From a text conversation with my friend Laurel when I told her I was writing about opera:

Mozart was indeed cool.

Very cool. But I encourage you to not treat Laurel’s statement as factual. Don’t go quoting her in your Music History term paper, or anything.

We’ll get to Mozart, but let’s go over some basic stuff that I left out of Part 1.

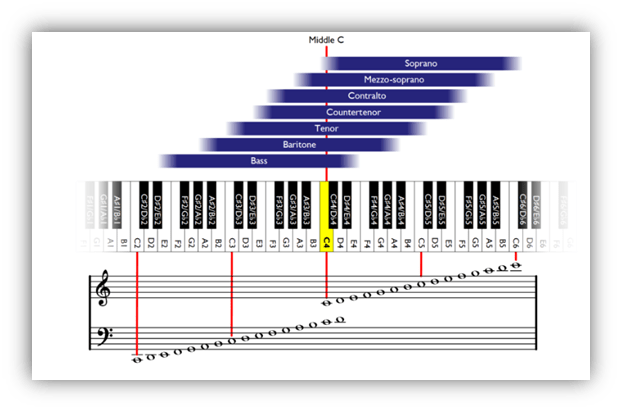

Opera uses many voice types.

Voices are categorized based on the range of pitches each singer can hit. For men, from low to high, there are bass, baritone, tenor, and countertenor. For women, it’s alto, mezzo-soprano, and soprano.

All of these ranges include middle C, though it’s at the high end for the bass voice type and the low end for sopranos

Opera composers specify each character’s voice type. You don’t put a soprano singer in an alto role because she won’t be able to hit the low notes. Voice types don’t matter as much in genres like rock or gospel, but in opera, the composer selected the voice type to match the character’s persona.

The hero is usually a tenor.

The villain is often a bass.

There’s also the delicate issue of castrati. These were young boys with beautiful high voices, in the soprano range. To keep those voices high and youthful, a “surgeon” would cut the ducts connecting the testicals to the rest of the body, and the testicles would shrivel away.

The child’s body no longer had a source of testosterone, so puberty never arrived and the voice never dropped.

There were many other physical effects and the boys’ lives were never the same.

The available anesthesia was opium, and 20% of castrati didn’t survive the procedure. It’s a disturbing practice that ended only in the 1870s, so late that we have a recording of Alessandro Moreschi, one of the last castrati.

These boys often didn’t have a choice in the matter. Their families thought it was a way to make money. A very few went on to become famous singers, but most had to sing in the streets or engage in sex work (with both men and women) to make ends meet. Unable to have families, many died alone.

As voices can be categorized, so can opera itself.

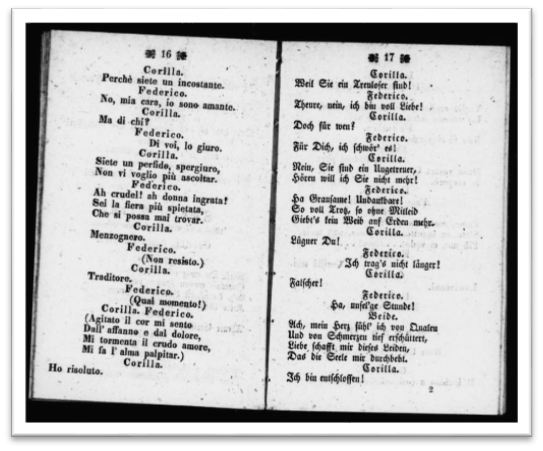

In Italy, there was opera seria and opera buffa.

“Seria” is Italian for “serious.” And it’s the form that spread across Europe, except for France who preferred to do things their own way.

Opera seria became more about vocal skills than about the stories’ plots. The bel canto technique focuses on the sound of the voice with little regard for the meaning of the lyrics. “Bel canto” means “beautiful singing” in Italian, and it’s the open throated sound we stereotypically associate with opera.

German and English composers often used Italian libretti, which their audiences may not have understood. Even if they did, the stories were secondary to the music and singers’ talents.

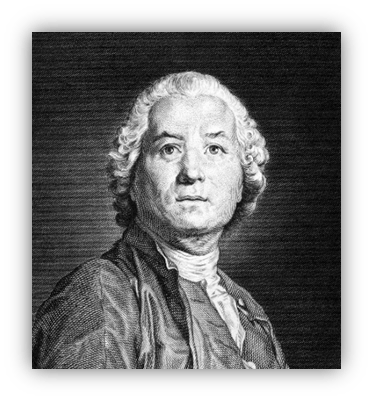

Christoph Gluck and other composers thought the opposite. The music must serve the story and not the other way around. Gluck’s “Orfeo ed Euridice” is a good example of his work. The music is simpler than most opera seria, and not at all showy.

Opera buffa, on the other hand, is about everyday people rather than gods. It’s usually comedic, often a love story with wacky misunderstandings and complications, but always with a happy ending. Opera buffa is the musical equivalent of rom com movies, though it sometimes uses crass humor and innuendo.

Unsurprisingly, Mozart was a fan.

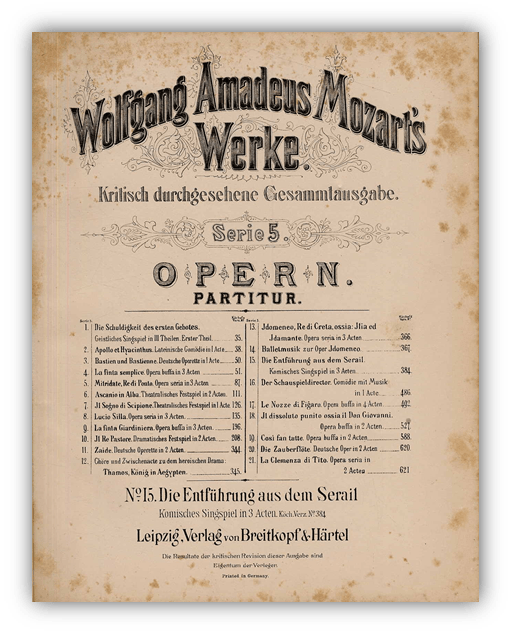

He and his various librettists, notably Lorenzo Da Ponte, wrote a couple opera seria.

But most of his works were opera buffa. “Don Giovani,” “The Marriage of Figaro,” and “The Magic Flute” are all opera buffa, and good starting points for opera newbies.

German composers gave a name to the sing-speaking way to handle recitative text. They called it singspiele.

Not only did Mozart use it, but so did the later German composers he influenced: Beethoven, Schubert, Wagner, etc.

I mentioned that France had their own variations of opera, and they were tragedie en musique and opera comique. Tragedie en musique was often about mythological characters but, unlike opera seria, didn’t necessarily have tragic endings, despite its name. However, it had to be noble and sophisticated.

Opera comique is the French version of opera buffa, except it didn’t always have a happy ending.

Funny things may have happened throughout the story, but audiences couldn’t see the predictable happy ending coming because it might end otherwise.

In both subgenres, the French wanted their men to sound like men, so there were no castrati. They also liked each act to end with divertissement, a big spectacle with lots of people on stage and huge choruses.

Henry Purcell had been the star opera composer in England, but he died in 1659 at only 36 years old. Opera’s popularity faded without him and didn’t rebound until Thomas Arne came along. Arne’s first opera was “Rosamond” in 1733 He kept working until his death in 1778. He wrote mostly comic opera.

George Frideric Handel, on the other hand, wrote in the Italian style of opera seria despite being a German-born naturalized British citizen.

However, he had a stroke in his early 50s. He recovered in a few months and looked at life differently afterwards. Rather than write for the aristocracy, he directed his music to the middle class. He was a composer of the first order, regardless of what style he set his mind to.

Back in Italy, Gioachino Rossini wrote 39 operas and a lot of other music before retiring at the peak of his popularity when he was still in his 30s. We know him today for “The Barber of Seville,” and “William Tell,” the overture of which was used as the Lone Ranger theme song. He was a fan of grand opera, which can be described in three words: big, big, and big.

Grand opera usually used historical or otherwise true stories and they were extravagant productions with lavish sets, enormous casts, and powerful music.

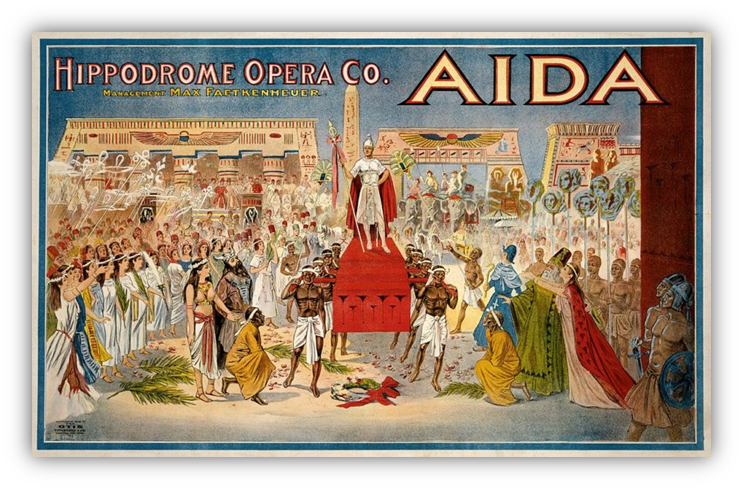

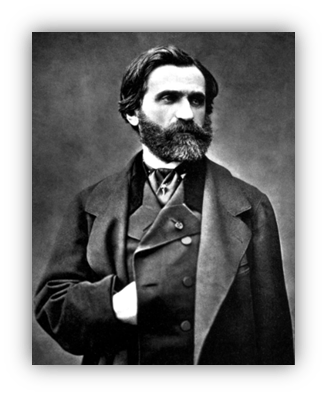

Like Rossini, Giuseppe Verdi loved grand opera.

His 1871 work “Aida” is a great example. In Act II Scene 2, there’s a Triumphal March across the stage. Not only are there dozens of actors involved, but there’s also a parade of animals, including an elephant. Some lesser productions use puppets or mechanical animals, but if you’re going to do it right, use real live elephants, camels, and lions.

And you thought Parliament/Funkadelic’s spaceship was over the top.

Verdi also began to blend arias and recitatives so they flow into each other more naturally. This can be heard in works like “Rigoletto” and “Don Carlos.”

German Richard Wagner was different from most composers in that he wrote both the libretti and the music. He believed in what he called gesamtkunstwerk, the idea that all the arts should be included in the same work. Music, writing, dance, the artistry of painted sets, etc. To achieve this, he built his own theater in Bavaria.

Wagner used big orchestras and casts, and his works could be long. “The Ring Cycle” is famous for its length. It’s made up of four operas that together last 15 hours.

In addition to his musical output, he wrote essays about where music, politics, and culture should be headed. His opinions were influential but controversial, especially his anti-semitic views.

Towards the end of the 1800s, the verismo style developed. Verismo strived for realism, telling real, even gritty, stories of the human experience. As Phylum Of Alexandria recently pointed out, this kind of realism was happening in the other arts at the same time. There wasn’t as much spectacle as in grand opera, the dialog was more natural and the heroes were unconventional characters often dealing with poverty, injustice, or just humble rural life.

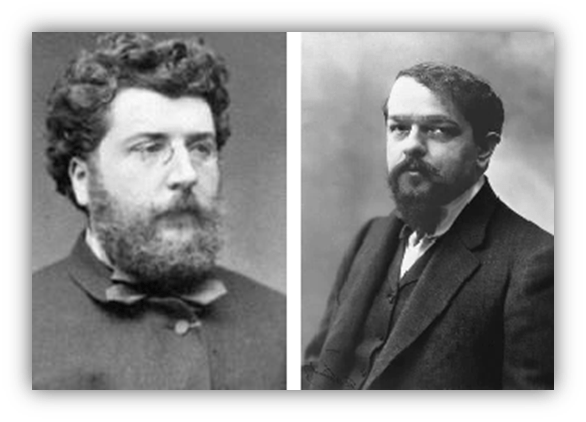

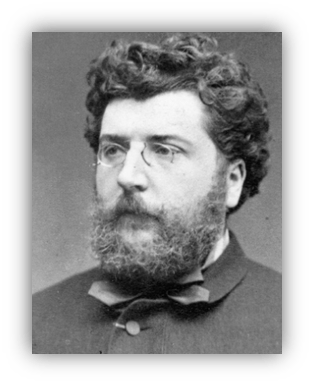

Like Verdi and Wagner, French composers began blurring the lines between recitative and arias. Georges Bizet and Claude Debussy both did this. Also like Wagner and the verismo movement, they used realism in their stories.

However, where Wagner used long arias, Debussy in particular used long recitatives. And where Wagner made story secondary to the music, Debussy used the orchestra for atmosphere more than anything else.

We haven’t talked about Russia yet. Mostly because they loved Italian opera so much they didn’t begin to develop their own style until the 1800s. Mikhail Glinka was one of the first composers to add Russian elements to opera. He included folk music and dance, and emphasized nationalism.

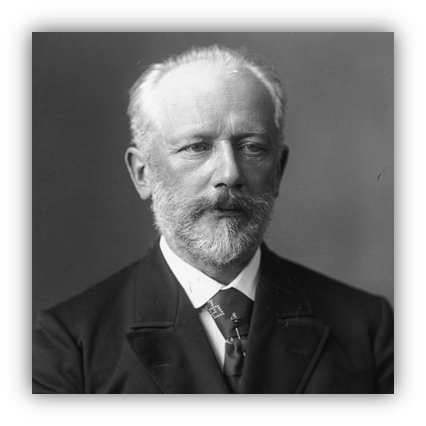

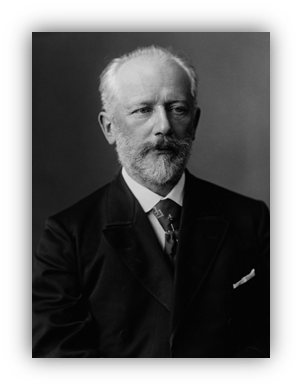

Later, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky used Russian folk melodies, too.

In the 1900s, opera developed a movement called modernism.

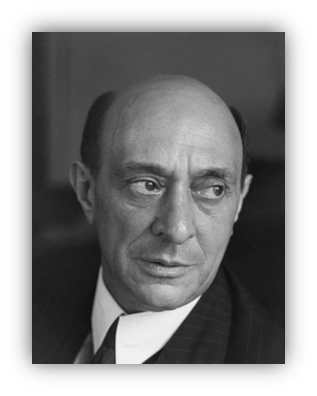

It tried to free itself from conventional harmony and meter, often to the point of being atonal. Modernists sometimes wrote in odd time signatures and intentionally used dissonance. Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, and Anton Webern used the twelve-tone scale, meaning they used every note on the piano.

Twelve-tone pieces, therefore, don’t have a tonal center. They’re in no key and every key at the same time.

This is hard to listen to, of course. And neoclassicism was a backlash against it. Englishman Benjamin Britten and Russian Igor Stravinsky used diatonic harmony, meaning picking a major or minor scale and sticking with it. Neoclassicists brought back polyphony from the baroque period, as well as its goals of balance and structure. It was a conscious return to the forms of earlier periods, but with a modern sensibility.

Which brings us to the United States.

A new country, it was late to the opera game but 20th Century composers like George Gershwin and Leonard Bernstein wrote English operas (meaning with spoken rather than recitative dialog) in addition to the musicals and jazz songs for which they’re better known.

We should note that when Gershwin staged “Porgy and Bess” in 1936, it was with an all-black cast.

Its performances were the first with integrated audiences at Carnegie Hall.

Less than one hundred years ago.

Speaking of musicals, they’re another descendant of opera, and perhaps worthy of coverage here. Stay tuned.

That’s an extremely brief overview of opera, a genre that has lasted for centuries. It may continue for many more.

The main takeaway should be that you need to go see one or two or three.

Even small cities have opera companies or touring troupes that come through town. Make the effort to get tickets. That’s really the only way to experience it.

Though viewing a full opera on YouTube is a good start.

Suggested Listening – Full YouTube Playlist

Orphée et Eurydice – J’ai perdu mon Eurydice

Christoph Willibald Gluck

1774

The Magic Flute – Queen of the Night

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

1791

Il Barbiere di Siviglia: “Largo al factotum

Gioachino Rossini

1816

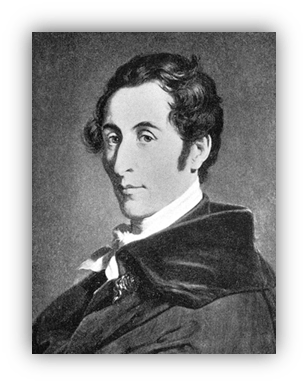

Der Freischütz – Huntsmen’s Chorus

Carl Maria von Weber

1821

Life for the Tsar – Forest Aria

Mikhail Glinka

1836

Rigoletto – Cortigiani vil razza dannata

Giuseppe Verdi

1851

Carmen – Habanera

Georges Bizet

1875

The Queen Of Spades – Ya vas lyublyu

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

1890

Oedipus Rex – Jocasta’s Aria

Igor Stravinsky

1927

Porgy and Bess – Summertime

George Gershwin

1936

https://youtu.be/q2o-VvaJiao

Peter Grimes – Now the Great Bear and the Pleiades

Benjamin Britten

1945

Moses und Aron – Das Goldene Kalb und der Alter

Arnold Schoenberg

1957

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

You told the sad tale of the castrati with such compassion, Bill. Thank you.

Wow — I can’t figure where you’ll go from opera. But trying to figure it out is half the fun!

Have a good weekend.

What’s with all those composers with their hand in their jacket? I’m guessing they kept a sandwich in there. Early photography not being quite so instantaneous, always pays to keep a snack to hand.

Rossini wrote 39 operas and retired in his mid 30s – Way to go at making the rest of us feel inadequate.

My main takeaway is that if I see one opera it should be Aida. As long as its with the full zoo. Or maybe that’s an idea for a zoo to branch out.

I’ll be on a flight to Italy at the unseemly hour of 6am tomorrow morning (11 year old daughters idea is that if we’re getting up before 3am why don’t we just stay up all night? Hmmm, no. Though we might be at the hotel before they finish serving breakfast). My Italian is limited but I’ve got a few extra phrases to use thanks to this. Just have to engage the waiter in a discussion opera rather than my order to make them work.

Being American, I thought they were reaching for their guns. While we think only Napoleon kept a hand in his vest, turns out it was a common practice. I don’t know why though. That’s probably a topic for an article here.

Have a great trip!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hand-in-waistcoat

Interesting. I’ll have to do it when I sit for my next portrait. But how, one wonders, does one slip one’s hand into one’s t-shirt?

If you go under, you’re exposing your belly. If you go over, your stretching the neck. Neither would be particularly flattering.

May need to bring a flannel button-down shirt to avoid any permanent damage or embarrassment…

Through the sleeve, making a chicken wing?

It’s the 18th and 19th century version of NFL football players holding on to the neckline of their pads as they stand on the sidelines.

So basically it’s a portrait trend, like the more recent “selfie duckface.”

“Le quack, mon amie…”

Have never done that in my life. Too tall for any waistcoat.

Dunno NoB, you could start a new fashion trend of men showing underboobs via too short waistcoats….

This one always works!

https://translate.google.com/?sl=it&tl=en&text=Vorrei%20ordinare%20le%20linguine%2C%20per%20favore.%20Ma%20prima%3A%20godetevi%20la%20mia%20speciale%20interpretazione%20di%20%22Prisencolinensinainciusol!%22&op=translate

Have a wonderful trip, and try to check in if you can with some photos!

The fandom of the opera is there…inside your mind!

I kid, I kid. And regardless of how I feel about the music, it sure is interesting to read about.

We all know that music theory is not my forte (i.e., it’s my piano?), so thanks for explaining 12-tone serialism. If I had to explain Schoenberg’s opera, I’d say “Sounds like Wagner, but with the variance bandwidth kernel turned all the way up.” So, the rest of the world thanks you for your effort.

Phylum, coming on strong with the operatic musical punnies this Friday morning!

It is rather fascinating, considering how opera is generally dismissed by many as being too pompous or something they have zero interest in, just how familiar we truly are with alot of operas.

And not just thanks to Loony Tunes. But I will be the first to raise my hand and say that’s where I first noticed specific opera selections!!!

It’s funny, I associate Mozart as a classical composer, I’ve never considered him to be an opera composer. That’s kinda trippy to wrap my head around that realization.

Anyone else suddenly get vibes of Monty Python’s Lumberjack Song when watching the Huntsman’s Chorus clip???!

Thank you as always for educating us in the many sides of music, VDog. Nom-nom-nom!

What a dichotomy: Looney Tunes and opera (at least as opera is represented in society these days Dutch)!

I may have seen an opera in my lifetime, but it definitely isn’t my cup of tea. Reading about it thru V-Dog’s eyes was more my speed…much like baseball had become before this year’s rules changes.

I had a conversation years ago with a guy I didn’t know well. He figured out we were about the same age and said, “Do you know what’s wrong with kids these days?”

I thought, “Oh boy, here we go.”

But he surprised me by saying, “They didn’t grow up on Looney Tunes.” Then he explained that, not only do you learn about classical music, you get all sorts of cultural references. More importantly, every character has distinct personalities like the ones you’ll encounter in real life. We all know tough, cool guys like Bugs Bunny, egotistic cowards like Daffy Duck, people who never stop talking like Foghorn Leghorn, and so on.

“Everything you need to know about life is in Looney Tunes,” he told me, and I’m inclined to agree.

And Looney Tunes is funny. My favorite part of Robert Smeigel’s Disney sendup is when one of the kids tells Mickey Mouse: “You’re supposed to be funny?” And the crestfallen look on Mickey’s face, sagging shoulders. Also, South Park pointed out how Mickey laughs at his own jokes.

Going through all of my throwback reviews on the mothership, it’s amazing how many of those old popular songs are referenced in old Looney Tunes cartoons!

And over the years, Foghorn Leghorn has become my favorite Looney Tunes character. I just love it when he won’t shut up.

Bill, that was an impressive sprint to the finish line, covering a LOT of territory in two reasonable length columns! Definitely a learning experience for me many times over. Thanks for sharing!

As a basso profondo, I appreciate the vocal breakdown immensely, and your account of companies’ lifelong mistreatment of castrati was deeply moving. Great article, Bill.

One point that I hadn’t known about until recently concerns voice “types”. In German classification, it seems to also be divided into what are known as fächers — a combination of range, weight and colour that determines which roles suit them best.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fach

Wow, that’s fascinating. I didn’t stumble across that in my research. Thanks, NoB!

“The villain is often a bass.”

It’s just not fair, Bill.

I suspect that Tom, had he written a column about the no. 1 operas, would give The Magic Flute a review similar to what he gave ‘Penny Lane’: ‘indulgent and borderline unpleasant’; ‘jumps around consistently, never content to sit still’; ‘a showoff move without much behind it.’ He doesn’t appreciate that kind of showmanship, methinks.

I don’t know about the rest of you:

But I gotta love a guy who remembers the capital crime of the “6/10” that was committed on October 5, 2018.

Never forget.

Ooohhh, that one sticks in my craw. Never forget!

Have you seen Ingmar Bergman’s version of The Magic Flute?