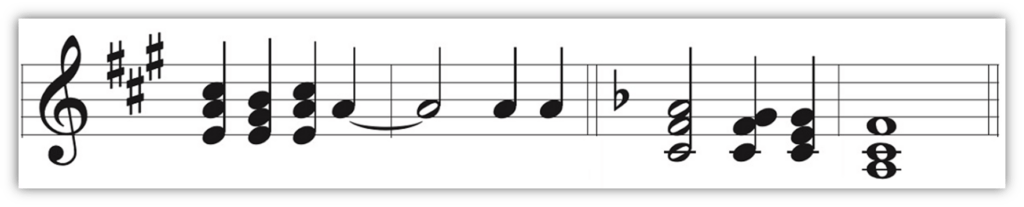

Here’s an example where the first two bars are in A major, indicated by the three sharps, and then changes to F major in the third measure when the single flat is the first symbol in the measure.

That flat says, “Forget everything I said about sharpening those three notes. From here on out, just flatten all the B’s.”

Composers try to make things easier on musicians by limiting the number of lines and symbols, but it’s still a very complex system. It may be difficult, but standard notation allows composers to tell musicians exactly how to play their music.

It’s likely that the composers will never meet the musicians. The composers may even be long dead when the musicians decipher the sheet music. Standard notation, when done well, should answer all the questions musicians might have about how the music should sound. Because you can’t ask clarifying questions of a dead guy.

The clef and the key signature are always the first two things you’ll see on sheet music. They tell you what notes are on which lines and spaces, and which notes to flatten or sharpen. Easy, right?

The third thing you’ll see is the time signature, but I think I’ve crossed your eyes enough for one day.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “heart” upvote!

Yay, I actually knew some stuff!

Slight correction though, I believe the saying is: Every Great Bassist Drips Funk. 😀

I like that much more.

Wow! The most informative lesson yet, if only because it built upon that little knowledge I had from second grade of Every Good Boy Does Fine. I was able to follow everything here, so no questions yet. Great lesson V-Dog!

Here’s another great example of key changes in a song.

Another useful mnemonic my trumpet teacher taught me is for remembering the order that sharps get added (ie, if there’s on sharp it’s always an F; if there’s two, it’s always an F and C, etc.): Frogs Can Get Drunk And Eat Bugs. Maybe that’s why the frog is in jail?

I’ve never heard that one but it’s really good. Putting it in the old noggin for safe keeping.

If someone was really enterprising, they would come up with one that made sense forward and backward, so that you only needed set of words for both sharps and flats.

A few comments on Sunday, where nobody will see them…

I’m not all that great at memorizing the key names by looking at the staffs, but here’s a trick for knowing the diatonic key names –

Stevie Wonder frequently uses key changes in imaginative ways. “Lately” has a jaw-dropping change in the last verse – instead of the usual half-step nudge up in tension, he goes up a fourth(!), and his voice never falters on the high notes. On the song “Summer Soft” from Songs in the Key of Life he repeatedly raises the key as sings about how long his woman friend has been gone.

I’m a sucker for songs which change keys for different passages. The Beatles were great at this – examples of songs which alternate between relative major and minors between verses, bridges, and choruses are “Things We Said Today” and “Norwegian Wood,” for starters

As long as the “latest” feature on the front page works, you’ll never be completely anonymous. 😉

Thanks for explaining why I’ve always loved the Beatles’ “Things We Said Today.” I never thought about why I enjoy that song so much. Your explanation makes perfect sense to me.

> As long as the “latest” feature on the front page works, you’ll never be completely anonymous.

Exactly why it’s there – it helps to prevent all of our good friends from getting “comment buried.”

You’re SUCH a good mt, yes you are, buddy!

He tries very hard.

Those are great tips! I never noticed the detail about sharps before.

@Bill Bois I just realized – one flat is F, but two flats – the key is the next to last flat! Three flats, same! So four flats is A flat!

Wow, that’s an odd little howdy do. Another good one to remember!

I actually remembered some of those terms!! Makes me curious how long it would take me to remember to read music if I was given some sheet music nowadays.

Nom-nom-nom…

To any humans reading this, gate io is a spam bot. Don’t click its name above or any links it may post.

I worked all night on counter measures for this. Sorry to all about the spam. I’ll get it sorted out.