Music Theory For Non-Musicians

…if there was ever an art where breaking the rules is one of the rules, it’s music.

redditor u/COMPRIMENS

This occasional series is about how music is made, and it’s for people who don’t already make music. It’s part music appreciation and part music theory.

I hope to cover rhythm, melody, intervals, chords, inversions, genres, and more. Maybe we’ll get into extended chords and modes. Let’s see!

S2 | E3 – What Makes Jazz, Jazz ?

Jazz is music for musicians.

Really, that’s it.

I could end this article here, but it probably warrants a little more explanation.

If we want to go way back, jazz started after the Civil War in New Orleans. Recently freed black people still worked long hours six days a week. They’d go to church on Sunday mornings and some would then go to the open market in Congo Square in the afternoons to play music together. Much of that music was improvised. Congo Square is considered to be the birthplace of jazz.

Others say that jazz started with ragtime piano, which I’ll get to, but I’d argue that jazz didn’t really become jazz until the invention of the drum set. Prior to that, percussion wasn’t handled by one person. Some people played snare drums, others played tom toms, a few had cymbals and tambourines. One would play the bass drum. That all changed with the bass drum pedal.

The bass drum pedal allowed musicians to play the bass drum with a foot (which is why it’s now also called the kick drum) and have their hands free to play other instruments. That could be a guitar or trumpet or something, but it could also be other drums.

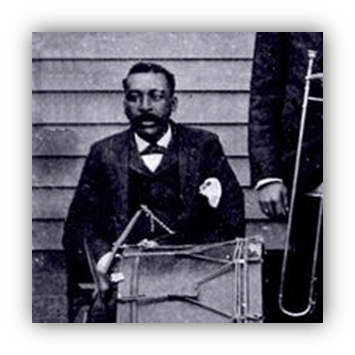

There’s some argument about who invented the bass drum pedal, and patents for various designs go back to 1850, but the drum set itself is thought to have been invented by Edward “Dee Dee” Chandler in New Orleans in the mid-1890s.

He made his own bass pedal out of a steel spring, a chain, and wood from a milk crate, and then tied a snare drum to the bass drum with rope. It wasn’t much, but he was an immediate hit and other drummers started putting together their own sets.

When a group of drummers play a single drum each, their parts must be fairly rigid and predictable. Each player has to play right on the beat and stay in sync with all the others. Once the drum set came along, a single drummer could experiment with playing different parts with his various hands and feet.

He, and it was almost always he, could play a straight beat on the kick drum, for instance, and triplets on the ride cymbal. He could leave notes out. He might be slightly late on some beats. It might be late by only milliseconds, but playing “behind the beat” or even “ahead of the beat” makes the music more lively. More danceable.

There are endless variations that are easier for one person to come up with, or improvise, than for an entire drum section of a band. Ragtime piano players had been experimenting with syncopated rhythms for a while. It’s subtle but you can hear it in this piano roll of Grizzly Rag that George Botsford recorded in 1910. There’s nothing stiff or regimented about it like there would be with a drum section.

That kind of loose rhythm ragtime solo artists were using could now be done by an ensemble with a single drummer giving them a swinging beat. This is why this syncopation is called swing, and swing is a crucial element of jazz. There is, in fact, an entire subgenre called swing. Here’s a quick video explaining the elements of swing.

The key word here is “experiment.” Ragtime players tried something new, and they came up with beats that swing, and then drummers with the newfangled drum set tried it, too. Experimentation – the pushing of boundaries, exploring new sounds and rhythms and harmonies and structure – is what I mean when I say “jazz is music for musicians.”

Jazz is musicians pushing the art and themselves and each other as far as they can go.

Now, sometimes that makes the music unlistenable for some non-musicians. But some of the most popular songs of the first sixty years of recorded music are classified as jazz. With its swinging rhythms, it was primarily dance music.

In the 1940s, the United States had a war to pay for. To help with that effort, the federal government instituted a 30% Cabaret Tax.

It was an excise tax on any establishment that served food or drink and had live music for dancing.

A few nightclubs got around this by hiring performers to lip sync to records. Since no one was singing or playing instruments, it didn’t meet the legal definition of cabaret, and audiences still got to see performers in elaborate costumes.

Other venues replaced the dance floor with tables and chairs. If there was no dancing, they didn’t meet the definition of cabaret either. Not only did this save the club all that tax, there were more seats to put customers in. For the musicians, it meant they were no longer limited to playing just dance music. They could experiment more.

The chief result was bebop. This major subgenre of jazz was sometimes too fast for dancing because musicians were free to see how fast they could go. They played parts of astounding complexity at lightning speeds, and an awful lot of it was improvised, made up on the spot.

Here’s John Coltrane making it up as he goes on a 1959 tune called Giant Steps. It’s the one jazz sax players aspire to, both because of the speed and the complexity of the chord pattern he’s playing over. In this video, someone has transcribed his improvised solo.

The structure for bebop and other jazz songs is head / solos / head. The head is a recognizable melody that’s played at the start and end of each tune. The chord structure under that melody is then repeated as the various players take turns improvising solos over it. Each solo might be twice through the chord pattern, but if a player is having a particularly good night, he might solo through it three or four or twenty-seven times.

Every night is different, which is why live jazz recordings always have the venue and date listed on the cover.

The other thing you’ll find on every cover is a list of the personnel. Like authors, the best musicians have their own voice. Chet Baker and Maynard Fergurson both play trumpet, but sound nothing alike. Dedicated jazz fans can look at the personnel – this piano player with that bass player and those two horn players – and tell whether they’ll like a record or not.

In addition to speed, another common characteristic of bebop and all jazz is extended chords.

In last week’s article about country music, I talked a bit about the 7th chord. To make this explanation as easy as possible, let’s start with a major chord.

The C major chord is made up of three notes, C, E, and G. Notice that it skips over the notes D and F. (The technical explanation is that the notes are a third apart, but let’s keep this simple.)

If we keep using that pattern to add more notes, we’ll skip over the A and add a B, which is the 7th note in the C major scale: C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C. So this new chord made up of C, E, G, and B is called C major 7.

Let’s extend it further and say the scale is two octaves: C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C. From that B we just added in the C major 7 chord, we’ll skip over the next note, which is C, and add the D. So now we have C, E, G, B, and D. It’s called a C major 9. We call it a 9 to specify we want the second D up from our root note.

And if we keep going, we’d skip the E, add the F to use C, E, G, B, D, and F, and we’d have a C major 11 chord.

These extended chords can get as complicated as you want. You can add another note up for a 13 chord. You can flatten, say, the 7 or sharpen some other note. You can put any of these notes in the bass part. Some extended chords are beautiful. Others, not so much, but this is why jazz musicians must understand music theory inside and out.

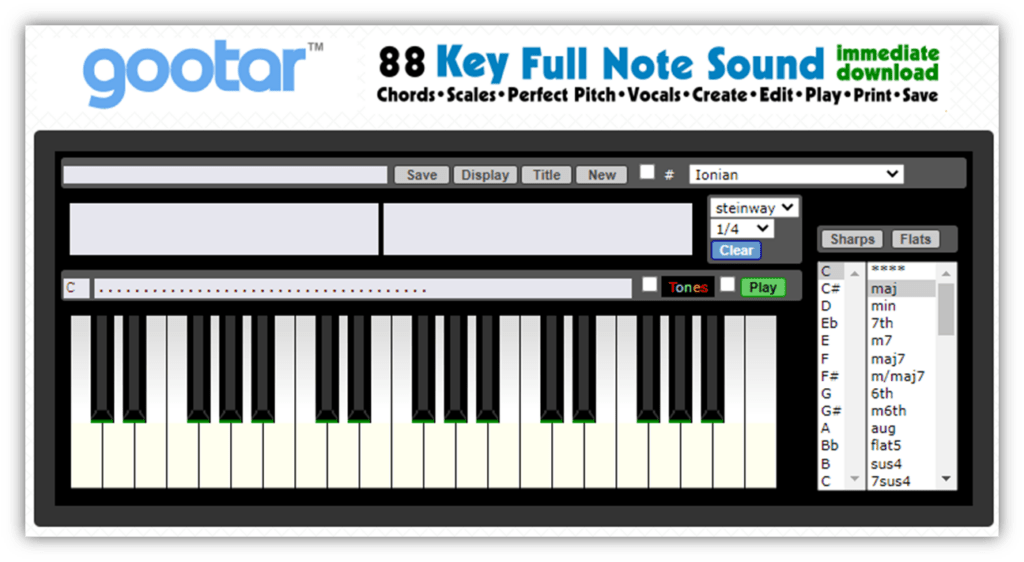

If you want to have a little fun, go to http://www.gootar.com/piano/index5.php and start clicking notes on the keyboard. You can select notes on a pseudo piano keyboard and the site will tell you the name of the chord.

In this very abbreviated history of jazz, the next big change was fusion.

This was the joining of jazz musicianship with rock intensity and instruments. The synthesizer became an important instrument.

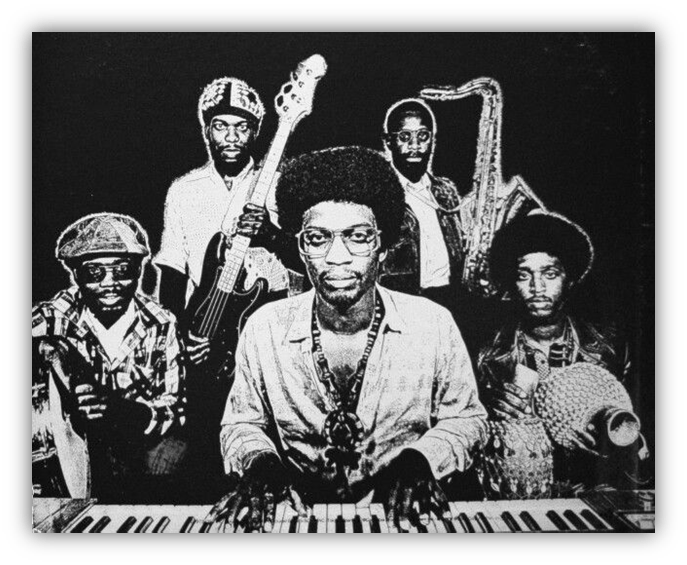

1973 was a big year for fusion with album releases like Return To Forever’s Light As A Feather, Herbie Hancock’s Headhunters, and Billy Cobham’s Spectrum. While fusion attracted jazz players, a lot of rock musicians joined in. Jeff Beck, Carlos Santana, and Phil Collins were part of the fusion scene.

The 1980s brought smooth jazz, a sort of mellowed out, vocalless R&B with excellent musicianship. Many in the jazz community saw it as a money grab by artists and labels, and that it was a step backwards. While it’s true that smooth jazz didn’t have much experimentation, there’s no denying the talent of players like Chuck Mangione, George Benson, and Kenny G.

It’s hard to say where jazz is going in the 21st century. Part of that is my own lack of knowledge.

To my ears, jazz in 2022 sounds more influenced by bebop than by anything since. Throw in some contemporary classical, too.

The other part of predicting where jazz will go is the great jazz experiment will take us where musicians yet to be born take it.

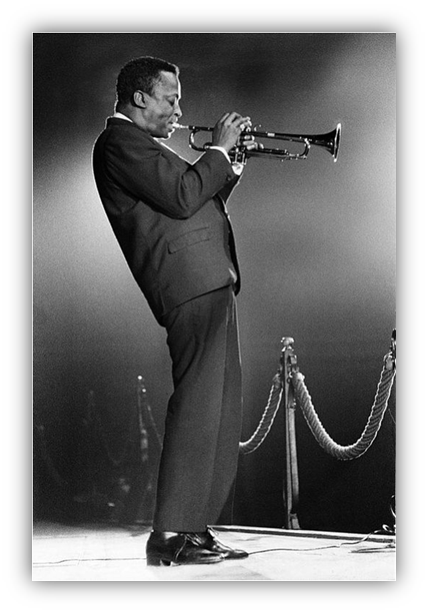

The next Miles Davis could still be in diapers. Hang on, this could swing hard.

Suggested Listening

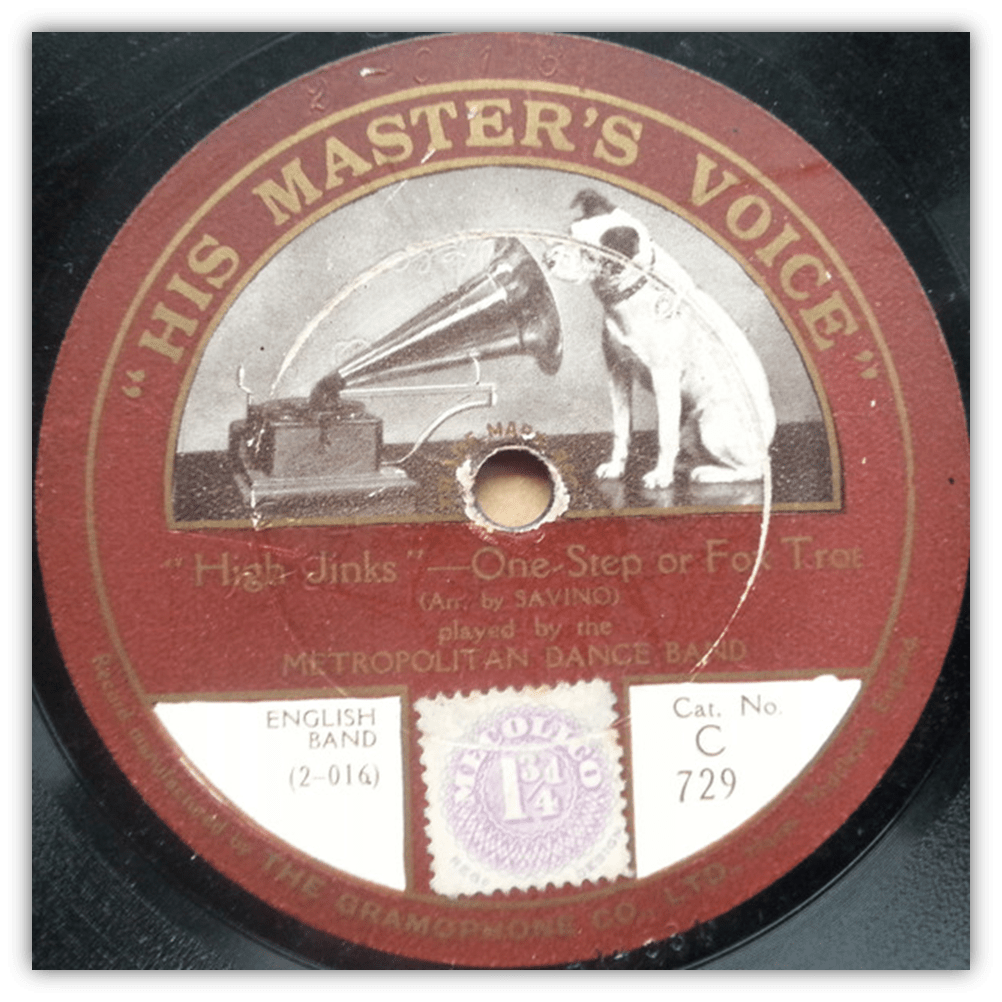

Metropolitan Dance Band – Music Box Rag (1914)

Mildred Bailey – Rocking Chair (1932)

Tommy Dorsey – Boogie Woogie (1938)

Miles Davis & Charlie Parker – A Night In Tunisia (1946)

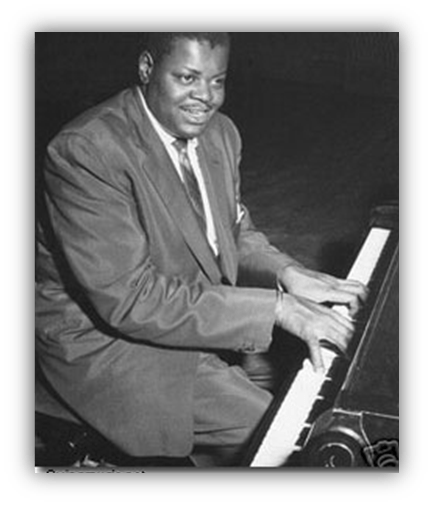

Oscar Peterson – Smiles (1947)

Miles Davis – Move (1957)

Les McCann & Eddie Harris – Compared To What (1969)

Herbie Hancock and the Headhunters – Chameleon (1973)

Weather Report – Birdland (1977)

Spyro Gyra – Cafe Amore (1980)

Kamasi Washington – Final Thought (2015)

(Let the author know that your liked their article with a “Heart Upvote!”)

Paraphrasing Louis Armstrong, “If you have to ask, you’ll never know“

One of my favorite quotes of all time!

And a good welcome to you, @Che Boludo !

Thanks so much for the welcome @mt58

Something else popped into my head that seemed appropriate, Many years ago, I was asleep in my college dorm room when the local university station woke me up with some spoken word type beatnik poetry about how “Kenny G is not jazz, jazz is not Kenny G” It has always stuck with me and is also a great way to define what is and is not jazz. I can’t find the damn track on youtube though.

I found it (I think). I thought it was a much longer song repeating again and again how Kenny G. is not Jazz, Jazz is not Kenny G. This is what I found.

This Train – The Emperor’s New Band – 06 – Jazz

Don’t be deceived by the false prophets of jazz.

Heh! That’s awesome. Miles Davis is the Elvis of jazz.

I suspect Miles Davis would not be a fan of Elvis.

I did find this Googling to see if there is any record of Elvis and Davis crossing paths, no, not from what I can tell.

Miles Davis and Elvis Presley: The Political Potential and Social Threat of Iconic Outsiders

Elvis is the iconic rural Southerner and Social Escapism while Miles Davis is the iconic Black Public Figure Political Alternative. Hmmm, the Author associates Davis with they Free Jazz movement.

Years ago I was studying at home with some Beethoven playing in the background. At one point I was yanked from my reading by what suddenly sounded like jaunty saloon music. From Beethoven? This was my introduction to his 32nd Piano Sonata, which has some prominent syncopation in its middle section:

https://youtu.be/ccyHT1sFmsg?t=1031

It’s cool that Beethoven got so close to the spirit of ragtime back from 1822 Austria. But still, there is a crucial element that separate his loose and “ragged time” from real ragtime: it’s not attached to any danceable rhythm.

Ragtime ties its light and loose top melodies to a driving bass rhythm, probably taken from marching band music. Early jazz was also deeply indebted to military march and funeral bands, and also respected the need for a steadfast rhythm section to anchor its freewheeling elements.

That relationship to steady, danceable rhythms changed over time, as you mentioned, and jazz musicians sought to be more than mere entertainers. The desire to be regarded as important modern artists compelled many to challenge themselves and their audiences–with the result being that “America’s music” started to turn more and more into a niche movement rather than a national sensation.

By the 1980s, the identity crisis of jazz had reached its peak, and this was perfectly represented by the feud between Miles Davis and the young upstart trumpeter Wynton Marsalis. Marsalis argued that whatever Miles was doing–including playing with Prince–wasn’t jazz; it was just desperate trend hopping. And yet Davis argued that Marsalis preferred “wax museum” imitations of classic innovators rather than tap into the true restless spirit of jazz.

Who was right? Well, both, and neither. As much as I tend to sympathize more with Davis’ more forward-looking artistry than the traditionalism of Marsalis,’ I think a big part of what made traditionalism so appealing was its social dimension. Marsalis pined for the time when elite Black musicians like Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong could make music that could draw an entire nation in, could bring community members closer together, and could supply kids everywhere with heroes they could aspire to become.

Jazz as avant-garde or as pop fusion simply couldn’t fill those social roles, and so he looked back to the golden age for his model.

Anyway, for those who haven’t seen it, Ken Burns’ “Jazz” documentary mini-series is an excellent intro course into the history and evolution of jazz. Marsalis is one of the producers, and his talking head is all over the series, so it’s without a doubt very heavy on a traditionalist point of view. But that makes sense for the series, because it’s mostly about jazz as the music of America. He covers the avant-garde and fusion eras much more briefly, because by the 1960’s, most of America had moved on to other things:

“I’ve have no kick against modern jazz

Unless they try to play it too darn fast

And change the beauty of the melody

Until they sound just like a symphony

That’s why I go for that

Rock and roll music

Any old way you choose it

It’s got a back beat, you can’t lose it

Any old time you use it

It’s gotta be rock and roll music

If you want to dance with me”

I don’t think I’ve heard Beethoven’s 32nd before and it’s way cool. He was always hip.

The whole Davis/Marsalis feud was disappointing. Marsalis came across as a jerk, which is too bad because he’s a good educator. We all have our ups and downs, I guess.

Yeah, for sure. Certainly Miles Davis was infamous for his downs. He could be difficult to work with, and a terror to live with.

Excellent as ever. Enjoyed the history lesson showing the evolution of the genre.

I’m afraid when it comes to Jazz the regular Jazz Club sketch on The Fast Show is my main touching point;

https://youtu.be/MsQYzpOHpik

Greeaat.

Suits you, sir.

Nearly forgot to mention, mt58 had to take goodboy to the airport today. It seems goodboy is auditioning to be one of the new king’s trademark dogs now that the corgi’s have abdicated their positions. Good luck, goodboy! We know you can do it.

Anyway, mt58 is tied up and won’t be posting The Weekend Files today. If he were here, I know he’d say it was a fun week here on tnocs.com, have a good weekend, and good on you all.

Kind of Blue made me want to listen to more jazz, not more avant-garde or uncategorizable music.

What I remember most about Miles Davis was his appearance on The Arsenio Hall Show. The sound of sneakers hitting the hardwood of a basketball floor was jazz, Davis told the host.

Bitches Brew is pretty awesome, though.

KoB introduced me to jazz like so many others and decades later it is still a top 5 personal favorite and I’m pretty sure an objectively perfect album. I played around with the avant-garde stuff learning about jazz, the later Coltrane, later Miles Davis and that stuff just never took.

II always have to give a shout out to another top 5 personal favorite and the closest jazz vibe I’ve found to KoB, Idle Moments from Grant Green. The only thing stopping IM from being objectively 100% perfect is that the albums vibe is almost entirely mellow and moody until Nomad closes the record out in a much higher tempo, which is a fantastic cut, but just doesn’t fit the vibe of everything coming before it.

I’ll have to give Idle Moments a listen. What do you think of Coltrane’s A Love Supreme? To me, that’s a perfect album, but it is a lot more passionate and intense than Kind of Blue (though still nowhere near as outré as later stuff like Ascension and Om).

Avant-garde Coltrane for me is like a religious rite, like a shamanic journey that I have to take sometimes, if rarely.

Miles’ later stuff though is really, really dark. Even his funk fusion stuff just sounds bleak, despite the ostensibly fun trappings. I’m certainly gonna write about that in my blog about industrial music.

I like A Love Supreme but ultimately comes down to the fact that I’m just not crazy about Coltrane. Honestly though, I dislike later Coltrane and I’ll take Giant Steps over ALS. I’m much more into bluesy players. I love Stanley Turrentine, Dexter Gordon and the like as far as hard bop goes but I also like some of the more swingin’ Verve stuff like Oscar Peterson and the like. You could say my tastes run toward the relative pedestrian side of jazz, just not Kenny G. I like Cannonball on KoB more than Coltrane, but still 100% perfect album.

Touching back on the trumpet, far more than Davis, Clifford Brown is my main man, he did some great work with Sonny Rollins though too. Backpedaling a little bit, getting outside of more traditional sax players, Rolllins is where I’ll go a little, avante garde is not the right term, but wierd. Rollins is a little odd.

I think I completely get what you mean by later Miles Davis being dark, but what is really curious to me is what are you going to write regarding Miles on your blog on industrial music? Obviously, you are a very musically genre-fluid person.

That makes sense. Interestingly, it initially took me a bit to really get into Kind of Blue, and it was because I found Coltrane’s presence to be a bit jarring! But he really adds to the modal fluidity of the album, and I’ve since come around to his strident style.

As for my blog, I’ve been exploring the deep ancestry of industrial music, so pretty much anything from the industrial revolution onward is fair game to cover in terms of cultural touchstones.

Even without that broad framework, though, dark urban funk from the 70s was a huge influence on a few important industrial acts like Cabaret Voltaire and 23 Skidoo, so Miles and others in that vein will get a write-up eventually (of course, I’ve just entered the 1960s, which is chock full of stuff to write about, so who knows when I get to the funk-fusion era).

Wow. Cabaret Voltaire. What would Miles Davis think of current electronic artists such as Daniel Lopatin and Arca?

Hmmm, hard to say. Miles proved himself to be astoundingly open-minded as far as new music was concerned. I don’t think he’d be against the idea of playing along to their beats, similar to what Bjork did with Arca on Vulnicura, and what Miles did with Easy Mo Bee on Doo-Bop.

It always amuses me to know that later in his career, Miles would perform (Cover?) Cyndi Lauper “Time After Time” and Michael Jackson “Human Nature“.

Those tracks are not good.

Davis is on record for saying the Beastie Boys’ album Paul’s Boutique is the best album he’d ever heard, so he was definitely not out of touch with trends…

Citation?

OK, I wasn’t sure I was understanding your definition of “industrial music” I always thought of it as bands like MInistry which isn’t exactly the case. I think I see the connection between Nine Inch Nails and Cabaret Voltaire after a very brief listen. 23 Skidoo I liked better. I could here where fusion might fit in better there.

What happens in the 60s?

I don’t know what you heard from Cabaret Voltaire, but their stuff from 82-84 shows an interest in Funk and other grooves. Here’s an example:

https://youtu.be/byExEMIrr8k

What happens in the 60s, I’m typing this from a phone at the airport, so I can’t access my notes, but just going from the top of my head: civil rights gains turning into anger and frustration by the end of the decade, loss of trust in government, avant garde movements like Fluxus and Viennese Actionism. Musically: psychedelia, early funk, LaMonte Young, Terry Riley and Steve Reich’s tape loops, Penderecki, John Cale’s early guitar drone experiments. Not to mention the slow rise of the other villain of industrial artists (aside from government): the religious right.

Did you ever get into Max Roach’s We Insist! album from 1960?

To me, this is avant-garde at its best. Yoko Ono surely had to have heard this album, particularly Abbey Lincoln’s dramatic vocal delivery.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SAzTCfZod4c

I hear it. I had the same reaction as when I heard Karen Dalton for the first time. Wow. Almost as idiosyncratic as that first Joanna Newsom album. (I miss the vocal tics.) I bought The Milk-Eyed Mender at Tower Records for three dollars on the second-to-last day. Valerie June can sometimes sounds like Newsom. And sticking with the avant-garde theme, I thought Laurie Anderson invented narration in song. And then I heard Phillip Glass’ Einstein on the Beach. And then I heard Nillson’s The Point. I think Lars Von Trier heard that one.

Dar Williams praised Yoko Ono years before the ongoing reevaluation of her work. Williams attended Wesleyan. She and her classmates thought of Double Fantasy as a Ono solo album.

Yeah, Einstein was a direct influence on “O Superman.” Though Anderson and Glass were roughly contemporaneous presences in the NYC avant-garde world–maybe it was more of a mutual cross-pollination, or channeling the zeitgeist.

I know that Ono was an early part of the Fluxus movement, but I don’t know the extent that avant-jazz figures like Roach were mingling with the Fluxus folks. At least by Ono’s first album, she had collaborated with Don Cherry, so it’s possible there was earlier cross-talk.

In my comment I just wrote about Clifford Brown I totally meant to mention Max Roach.

I know this comment wasn’t directed at me, but this doesn’t sound too avant-garde at first. It get’s a little retarded and drunken sounding and Lincoln reminds me of Nina Simone. This is still bluesy, but if we are talking about older school, bluesy and swingy, Coleman Hawkins really fits that bill.

This is really interesting and intriguing because I love Max Roach.

Wonderful! Next, get your TV show!

As always, Bill, I learn something (or multiple things) from your columns. Great job! I’d never heard about the 30% Cabaret Tax before. That’s the kind of factoid that would have captured my attention in a “recent U.S. history” class.

Loved this, VDog, it explains things so well, I find myself saying every time I read an article of yours – yeah, that makes total sense now!!

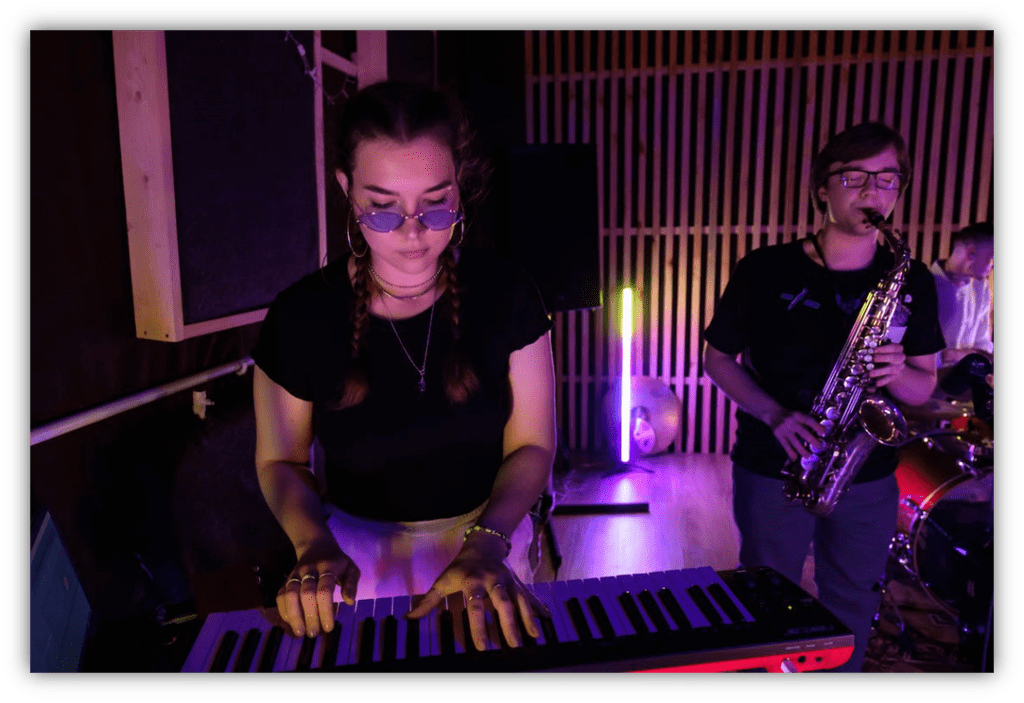

I find jazz very intimidating, because like you said, those are Musicians with a capital M. The knowledge and understanding required to stay in sync with other band members for essentially hour long jam sessions that sound effortless is mind boggling to me. But man, is it surreal.

Out of the five members of my last band, I was the only one without a music degree. I learned so much from them that I can almost talk intelligently about it here, but when the sax player started talking about playing the 2 of 5 in a solo, he lost me. I did grasp the tritone substitution eventually, which was a small victory, but yes, you’re right. How those guys run those calculations on the fly is astounding.

V-dog,

Is this the longest essay you’ve written for tnocs?

It’s great, though I haven’t had a chance yet to listen to all the examples or click on the links. Usually I don’t need to ask for an extension on the homework deadline, but…

Please?

I’ll need to read it again, and I will have questions. I have to say, though, I’d never head the Beethoven sonata below, and I found it incredibly…modern?

I’ll have questions soon enough. Thanks for doing this.