All four of my grandparents were French-Canadian.

My parents speak French fluently but they didn’t teach us kids.

There’s a prejudice against the French, still, in northern Maine and the Maritime provinces of Canada.

Which is odd because there are so many French people there. Due to that prejudice, parents don’t teach their children the language, and the French influence has been watered down to the point where people actually say things like, “I’m not French but my parents are.”

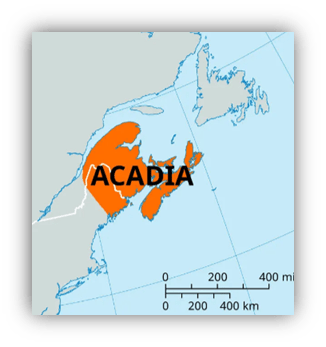

In the winter when the leaves were off the trees, I could see the Kennebec River from the house where I grew up. The Kennebec is the western edge of the region formerly known as Acadia. It extended all the way east to Nova Scotia and north to Quebec, though exact borders were never defined.

The settlers there were mostly from southwestern France. They got along well with the native Americans, especially the Mi’kmaq, and built dikes and dams to irrigate the farmland they developed.

They wanted to live off the land, and not much more than that.

Just a good, basic, life. They had no time for politics or expanding any country’s claim to the new world.

That’s why Acadia’s borders were never charted out. It just didn’t matter to them. It certainly wasn’t worth taking up arms for.

They tried to remain neutral as the French and English fought over who would rule the area. Again, it wasn’t worth taking up arms for. When they refused to sign loyalty pledges to England (because they wouldn’t have signed pledges of loyalty to anyone), the British expelled them.

That’s the nice way of putting it.

It was ethnic cleansing.

From 1755 to 1764, the British deposited about 14,000 Acadians in France, England, the American colonies, and various Caribbean islands. Some escaped to French-speaking Quebec. The British broke them up into these smaller groups so they couldn’t band together and become a military or political force.

Conditions weren’t much better than on the slave ships of the day. About 3,500 died en route.

Some fought back, but since Acadia had no borders or army or much of a government, any acts of resistance were spontaneous and local.

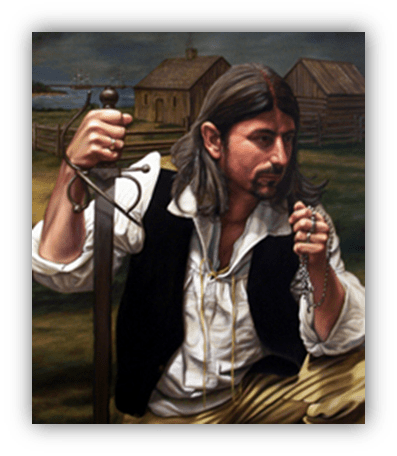

Joseph Broussard, who was also known as Beausoleil, was the closest thing they had as a leader. He did indeed take up arms to fight the British and had several successes, but was eventually captured and imprisoned.

When Beausoleil was released after the Seven Years War in 1764, he led a group of hundreds; first to Haiti,and then to Louisiana.

Louisiana’s climate is nothing like Acadia’s. So they had to relearn their farming techniques, and they adapted very well. Eventually, the word “Acadian” was shortened to “Cajun.”

It was first meant as a slur, but the Acadians embraced it. Other than the farming and the name, their culture really didn’t change very much.

Again, they befriended the locals, both native and immigrants. Creole people were already there, too.

It’s hard to get a concise history of Creole history. They are a loosely defined, multi-cultural mix of native people and the Europeans who colonized their regions.

There are Creoles around the world wherever Spain, England, France, Portugal, or other external force mixed with natives.

The Creoles of Indonesia, for instance, are a mix of natives and Dutch.

In Louisiana, natives from North and Central America and the Caribbean intermarried with French and Africans. The Africans could be slaves, or free people of color. As such, Louisiana Creoles can be European pale or African dark, but they mostly check the “African American” box on government forms, as a matter of pride.

Creole languages are variants of the colonizers’ languages. Interestingly, the Creole spoken in Louisiana and the Caribbean is based on metropolitan French, but folks from France can’t understand it. However, the French and Cajuns can understand each other, and the Cajuns and the Creoles can understand each other.

We shouldn’t conflate Cajun and Creole. They are similar but distinct peoples, with different languages and cultures.

Likewise, their music is similar – but not quite the same.

Both Cajun music, and the Creole music known as Zydeco are influenced by the cultures around them.

Cajun is Acadian French folk music…

and Zydeco is Afro-French folk.

Over time, both have evolved and incorporated elements from various other genres, like African rhythms. Yet they still maintain their cultural roots, though Zydeco is more likely to adopt new contemporary trends.

Zydeco gets its name from “les haricots,” which is Creole French for “snapbeans.”

The phrase “les haricots sont pas salés” means ”snapbeans without salt.” In other words: times are so hard, we don’t even have salt for our beans.

Both genres often utilize syncopated, energetic beats. Zydeco, in particular, has a strong influence from African and Creole rhythms. This influence is also present, though to a lesser extent, in Cajun music.

Zydeco tends to use staccato, or short, notes. Cajun music usually plays longer notes with fewer rests between them. When played at standard fast tempos, however, this difference gets pretty subtle.

Cajun typically has a 2/4 time signature and a steady, upbeat rhythm. Zydeco often incorporates a syncopated, infectious rhythm with a 4/4 time signature. It also stresses the backbeat it got from rock & roll.

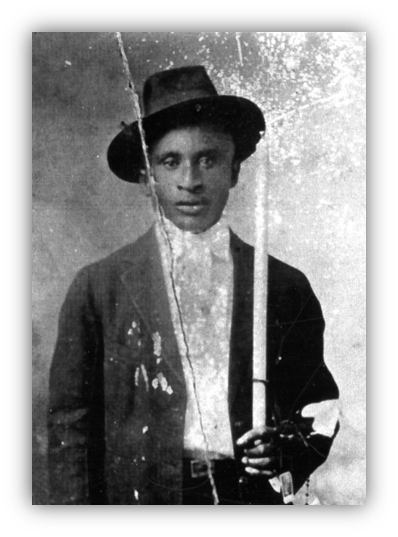

Cajun lyrics are sometimes in English and Zydeco sometimes uses the Creole language, but French is prominent in both. Amédé Ardoin, for instance, was the first black Cajun recording artist, and he only spoke Cajun French.

Cajun songs are mostly about love, community, life in the country, and the struggles of the Acadian people. Zydeco lyrics cover a wider range of topics, including personal experiences, relationships, and partying.

And it’s always a party. Both genres are primarily dance music. The fun, upbeat rhythms are great for festivals, social gatherings, and dances.

Cajun dancing includes the two-step, the waltz, and the jitterbug. Zydeco dance is more free-form, with few prescribed steps. Dance how the music moves you and, as the saying goes, “Laissez les bons temps rouler:” “Let the good times roll.”

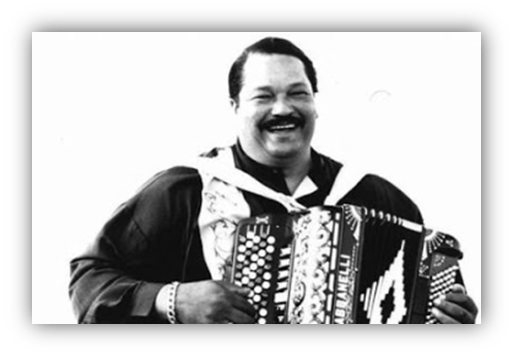

The accordion is a main instrument, though Cajun tends to use the button accordion and Zydeco uses the piano accordion, meaning it has a piano-like keyboard. While the piano accordion can play in any key, button accordions are limited.

Some have as few as eight buttons, which play the eight notes of the major scale.

So if the instrument has only, say, the C major notes, it can play songs in C major, its relative minor key of A minor, and G major with a flattened seventh. To play in other keys without getting into jazz modes, the player would need a second accordion set to a different key.

Cajun instrumentation tends to be sparser and with fewer musicians. A trio might use button accordion, acoustic guitar, and triangle.

In a classical orchestra, the triangle is suspended on a string so it can ring for a long time. In Cajun music, it’s held in the hand.

By hitting it with one hand and clenching and releasing with the other, a good triangle player can create intricate rhythms based only on differences in tone.

You’d be surprised how many different sounds you can get out of a triangle depending on where you hit it and how much pressure you use to mute it.

Zydeco bands, on the other hand, might have twice as many musicians: on piano accordion, fiddle, guitar, electric bass, a full drum set, and washboard. Washboard players will sometimes use an actual washboard but it’s more common to use a rubboard.

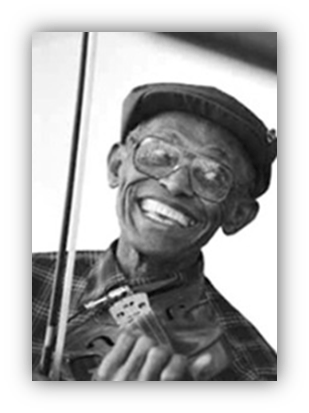

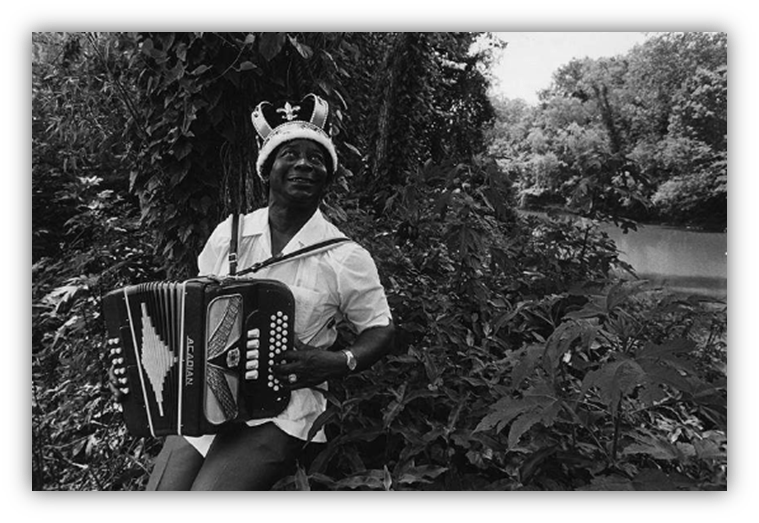

The rubboard was popularized by Clifton Chenier, who’s known as the King of Zydeco. It’s an instrument that hangs from the shoulders and is played by rubbing it with steel rods or silverware.

Chenier told the story that when was young and learning how to play the rubboard, he was rummaging around in a kitchen drawer, and his mother told him not to use her good spoons.

I don’t want to suggest that Cajun bands don’t use rubboards, or that Zydeco bands don’t use triangles. There’s a lot of overlap. Both use fiddle, for instance.

But Cajun is more likely to be stripped down to just a few instruments. It also tends to stick to acoustic instruments.

Cajun music maintains its cultural heritage while Zydeco has changed with the times.

Not only did it embrace the backbeat, it picked up R&B and blues and has recently started to include rap.

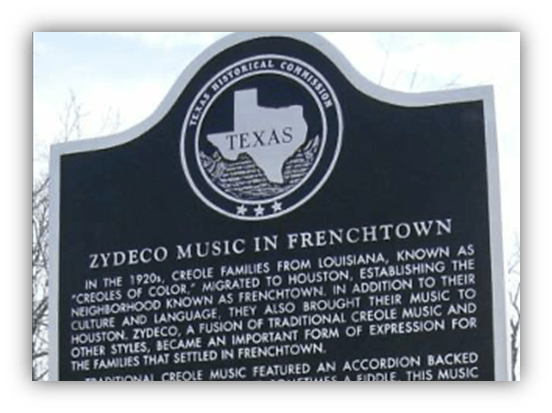

Southern Louisiana saw severe flooding in the 1920s and many people moved to what’s now called the Frenchtown section of Houston.

These days, Zydeco is more popular in Houston than Louisiana. Houston also has a big hip hop scene, so it’s not surprising that Zydeco has incorporated rapping.

Both Cajun music and Zydeco are deeply tied to community and social gatherings.

Festivals and parties are a way for people to come together, celebrate their culture, and enjoy music, dance, and food. Cajun and Zydeco are crucial parts of Cajun and Creole culture from southwest Louisiana to Houston.

It’s just not a crawfish boil without accordions and rubboards.

Laissez les bons temps rouler.

Suggested Listening – Full YouTube Playlist

Cajun

Allons à Lafayette

Joe e Cléoma Falcon

1928

Two Step de Mama

Amédé Ardoin

1930

J’Ai Été Au Bal

Iry LeJeune

1956

Parlez Nous À Boire

The Balfa Brothers

1973

Barres De La Prison

Canray Fontenot

1983

J’aime Grand Gueydan

Cajun Born (Johnnie Allan)

1989

Le Chanky Chank Francais

BeauSoleil

1991

Dans le magasin

Feufollet

2016

Zydeco

Mon Chère Bébé Créole

Dennis McGee

1929

Eh, ‘Tite Fille

Clifton Chenier

1965

The Louisiana Two Step

Rockin’ Dopsie & The Zydeco Twisters

1984

My Girl Josephine

Queen Ida & Her Zydeco Band

1991

One Kiss

Beau Jocque & the Zydeco Hi Rollers

1998

Let The Good Times Roll

Buckwheat Zydeco

2001

Call The Police

Boosie Badazz feat. Stephanie Mcdee

2020

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Thanks Bill, I learned a heck of a lot from this one. I passed by the Cajun/Zydeco portion of the World Music section at Tower Records so many times back in the early 00s, but only now did I actually hear the music.

The oldest versions of both styles sound like old country music, even some Irish folk. I like the relentless percussion in Zydeco; I wonder if Louisiana’s early racial codes allow blacks to have more instruments than other states.

And never would I have imagined that the name came from “les haricots.” But listening to the musicians actually say the word, it makes perfect sense.

You can hear it here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cZIrfedVem8

Good to have this back, so much fascinating insight and plenty of backstory to this one. Perfect mix of history, geography, sociology, musical theory and a bit of French. With a starring role for Britain in the introduction as the villain of the piece.

As a man of limited to no musical ability the one thing I thought I could probably handle is the Triangle. Now even that’s been taken away from me, turns out its way more nuanced than it looks.

The names of those performers are something else too (honorable exception of Dennis McGee); Rockin’ Dopsie, Buckwheat Zydeco and Boosie Badazz. These are names with character.

I looked for any Cajun artists named “Pythagoras,” to no avail.

I thought the same thing, JJ… I do think I could go to town (not very musically) on a rubboard!

I jokingly mentioned a few weeks ago when the band name tourney started that “I play a mean triangle”. Clearly I’m nowhere near in the same league as the Cajun musicians. Probably closer to Triangle Sally, although I still fall short on the choreography.

https://youtu.be/SrGJ8UyEkBw?si=GpOuuX-W5IkYfHAs

Fascinating read – great stuff.