Let’s go way back in time to, oh, six months ago.

That stupid “12” Megaplier ball ruined everything.

Should have just stuck with the scratch-offs.

09-16-2022: That’s when I said here that rock is an umbrella term for genres like rock & roll, heavy metal, grunge, and more. And that R&B is an umbrella term for soul, rap, and disco, etc.

Today, we’ll talk about another umbrella term.

When we say “classical music,” we generally mean anything played by an orchestra or an ensemble made of orchestral instruments.

There’s more to it than that, of course.

There are six clear periods and/or genres that fall under the classical umbrella. One of them is called “Classical,” just to make things more confusing.

Any music written between 400 and 1400 AD is considered Medieval, but let’s be clear: This doesn’t include the folk music of the time.

Wandering minstrels singing the news from far and away were a boon to societies during these thousand years, and ordinary folks made up their own songs as well.

These are genres of their own, passed down through oral tradition.

I haven’t researched it, but one has to wonder if these touring musicians partied like 1970s rock stars, and if there were groupies in each town.

But I digress.

Medieval music under the classical umbrella doesn’t include folk music, only “serious” music. What makes it serious? It was written down. Eventually, anyway, starting around the year 1000 CE, as I wrote about last week.

More importantly, serious music was for a different audience.

Folk music was by and for, um, folks.

You know, regular people. Serious music was by and for the church and the aristocracy. It was bought and paid for by the rich.

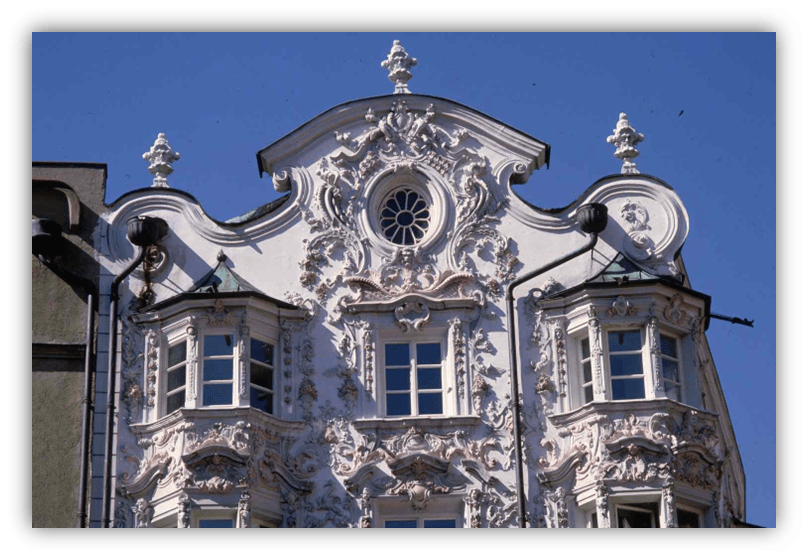

While we think there’s a huge financial discrepancy between today’s rich and everyone else (and to be fair, there is), that discrepancy pales in comparison to the gap between the rich and everyone else of, say, six hundred years ago. I’m sure all of Rupert Murdoch’s houses are nice, but they’re nothing like The Palace Of Versailles.

The unfathomable wealth of the ruling class meant they could afford nice things.

Including composers and musicians.

A king could call in his composer, or more likely have a secretary talk to the composer, and say something like, “Hey, Henri baby, the Duke of Ferrara will be here next month.”

“How about you whip up a 40 minute ditty for my full orchestra? Something, you know, impressive.”

Rich people like impressing other rich people with how rich they are.

Things changed over time. For the Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque periods, music was mostly sponsored by the church. It was religious music for religious people. Later, in the Classical and Romantic periods, it gradually changed to funding by the ruling class, and then to foundations and other organizations supported by rich people. That’s still pretty much how things operate in classical music today, though many composers have found more reliable income in film scoring.

So let’s zoom in on the Baroque period, which was from roughly 1600 to 1750.

Baroque is distinguished from other classical genres by several characteristics.

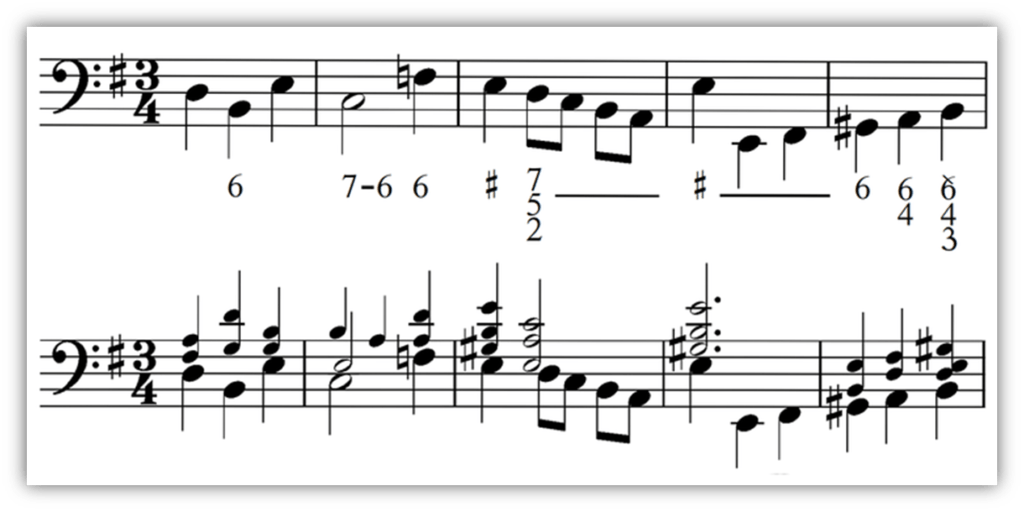

It’s not all about that bass, but a continuous bass line is a big part of baroque.

Known as basso continuo, it’s a constantly moving bass part. Basso continuo is not much different theoretically from the walking bass lines found in jazz and the blues, and it’s often a melody of its own.

This idea of having multiple melodies going on at the same time is a defining feature of Baroque. Known as contrapuntal or counterpoint, it’s when each voice of a composition has its own melody that could stand separately as a solo piece, but when played simultaneously with the other melodies, creates new harmonies and chords as the piece progresses.

Sometimes in music, there’s one main melody and the other parts play supporting roles. This is known as homophony.

You’re familiar with it from pop music where there’s a main vocal melody (and maybe a guitar solo or something) and everything else works as a foundation.

Baroque often uses polyphony, which is two or more melodies going on at the same time with each having equal importance. A piece written for a quartet of instruments might have four melodies, or a single melody played at different times.

You know “Row Row Row Your Boat” as a children’s song. And if you went to a summer camp as a kid you probably sang it as a round. One group would start it off, then a second group would sing exactly the same thing but starting later. A third group would start even later, yet somehow the three parts sound good together. This is polyphony at its simplest.

Now, let’s do “Master Of Puppets!“

Polyphony makes baroque denser- a little more difficult to understand because you have to pay attention to all the parts. It takes some brain power to get the composer’s intention. Baroque is not background music. It’s an intellectual exercise for both the composer and the listener.

In addition to multiple simultaneous melodies, Baroque usually uses ornaments. These are ways of making notes fancy, such as a trill. A trill is done by playing two notes a half step apart, like C and C#, rapidly. Sometimes, depending on the composer’s instructions, it’s done once, sometimes it’s done as many times as you can fit it.

A more obvious thing that makes Baroque distinct is the instruments.

There were no synthesizers or electric guitars in the 17th Century, so they’re not used, but the piano hadn’t been invented yet either. So a lot of Baroque music was written for the harpsichord.

The major difference between a harpsichord and a piano is how the strings are vibrated.

In both cases hitting a key on the keyboard sets a particular string inside the instrument vibrating.

With the harpsichord, the string is plucked. With a piano, the string is hit by a small, felt covered hammer.

This gives the harpsichord a sharp, piercing sound and the piano a warm pure tone. Also, there’s no way to control the harpsichord’s volume. The string is either plucked or it’s not. On a piano, each note’s volume is controlled by how hard you hit the keys. (The piano’s full name is either pianoforte, which is Italian for soft-loud, or fortepiano, meaning loud-soft.)

So, necessarily, there’s no dynamics in harpsichord music. While other instruments of the time, like the oboe, recorder, and strings, could be played at varied volumes, it just wasn’t considered very important.

Speaking of the various instruments of the time, Baroque also brought in something called idiomatic writing. Composers started writing different parts for different instruments, keeping in mind each instrument’s sonic qualities. In prior centuries, the various instruments played the same part and used the same sheet music, if any. Baroque composers wrote different music for each instrument.

But perhaps the biggest change that the Baroque brought in terms of music theory is the switch from modality to tonality.

This isn’t the place to go deep into theory but modality was based on modes, which are still used today in jazz and other advanced genres. Modes are scales with the half steps in different places, giving each mode its own melodic and emotional characteristics.

Tonality, on the other hand, is built on a hierarchy of notes, with the tonic being the most important. In the key of C major, for example, the tonic C is the center of the piece. It’s “home” and will likely be the last note played, giving us a sense of release after the tension of all the other notes (some being more tense than others).

The switch to tonality mirrors the changes in the sciences. Rationality, making sense of the chaos of the other notes of the scale, is the ultimate goal.

And the ornaments and other flourishes of the melodies are similar to the ornate architecture and art of the time.

The last part of the Baroque period saw the rise of Rococo, a particularly fancy decorative style.

It’s helpful to remember when the Baroque period happened. It was the Age Of Enlightenment, where reason became more valued than superstition. Therefore, human brain power was celebrated, and not just in philosophy and the sciences. The arts were a symbol of all that man could achieve, so Baroque music had to show just how smart we are. It’s complex and deep, and requires intense thinking to compose, and almost as much thinking to comprehend.

The big names of the Baroque period that we still know today include George Frideric Handel and Antonio Vivaldi.

But by far the biggest rockstar, the Beatles of the Baroque, was Johann Sebastian Bach.

He came from a family of musicians and he raised a family of musicians. He was a relentless composer of intricate counterpoint fugues and concertos, and was one of the most renowned organists in history.

And there was a lot of bitterness when he went solo.

Remember what I said about idiomatic writing, where each instrument gets its own part? In Bach’s contrapuntal organ pieces, each hand, and sometimes each finger, got its own part. And he played the bass lines with his feet at the same time.

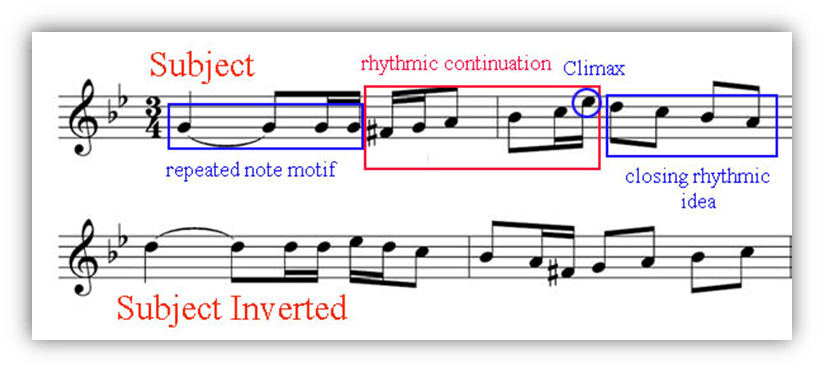

Such was his genius that he could improvise fugues.

A fugue is a piece of music that uses the same theme (that is, a repeating short melody) in multiple contrapuntal parts.

For a normal human being, these could be carefully thought out and written and revised.

Bach could do it on the fly. He is everything you need to know about Baroque music, though don’t let that stop you from searching out the others.

And we should note that Georg Philipp Telemann was born before Bach and Handel, and died after both of them, and he wrote more pieces than both of them combined. He was also more famous than either at the time. Bach, however, is now regarded as the main man of Baroque.

What I haven’t mentioned is the growth of opera during the Baroque period. That will have to wait for another day, but probably not soon.

Next week’s topic will be nothing at all like the Baroque period, and only lasted a few years.

Stay tuned.

Suggested Listening – Full YouTube Playlist

Mystery Sonatas (Rosary Sonatas), n. 1

Heinrich Ignaz Biber

1674

Rondeau from Abdelazer Z570

Henry Purcell

1695

Aria Quarta – Hexachordum Apollinis

Johann Pachelbel

1699

Fugue in G minor BWV 578

Johann Sebastian Bach

~1705

Concerto in D Major Op. 6 No. 4

Arcangelo Corelli

1714

Gloria in D Minor RV 589

Antonio Vivaldi

1715

Water Music

George Frideric Handel

1717

Oboe Concerto Op. 9 no. 2 in D minor

Tomaso Albinoni

1722

Ouverture in D Major, TWV 55:D18

Georg Philipp Telemann

1733

Sonata in D minor, K. 1

Domenico Scarlatti

1739

Pièces de Clavecin en Concerts, 1er Concert

Jean Philippe Rameau

1741

Flat Baroque

The Carpenters

1972

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” upvote!

When I saw baroque my first instinct was that we’d be in the late 60s and A Whiter Shade of Pale would be making an appearance. Obviously I quickly saw the error of my philistine ways.

There’s a lot to consider here, I feel like I need to read Bach through this one to fully appreciate it. I’ll admit, my non classical inclinations tend to gloss over anything orchestral but there’s a lot of interesting stuff to take in.

If it ain’t Baroque, don’t fix it.

Or maybe that should be if it is Baroque, don’t fix it.

Great write-up!

For much of my youth, really all the way until I went to grad school, I dismissed the work of Bach and other baroque artists as stuffy, foppish nonsense for ancient rich people.

Coming from a blue collar family, and later entrenching myself in more anti-establishment movements like punk and indie rock, the class dimensions of classical music–and especially Baroque music–clouded any real appreciation of the music itself. I felt like it was looking down upon me, and so I looked at all of the ways in which it could be seen as decadent, ostentatious, ridiculous, and nowadays irrelevant.

I’m glad I got over my insecurities, as there are so many treasures to be found in the works of Gabrieli, Vivaldi, Handel, and Bach most of all.

I would say, however, that since Baroque music lacks prominent dynamics especially in volume, it ends up being something that can be good background music if you want it to be, but is also ultra-rewarding if you pay it any attention. That’s one reason why I soaked it up in my grad school days, playing it in the background as I was studying.

I started my dive into classical with Romantics like Berlioz and Mahler–and that is way too dramatic for background music! Same with Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakoff, and especially Stravinsky. It was the Brandenberg Concertos and Vivaldi’s Four Seasons that showed how comparatively modest Baroque music could be.

Yes it’s frilly and intricate, but it’s also just more conventionally pleasant and beautiful than a lot of other music, often plaintive and meditative when not outright joyous.

Excited for the next chapter, as I’ve been deep into a listening kick on the most prominent artist of that era. 🤓

I don’t think the next chapter is what you think it will be. Guess you’ll just have to come back in a week and see. 😉

🤔

YOU’RE COVERING EMO!!!! 😀

youre covering emo

^

{Couldn’t resist. Feels like emo is a “lower case, no punctuation” thing.}

You misspelled SCREAMO, thegue

Disco got a bad rap.

Paragraph three is how Sofia Coppola, which critics who have the knives out for her, being a “nepo baby” before the term was coined, misses, is how she critiques the rich in Marie Antoinette. It’s not the fetishization of the privileged as some film critics would like to believe. You don’t see the “blue collar” families, but you hear them in songs like “Natural’s Not In It”.

What made the Beatles so revolutionary was them borrowing structure from classical sources, particularly baroque, and grafting it on to the energy and instrumentation of rock & roll.

50’s rock & roll was very simple. Everybody went I–vi–IV–V and that was it. Chuck Berry didn’t even tour with a regular band. He had the venues he was playing in round up some locals and he would just tell them “This is a blues riff in B. Watch me for the changes, and try to keep up“, as homaged in Back to the Future. There was no walking bass line or anything like that.

The Beatles, and the rest of the British Invasion bands, brought a different sensibility. Their songs were precisely timed and constructed. They wrote idiomatically and used counterpoint. But they kept the drive and youthful outlook of rock & roll. They continued to sing about cars & girls. That synergy between the old and new is what allowed rock music to remain the dominant force in popular music for decades.

Yes! The three B’s, Bach, Beethoven, and Beatles.

And Benny Lane. (It’s a 10)

…

Man, Benny Hill popping up in two consecutive comment sections. He’s the new (original?) Mr. Blobby!

Bill, this is great stuff. There is some classical I love, and plenty I find boring, or even irritating. Baroque seems to me to be perfect background music. A lot of it isn’t quite “hooky” enough to invest a lot of attention from me, but sometimes it’s just the kind of classy, peaceful music that sounds like a perfect soundtrack for life.

You spelled out what I already kind of felt about Baroque…it’s kind of show-offy music. Doing so much in each part. It’s complicated and busy and sometimes dense. You’re knocking these out of the park!

And mt58, your humorous intrusions here are top notch!

❤

Perhaps “allegedly humorous.” But thanks, Link!

BTW: Band name alert:

OK. everybody; Let’s give it up for:

“THE HUMOROUS INTRUSIONS!”

And before he went solo; Benny Lane and the Humorous Intrusions!

I think “The Allegedly Humorous” would work as well.

Love this. I have a niece who has played bass in orchestra from about 8th grade up to a professional level in different cities. I have learned from her that “classical” is not all that she plays, but this is the clearest description of some of the differences that I have ever read. Can’t wait to read the rest and then impress her at the next family gathering.

I’m sitting in a hair salon at the moment, so I can’t listen to the suggested playlist, but I do remember from music class eons ago that Baroque was definitely one of my favorite classical styles. Just an aural buffet of melodies. Lots of excellent info today Vdog, thank you as always.

And mt, the thought of kiddos launching into a campfire singalong of Master of Puppets totally made me hoot out loud. 😂

I wish Rabbits-squared were here to enjoy the “Bach-Turner Overdrive” cover.

I told him and he had nice things to say (about this article but mostly about Randy Bachmann) but I don’t think he’s made an account here. Yet.

And, Bill, love your writing as always: It’s not all about that bass, but a continuous bass line is a big part of baroque.

This was not an article about President Obama, as I expected…. weird….

Great writing – I’m learning so much from these columns!

Rupert Murdoch’s houses are nicer than Mick Jagger’s houses.

Like so many of the others here, I used to think that baroque music was too controlled, too repetitive, too monotonous to hold my rock’n’roll attention. But then I realized something…

People haven’t changed. When you hold on to that thought, you start to look for the fun, the flirtatious, the angry, the sexy, the naughty. You know that Toccata and Fugue organ music which indicates that makes the hair stand on end? The guy who wrote that had severe anger management issues. He once got into a street fight – the bassoonist drew a knife, Bach drew a sword.

Here’s a Bach Fugue by one of England’s 60’s sex symbols, Julian Bream. He plays with a lot of color and variation – the piece is not just one riff piled on another, it develops through different moods.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=spUT-2tU2Yk

Just a fantastic article, Bill. And mt58’s peanut gallery asides are the best.

To be honest, Bach gets to be a bit much for me. I like my counterpoint with more space, like this Elizabethan, borderline early Baroque piece played by the man whose book taught me guitar. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l8AUxnFVNOg