Music Theory For Non-Musicians™ with Bill Bois

I didn’t like opera. Until I went to one.

Attending an opera and listening to an opera recording are two very different experiences. I highly recommend the former.

And never, ever do the latter.

On record, those high soprano voices hurt my ears. I think that’s an effect of the recording process. Recorded music sounds different from live music.

Sopranos sound shrill on record.

you might be at the precipice of an enormous crossroads.”

They’re shrill in a live setting, too, but much less so. I think that’s because the sound dissipates through the room.

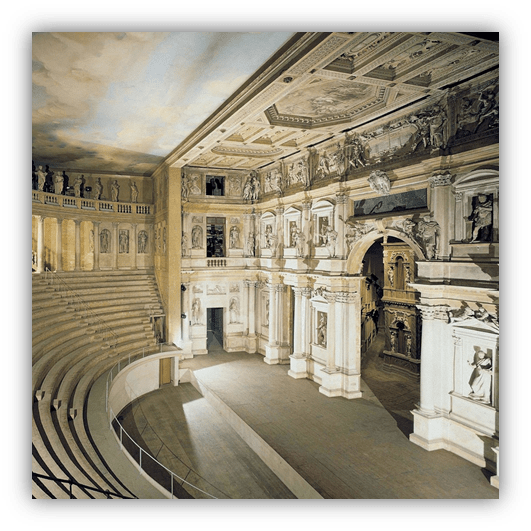

Plus opera, being a partially visual medium, loses something if you’re not sitting right there in the theater.

Opera singing is unnatural. No one sings that way when sitting around a campfire.

There’s a reason opera performers sing like that, of course, and it’s because they have to be heard and understood in the third balcony without microphones. There’s an orchestra in the pit between them and the audience so they have to project over the orchestra and into the farthest reaches of the auditorium.

In some ways, it’s not much different than yodeling from one mountainside to another.

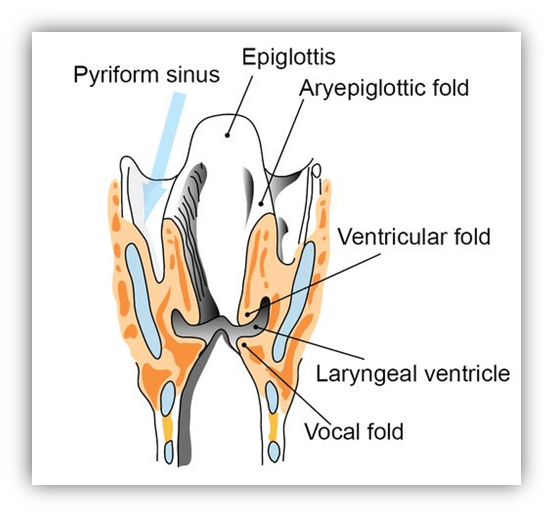

So opera singers develop their squillo. That’s a technique for producing overtones above the fundamental note they’re singing. The overtones help the vocals pierce through the air and get to the back row.

It’s done by narrowing the aryepiglottic folds of the larynx.

Serious training and practice and an understanding of one’s own anatomy are required to be able to do it.

Squillo sounds bright, and a similar technique called scuro sounds dark. Most opera singers combine the two to sound bright yet full bodied, and this is called chiaroscuro, meaning “light-dark.”

These three words, squillo, scuro, and chiaroscuro, are all Italian.

That’s not surprising because opera is a mostly Italian invention.

Let’s go back to Florence in the 1590s.

You may remember from my article on baroque that classical music was sponsored by the church and royalty.

The church had their own reasons. But royalty had court musicians and composers almost entirely to impress other royals, and to remind their underlings how rich and classy and fabulous they were.

It could be argued that nowadays rich people donate to public broadcasting and build new chemistry buildings at prestigious colleges for the same reasons, not to mention the tax deductions, but I won’t go into that further here.

Anyway, a group of scholars got together in Florence sharing a desire to enrich Italian culture. They came to believe that the ancient Greeks produced the best dramas in the history of mankind. Those plays brought audiences from far and wide, and influenced people to go home and make their lives better. Such was the strength and brilliance of Greek drama.

The scholars called themselves the Florentine Camerata.

They hoped to create works of dramatic art as great as the Greeks.

They came to believe that the ancient dramas were sung, at least by the Greek choruses, and that’s why the plays had such an emotional, uplifting, and life altering effect on their audiences. It’s the music.

At the same time, royalty sponsored masques.

Masques were musical spectacles with singing, dancing, and elaborate scenery. The songs very often told stories about the king, queen, prince, or other royal sponsoring the event.

The stories were very complimentary, of course, and the royal family in question often participated in the finale.

The Florentine Camerata took the idea of all-sung productions from masques and tried to combine it with the serious drama of the Greeks. They hoped to create dramas with inspirational story lines, fantastic music, and well-crafted sets.

Remember that part of music during the renaissance and baroque periods was counterpoint, which is having multiple melodies going on at the same time. That’s fine for harpsichord or pipe organ, but if it’s several voices singing their own lyrics, it becomes impossible to understand what any of them are saying.

So to make things simpler, composers started using monody:

A single voice singing a melody over chords provided by the instruments. One voice plus one melody equals easily understandable lyrics. That’s pretty important when you, as a composer, are trying to tell a dramatic story.

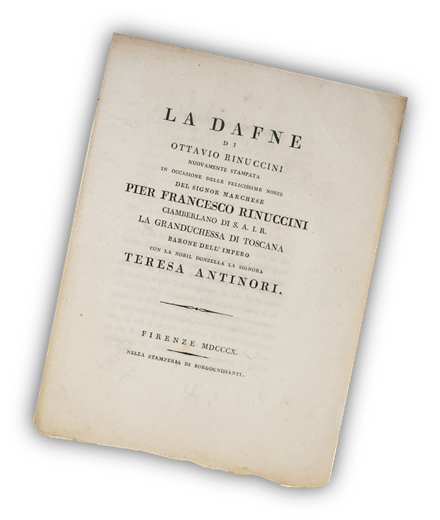

In 1597, the poet Ottavio Rinnucini and the composer Jacopo Peri, both members of the Camerata, wrote “Dafne.”

This was the first opera.

Sadly, none of its sheet music survives. We have its libretto, its lyrics, so we know it’s about the love between Dafne, a nymph, and Apollo, who was the Greek god of music, among other things.

We also know the instrumentation was only five instruments: harpsichord, viol, lute, archlute and triple flute.

However, we don’t have any of its melodies or arrangements.

It was a hit. Five years later, Rinnucini and Peri produced “Euridice” and that was a hit, too. Fortunately, we have its music and libretto, and it’s still produced every now and then.

The Duke of Mantua heard “Euridice” and asked his poet Alessandro Striggio and his composer Claudio Monteverdi, (because everyone has a poet and composer on staff,) to write an opera for him. “L’Orfeo” debuted in 1607 and was yet another hit. Soon, every royal in Italy had their staff artists producing operas.

With instructions to outdo the other guys.

The Florentine Camerata had set about to improve humankind’s condition with inspirational works of drama, but the need to please royal egos led to productions that were less intellectual and more ostentatious.

This happens in every genre.

There may be a spectacle happening at your local arena..

But don’t overlook the band at the bar down the street. There’s some amazing art happening there, too.

The first public opera house, San Cassiano, opened in Venice in 1637.

It gave regular folks the chance to experience opera. It had a very small staff of singers and musicians, and was funded only by ticket sales, so they had to appeal to the public to keep the doors open.

It succeeded, and that success led to three other public theaters opening, sponsored by rich families who wanted to seem benevolent.

Given this new competition, San Cassiano hired the great Monteverdi, who was in his 70s at this point, to write new operas for them. Due to the small cast, as well as budget restraints, he went back to the Camerata’s ideals and wrote works meant to inspire goodness. “Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria,” for example, tells the story from the second half of “Homer’s Odyssey” and how virtue is rewarded in the end.

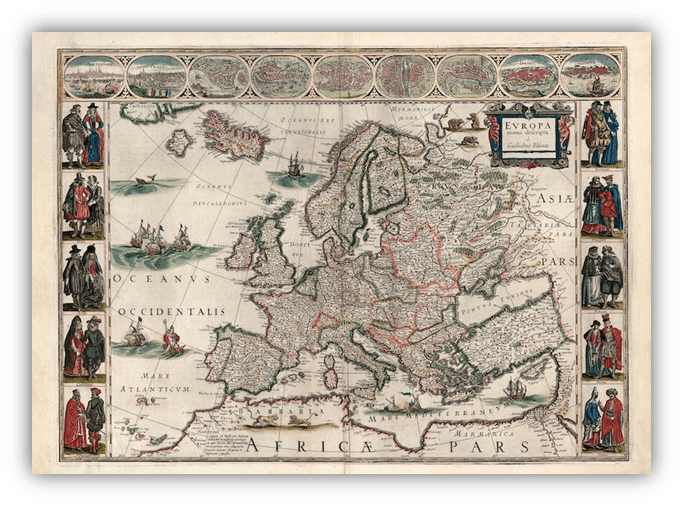

Opera soon – well… soon for the pre-radio age – spread across Europe.

Each region gave opera its own spin, notably in the way it treated dialog.

The Florentine tradition had been that all words should be sung, and there were two ways of doing this. There are arias, which are true songs, and there is recitative singing, which is the dialog between arias done in a sort of speak-singing. Recitative parts are speaking with melody.

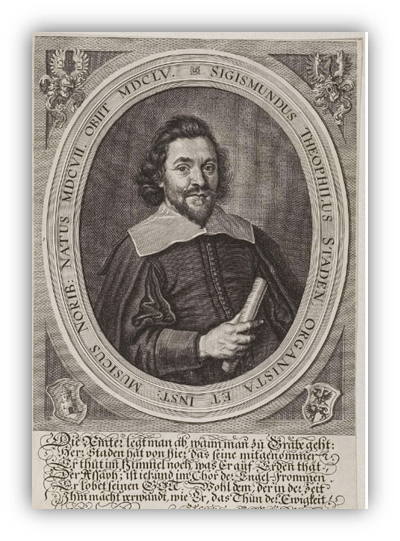

- In Germany, Martin Opitz translated the libretto to “Dafne” and Heinrich Schütz set it to new music. Like the original 30 years earlier, the music is now lost, but it was the first German language opera.

- In 1644, Sigmund Staden wrote “Seelewig,” which used spoken dialog rather than recitative singing. This predates what would become known as “English opera” by several decades. In most regards, however, German opera was overshadowed by the Italians.

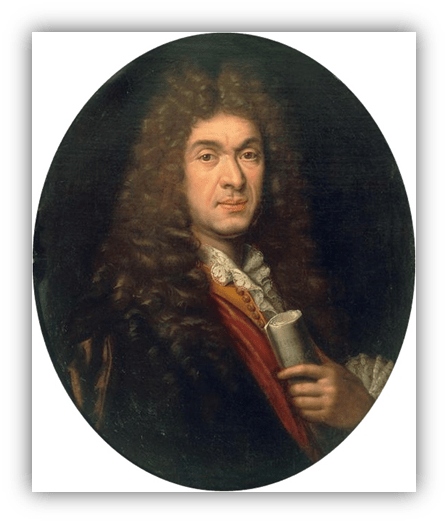

- Giovanni Battista Lulli moved from Florence to Paris to work as Mademoiselle de Montpensier’s chamber boy in 1646. Already a violinist, he studied with her musicians, began composing, and changed his name to Jean-Baptiste Lully.

Lully meticulously wrote his recitative melodies to imitate the speech patterns of dramatic actors, pausing where they would pause, and emphasizing what they would emphasize.

This approach influenced French opera for a century.

English audiences, however, didn’t like the recitative parts at all. On British stages, songs were sung and dialog was spoken, and that’s all there was to it.

Additionally, there had to be some explanation as to why a character would suddenly burst into song.

It just doesn’t happen in real life, so the British thought it shouldn’t happen on stage. If, however, there was some otherworldly explanation like magic or other fantasy, then sing away.

The result is what’s called a semi-opera or English opera where there’s dialog and no recitative vocals.

In 1691, Henry Purcell wrote “King Arthur.” It’s about the Saxons battling Arthur’s Britons, yet includes familiar imaginary characters like Venus and Cupid so there can be arias.

Meanwhile back in Venice, Monteverdi’s pupil Francesco Cavalli took over as the leading opera composer. The music itself became the focus of opera, and the story played second fiddle.

Something similar happened in Naples.

With Alessandro Scarlatti at the forefront of Neapolitan music, elegance and seriousness became very important. Vocal talent was prized above all else. Scarlatti’s contributions include the final forms of both the three part overture and the da capo aria.

A da capo aria uses an ABA form, with the first part repeated at the end. The middle section acts like a bridge in a modern pop song, expanding on the main idea or introducing other concepts and melodies. It can even be in a different key or tempo.

“Da capo” means “from the head,” as in go back to the start of the piece and repeat the first section. The term “head” is widely used in jazz to indicate that beginning section. In jazz, the middle section is where the improvised solos go, but in both jazz and da capo arias, after the middle section, you go back to the head.

The point of arias became to showcase the singers’ capabilities. The composers’ job, therefore, was to write showcase pieces, while telling the story. The singers, however, could improvise a little, and show off their vocal prowess by ornamenting the melodies with trills and other flourishes. We have the names of the great singers, but no recordings. Obviously.

Thanks to sheet music, however, we can still see who the great composers were.

For royalty in the 1600s, you weren’t hip unless you had an Italian composer in your court, or at least one who had been trained in Italy.

There was great work coming out of other countries, but Italy was where it’s at.

That brings us to the 1700s, which seems like a good stopping point for this installment. Tune in next week to see opera progress.

It’s one of the few genres that lasted for centuries, so there’s lots to talk about.

- Please note that the Suggested Listening clips are single arias from operas that might last a couple hours. You can find complete operas with full stage performances on YouTube.

Or better still: go to a live opera.

Suggested Listening – Full YouTube Playlist

L’ Euridice – 1 Prologo La Tragedia

Jacopo Peri0

1602

L’Orfeo – Vi ricorda, o boschi ombrosi

Claudio Monteverdi

1602

“La liberazione di Ruggiero dall’isola di Alcina” – Antri gelati

Francesca Caccini

1625

Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria: Act V, Scene 10, “Illustratevi, o Cieli”

Claudio Monteverdi

1639

Doriclea: Se ben mai non mi vide questa città (Doriclea lamento)

Francesco Cavalli

1640

Seelewig, Act I: Die güldene sonne schwebt über dem meer

Sigmund Staden

1644

Persée: Je perdu la beauté

Jean-Baptiste Lully

1682

King Arthur: “The Cold Song”

Henry Purcell

1691

Il Pirro e Demetrio: Le violette

Alessandro Scarlatti

1694

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

I’m not sure this style is my scene. I might just stick to watching Cher be entranced by it in “Moonstruck.” But I do appreciate the primer, in the event I ever change my mind.

Thanks for the thought-food, and for these great early selections.

Wow. That Neil Balfour really went all in on his performance of the Cold Song. Ironically, he was probably very hot while singing that!

One of my favorite takes on that one is a more gender fluid one by Klaus Nomi:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HOABpnJXJAg

Like Chuck, I’m not really into opera. There are select songs that have grabbed me, like The Cold Song, Au Fond de Temple Saint, and various bits from The Marriage of Figaro.

And when I was preparing for the Wagner piece I recently wrote, I heard a bunch of brilliant music–and also the “squillos” and other elements of operatic sound terrorism. Part of that is Wagner in particular, who took the excesses of opera to unparalleled extremes. But I feel roughly the same way for Mozart’s operas, and he was a composer of exquisite balance.

I do love the opera-adjacent Messiah by Handel, perhaps because the sprechgesang is kept to a minimum, and so it just feels like a collection of bangers.

But you’re right, I haven’t yet seen an opera performance live. Given that orchestras sound so dramatically different in a live setting, I fully accept that the strong lead vocalists may get the short end of the frequency stick in recordings. I need someone to insist I go to one those. One of the shorter ones. And maybe drag me there.

Which one did you see, by the way?

Klaus Nomi is one of a kind. I hadn’t heard his version of “The Cold Song” but his voice always astounds.

Operatic sound terrorism! Hilarious.

My employer gives away tickets to various events so I’ve been lucky enough to see a few operas. “Pagliacci” and “Madam Butterfly” come to mind.

No kidding – so when someone says they’ve been trained as a classical opera singer, they really mean they trained their throat muscles to work a particular way. I always thought it was just a different way of controlling their breathing or something.

I’ve always felt opera was ridiculously pretentious and totally not for me. But as I’ve gotten older I can appreciate it’s uniqueness as an ancestor of the Broadway musical (which I still am not a fan of personally, but I don’t ever want to diminish its impact on musical fans).

And I totally understand you statement Bill that opera needs to be experienced live. Opera is supposed to be multi sensory. The more, the better as far as that community is concerned!

Excellent primer so far, thank as always VDog!

I will consider this my entry point into the world of opera, as I’ve gotten no further into it than Looney Tunes’ ‘The Barber of Seville.’ Thanks, Bill. Also, what do you have to do to become a chamber boy?

I’m not sure but I think you have to show competence with chamber music. Or chamber pots. Something like that.

Ah. Thanks. It sounds much more illicit than it actually is.

The teaser graphic for today almost included a “kill the wabbit” joke.

And now that I think of it, it probably would’ve been funnier…

Kill the wabbit?

https://youtu.be/_lvsp_yTOw8

One year at Glastonbury the English National Opera appeared on the main stage, first thing Sunday morning performing some of the greatest hits of the Ring Cycle. We stumbled out of our tents for breakfast accompanied by an hour of Wagner, it might not be my thing but I didn’t want to pass up a chance to see something I’d never normally be exposed to. It was impressive but not so much that I wanted to commit to shelling out for a standard opera experience. Not sure it would replicate the magic of being in a field, early in the morning while eating a bacon sandwich.

When I was younger it was very much a case of the class aspect getting in the way. Opera was for the wealthy. It’s still seen that way here that it’s for a certain class of person so other than occasional use in films and TV ads it can be ignored by most of the population. I’m not so blinkered that I would let class distinction put me off now but it definitely suffers from an image problem in being an elitist enterprise.

In the states, I think most people subconsciously equate a British accent with intelligence and sophistication. I’ve read that this inclination goes back to colonial times.

Which begs two questions, is there an equal effect or example in the UK, and also, what happens when you all hear an American accent?

(I have a personal experience story on the latter.)

I can state with 100% confidence that a British accent is not a signifier of intelligence.

It’s more that the opposite is in effect here. There are certain accents that are stereotypically seen as signifying lack of intelligence or other negative connotations such as scouse (Liverpool), geordie (Newcastle), Brummie (Birmingham). There is something call RP; Received Pronunciation which isn’t so much an accent but is more a sign of being educated to talk in a way designated as the correct way of speaking. Its not as prevalent now but its what tv and radio presenters, particularly on the BBC, would be expected to adopt in the past.

As for what happens when we hear an American accent there’s no quick and simple response to that. In the same way that we’re quick to judge ourselves based on accent the same happens on an international level. Being diplomatic, it depends in part on who is in power. While Bush Jnr was in charge it was liable to induce feelings of superiority. With Obama in charge it was much more positive. With Trump…..maybe best to leave that unsaid.

My goal was to stay in academia, so I strived to speak perfect English. When that didn’t pan out, I worked at a place where certain words would elicit blank stares or laughter. The self-conscious eradication of my regional dialect and accent suddenly became a problem. I was totally immersed in my major. That’s why I regularly experience culture clash. I’d get this response when I’d use “pidgin English”.

“No act.”

It’s funny you say that – I always wondered if there could be an alternate universe where pompous British shows and movies portrayed the elite as having a Brooklyn accent or were Cajun. Or maybe from Wisconsin.

😆

Mmmmm… bacon sandwich….

We’re not so intellectual here to call it class. We call it white collar vs. blue collar, but it’s very definitely class, and opera has that rich-people stigma. We think opera ticket prices are high but we’ll shell out more for the next big rock tour coming through town.

I don’t think I’ll get into ballet in this series, even though there’s a lot of music written for ballet, but add “Carmina Burana” to your list of events to see. Remarkable music.

I don’t know about the ballet but the sound of O Fortuna is redolent with the smell of Old Spice.

https://youtu.be/6rbZr7YoqK0

“The mark of a man?” Old Spice? All the grandiose orchestral music in the world couldn’t sell that line.

Now if it had been Canoe…

I may or may not have saved up my paper route money in junior high school, and rode my bike to the Rexall to buy a bottle of Hai Karate in preparation for the Saturday night dance.

In a similar vein, when my family and coworkers heard I was going to France, their reaction was “Ooh la la, Mr. Fancy Pants rich guy…”

Not realizing that they spend four times as much money on mediocre-to-decent food in DC whenever they go out, and are shelling out the same money on their trips to Disneyland as I did to travel across the globe. You do you by all means, but forgive me for thinking I got the better deal for my dollar!

A confession: If/when I get asked “what music do you like,” my short answer is: “Everything but opera.”

Admittedly, I’ve never seen an opera in person. Maybe I’d enjoy the experience, but that stereotypical ultra-wobbly operatic singing style presents a high hurdle.

I didn’t expect to learn of an overlap between jazz and opera, but that “head-improv-head” structure definitely qualifies.

Thanks for another interesting entry!

Bill,

You took something I had little interest in (I’d never been to one, obviously), and created a little rabbit hole that makes me want to explore it further.

Damn you!!!

Strangely, I got into opera by listening to it recorded long before I saw an opera performed. In hindsight, though, you are absolutely correct that seeing an opera performed is much preferred.

OK, if I’m being honest, I got into opera from pieces popping up in movie soundtracks – it’s not like I was hunting opera CDs down at Tower Records.

There’s a great EMI / Angel album called “The Movies Go To The Opera” which was my gateway drug, as was the soundtrack to the movie “Aria”.

I wish I could say that I’m different, but I just have a difficult time with opera. My first experience with one was bad. I went to see Porgy and Bess, Gershwins’ operetta. For as lovely as some Gershwin songs are, I really wasn’t entranced with those songs…and the singing? There was so much vibrato that I often couldn’t even tell they were singing in English! It was a real disappointment.

Years later we saw Mozart’s The Magic Flute. I think that it’s a rather light-hearted opera compared to some. It was much better. But it still was a flex to try to enjoy it.

Would I go to an opera again? Only if I knew ahead of time that it wasn’t too heavy. But maybe. But I agree with you, V-dog…there are a LOT of kinds of recorded music that I would rather listen to than opera. (Like…most of them). Nothing more disappointing than wanting to hear some random classical music, turning on the classical public radio station and they’re playing an opera. Ugh.

It’s better live but it’s still not for everybody.

Not everybody can. Many people are literally incapable controlling their throat muscles that way.

I heartily concur that opera is best experienced live. If you do listen to a recording, you’re better off with vinyl. The compression required for CDs and streaming makes it a much worse listening experience.

I never paid much attention to opera until I won a pair of free tickets to a production of Don Giovanni in the late 80’s and invited a girl I was trying to impress. I was mesmerized. Her, not so much. Might have gone better with surtitles. She kept asking me what was going on in the story, as if I knew any more Italian than she did.

It took awhile to get through all the music samples.

Okay.

I’m ready to do the Luciano Pavarotti deep-dive.