Music Theory For Non-Musicians

…if there was ever an art where breaking the rules is one of the rules, it’s music.

redditor u/COMPRIMENS

This occasional series is about how music is made, and it’s for people who don’t already make music. It’s part music appreciation and part music theory.

I hope to cover rhythm, melody, intervals, chords, inversions, and more. Maybe we’ll get into extended chords and modes. Let’s see!

Those of us that have siblings have wondered: how can someone who shares the same DNA can be so weird?

Sure, there are similarities; we might have the same eyes or the same hair, but how can a neat brother have a messy sister? How can one be a bookworm and the other be a jock?

It’s the same with majors and minors in music. They’re so similar and yet, well, not.

I’ve talked about major scales and chords a lot here. That’s because they’re both simple and crucial. The major scale is just do re me fa so la ti do. That’s how simple it is. And it’s always the first one you learn because it’s used more than any other. That’s how crucial it is.

The same goes for major chords. They’re the first ones you’re taught in music lessons or in a beginner’s music book. The first songs you learn to play, whether it’s “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” or “Old Town Road,” will use mostly major chords.

If you’ll remember, the major triad is three notes. (That’s why it’s called a triad.) The notes are the root, the third note up the scale from the root, and the fifth note up the scale from the root.

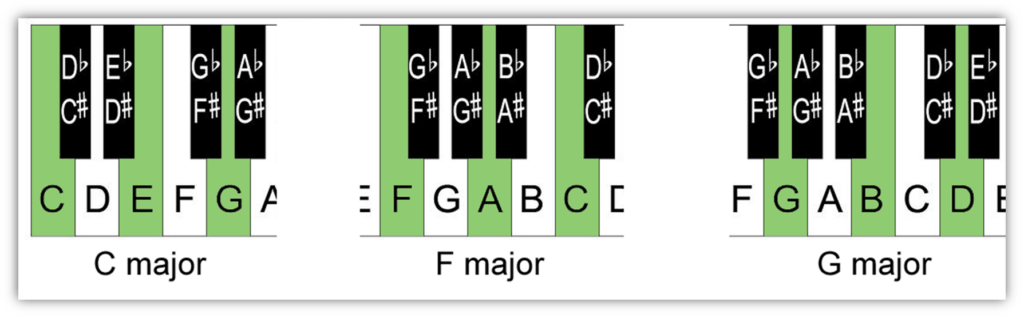

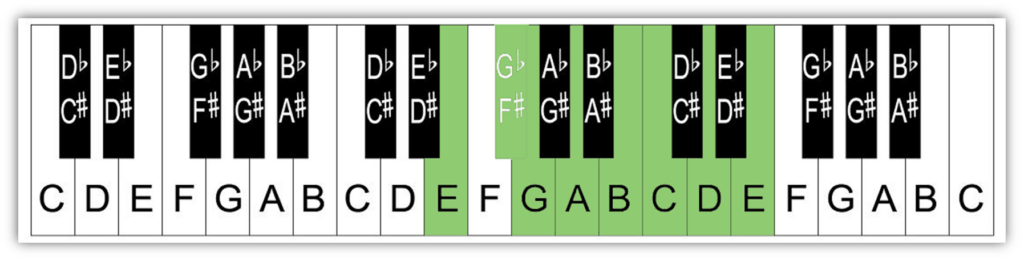

So in our favorite key of C major, and it’s our favorite because it’s all the white keys on the piano, the notes in a C major triad are C, E, and G. And as you can see in this diagram, the notes in a F major triad are F, A, and C, and a G major chord is made up of G, B, and D.

What’s cool about this on a keyboard is you can lock your hand in that position to play C major, and just move it up the keyboard to play the F major and G major. Play the first chord, pick your hand up without moving your fingers, and plonk it down somewhere else on the keyboard. Bingo. New chord.

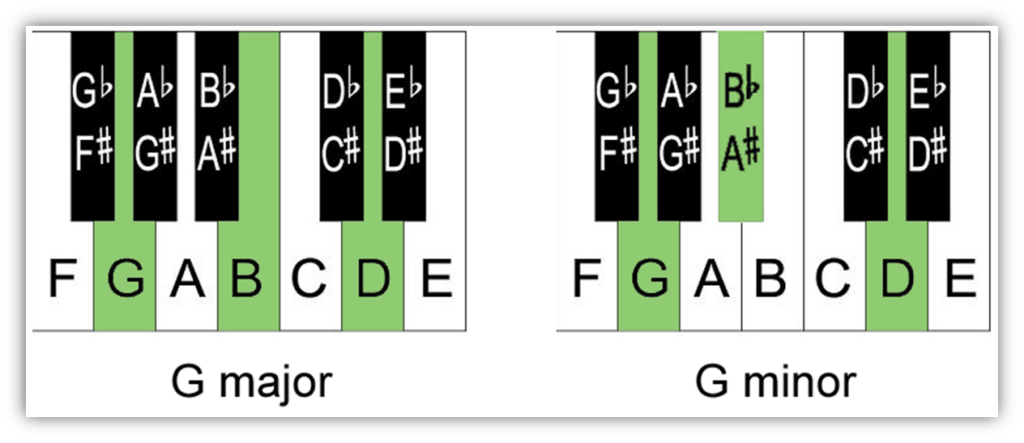

Let’s stick with that G major for a second (mostly because I’m reusing the graphic below). How would we change it to a G minor?

The difference between a major and minor chord is the third. We take the third of the chord, in the case of G major it’s the B, and flatten it. That would make it a Bb. The root and the fifth remain the same, so G major and G minor both have G and D. The only difference is the G major has a B and G minor has a Bb.

So if that’s the only difference between a major and minor chord, is it also the only difference between a major and minor scale?

Well, yes.

But actually, no.

Just to complicate things more, there are many minor scales. Yes, they all have a flattened third note (which is what makes them minor), but they have some other notes flattened, too. Which notes are flattened determines what name we give the scale.

The three most common minor scales are natural minor, melodic minor, and harmonic minor. I’ll only talk about the natural minor today. I don’t want to start your eyelid twitching due to too much information.

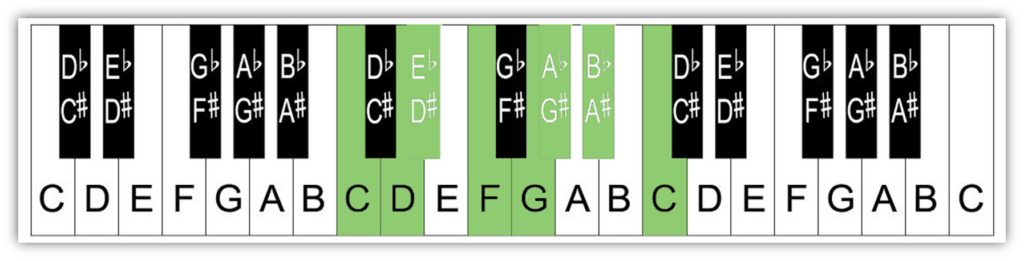

The natural minor has the 3rd note flattened, like I mentioned above, but it also has the 6th and 7th notes flattened. So let’s start with our favorite key of C major and make it into C natural minor. The notes of C major are C, D, E, F, G, A, and B. By flattening the 3rd, 6th and 7th, the notes of the C natural minor scale are C, D, Eb, F, G, Ab, and Bb.

Let’s look at the pattern of half steps and whole steps in these scales. Yes, it’s annoying but it will come in handy momentarily.

As a reminder, a half step is moving from one note, to the next closest.

A whole step is two notes away. The major scale goes up: whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, whole step, half step.

The natural minor scale goes: whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step. You can count it out on the diagram above or on a keyboard if you have one.

Trust me for a second and think about that pattern starting on an A. What notes does it give you? Well, a whole step up from A is B. Then a half step gives you C. Another two whole steps gives you D and E, and then a half step to F. Finally, it’s two more whole steps to G and A.

What do you notice about those notes?

Exactly! There are no sharps or flats. It’s all the white notes on the keyboard.

That means the A natural minor scale uses the same notes as the C major scale, just starting on the A instead of the C. It’s the same DNA, but a different character altogether. That’s why we call it the relative minor of C major. They’re relatives. They’re siblings.

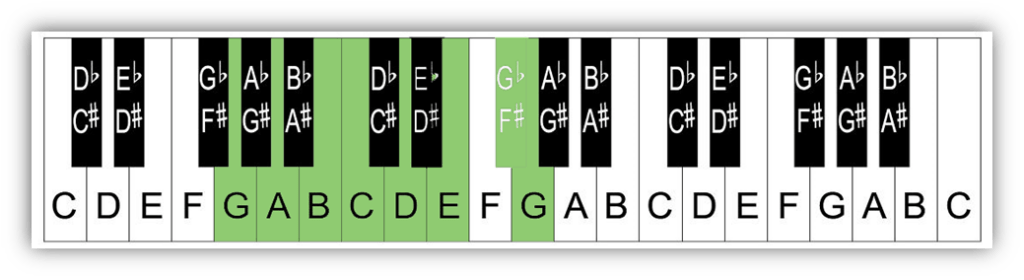

A is the 6th note of the C major scale, so this means that you can find the relative minor of any major scale by starting on that scale’s 6th. The 6th note of the G major scale, for example, is an E, so the relative minor of G major would start on E. Again, it’s the same notes but a different personality. (Alphabetically, the notes are A, B, C, D, E, F#, and G.)

OK, now that we have a grasp on that, let’s ask the next question. If there are relative minor scales, are there relative minor chords?

Absolutely, and the same rule applies. Just find the 6th note up from the major chord’s root and use it as the root of the minor chord. So, like the A natural minor scale is the relative minor of the C major scale, A minor is the relative minor chord of the C major chord.

Why is this important? In almost all cases, you can replace a major chord with its relative minor and it will still sound good. Different, more melancholy, but good.

Let’s try an experiment with our old friend “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.”

Here it is the way you’re used to hearing it, with all major chords. The chords are C major, F major, and G major.

And here it is with all of those major chords replaced with their relative minors. Those would be A minor, D minor, and E minor..

It gives the song a different atmosphere, but it totally works.

You can do it the other way, too. If a song sounds too sad, replace the minor chords with their relative majors. To find the relative major, just go to the 3rd note up from the root and use it as the root of the major chord.

Changing chords under a melody is called reharmonization, but that’s a topic for another day. Perhaps that day will be next Friday. See you then!

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “heart” upvote!

I don’t want to start your eyelid twitching due to too much information.

Too late.

Haha. Hold on, thegue. To borrow the family analogy, melodic minor and harmonic minor can be considered two very, quirky step-siblings, capable of a lot of beauty and a lot of darkness.

Great work as always, Bill.

Thanks, mt58, for adding the link to “Country Roads” in a minor key. It’s so melancholy. So to cheer everyone up, here’s “Losing My Religion” in a major key.

The YouTube comments for the minor key “Take Me Home Country Roads” are gold. My two favorites:

“This isn’t John Denver travelling along a country road to finally reach his home. This is John Denver crouching in a cardboard box in the rain in Downtown LA crying himself to sleep wishing he could see his childhood home one last time.”

“The backup singers keep trying to sing in a major key and he just gives them a dirty look, points his finger down and they give him that ‘oops sorry’ look and go back to a minor key.”

Oh lord, the comments for REM are just as good:

“In this happy version, the theme is simply trying to figure out where you put your gosh darned religion, and in the end it turns out it was in your other pants all along, and everyone laughs together before fading out.”

“Losing my Religion is filmed in front of a live studio audience.”

Here’s an interesting article about the relative popularity of major vs. minor keys, and how it has shifted over the past few decades. As a sensitive young lad, I sensed that my taste in minor key songs was in the minority, especially for my age. Maybe that was part of the guitar’s attraction to me – it’s easy to sound good playing in A minor.

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/pop-music-study-minor-key_n_2122726

That’s interesting indeed. I’d like to see a line graph of major vs minor #1s, or the entire Hot 100, by week since the 50s.

In grad school, I was a participant in an EEG study where I had to judge if a song was in major or minor key. After the session, my colleague told me he was trying to test if musicians exhibited different EEG patterns than novices when discerning the musical passages. Since they look for group-level effects, I never got to learn how I, a novice, performed. And I just now tried to find an article on the experiment on Google Scholar, but I don’t see anything. Maybe the results didn’t pan out. Maaaaaaaybe a certain novice screwed up the comparison with his bad-ass brainwaves. 🙂

Great write up, V-dog! I can’t wait to actual tackle minor key!

Dutch lives for minor chords. Now Dutch understands why a bit better thanks to VDog. Nom-nom-nom…. 🙂