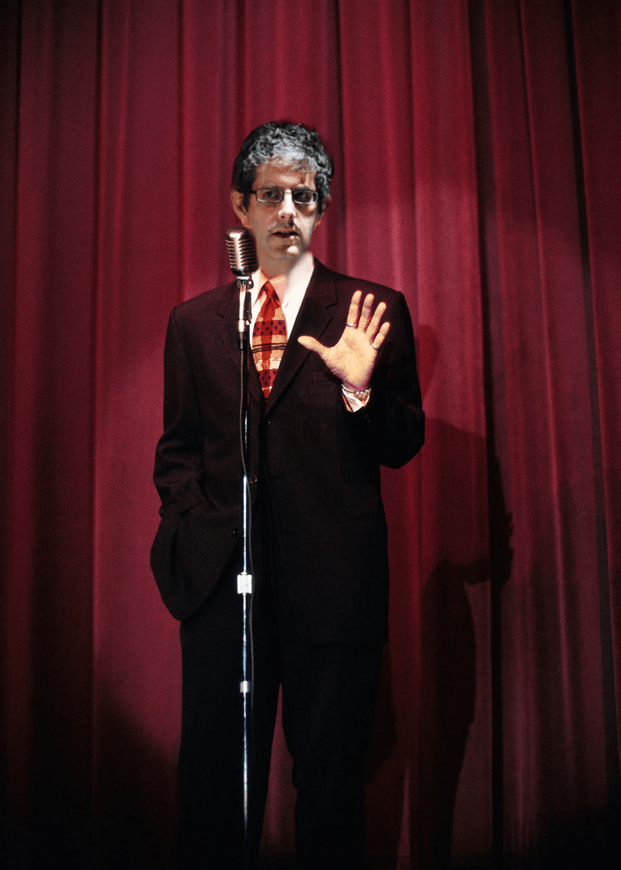

Bill Bois’ Music Theory For Non-Musicians™

…if there was ever an art where breaking the rules is one of the rules, it’s music.

redditor u/COMPRIMENS

S2:E8 – What Makes Electronic Music, Electronic Music ?

All musical instruments fall into one of these five families: percussion, brass, woodwinds, strings, or keyboards.

Then we found a way to make music without any of them after Ben Franklin flew a kite in a lightning storm.

Electricity makes it possible to light our homes, run huge machines, blow dry our hair, power the device you’re reading this column on, and make some wicked cool noises. Zzzzt. Neeee-koooww. Blurp.

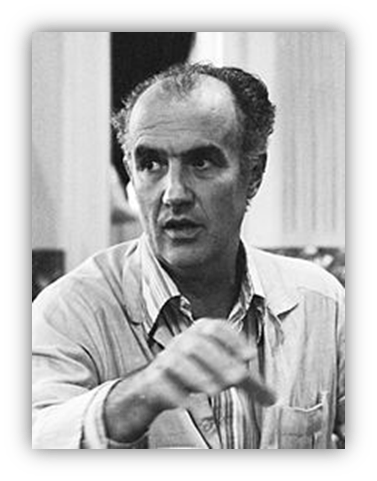

In the late 1940s, Pierre Schaffer worked at Radio France as an engineer.

He had full access to the sound effects department. He would copy sounds – locomotives, bike horns, gongs – onto single groove lacquer disks so the sounds would repeat ad infinitum. He was interested in separating the sound from whatever created it so he could study it on his own.

By layering these sounds on top of each other, he created musique concrète, which we define as music created by recording, editing and altering found sounds. Schaffer went on to a more illustrious career as a linguist, author, and theorist, and toward the end of his life he dismissed musique concrète and his entire musical output. He preferred Bach, Beethoven, and other traditional composers.

But some musicians and academics liked musique concrète and developed it further. France became the center of the movement and The Groupe de Recherches Musicales, where Schaffer was once administrator, still works to expand what we consider music.

Composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage put aside the instruments, at least temporarily, and worked with tape machines and found sounds. Stockahusen was the first to compose a piece with the intent to use only electronics to realize it. Other composers, like Luigi Nono, incorporated electronics into their works with the traditional instruments.

Some of the ways recorded sounds can be altered include adding echo, playing the tapes at different speeds, and putting the tape on the machine backwards. You can cut the tape with a razor blade and use just a portion of the sound, and then alter and repeat that much. This is how you can make music with sounds that don’t exist in nature, or come from instruments. It’s called tape manipulation.

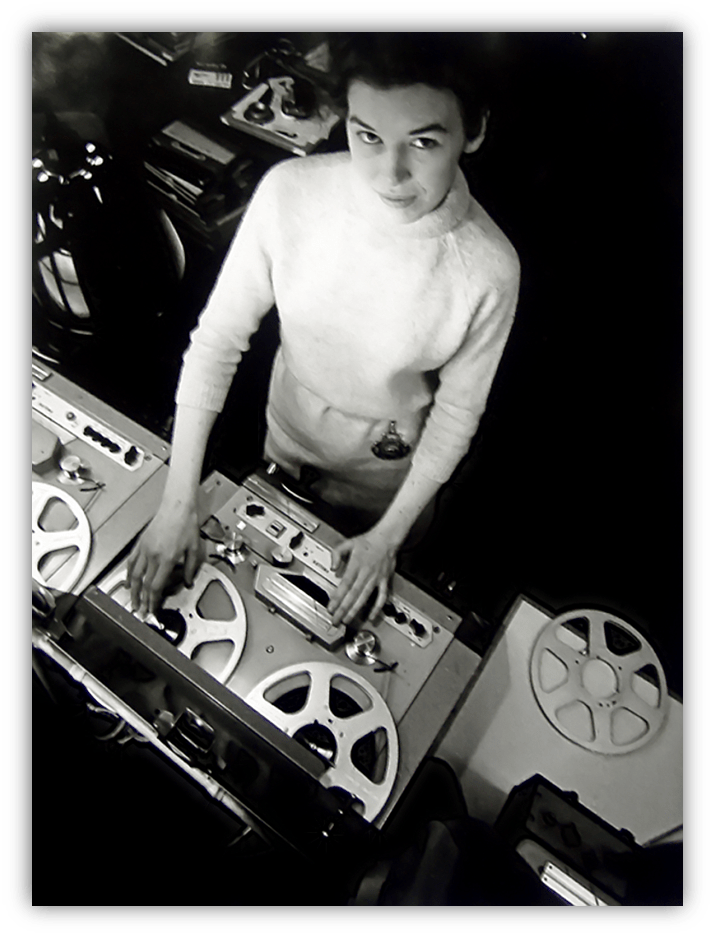

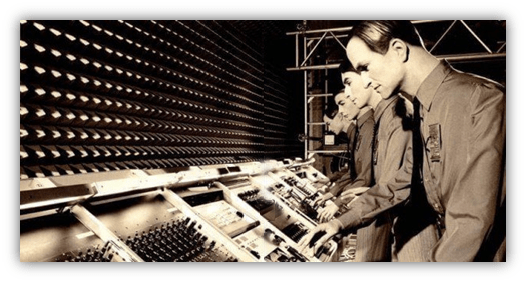

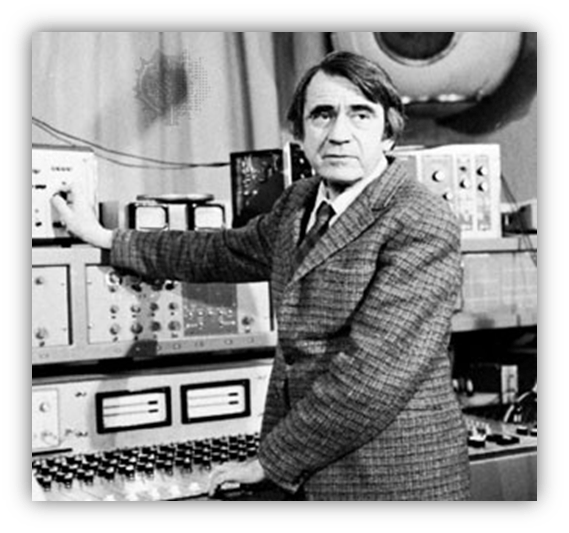

Tape manipulation was big over at the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop, the department tasked with creating sounds and sound effects.

The Workshop used some of their budget, sort of against the BBC’s wishes, to buy cheap, obsolete reel-to-reel tape machines. They’d fiddle with the electronics until they made sounds they weren’t designed to make.

In 1963, Ron Grainer composed the theme song for a new TV show. Since it was science fiction, he wanted something edgier than traditional instruments. So he went to the Workshop and gave his handwritten, one-page score to Delia Derbyshire, one of the technicians.

The score was carefully worked out but contained instructions like “sweeps” and “wind bubbles.” It was up to Derbyshire to turn it into audio.

Derbyshire had degrees in mathematics and music, and is the only musician I know of who designed music with a slide rule.

She did that because she needed to work out how fast a tape had to play to make a particular pitch, and how many centimeters it needed to be to last as many milliseconds as it had to.

She created three separate tapes, each made up of multiple sounds bounced from tape machine to tape machine and spliced together with cellophane tape. One tape was the bass sounds, the second was the high pitched melody, and the third was what she called “details,” the swooping sound effects you hear throughout. With the help of Dick Mills, she played the sound of these three tapes playing simultaneously and recorded them onto a fourth machine.

And, voila:

The Dr. Who theme song. Remember, there are no real instruments in this:

Granier was so impressed with Derbyshire’s realization that he wanted to give her part of the royalties. She wasn’t allowed to accept them, however. As a BBC employee, she could take no payment or credit outside of her salary.

While musique concrète was an intellectual exercise and Derbyshire’s work was utilitarian (though done with love and enthusiasm), each excited musicians about the possibility of music made without instruments.

At some point, people started combining tapes with instruments.

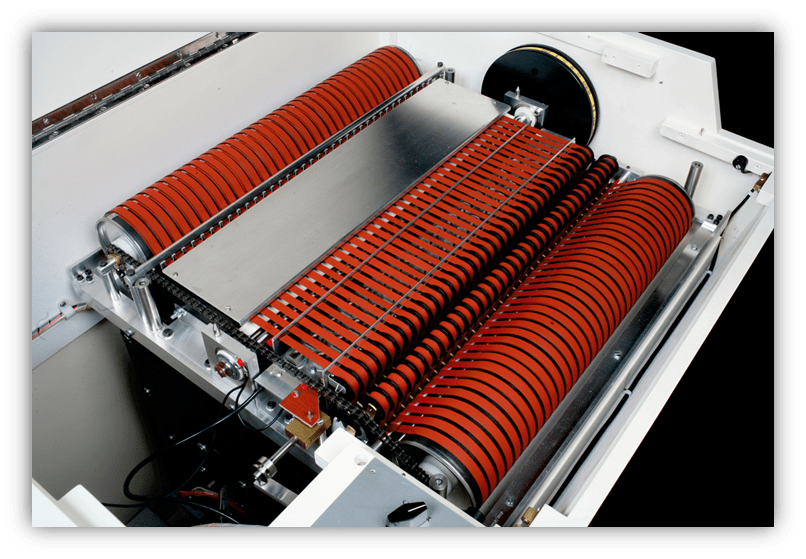

In the late 1940s, Californian Harry Chamberlin invented and produced a series of keyboard instruments that played tapes. They were the precursor to the more popular Mellotron.

The Mellotron had strips of tape on which were recordings of real instruments.

Let’s say the instrument was a trumpet. A trumpet player was hired to play every note on the keyboard for a couple seconds. The tape was then cut up so each pitch was on its own two or three foot length of tape, and these tapes were installed into the keyboard console. When a key was pressed, a weight pulled the tape across a tape head and the recording of that note was output to an amplifier.

It’s a brilliant idea, but there were a few problems. Notes could only be held as long as the length of the tape. That note couldn’t be played again immediately because a spring had to pull the tape back to its original position. Tapes stretch and wear out. And it was hard to move these machines without knocking the tapes out of alignment.

Still, they were amazing for the time.

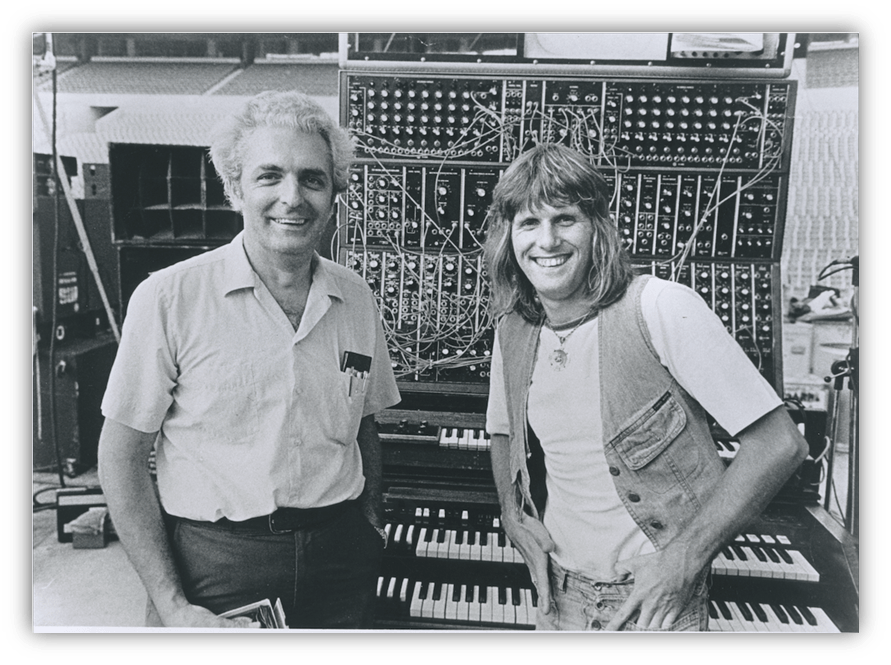

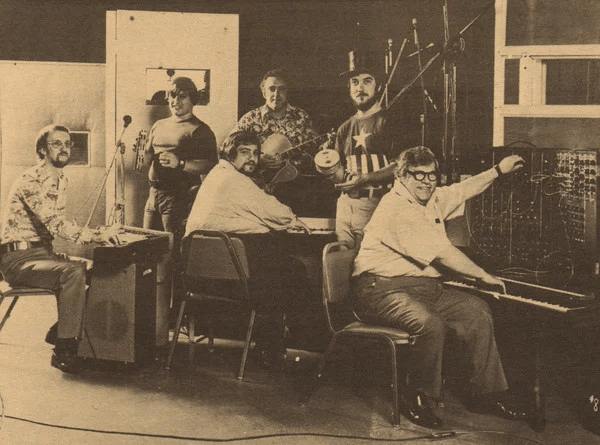

Years later, Bob Moog developed a keyboard that would control how much voltage was fed to an oscillator, and it would create different pitches depending on the voltage.

You could also adjust the shape of the sound wave the oscillator made, thus creating different timbres. This was the first real synthesizer.

At the beginning, I think that everybody outside of the electronic music field thought that synthesizers were supposed to imitate traditional instruments.

Whereas the people who were inside electronic music wanted to use synthesizers to make completely new sounds.

Robert Moog

Next time you’re in Asheville, NC, take the tour at Moog Music. It’s interesting and they let you play with the instruments.

Novel recordings, like The Well Tempered Synthesizer on which Wendy Carlos played Bach, sold well but were pooh-poohed by other musicians, especially in Germany, who were trying to create something new. They saw going back to Bach as a step backwards.

Or Bachwards, if you will…

“And be sure to try the fish.”

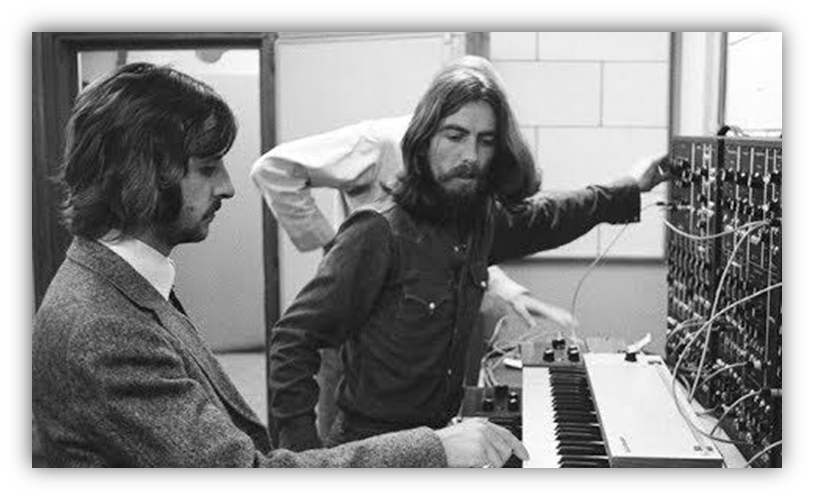

I mention The Beatles a lot in this series, but they were tuned into the electronic music scene. So I’ll mention them again. Not only did they use tape manipulation on Tomorrow Never Knows in 1966, they used an early Moog synthesizer on four different songs on their 1970 album, Abbey Road.

In all those cases, and in the cases of other popular bands at the time, the use of electronic instruments was secondary to the real instruments.

There were, however, rock bands that featured electronics as the main instruments.

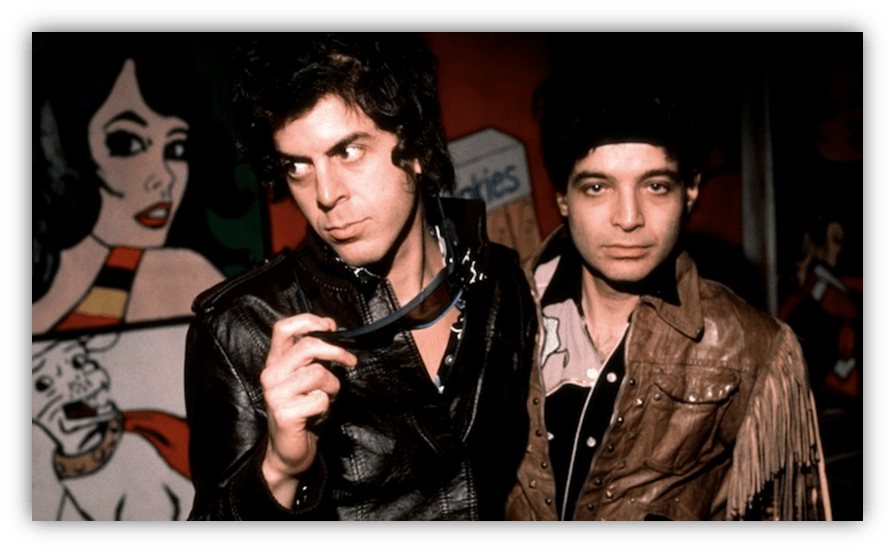

In New York City, a duo called Silver Apples consisted of only vocals, drums and a homemade synthesizer. They were just starting to get popular (At the mayor’s request, they played for 10,000 people in Central Park on the night of Neil Armstrong’s first walk on the moon.) when a controversial album cover ended their career.

However, they influenced many other bands including Suicide, another NYC electronic duo who in turn were hugely influential on the punk and new wave scenes towards the end of the 70s. Bootlegs of the two Silver Apples albums were also very popular with musicians in Germany.

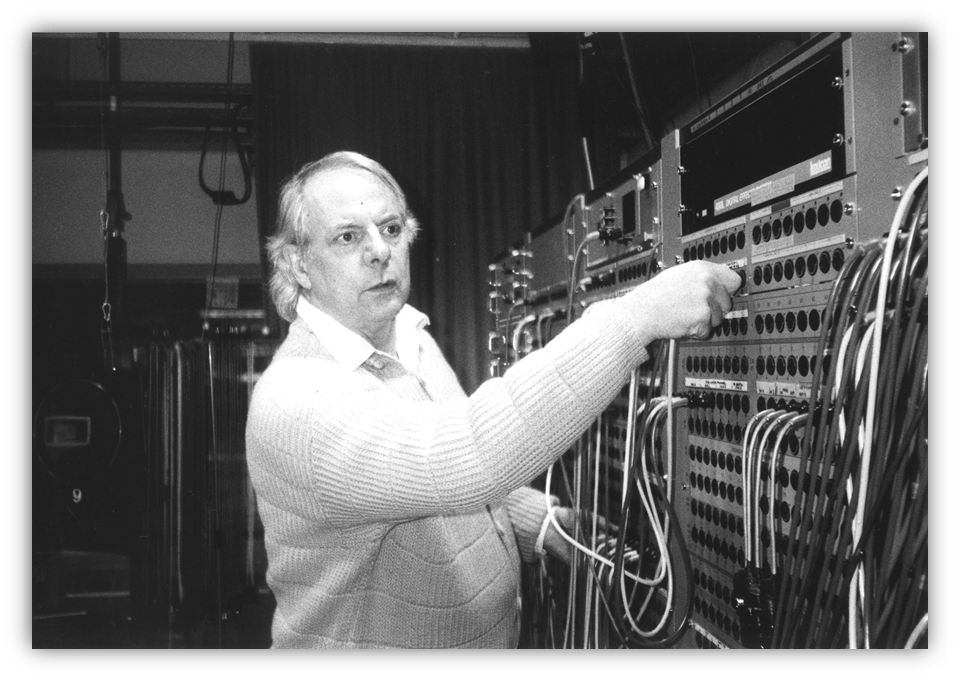

Over in Düsseldorf, Kraftwerk started as a somewhat ordinary prog rock band, but went fully electronic by their fourth album.

They used Minimoogs and other commercially available synthesizers, and also made their own instruments, notably synthesized percussion.

Their 1974 single “Autobahn” made it to #25 in the US, #11 in the UK, and #9 in Germany.

Record producer Giorgio Moroder was Italian by birth but lived in Germany. In 1977, he was working with singer Donna Summer on her album I Remember Yesterday. It was a concept album where every song was supposed to represent a different decade. They wanted the last track to sound like the future.

Composer Eberhard Schoener loaned Moroder a synthesizer and Schoener’s assistant, Robby Wedel, showed him how to synchronize tracks to a click and helped with the song’s recording. The only real instrument in the song I Feel Love is the bass drum. It went to #6 in the US and #1 in seven other countries.

As popular culture embraced these sounds, demand for electronic instruments grew and manufacturers worked hard to produce reliable, innovative instruments.

Some of these were designed to sound like traditional instruments. Progress was swift but most didn’t succeed, and therefore became obsolete swiftly, too.

Gear that had been expensive only months before showed up on the used market. They were now affordable for young musicians who weren’t necessarily interested in sounding like real instruments. They wanted new sounds, and these cheap keyboards with their chintzy imitations of strings and drums were a good starting point.

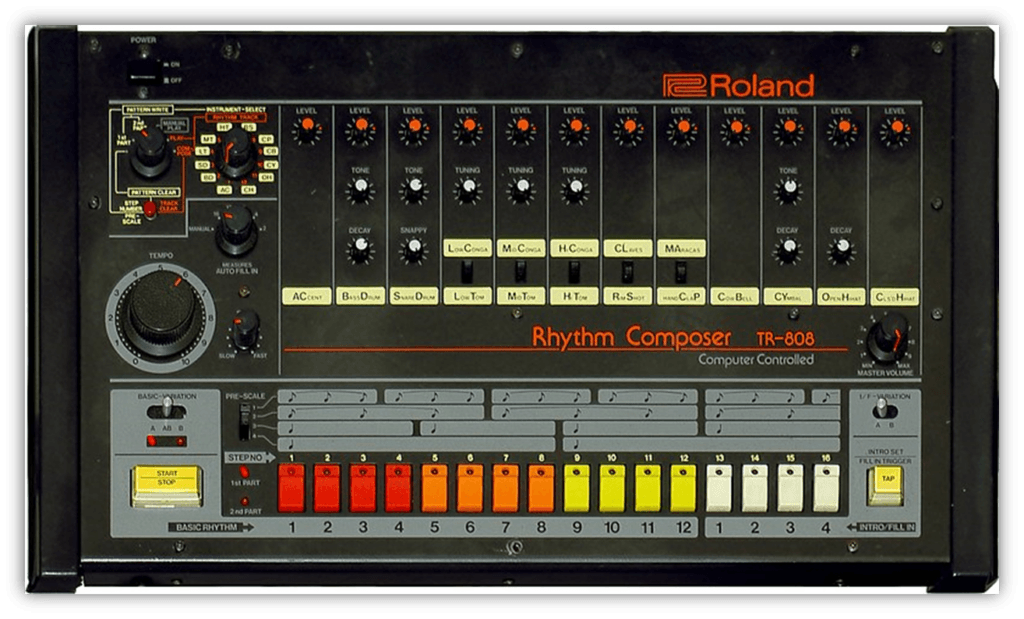

The Roland TR-808 drum machine didn’t really sound like drums, but its deep bass drum was integral to early hip hop and electronic music.

You can hear it in the 1982 classic Planet Rock by Afrika Bambaataa & The Soulsonic Force. Planet Rock also contains a sample of Kraftwerk’s song Trans Europe Express from five years earlier.

Dedicated sampling machines could store snippets of sounds and other songs and then play them back at a push of a button. Software can alter the samples willy nilly. It’s like tape manipulation but easier, faster, and better.

Speaking of software, recording wouldn’t be where it is today without the personal computer and the DAW (digital audio workstation). DAWs like ProTools and Nuendo replace large mixing consoles and all the physical equipment involved. Rather than buying a dedicated echo machine, for instance, you can just download some software to do the same thing.

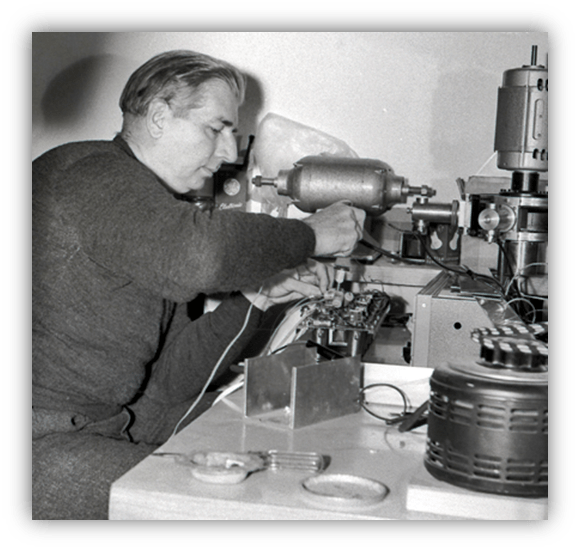

In 1955, Hugh le Caine recorded a single drop of water falling into a bucket. He then re-recorded it at various speeds producing various pitches. Using a razor blade and cellophane tape, he edited it into a piece of music called “Dripsody.” This painstaking work took hours and the final piece lasts only a minute and a half.

Today you can have software do it for you.

Likewise, you don’t need to be able to play any instrument.

You can click your mouse on the note you want played and specify its duration, volume and timbre. Want your melody played on a flute? Download one. Don’t like it? Use synthesizer software to create the sound you want.

This ease of use means anyone with a computer can make and release music.

Any moron, like yours truly, can release music without having played any instruments.

It also means that anyone can create their own subgenre. The Wikipedia page listing electronic music genres has 25 major headings, each with numerous subheadings. There are far too many to go into here: chillwave, jungle, dreampunk, chiptune, dozens of others.

Maybe we’ll get into some in future editions, but we’ll have to leave it here today.

In the meantime, here are 120 subgenres in 20 minutes.

Suggested Listening:

Cinq etudes de bruits – Etude aux tourniquets

– Pierre Schaeffer

(1948)

Dripsody

– Hugh Le Caine

(1948)

Telemusik

– Karlheinz Stockhausen

(1966)

Oscillations

– Silver Apples

(1968)

Popcorn

– Hot Butter

(1972)

Meditation Scene (from the Fantastic Planet soundtrack)

– Alain Goraguer

(1973)

Europe Endless

– Kraftwerk

(1977)

Ghost Rider

– Suicide

(1977)

I Feel Love

– Donna Summer

(1977)

Planet Rock

– Afrika Bambaataa & The Soulsonic Force

(1982)

Rhythm In The Pews

– Ray Lynch

(1984)

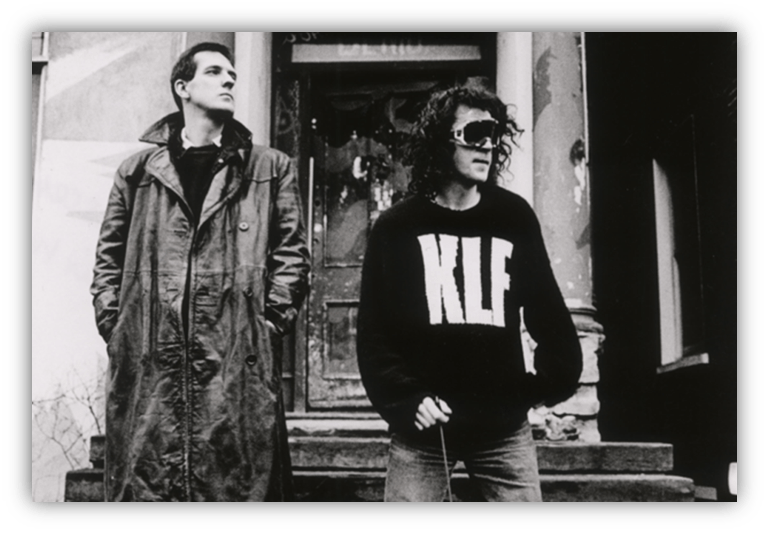

Last Train To Trancentral

– The KLF

(1991)

Midnight In A Perfect World

– DJ Shadow

(1996)

The Box

– Orbital

(1996)

The Sunshine Underground

– The Chemical Brothers

(1999)

Flight 643

– DJ Tiësto

(2001)

Slow Percolator

– Bill Bois

(2007)

(Let the author know that your liked their article with a “Heart Upvote!”)

Another great entry! This topic gets to the heart of why I started out my music blog in the first place. I was getting into all of these early electronic artists and trying to understand the heritage and history.

A few points of nerdy clarification:

Composers had incorporated electronic instruments in their work since at least 1934 (e.g., Varese’s Ecuatorial used theramin).

The first all-electronic work was arguably Olivier Messiaen’s 1937 “Fete De Belles Eaux” for six Ondes Martenots.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nrYgm5MML58

The first electro-acoustic performance piece was John Cage’s Imaginary Landscape No. 1 in 1939.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GwY2gO-5Uw8

The first electro-acoustic manipulation of recorded sound was actually done a few years before Pierre Schaeffer, by Halim El-Dabh in Egypt 1944. Schaeffer discovered the technique independently, mastered and refined it, and gave it the name “musique concrete.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j_kbNSdRvgo

The first synthesized electronic music came from Herbert Eimer in 1952 (who incidentally hated musique concrete):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BLSZ3cTI-6Y

The first electronic music sequencer was invented around 1954 by Looney Tunes-fame genius Raymond Scott. Scott was a mentor for a young Robert Moog, who worked in his lab before coming up with his own creations.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5A052VLTZ_I

Oh, and the first “industrial noise” music was made in 1913 by proto-fascist Luigi Russolo!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IC3KMbSkYNI

Goodness! I stand corrected and will go down these rabbit holes. Thanks for all of this!

BTW, where do we find your blog?

Here’s the link:

https://phylogenicrecords.wordpress.com/

(I haven’t published in a bit; still working on how to organize and divvy up the 60’s material)

Fabulous work. We are so fortunate that you publish at our site.

Aw, shucks. ‘T’weren’t nuthin’.

Unsurprisingly, given the nature of Doctor Who fans, the Doctor Who theme may be one of the most intimately dissected pieces of music outside of the Classical canon.

Here’s a website that lovingly takes it apart and puts it back together:

https://www.dwtheme.com/

Wow, now that’s fascinating. Thanks, Eric!

Fantastic stuff! Delighted to see Delia get her due, can’t imagine how freaky the Dr Who theme must have sounded in the early 60s when the average TV viewer will have heard nothing like it. Dripsody is quite something too, sounds like an early arcade game gone hyperactive. There’s often a disparagement of electronics that its not real music or they aren’t real musicians but the range of sounds and inventiveness that the ever evolving technology allows is a wonderful thing to me.