Well, the “J” stands for “Japanese.”

And “pop” is short for “popular.”

So “J-pop” is: “Japanese Popular Music.“

There. That was easy. I guess we’re done here. Last one out, turn off the lights and lock up.

{…Offstage, we hear a bit of whimpering…}

What’s that, Goodboy? There’s a “minimum word count?”

Oh. OK. Let’s dive in.

J-pop is quite different from traditional Japanese music.

The country’s folk music was often sung without instrumental accompaniment. Its classical music was only performed for royalty and their ilk.

Common instruments included several types of flutes and other woodwinds, lutes, zithers, and really big drums.

Whatever the genre, musicians approached it not as entertainment, but as a meditative and strength building experience.

J-pop, on the other hand, is very definitely meant for entertainment and the masses. It’s played on Western instruments in Western styles with a Western tone. It’s Western music as heard by Eastern ears.

This reimagining goes back at least as far as the 1920s when American jazz arrived in Japan, as I mentioned in last week’s article about City Pop. The 1950s saw the rise of Japanese artists performing American country and rock & roll songs, and then came the 1960s popularity of original songs sung in Japanese, like Kyu Sakamoto’s global smash “Ue O Muite Aruko” also known as “Sukiyaki.”

City pop was a mainstay of the late 70’s and 80s, until the Great Recession of the 90s changed everything. J-pop started mid-decade but didn’t get really big until after the economy got back on its feet around 1999.

These original music genres, and the industry behind them, had something in common: Japan has a population of 126 million people. That’s a huge record buying market and it’s why the economy is so important to the story.

An artist can be completely unknown outside the country and still sell a million albums. There’s no need to cater to other markets…

…So they don’t.

The biggest stars in Japan rarely tour outside the country. They sing in Japanese (until recently; we’ll get to that) and their record companies market only to domestic consumers.

Despite incorporating hip hop, electronica, and other Western influences, J-pop is uniquely Japanese.

It’s meant to appeal to Japanese people and no one else. If other people like it, fine, but changing the style to attract foreign ears might reduce sales at home. Why mess up a good thing?

The appeal of J-pop might be hard for us foreigners to understand. One important concept in J-pop, and Japanese culture in general, is something called “kawaii:”

That’s the Japanese word for “cute.”

A couple years ago, a software developer I’d worked with before asked me to look at a Japanese game called “Tsuki’s Adventure,” so I installed it on my phone. It’s about a rabbit who hates his desk job in the city and quits when he inherits his grandfather’s carrot farm in Mushroom Village.

It’s not a game you win or lose. There’s no real point to it except to harvest carrots and interact with the village’s other residents. The music is relaxed and pleasant, and the characters are cute.

In the game’s subreddit, players talk about how cute it is. That seems to be its attraction, enjoying the cuteness. Kawaii.

For centuries, visitors have remarked on the Japanese sense of playfulness.

Here in the States, adults only wear costumes for Halloween and at Comic Con. In Japan, it could be any time of year, just for the fun of it. Wearing a Pokemon or Hello Kitty costume on an ordinary Tuesday night isn’t weird. It’s cute. It’s kawaii.

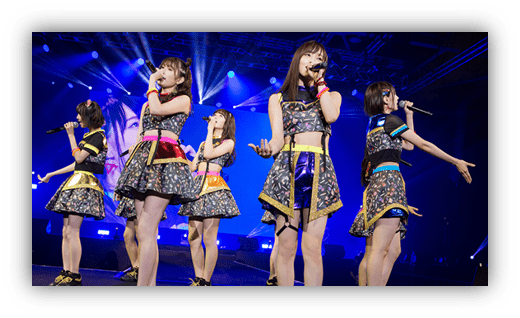

That concept also applies to the music. Performers wear cute outfits and sing cute songs. It doesn’t matter whether it’s a pop song, a dance track, or a metal face melt. It might have a kawaii quotient.

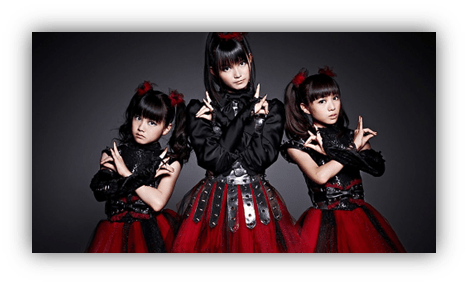

The stereotype is that Norwegian metal bands stand in snow filled forests and try to look threatening while some Japanese metal bands try to look cute.

Kawaii metal. It’s a real subgenre.

And I love it.

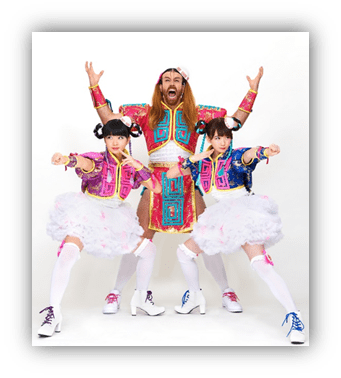

(The male singer in Ladybaby, known as Ladybeard, has his own fascinating story. He may be worth a separate article.)

Kawaii metal is only one of dozens of J-pop subgenres. What they all have in common are catchy melodies, Japanese lyrics with occasional bits of English thrown in, unstoppable and sometimes forced exuberance, and youth.

Youth and pop go together like bubble and gum. The music industry in most countries markets young performers to young consumers. That’s where the money is.

It’s slightly different in Japan.

First, we have to understand the concept of idols. These aren’t historic figures like cancer researchers or Nobel Peace Prize winners.

They’re teenagers who sing, dance, and exude cheerfulness, innocence, and perfection. They’re to be worshiped.

The industry sells the idols’ image. Their music is secondary.

That’s why no matter what you’ll hear when you buy an idol’s CD, the cover will look great.

- Young male idols have young female fans.

- Young female idols have middle-aged male fans.

This strikes us in the west as, well, a little creepy. It’s easy to judge, and maybe we should, but let’s look at this in context.

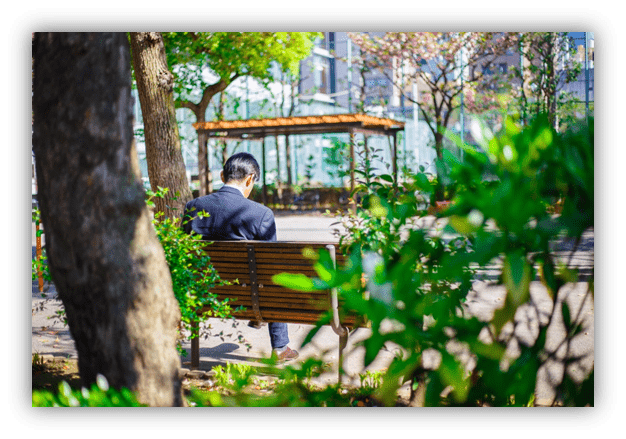

Loneliness is a huge problem in Japan.

So much so that there are rent-a-family companies. If you’re alone and need a brother to take to a concert, or a grandparent to take to a corporate dinner, or you just want someone’s company, you can rent actors to play those roles.

There’s intense pressure on Japanese men in their 20s to earn enough money to support a family before even beginning to date seriously. Some don’t get there by their 30s and 40s, and remain single.

They’re lost and lonely.

And instead of focusing on a family they might otherwise have, they focus, or even obsess, on young idols.

They pick their favorite, buy all the merchandise, attend all the shows, and pay for handshakes and selfies at meet-and-greets. There is the occasional guy who takes it into stalking and sexual abuse territory, but it seems like most fans genuinely look at the idols as platonic daughter figures.

The Japanese music making machine includes talent agencies that sign teenagers, and younger boys and girls, to contracts and teach them singing, dancing, acting, and being cute. Hundreds of teens and preteens sign up every year for a shot at learning how to achieve charismatic idol-hood.

The training process is often videotaped and edited into reality TV shows.

Viewers cheer for their favorites and watch them grow from ordinary kids to idols and, hopefully, superstars, until they retire in their early 20s.

The biggest talent agency is called Johnny & Associates.

One of their better known acts is the group AKB48.

It might have dozens of members at any one time. They’re like Menudo for Japanese girls. And I do mean girls. Some are as young as 11 and when they hit “an unsuitable age” around 22, they “graduate.” That is, they’re asked to leave.

Remember, image is everything here. The girls may have to wear bikinis and lingerie, but they must always present an image of virginity.

Here’s a sample lyric.:

“I want to protect my purity, until I take off my school uniform.”

“Seijun Philosophy” – AKB48

Oricon Chart #1, October 2013

AKB48 members can’t date or have boyfriends. It’s in the contract they signed. When paparazzi photographed a 20-year-old idol coming out of her boyfriend’s building early one morning, it was headline news. She shaved her head and tearfully apologized on television.

The talent agencies prefer younger girls because it gives them longer careers. Fans can get emotionally involved with an idol’s growth as a performer. Idols that master and manipulate these parasocial relationships can go far.

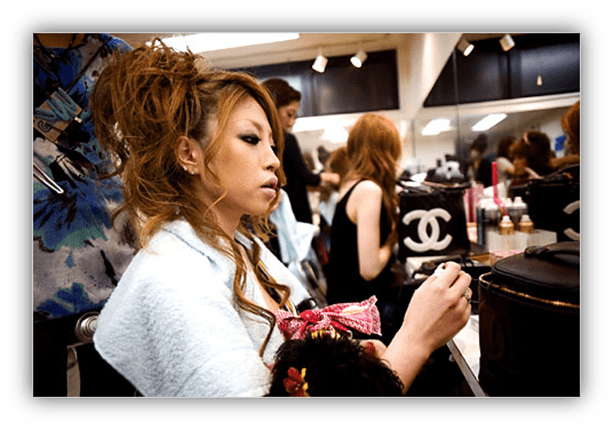

Some idols can’t parlay their audience into a longer music career and turn to working in hostess bars. These are pretty common in east Asia. Lonely male patrons buy overpriced drinks for the hostesses, who earn 50 to 75 percent of the drink prices.

In return, the clientele get the company and attention of a beautiful woman.

It’s worth a couple of watered down highballs at ¥3,000 each to have someone take an interest in them.

This is where the skills the idols learned at the meet-and-greets, the ability to make fans feel close without getting too close, come in handy. Though yes, there is the occasional exchange of money for sex.

There are, however, plenty of artists who work outside the idol system, or after their time within the system, striving to make great music.

Some even develop fan bases outside Japan. This may be because they use western music as a template.

There’s been more English lyrics in recent years, too. It might be a few English words sprinkled in, or an artist might put out two versions of every song, one in each language.

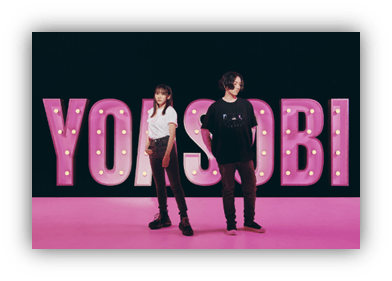

It’s interesting to note that some artists, like the duo Yoasobi, are releasing songs in English only.

Some singers still use high-pitched voices meant to portray youth, but maybe the domestic market alone isn’t enough anymore.

Whatever the subgenre, and they’re pretty varied, their music is almost always crisply recorded, highly compressed, and piercingly bright. Their videos are slick and often futuristic.

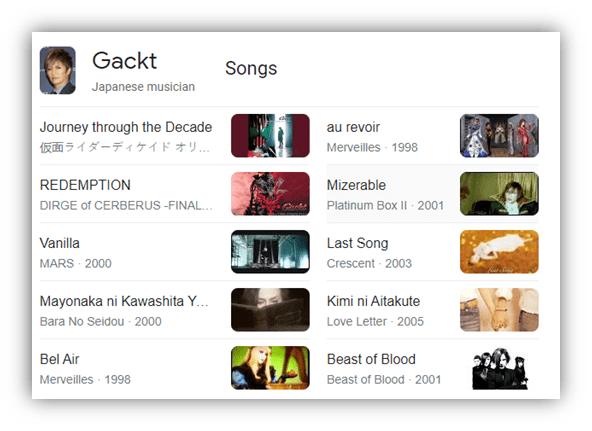

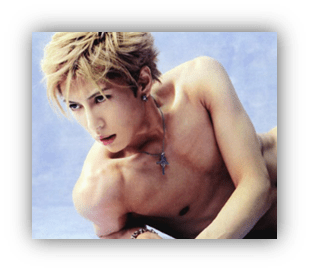

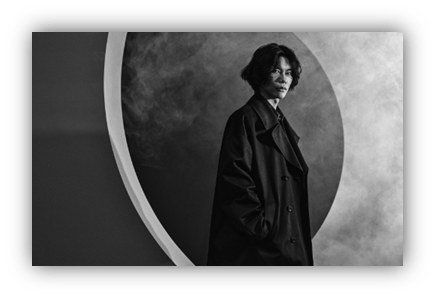

The classically trained pianist and singer who goes by the name GACKT has been charting singles since 1999. He also writes orchestral pieces for film, TV, and video games.

He’s had more consecutive #1s than any other male solo artist in Japan and, oh yeah, he’s sold over ten million records.

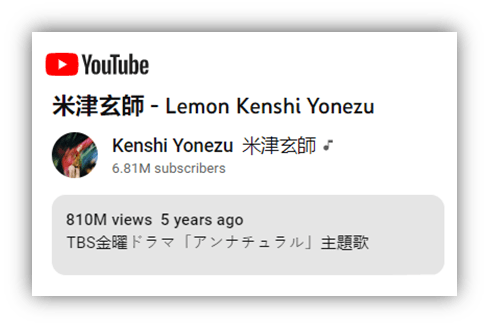

Singer/songwriter Kenshi Yonezu’s song “Lemon” has 808 million views on YouTube.

A pop rock band called Official髭男dism, which somehow translates to “manly mustache,” has a mere 462 million views of their song “Pretender.”

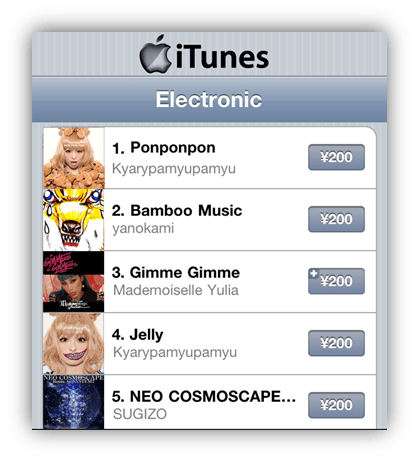

Kyary Pamyu Pamyu is a former idol whose music isn’t much different from the pop you’d expect from idols. However, she has developed a global audience based mostly on her wacky, cute, and colorful videos.

Her first single, “PONPONPON,” sold a million downloads on iTunes in under a year.

The boy band Arashi is also made up of former idols, all from the Johnny & Associates agency. 24 years later, they’re still going strong.

From their first post-idol single until now, they’ve had 37 #1s on Billboard’s Japan Hot 100 chart, and over 50 on Japan’s Oricon Singles Chart.

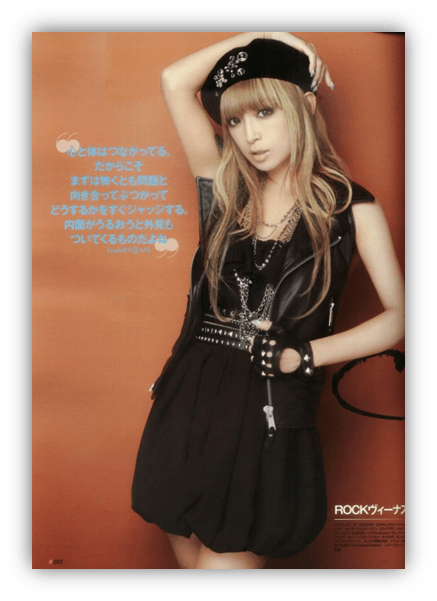

Ayumi Hamasaki has also had 37 #1s.

She writes her own songs about her personal life and other topics, and has been called both the “Empress Of J-pop” and “the voice of the lost generation.”

In addition to music, she’s acted in movies, hosted a TV talk show, and produced clothing and cosmetic lines.

It would be easy to say Ayumi Hamasaki is the Japanese Taylor Swift or Kenshi Yonezu is the Japanese Ed Sheeran.

But that wouldn’t be fair.

While they may sound western except for the language, these are unique musicians making their own art in a culture very different from ours. With the musical similarities and more English, however, expect to see and hear more of them, in the same way that we’re getting a lot of Korean acts on our airwaves.

Now, what’s the difference between J-Pop and K-Pop?

(Aside from the first letter and country of origin?)

That’s for a future article.

See you here next week.

Suggested Listening – Full YouTube Playlist

Mizerable

GACKT

1999

Real Me

Ayumi Hamasaki

2002

Kokoro Odoro

NobodyKnows+

2004

Love So Sweet

Arashi

2007

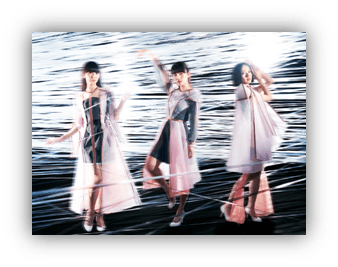

Polyrhythm

Perfume

2007

Everyday, Katyusha

AKB48

2011

Pon Pon Pon

Kyary Pamyu Pamyu

2011

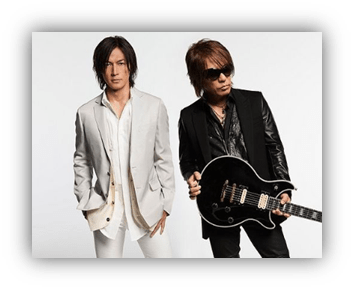

Ultra Soul

B’z

2011

イジメ、ダメ、ゼッタ (Ijime,Dame,Zettai)

Babymetal

2013

ニッポン饅頭 (Nippon manju)

Ladybaby

2015

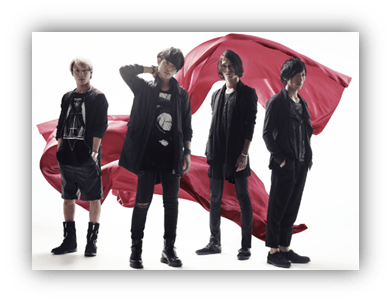

Kyouran Hey Kids!

The Oral Cigarettes

2015

米津玄師 (Lemon)

Kenshi Yonezu

2018

Pretender

Official髭男dism

2019

Monster

Yoasobi

2021

One Last Kiss

Hikaru Utada

2021

Hmm … summer’s coming, and I’ll have more listening time … Thanks for the possible diversion, and the interesting context.

Learning about the forced apology that Maho Yamaguchi had to make was nauseating. This was victim blaming to a farcical degree.

I can only hope that she was able to recover from such terrible treatment, and that those in the J-pop idol management world became more enlightened.

At the bare minimum: good on the fans who supported her.

Agreed, on all counts. There’s something predatory and cultish about the agencies and I hope the system changes. But where there’s money to be made….

I assume Hatsune Miku will be in a separate article

The holographic concerts look amazing and if K.K. Slider ever comes to town, I’m so there.

Thanks for the insight. I knew about the continual churn of singing group members, ‘retired’ once they get too old to be replaced by a fresh batch. I remember a Smash Hits interview with Pet Shop Boys that must be from around 1987. Neil Tennant jokingly said he couldn’t imagine being a pop star long term so they might follow the Japanese model and stay in the background masterminding things as they refresh the talent out front every few years.

I like some of the more out there styling like Babymetal and Ladybaby. While Kyari Pamyu Pamyu looks like the J-Pop equivalent of Paloma Faith.

Not so sure about the name; The Oral Cigarettes. As opposed to which other orifice? By the name and that photo I’m taking it they’re the bad boys of J-Pop.

I thought the same thing about their name and wondered if it’s one of those English phrases that sounds good to someone who doesn’t speak English.

Some other great J-Pop and J-Rock names:

Popcorn Labyrinth

Ripslyme

Bump of Chicken

Juice = Juice

Soil & “Pimp” Sessions

Now I’m beginning to seriously wonder how many of the ludicrous fake band names we’ve come up with for V-dog’s list are already in use by real groups in Japan.

The Oral Cigarettes beats the Croatian surf-rock band The Bambi Molesters for worst international band name.

Bill, you totally turned me on to City Pop last week. I’ve been listening to City Pop compilations for the last week… and I think I mentioned the Teen has some City Pop in his mix, so we’ve been commiserating over that shared pleasure. Not so sure I’ve got a J-Pop bubble coming, but never say never…

Very interesting, BB, especially the way the process of manufacturing idols plays out in Japan vs. the US. I mean here we generally wait until these girl performers are 25 or so until they’re considered ‘unsuitable.’ The Japanese are ruthless.

Yeah, they use the term “Christmas Cake” to refer to an unmarried woman older than 25. Meaning, the Christmas cake that’s still in the shop window after the 25th has come and gone.

Clever, but deeply sexist.

My thumbs up is for your comment, not the “Christmas Cake” concept.

Stephin Merritt would agree.

Marry young, Diana

I don’t want to see you old and alone

And it’s not fun, Diana

I don’t want to see you

Rot in the home for aging spinsters

Compassion. Can’t beat compassion.

Now two related posts in a row? Always keeping us guessing, Bill. If that is truly your name. 🤔

I can’t say I’m a huge fan of J-Pop generally, or at least K-Pop tends to appeal to my sensibilities more often than J-Pop does. Overall, there’s a huge lack of libido in the music, so it often comes off as performative cutesiness.

Of course, given the whole teen idol/middle aged fan dynamic, maybe it’s better that they’re not even more sexualized than they already are. Most Japanese women I know are at least somewhat skeeved at the whole thing, though admittedly most people don’t think much about what a few nerdy fans are obsessed with.

My favorite J-Rock artist is, by far, Ringo Sheena. She is just supremely talented and always compelling. Full of pathos…and libido!

There’s also UA, and Chara, and Yuki. And ya gotta love Kyary Pamyu Pamyu for taking cute to new levels of weird!

This is closer to the music that my 20 year old son (who is gay) listens to most. I’ve never really figured out how he finds new songs, or if there is a particular brand of J-pop that he likes best. But you really nailed it on your two descriptions…highly compressed and piercingly bright. I won’t say the music gives me a headache, but I certainly couldn’t listen to that music if I already had one!

I’m not going to say that I am immune to the cuteness. (Au contraire…I am a middle aged man after all). But it doesn’t seem like a healthy culture of cuteness worshipping. Humans seem to be prone to that problem in many (all?) cultures.

My favorite is “Nippon Manju”. So many Shonen Knife songs about food. Michie Nakatani once got annoyed by a reporter’s insinuation that one of her compositions had a lewd subtext. Think: Kim Deal.

I’ll just leave it there.

Mine, too, with Babymetal right behind. “PonPonPon” is growing on me, too.

Riding on the Rocket? If so, I don’t get the Deal connection.

Is the rocket…gigantic?

“I Wanna Eat Choco Bars”.

Nakatani wrote “Catnip Dream”, as you know. Did you know Jeff Buckley covered it? I wish he completed the whole song. If there was a dance to celebrate the end of an ESL class, “Catnip Dream” is the song I would lead off with.

In the interview, when the music journalist asked what her song was about, Nakatani answered: “I. Wanna. Eat. Choco. Bars.”

That’s silly of the journalist. It’s clearly about chocolate bars! I was thinking maybe “Rocket” because aside from the obvious visual metaphor, the girls sing “Ikou” throughout the song, which is at least close to a phrase that is often uttered upon…liftoff.

Wow, so much to digest in this edition. It’s rather refreshing to read how the Japanese really don’t care to be successful outside of their own country, I never considered that aspect of that industry.

Nor did I ever bother associating Hello Kitty and Pokémon and anime to this ‘cute’ obsession Japan has. But now it makes total sense why they love sticking every game show contestant on TV into a costume! I guess it all stems from the traditional kabuki theater and the ornate costumes they’d wear?

Reading about how lonely the general populace is was rather depressing; I was not expecting to come away from reading this so bummed out. So these idols just become surrogate kids to a nation of adults; that’s terribly sad in so many ways, but at the same time it’s good everyone seems to understand their role.

Thanks VDog for another tasty chapter!