The Wikipedia page for Postmodern philosophy says this:

Sounds like a barrel of laughs, right?

But that’s the philosophy side of Postmodernism. And philosophers are a dour bunch. You won’t see Jean-François Lyotard pranking Noam Chomsky with a joy buzzer, nyuk, nyuk, nyuk.

Got me again!“

The musical genre we call Postmodernism is a little different from the philosophy of the same name.

Musicians can be sticks-in-the-mud, too, but their mud tends to be wetter and more fun to splash around in.

Composers can look at Postmodernism in two ways:

- It can be a rejection of Modernism and everything that came before it,

- Or it can be a license to joyfully create without so many gosh darn rules to follow.

The first is a negative attitude, the second is positive. It’s glass half-empty vs. pour me another.

So Postmodernism isn’t, technically, a genre. It’s a mindset.

It’s the agency to write the music you want to write. It’s kinda Punk Rock without the Rock.

As we talked about last week, Modernism was the rejection of Romanticism, and that resulted in classical (or “art” or “serious…” or whatever you want to call it) music splitting into multiple subgenres. We can see that fragmentation as the invention of new styles, but towards the end of the 20th Century, composers took to doing their own thing without aligning themselves with any particular school of thought.

Each composer is his/her own genre. However, they do share some thinking.

They mix and match ideas willy-nilly. Few, if any, Postmodernist pieces are tonal or atonal all the way through because keeping things the same throughout is a rule, and Postmodernists don’t like rules.

Ideas can be abandoned partway through a piece. Things can change abruptly and seemingly contradict what came earlier. They like contradicting themselves.

On that note, they see Modernism’s failures but use its ideas.

Expect touches of Impressionism or Primitivism, or the twelve-tone technique. Quoting phrases from earlier works is a plus, whether the quote is from a Modernist piece, or Classical, or Pop, or some obscure melody from a completely different culture. Postmodernists embrace all music, whether it’s highbrow artistry or lowbrow schlock. From the silly to the sublime, it’s all good.

And most of it is all meant ironically. Everything – including the piece itself – invites derision and shouldn’t be taken seriously. It’s hard to tell what Postmodern music is genuine and which is winking knowingly.

“But, Bill,” I can hear you asking again, “what does Postmodernism sound like?” Another good question that’s hard to answer because every composer does what he likes without adhering to any set of rules. Let’s just look at some examples.

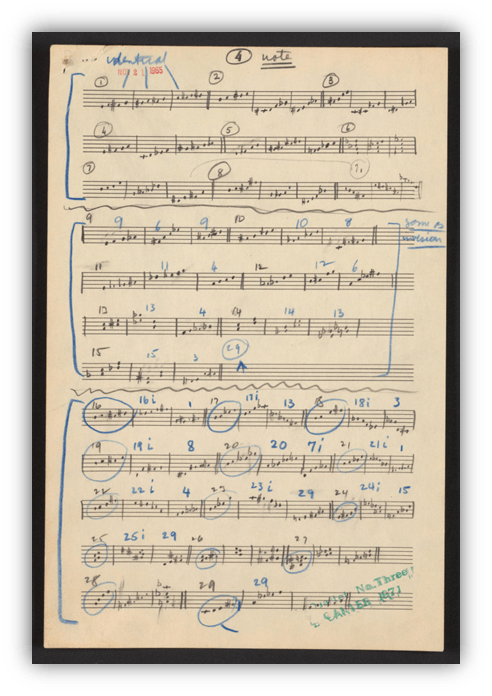

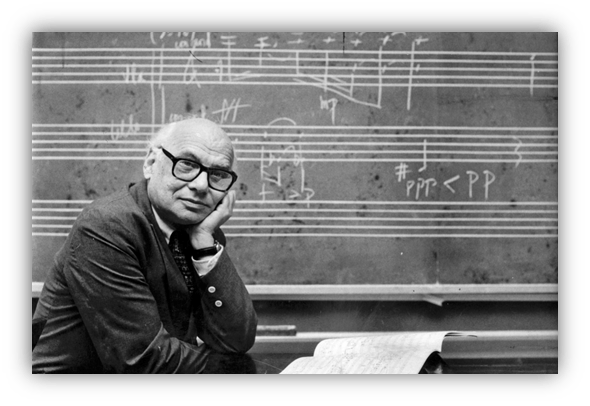

Have you ever been at a party and tried to listen to two conversations at once? That’s sort of what happens in Elliott Carter’s “String Quartet No. 3.” It’s essentially two different pieces of music, one divided into six sections played by violin and viola, the other into four sections played by violin and cello.

The two pairs are supposed to play simultaneously while ignoring each other, with the first playing strictly on the beat and the second playing rubato, meaning they can speed up or slow down as they like. It earned Carter his second Pulitzer Prize.

He was productive for his entire life and finished his last work, Epigrams, in 2012 at the age of 103.

Some composers took a mathematical approach. Allen Schoenberg updated his twelve-tone technique with Serialism, which takes a set of notes or phrases, and reuses them through simple repetition, or playing them backwards or upside down.

Alternatively, a numeric pattern of intervals can be devised and used to determine the next note in the piece. This pattern can also be flipped upside down or backwards. It’s all very geometric and intellectual.

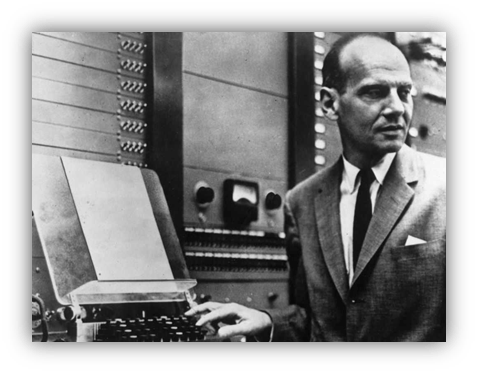

Milton Babbitt used this technique for “All Set,” a piece commissioned by the Brandeis University Creative Arts Festival and premiered with a band led by Jazz pianist Bill Evans.

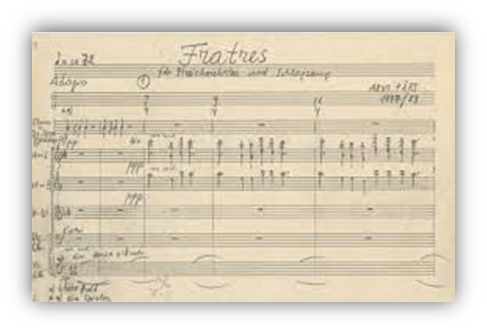

Arvo Pärt is a composer from Estonia who started out as a Neoclassicist and then began using Serialism. Though the Soviet regime eyed his early output with suspicion, because they viewed the avant garde as degenerate, it was his 1968 religious choral piece “Credo” that led to all his works being banned.

A government that’s scared of art and religion probably has a lot of other things they don’t understand.

At that same time, Pärt also found himself, creatively, out of ideas. Despondent, he didn’t write any music for eight years, other than a few film scores he did for the income. He spent that time studying choral music from the Renaissance. A deeply religious man, he converted from Lutheranism to Eastern Orthodoxy during this period.

He also invented tintinnabuli: a technique that pairs a melody note with the next higher or lower note in the underlying chord’s triad.

He introduced it in his 1976 minimalist masterpiece “Für Alina” and a 1977 piano/violin duo called “Fratres.”

The regime still thought his stuff was subversive, but they had other things to worry about, like their war in Afghanistan and Solidarność in Poland, and in 1980 gave him permission to move his family to Vienna. He later moved to Berlin and then back to Estonia, long after the fall of the Soviets.

Pärt’s style has been called “holy minimalism.”

It has long notes, long silences, and few instruments. Even when his symphonies use the entire orchestra, his restraint and delicacy make his sacred work palpable and relatable, something not often found in Postmodernism.

If Postmodernism has any subgenres, minimalism is its most used. It’s simple, repetitive, and meditative. There’s so little in it that it amounts to sensory deprivation. It forces you back into your own head, into a trance, to think your thoughts without distraction.

Another minimalist, John Cage, wrote many pieces for prepared piano.

To prepare a piano, preheat the oven to 425°. Just kidding. There are actually many ways to prepare a piano.

In Cage’s “Sonatas And Interludes,” the piano has screws, bolts, rubber, plastic, and other objects stuck between its strings.

Forty-five notes are prepared this way, and doing so changes their pitch, timbre, and sustain. Some notes no longer sound like a piano.

One of Cage’s other techniques was “Aleatoric Indeterminism,” which is a fancy way of saying “chance.” Most music fans have at least heard of his “4:33,” which is a piece lasting four minutes and thirty-three seconds without any musician playing any notes. What the audience hears is purely random.

It could be someone shifting in their seat, or a sneeze from the balcony, or maybe a fire truck’s siren as it passes the concert hall.

This doesn’t really fit the definition of Aleatoric Indeterminism, because it’s sound rather than music. For real Aleatoric Indeterminism, we need to go to Cage’s “Music Of Changes,” which he wrote using the I Ching to pick the notes and their duration.

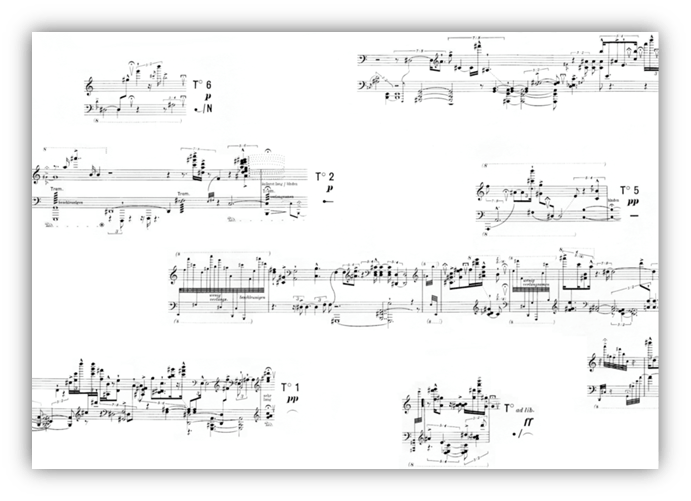

Or: Karlheinz Stockhausen’s “Klavierstück XI.”

In this piece, Stockhausen wrote 19 fragments on the same page, instructing the performer to start with any fragment, and to play them all in any order until one had been played three times. Every performance is different.

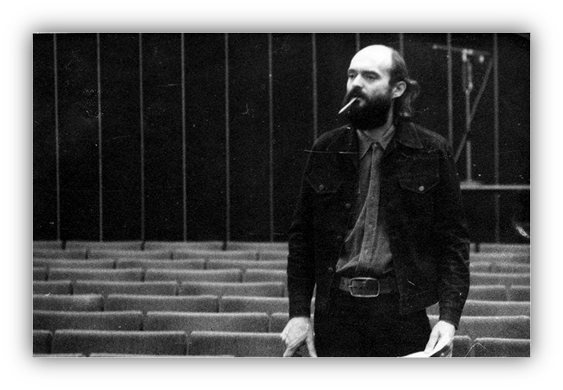

And then there’s the curious case of Danger Music and its best known composer, Dick Higgins.

He was part of the Fluxus movement, which holds that the artistic process is more important than the art produced. In fact, once a musical piece is written, it doesn’t need to be performed at all. The meaningful part is already done.

As such, some Fluxus music is written so that it’s impossible to be performed.

The sheet music for Higgins’ 1962 piece, “Danger Music Number Nine” simply says, “Volunteer to have your spine removed.”

The score for “Danger Music Number Seventeen,” one of the few pieces that can actually be performed, says “Scream ! Scream ! Scream ! Scream ! Scream ! Scream !” He was asked to perform it at a party, did so, and was then asked to leave. I can’t recommend it, but it’s on YouTube if you’re curious.

With every composer going off in different directions, it’s hard to sum up Postmodernism or to say where it’s going from here.

There are very serious composers, like Schoenberg, Pärt, and Philip Glass, but then there are class clowns like Higgins.

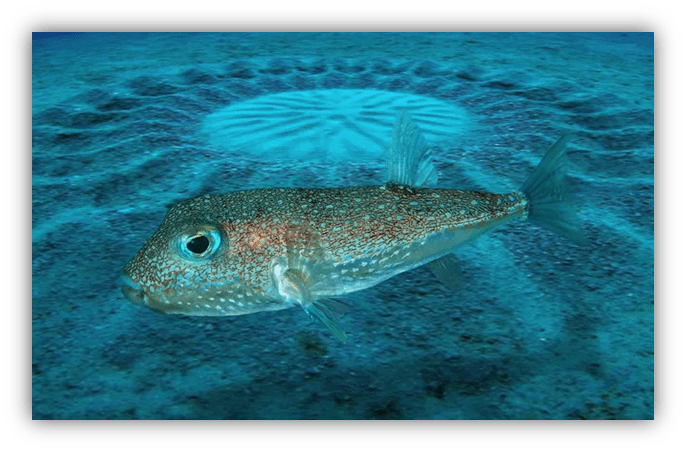

We’ve always thought art separates us from animals.

Though we now know that octopuses decorate gardens, pufferfish create geometric circular designs in the sand, and bowerbirds build intricate architectural nests. Imagine what a bowerbird could do with power tools.

What comes after Postmodernism?

Well, there’s already a philosophy called, I kid you not, Post-postmodernism. Where Postmodernism said Modernism failed, Post-postmodernism says Postmodernism failed, too, and that insightful people will come together to eradicate irony’s importance in contemporary culture.

That’s called Post-irony.

Postmodernism does little to expand its audience. That’s part of its philosophy, that art is for the artists and audiences aren’t important.

I get it.

I’ve had lots of fun making music in my bedroom. Call me shallow, but seeing an audience understand and like your music is joy on a much higher level. It’s called communication.

This is just, like, my opinion, man:

But we have to do better.

We need to start thinking again.

We have to create something genuine without irony, and with love, empathy, consideration, and heart.

I like Postmodern music and recommend the Suggested Listening list below. But c’mon, composers. Don’t use scales if you don’t want to but, literally for goodness’ sake, stop showing each other how clever you all are and create something uplifting.

- The world needs it.

- You need it.

What now?

Suggested Listening – Full YouTube Playlist

Sonatas And Interludes, Sonata V for prepared piano

John Cage

1948

Klavierstück XI

Karlheinz Stockhausen

1956

All Set

Milton Babbitt

1957

Black Angels, Movement. 1, “Departure”

George Crumb

1970

String Quartet No. 3

Elliott Carter

1971

Für Alina

Arvo Pärt

1976

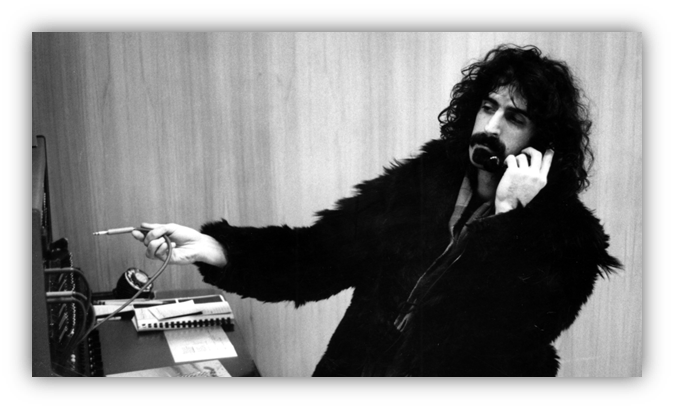

Mo ‘N Herb’s Vacation, First Movement

Frank Zappa

1983

Symphony No. 4, I. Heroes

Philip Glass

1994

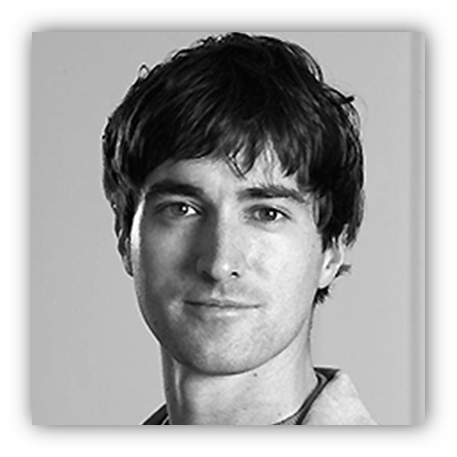

Mothership

Mason Bates

2011

Partita for 8 Singers: No. 1. Allemande

Caroline Shaw

2012

[ narcissus’s nausea ] for esemble + electronics 5.0

Giulio Colangelo

2016

DW28

Bernhard Lang

2017

Enjoy these selected Articles in Bill’s “What Makes…” series:

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

This is the stuff that got me into “classical” in the first place! Even now, as long as there is that Dadaist sense of mischievous glee, or a Zen sense of mischievous wonder, postmodern art has a lot to offer. I do get those qualities from Cage and Stockhausen and even the Fluxus artists.

Admittedly though, it often requires a conscious effort to sit with their music, even my favorite pieces. What is the indeterminacy equivalent of “Jailhouse Rock?”

“Danger Music Number Twenty-Three.”

Ha! I see the post-modernism music wore on you. You have more than once compared music to physical works of art, and some of this music seems like the art in museums whose purpose only seems to be to provoke and push the envelope and break rules. I guess that’s fine…there is a place for that and it helps us keep everything in perspective. But when it’s all done, it’s still nice to have some more orthodox art that brings more traditional beauty and emotion and awe of talent. The most clever person doesn’t always win…sometimes it’s the person with the most skill. (As the story-telling Grandpa says to the little boy in The Princess Bride, “Yes! You’re very smart. Now, shut up.”)

I was thinking Philip Glass today and you mentioned him. I was also thinking of Penguin Cafe Orchestra, one of my favorite groups. Their music is minimilistic, occasionally with odd instruments like telephones and rubber bands…but always with a cozy warmth that makes you feel at home (or at least it does for me). Sometimes I think of it as “NPR music”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RWZ4pve5Mkc

This is great! I’ve only heard their name, not their music, but I like this a lot. Cool and quirky.

I don’t know lots about PCO but that one is instantly recognisable having been used in a telecoms company advert here in the 80s. It took me til a few years ago to find out it wasn’t made specifically for the advert.

I really like Perpetuum Mobile. Came across it featuring prominently in an offbeat Australian stop motion animated film; Mary and Max from 2009. Highly recommend the film as well as the track.

“Perpetuum Mobile” is a good one. It was used in a commercial here in the 90s…here it is, an HP commercial.

https://youtu.be/LpAewxP2j-E

And of course, a remake of their “Music for a Found Harmonium” is the “resolution music” at the end of Napoleon Dynamite.

Today I learned that Spacehog’s “In the Meantime” sampled Penguin Cafe Orchestra.

I’m not familiar with any of the music in this genre, but by the way Tom describes Timbaland, I half expected him to show up here.

Ha! I can’t see that but I can see Timbaland using Philip Glass samples.

Some new discoveries here, as well as some instant “that’s enough of this” reactions when playing the YouTube videos. Cheers for the writeup and links. Arvo Pärt’s F.Alina is heavenly gorgeous! It is a go to when I want to move closer to zen territory (zen is often in a different time zone).

I am not sure Gavin Bryars is post modern or modern, but he combines traditional with the strange. Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet is a personal favorite. I find it engrossing, while others may say “we get it!” The Sinking of the Titanic is also cool, but there is much more to Bryars.

Listening now. I’ve never heard of Gavin Bryars but this is interesting stuff. Thanks for the tip!

I found that performance of #17 to be a bit, meh.

Scream and the world screams with you.

https://youtu.be/eW8XoovSlsM?si=JUjKrof_2Fzbdq1L

That’s beautiful. It’s not why I had in mind as Postmodern musically but it sure is good.

Certainly it’s not. But I’m all about extricating ourselves from our assholes — we reached the endpoint of that process.

I’m more or less stating my agreement with your assertion

We have to create something genuine without irony, and with love, empathy, consideration, and heart.

Thanks, buddy, I love this.

The music you are describing was thoroughly embedded in my music education and the music department of the university at which I matriculated. The music composition department was entirely devoted to it. I didn’t go out of my way to seek much of it out, but it definitely expanded my musical palette and opened me up to new possibilities of what music could be. In my young mind, it was all under the umbrella of what was called “20th Century music”, but of course, there were many different kinds of music that fit that description, including electronic music, such as this piece from my “Intro to Listening” class that I strangely recall above most others-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=alPyT_tp-nY

Ooh, that’s interesting. I can see why they used it for opening ears and probably asked the question, “Is this music?” I can see why it stuck with you.

I think I like the performance art aspect of the class clown branch of postmodernism rather than the actual music. Hadn’t come across Danger Music before but the spine removal appeals on a surreal comedic level.

I probably haven’t given the music a fair enough go. Yet another one to put right.

In one of the more unlikely chart entries, 4’33” reached #21 in the UK chart in 2010. After a succesful campaign the year before to get Rage Against The Machine’s Killing In The Name Of to the Xmas #1 and stop the Simon Cowell backed X-Factor winner, the organisers picked 4’33” the following year. Didn’t quite have the same impact.

The 2010 recording featured (or maybe that should say didn’t feature); John Foxx, Orbital, Madness, Anne Pigalle, Kooks, Ed Tudor Pole, Scroobius Pip vs Dan Le Sac, Billy Bragg, Jon McLure and Imogen Heap.

On Rate Your Music it scores 1.08 out of 5 from over 300 reviews. This one perhaps puts it best;

‘You’d think 4’33” would be impossible to f*** up.

You’d be wrong’

I bet radio stations hated 4:33.

Still, it’s a very funny idea and I’m astounded it charted at all. While I haven’t heard the 2010 version, I think Marcel Marceau did it better.

I can’t remember if they played it on the chart rundown. Possibly not for fear that unaware listeners would think something had gone horribly wrong. I think the general reaction was they were trying to be too clever. Whereas Killing In The Name Of expressed the anti X-Factor sentiment in a catchy shoutalong manner that was easy to get behind.

For what it’s worth, I think 4’33” is a wonderful musical piece. Cage got the idea for it after seeing Robert Rauschenberg’s White Painting. The magic of the work was highlighting how the piece could change endlessly based on chance conditions of lighting and shadow.

Cage employed a similar approach, but as a musical performance of endless possible variation. Compared with Rauschenberg’s painting, it’s more of a “happening,” with the audience acting as musicians, whether they know it or not (but also wind, thunder, rustling grass, and whatever else is around).

Cage was in fact the first to stage immersive art events called happenings. His 1952 Black Mountain Happening was the start, and 4’33” has some of that spirit.

Still, I prefer the radio edit (4’15”).

Also, this anecdote (time stamped) feels relevant:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_lOMHUrgM_s&t=300s

We listened to this in 4th grade music class. Creeped us out. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WaIByDlFINk

And one more thing- “Thoroughly (Post) Modern Billy” is the definition of mt58 bringing his A game.

Heck, it creeped me out a few years ago when I first heard it.

So the guy at the keyboard just holds down the sustain pedal?

Your inclusion of Cowell does raise the question of: when did postmodernism start to creep into music? The Dadaists are the earliest I can think of, but Cowell certainly brought some unorthodox and irreverent approaches to musical performance to the table.

Though he’s often lumped in with the “Ultra-Modernists:”

https://tnocs.com/dude-wheres-my-van-part-16-the-ultra-modernist-meet-and-greet/

The lines are so blurry you could tell me Cowell was a ska artist and I’d believe you.

🙏

I have a theory that once an artform is being taught in universities, it is effectively dead, as more and more artists working in the field begin creating their works to impress academics and develop a contempt for the general audience.

The good news about Classical/Orchestral music is that while the academic strain spun off into exploring the boundaries of what music can be, and how much discomfort can it cause and still be performed, some of the roots and traditions were kept alive and developed through the medium of movie scores and soundtracks.

That’s a sound (no pun intended) theory, and classical composers are definitely doing soundtrack work. That’s where the money is.

I understand the sentiment, certainly the stuff is resolutely fringe, and sometimes antisocial. But i disagree that this hyper-academic stuff was the death of a movement.

The electronic works from this time paved the way for whole swaths of new genres in subsequent decades, and musique concrete opened up how sound was heard and produced. Their influence is felt in tons of later pop albums (Sgt Pepper being just one iconic example) and especially soundtracks. Heck, sometimes these original works are used in film soundtracks, and they become iconic.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GPKg2c_bRCs

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CMbI7DmLCNI

One last(?) thought triggered by the mention of Schoenberg’s 12 tone system For an assignment in music theory class, we had write a composition based on a similar concept. My piece was called NCAA Counterpoint and it was based on the scores from the men’s college basketball tournament the night before. Each note of the chromatic scale was assigned a number. The numbers from the winning scores determined one melodic line, and the losing scores the other. I know there are 10 numbers and 12 tones, so I don’t recall how I worked it all out, but I remember the concept being a lot more interesting than the actual result.

And here I was just thinking it was weird for the sake of weird.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c0DwRAVJZ4A