You were expecting K-Pop Part 2, weren’t you?

But after three weeks of City Pop, J-Pop, and K-Pop Part 1, I figured you’d all want a palette cleanser. I sure do.

Sorry. I’m all popped out.

So: classical music, it is.

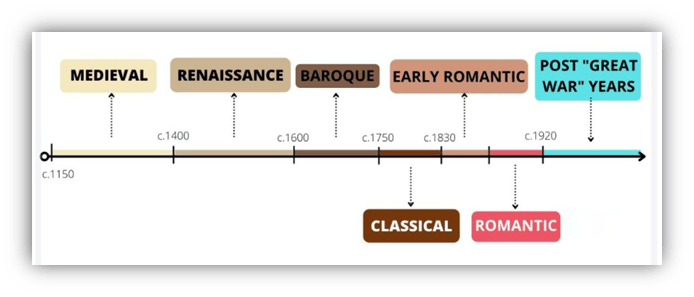

As I mentioned in the baroque article, there are six distinct periods that fall under the classical umbrella.

And one of them, the period from 1750 to about 1830, is also called “classical.”

Calling it the classical period of classical music is confusing, but this article is about the music created in that 80 year window and how it differs from the baroque period that came before and the romantic period that came after.

In 1665, a pandemic ravaged Europe.

Cambridge University was among the many institutions that temporarily closed.

One of its students took his books home to the ever so Englishly-named Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth.

Over the next two years, this heretofore average student created new ideas about optics, calculus, and gravity.

There’s no truth to the legend that Issac Newton got his ideas about gravity when an apple fell on his head. But it is true that he saw an apple fall and wondered why everything falls towards the earth rather than away from it.

Why don’t things fall, say, sideways? So an apple did indeed have something to do with it.

And in 1687 he introduced his theory of gravitation in his book Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica.

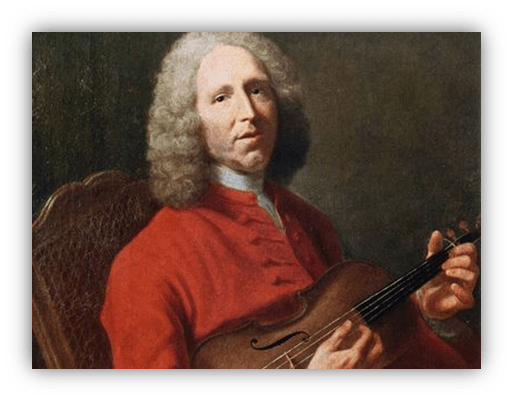

Newton’s ideas about gravity were widely known by 1722. That’s when Jean Philippe Rameau wrote Traité de l’harmonie réduite à ses principes naturels, which we just call Treatise on Harmony. Rameau says there’s gravity in music. Melodies and chords want to return to their tonal center, like the apple wants to fall to earth. He called this idea “fundamental bass.”

You know this, whether you know you know it or not.

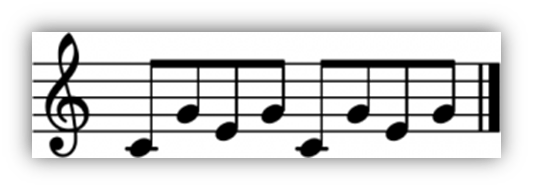

In your head, sing this:

“Twinkle, Twinkle, little star, how we wonder what you.”

Did you notice I left off the last word? Without it, you’re left hanging. You need that last note to make it feel finished. That last note is the tonic, the note that shares the same letter as the song’s key. If it’s in the key of G, it feels most complete if you end on a G.

The G is home. It’s where the falling apples want to land.

No wonder Rameau was called the “Issac Newton of Music.”

There had been books about music before but they were mostly how-to manuals. Rameau approached music as a science and a philosophy, attempting to unveil the “why” of music theory and understand the natural laws governing it.

It was the Age Of Enlightenment, after all, and people worked hard to truly understand the universe and all the things in it.

Just putting tunes together wasn’t hip. Composing should be thoughtful and follow natural laws.

Nerds were cool.

At the same time, composers were taking a back-to-basics approach.

Which was kinda punk of them.

Bach and the rest of the baroque cats had shown that you could have four melodies going at the same time and they would work in both vertical and horizontal harmony.

That’s called polyphony, and it’s a defining characteristic of baroque.

It’s not exactly easy listening, though. It takes effort, and you might need repeated listenings to really comprehend a piece’s complexities.

And it’s not like you could hit the rewind button in 1630.

At about the same time that Rameau published Treatise on Harmony, composers started writing simpler pieces. They would write a single melody, one the audience could remember and hum on their way out of the concert, supported by chords as Remeau had outlined.

Imagine all the people leaving the debut of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony going, “Ba na na naaaaah!”

This single, singable, melody line is the first characteristic of the classical period. It’s called homophony, with homo- meaning “one” and -phony meaning “sound.”

However, a melody all by itself isn’t really enough. It needs support and context.

Rameau explained how this works, too. Using reason, which was en vogue during the Enlightenment, he found that the overtones a note produces are the octave, the fifth note of its scale, and then the third.

The first, third, and fifth notes of a scale make a major chord.

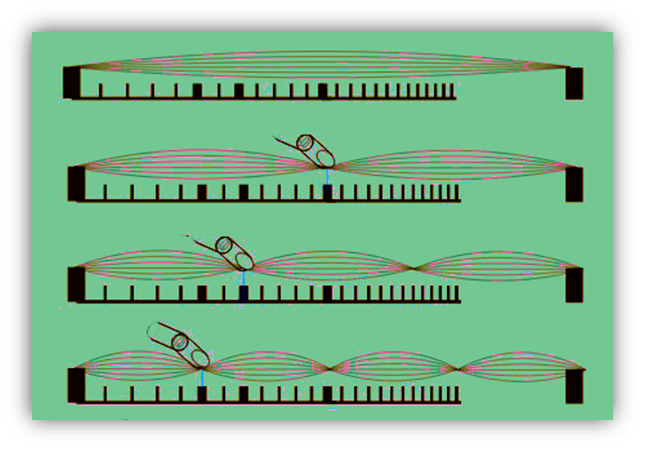

It’s all math, you see, and we can prove this with an experiment. If you have a guitar or other string instrument, pluck a string while holding it down at its exact midpoint. The note you’ll hear will be one octave higher than the string without your finger.

By shortening the string in half, the vibrations double, and double the vibrations gives you a pitch one octave up. Press the string at 75% of its length, and you’ll get the fourth. At 66%, you’ll get the fifth.

The various other notes on the instrument’s neck are precise percentages of the string’s entire length.

Look inside a piano and you’ll see its strings are progressively shorter.

Their lengths have been calculated using a mathematical formula. (The string’s thickness and tension also apply but I won’t bore you with all that.)

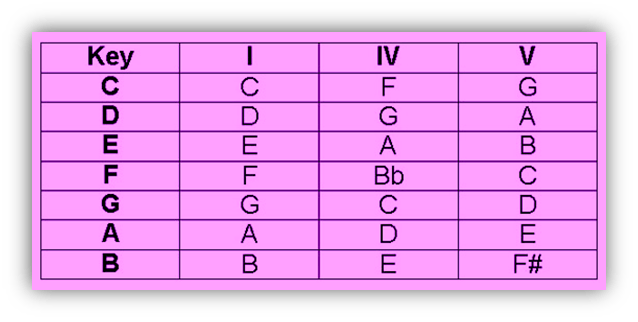

Rameau’s scientific approach to what makes things sound good gave us the major and minor keys, as well as the three chords he called the tonic, subdominant, and dominant.

Nowadays we call them the 1, 4, and 5 chords because their root notes are the first, fourth, and fifth notes of the scale.

These are the same three chords you’ll find in 12 bar blues songs and a whole lotta rock songs.

I’m not suggesting The Kingsmen read Treatise on Harmony, but those three chords in “Louie Louie?” They’re the tonic, subdominant, and dominant. We’ve been using Rameau’s ideas since 1722, often without knowing it.

This idea that music that sounds good based on natural phenomenon is typical of the Enlightenment.

Studying nature showed it has order and balance and symmetry, so music should, too. If you look at the art and architecture of the time, they also have order and balance and symmetry.

By the way, why isn’t “symmetry” a palindrome?

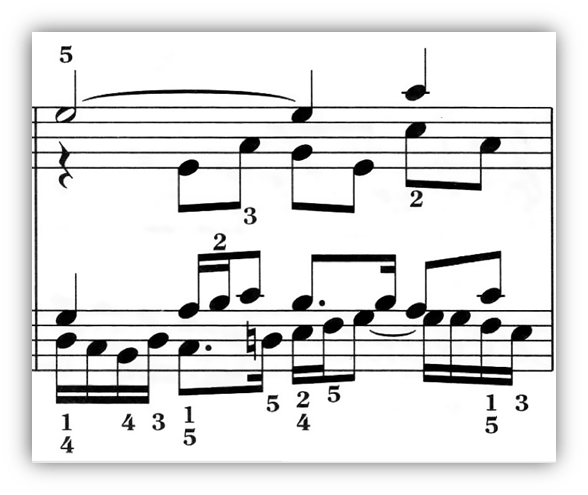

One technique for outlining the chords under a melody is called “Alberti bass.” It wasn’t invented by composer Domenico Alberti but it’s named after him because he used it so much. Chords are three (or more) notes and while they’re sometimes played simultaneously, they can also be played one at a time.

In Alberti bass, the lowest is played first, then the highest, then the middle, then the highest again.

Music from the classical period tries to replicate nature’s beauty. It’s simple, ordered, and balanced.

Mind you, simple doesn’t mean it’s easy to create.

Watch an athlete score a goal with what seems to be no effort at all, and you’re looking at years of sweat and practice. The same goes for composing music. It’s easy to complicate a piece, and much harder to add only what needs adding – and nothing less or more.

Baroque music is complicated and dense. Classical is simple and light. What’s more, the mood of a baroque piece stayed the same throughout. Classical works can change moods in each movement, or even within a few measures.

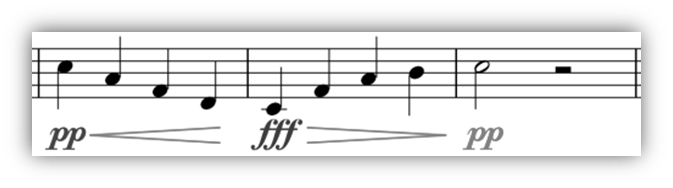

These mood changes were helped along by improvements made to the piano.

The harpsichord had only one volume, but the piano could be played quietly or loudly or at any volume in-between.

This gave composers the freedom to specify the volumes at which notes or passages should be played, and volume indicators were added to standard notation.

A lowercase “p” indicates “piano” or “soft” in Italian. Two p’s means softer still and ppp means very, very, quiet. The Italian word for “loud” is “forte” so “f” means loud, and you can guess what “ff” and “fff” mean.

The composers had more control over everything. In baroque, “basso continuo” was a bass part the composer outlined but the player improvised the notes. In classical, the composer didn’t just suggest – he wrote out exactly what he wanted.

At more or less the same time, composers moved from being hired hands at churches or royal courts to being contractors available to any patron who ponied up the money.

Rather than a king telling a composer to write a piece by next week, the composer could tell the king, “I’ve got three other commitments in front of you.”

Depending on whether the king owned a guillotine or not, of course.

The patrons could be very specific about what the customized piece of music would sound like.

But the good, well-paid composers were the rockstars of their day.

However, composers didn’t really push the envelope. They gave themselves limitations, preferring to work inside frameworks. Nature has frameworks the Enlightenment was trying to understand, and if it’s good enough for God, it’s good enough for composers.

Pop songs have a verse-chorus-verse-chorus framework. There might be a bridge or pre-chorus, but you’re familiar with the structure. In classical, the sonata form became very popular.

The sonata has three parts:

- The exposition, in which the main themes are presented. There are usually two themes, one in the home key and one in a contrasting key. It’s the conflict that’s interesting and dramatic.

- The development, in which the themes are explored and varied even more, and always in several different keys. The composer can really go nuts here and add some imaginative flights of fancy. It can be chaotic or tense but must resolve to the home key by its end.

- The recapitulation, in which the themes are fully realized and are now in the same key as if the conflict has been resolved, even if it’s a tragic resolution in a minor key. Some sort of growth has taken place.

There may also be an introduction and a coda at the end. Regardless, it’s a great storytelling technique, even without lyrics.

The sonata form can be used for a single piano or a full orchestra or any ensemble. It works well with string quartets, which were a new grouping of instruments in the classical period.

String quartets are made up of a cello, a viola, and two violins. Think of all the rock bands that have a lead guitar and a rhythm guitar. That’s sort of why there are two violins.

Even though the classical period gave us innovations like the sonata, string quartet, and symphony, composers mostly stayed with the tried and true.

They didn’t really push the envelope, instead working inside their frameworks. This might be why this refined, made-to-order music is the least favorite of current day musicians. They’d rather play something from the romantic period, which followed classical.

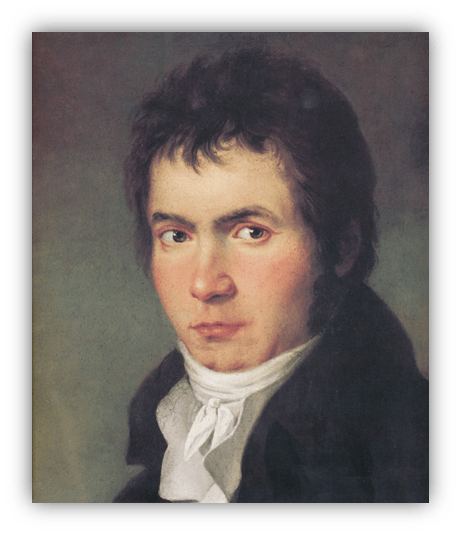

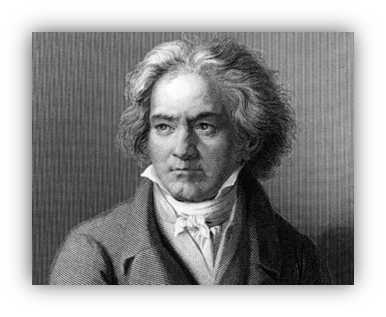

There are exceptions, of course. The big three names of the classical period are Hadyn, Mozart, and Beethoven. You know their music and probably a little about their histories so I won’t go into it, but I want to call your attention to the opening few measures of Beethoven’s First Symphony in C major.

The first chord is a C7. Its notes are C, E, G, and Bb. Wait, Bb isn’t in the key of C major. What the fugue?

This was unheard of. And Beethoven starts with it.

The C7 is now considered a blues chord because of its dissonance, and Beethoven uses it a century before the blues appeared in the Mississippi delta. It resolves to an F major and is followed by a series of dissonant chords that throw us off from the tonal center. It’s lusciously confusing.

What’s Beethoven doing here? Many suggest it’s his little joke on the audience.

But others say it’s Beethoven announcing his arrival on the symphonic stage. “Listen. I’m not like the others.”

And he wasn’t.

The Enlightenment promoted reason, science, philosophy, and individual liberty.

These were all threats to the ruling class, and led to revolutions around the world, notably in France and what became the United States.

Late in the baroque period, there were more public concerts than before and they’ve continued ever since. Making music available to everyone was part and parcel of freedom.

It wasn’t just for the rich and royal anymore. While the music of the classical period may be a little too pristine, it’s based on the advancement of thought, ethics, and science.

And those are good ideas.

Let’s bring them back.

Suggested Listening – Full YouTube Playlist

Giga in G minor

Domenico Alberti

~1730

Melody Overature

Thomas Arne

1733

Sinfonia in G-dur – Allegro

Giovanni Battista Sammartini

~1745

Sonata in A Major, H. 186

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

1765

Concerto for piano and orchestra in C major

Antonio Salieri

1733

Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K. 550

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

1788

Symphony No. 1

Ludwig van Beethoven

1800

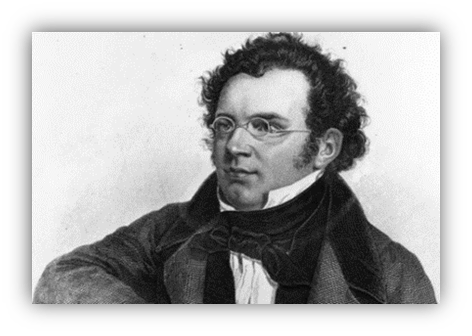

Fantasie in F minor

Franz Schubert

1813

Be sure to let the author know that you liked the article with a “Green thumb” upvote!

Nice! Keepin it classy-cal.

After decades of ignoring him, I’ve spent the last few years really digging into the works of Mozart, particularly his piano concertos. His work is just absolutely beautiful. Even to this day my wife slanders him as an extraverted fop who’s overly concerned about being frilly and pleasant. Which has some truth to it, obviously, but compared to what came before, he brings both passion and more poetic meditation. He is the first to truly elevate the piano to celestial heights, in my untrained opinion. And there are a few works, such as his 24th Piano Concerto, that sound a lot like where Beethoven would soon take the music world.

With Mozart and especially Beethoven, the sturm-and-drang movement in Germany was an important influence and coinciding sentiment. The movement’s concern for heightened passion and drama greatly increased the dynamism of music, and led to an increasing use of dissonance and clamor as well as softer, quieter movements. Those trends continued and amplified via the later Romantic movement, of which Beethoven is thought to be the OG, or at least the grandaddy.

Sometimes the theatrics of Romantic works can be too much for me, and sometimes Baroque feels just a bit too flat. The Classical Era gets at that sweet spot for me: bold as well as beautiful. Intricate yet intuitive. Spicy without snot running out of your nose.

And speaking of keeping it classy, I must post this for…posterity:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C78HBp-Youk

Oh, that Wolfgang. Always bringing up the rear.

I just cannot get into Mozart operas – love most everything else, though.

I just can’t get into operas period, so no worries here!

This period brings to mind the so-called Mozart Effect. Even to the untrained ear most of this music feels very mathematical. You hear a descending and ascending line which then begins again after starting from the next scale step up and then begins again after starting from the next scale step up, etc, etc, etc. I actually DO think that listening to this kind of structured music at a young age probably really does promote something in kids’ brain development that is beneficial for musical learning and lots of other kinds of learning.

At worst, this kind of calculated music can be frustratingly boring. But I found that when I was listening to some of your selections today, Bill, that I really was enjoying them as background music. They don’t demand a lot of attention (usually), so they work well as life accompaniment. I avoided the Beethoven, because that stuff is usually so long, and I have tended to like his symphonies that I’ve heard less than the average fan (sorry, Schroeder). I feel the same about Mahler, who I don’t ‘get’, but you’ll probably get to him in another installation.

Looking forward to Debussy and Ravel.

So am I!

A real swerve from the last couple of weeks. We’ve gone from cultural and sociological studies to history, physics and maths (I’m British, that s could make all the difference in a game of Scrabble, an extra three points on a triple word score, so I’m keeping it).

So much to take in as ever. For a classical novice this is invaluable and drawing comparisons between the make up of the string quartet and a rock band really helps makes sense of it.

I got so sidetracked by Newton that I didn’t go into the other formats, like piano trios and clarinet quartets and the like. They’re map pretty well to rock formats like power trios and synth pop bands. Horn-based groups like Chicago and Blood, Sweat & Tears are halfway to a brass ensemble.

Wonderful writing! As someone who knows little to nothing about music theory or the classical period (to say nothing of “classical music” in general), this was all very easy to grasp and enjoyable. Reading these pieces makes me feel like I’m growing a third ear; music has so much more to teach me!

Thanks! I’d love to listen to some more classical but I’m already researching for next week’s installment. Still, can’t go wrong with a little night music.

https://youtu.be/oy2zDJPIgwc

‘Imagine all the people leaving the debut of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony going, “Ba na na naaaaah!”’

https://youtu.be/wCkerYMffMo

The timeline caught my eye. I use the term “baroque” indiscriminately. Whenever I hear an orchestral instrument in a rock setting, I think, oh, a baroque touch. Everything from Eric Matthews(I really like his one-off side-project Cardinal with Richard Davies) early discography to Wang Chung’s Orchesography. Am I missing the point of the original meaning of baroque? If I describe the new recording of “Everybody Have Fun Tonight”, should I just say, oh, it’s the same song, with violins and stuff.

Does the fusion have to be successful to be baroque?

I like Shostakovich. The backstory and context have a lot to do with it. I’m a Soviet-era Russia-phile.

The explanation of the string quartet changed my life in a small way. Maybe I would have found The Juliet Letters a whole lot cooler when I hate-bought it. Oh, it’s Elvis Costello and the Baroque Attractions.

Yeah, it’s confusing. Baroque is ornamental and busy. Classical is much lighter weight. And romantic is somewhere between the two even though it came later.

Then Shostakovich is after that, in the modern period. That’s going to be a tough one to write about, but he definitely rocks.

“What the fugue?” Love it. You’re as good a writer as a teacher, my friend.

Musical Gravity. That is fantastic. I’ve never considered music to have a gravitational pull, but that explains perfectly being left hanging when a musical phrase does not complete its perceived journey, and it messes with your head.

I guess the term Classical is like Rock. It does refer to a specific type of music, but it is more convenient to apply the term in general. Interesting!

We don’t consider it much, but volume really does play a massive role with Classical works, like they were suddenly having fun with this new dynamic. A little bit softer now, a little bit softer now, a little bit louder now….

Nom-nom-nom VDog!