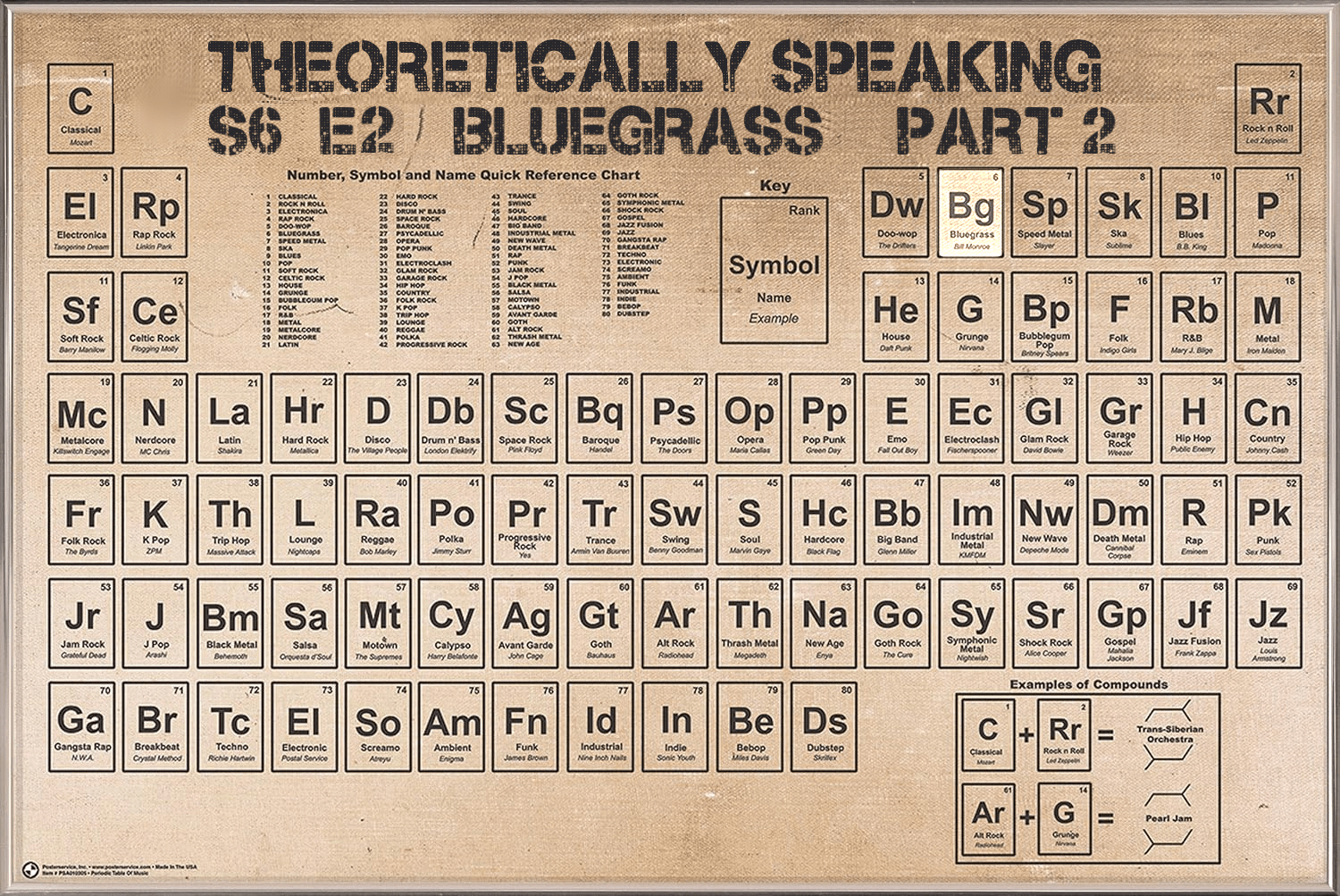

Part of Ska’s history is that it has had four waves.

Bluegrass has also had four waves, but we call them generations.

We covered the first generation, Traditional Bluegrass, and part of the second, the Folk Revival, in Part 1.

First generation Bluegrass is essentially Bill Monroe and his contemporaries inventing the genre.

It added instrumental virtuosity to the organic musicality of Old Time mountain music. Its popularity peaked in the 1940s and then faded in the 1950s as Rock & Roll took over.

However, the Folk revival of the 1960s built interest in all kinds of traditional music. Folk mainstays like Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie spread the word about Bluegrass. Traditional Bluegrass artists like Monroe, Flatts and Scruggs, and Reno and Smiley, found new audiences as they toured colleges and festivals, and new, young, artists picked up the sound.

This Folk Revival period through the 1960s is Bluegrass’s second generation. The sound didn’t change much, but the audience widened and the genre didn’t fade into obscurity.

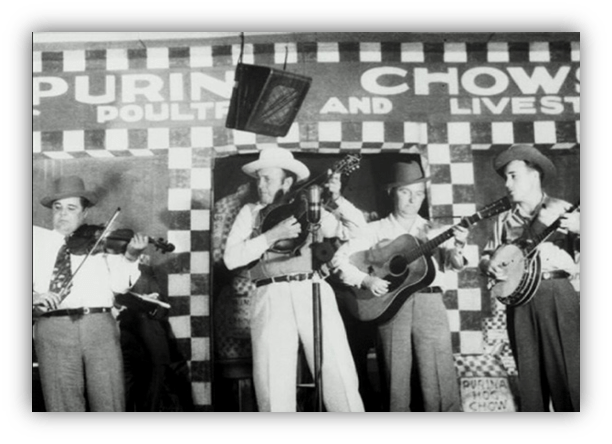

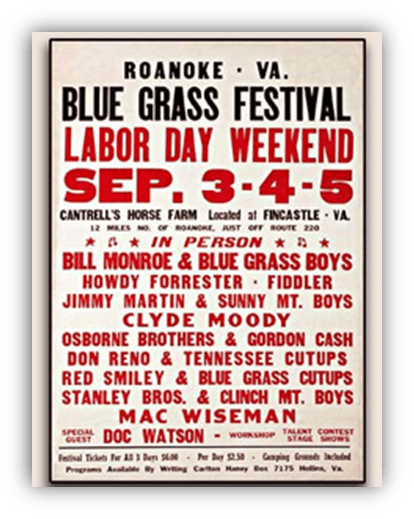

Multi-day music festivals were, maybe not invented but, reinvigorated by Carlton Haney.

He wasn’t a fan of Country or Bluegrass music, but he met Bill Monroe and the two took a liking to each other.

Monroe offered him a job booking shows for the Blue Grass Boys, and Haney resigned his position in a factory making car batteries.

He started booking other bands as he continued working for Monroe, and also managed Reno and Smiley, all the while not really liking or understanding the music.

He started booking package shows with several of his artists on the same stage.

In 1965, he and mandolin player Ralph Rinzler produced a weekend-long festival at Cantrell’s Horse Farm in Fincastle, Virginia. While days-long festivals have been around for centuries, this is seen as the invention of the modern music festival, predating both Monterey Pop and Woodstock by a couple years.

Rinzler went on to produce the Smithsonian Folklife Festival in 1967. That’s where, as I mentioned in Part 1, Charlie, Birch, and Bill Monroe reunited on stage in 1969. After taking a few years off due to the Covid pandemic, the festival will start up again in July of this year.

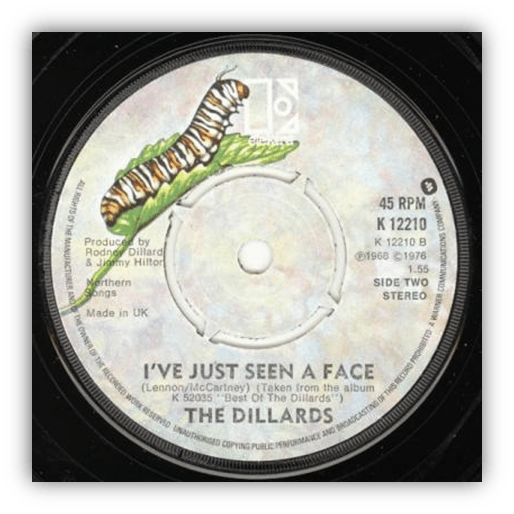

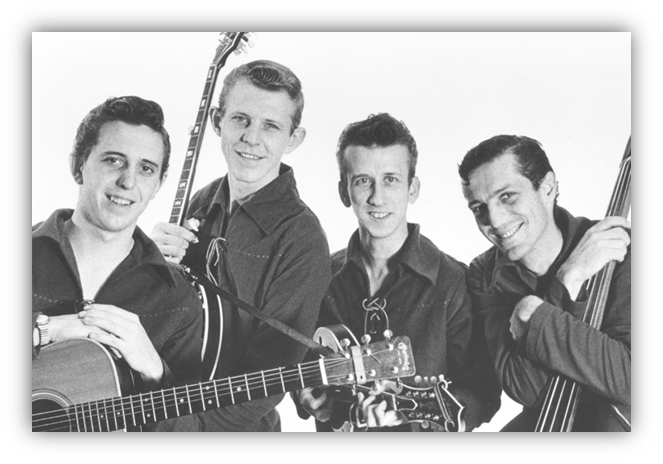

Musicians from outside Appalachia and the South got interested in the genre, like The Dillards from Missouri and The Kentucky Colonels from California.

The more successful Bluegrass musicians of this generation embraced change. They reached outside the genre to do cover versions of pop songs. There were a lot of Beatles covers.

The Dillards, by the way, would occasionally show up on The Andy Griffith Show as “The Darlings.”

The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band were also from California, and were fascinated by Country music and first generation Bluegrass.

Like Bob Dylan, Neil Young, and Linda Ronstadt before them, they went to Nashville to record their seventh album, and they asked their musical heroes to join them.

Bill Monroe declined.

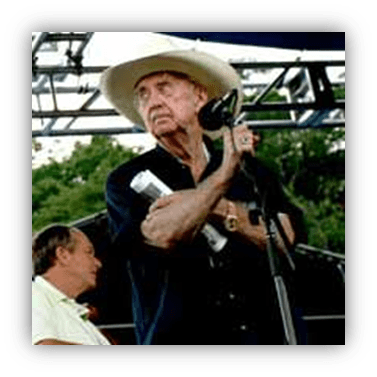

But Earl Scruggs, Doc Watson, Merle Travis, Roy Acuff, Jimmy Martin and “Mother” Maybelle Carter said yes.

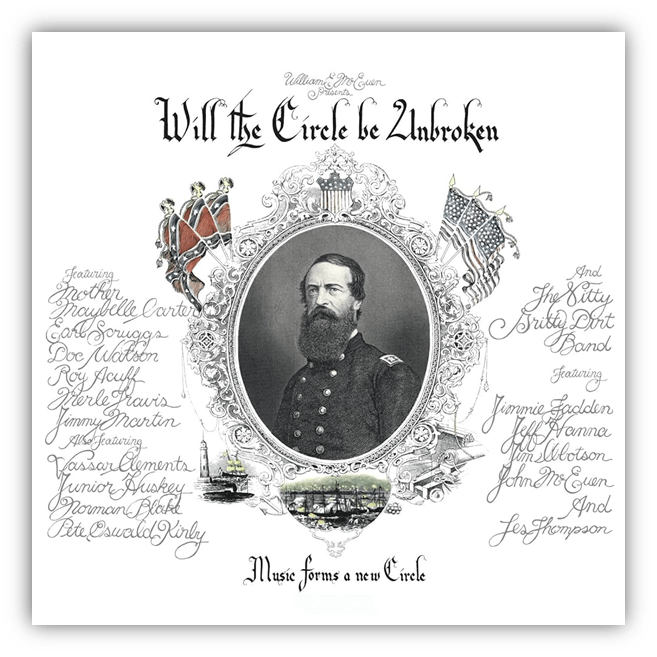

It became the three-record album Will The Circle Be Unbroken, named after the song from 1907.

The album was not only successful commercially, it renewed interest in these older stars and older music, and brought credibility to the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and other second generation musicians.

It hit #4 on the Country album chart, which is amazing for a three-record set – and is something not even Dylan, Young, or Rondstadt could do.

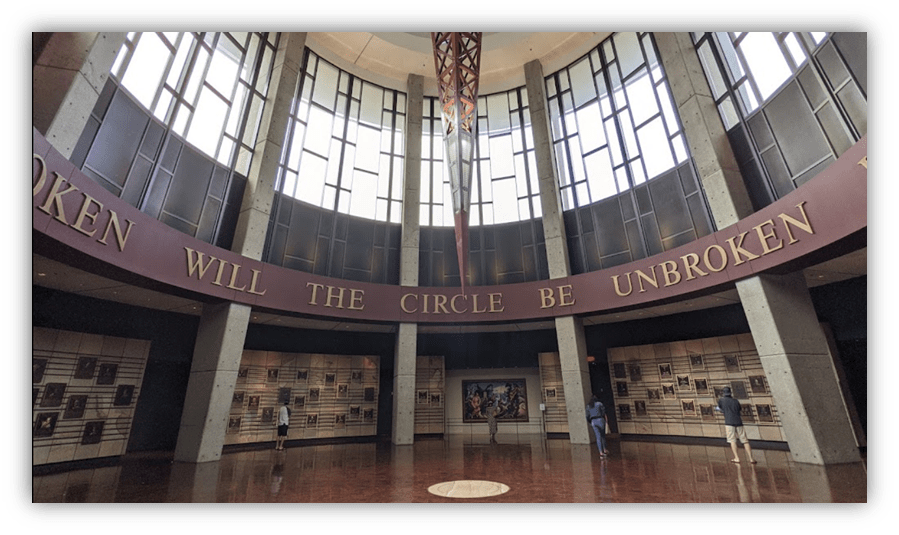

If you visit the Country Music Hall Of Fame in Nashville, you’ll see a circular room with the words, “Will the circle be unbroken.”

It signifies that music doesn’t spring into being spontaneously. It comes from its fathers and mothers, and will change with each generation. Notably, there’s no punctuation in that circular room, so you can also read it as “Unbroken will the circle be.”

The third generation of Bluegrass encompasses all of the 70s and 80s.

We call it ‘New Grass.’

It incorporated Rock and Jazz into the genre and expanded the repertoire with more covers and brand new songs.

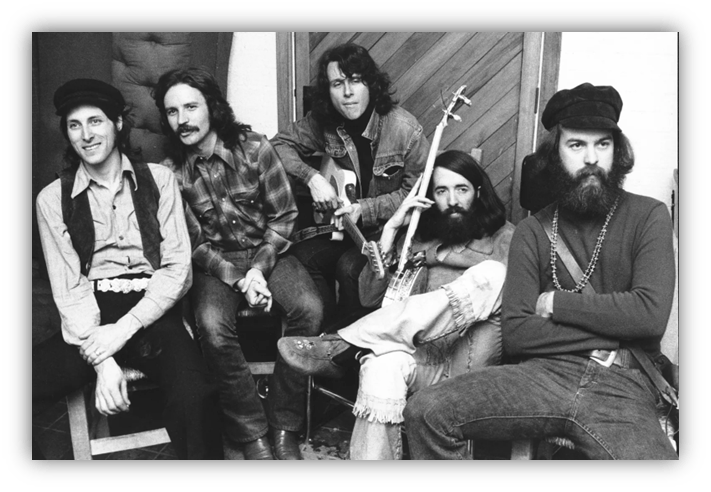

Mandolinist Sam Bush was a chief leader in New Grass and the generation is named after his band, New Grass Revival.

Some traditionalists saw New Grass as disrespectful, but Bush and the other practitioners worked within the genre to expand it. They wanted to innovate with those same traditional instruments: mandolin, banjo, acoustic guitar, bass, and fiddle.

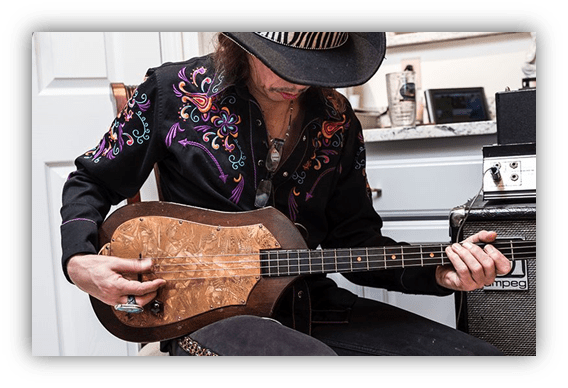

Add to that the dobro, which looks like a guitar but is played horizontally with a slide. This is optional and purists used to grumble about it but it’s now accepted as a legitimate Bluegrass instrument.

The same is true for drums. A single snare drum may or may not be acceptable but a full drum set usually isn’t. Neither are spoons or shakers or washboards. They’re not part of the Bluegrass tradition. The percussion comes from the strings, and mostly from the mandolin’s chop.

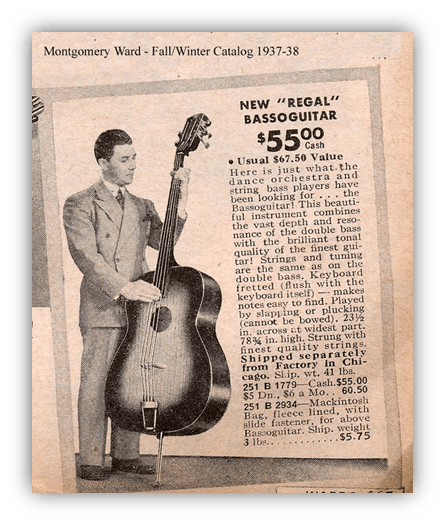

However, it was during this time that electric bass guitar became an acceptable replacement for upright bass.

Part of this is practical. Through the first and second generations, the standard stage set up was for all the players to stand around a single microphone. When a voice or instrument took the lead, that musician would move closer to the microphone.

That was state of the art in the 1940s, but the upright bass was often hard to hear.

Switching to the electric gave the bass its own amplifier.

It just made sense, and while you’ll still see Bluegrass groups use a single microphone, it’s now more likely that each singer will have his own and each instrument will be sent through the PA separately.

That’s how things were done in the Rock and Jazz worlds, and it’s not the only thing Bluegrass picked up from other genres. The third generation is seen as a time of innovation, experimenting with the traditional sound and incorporating influences from Rock, Jazz, and Folk.

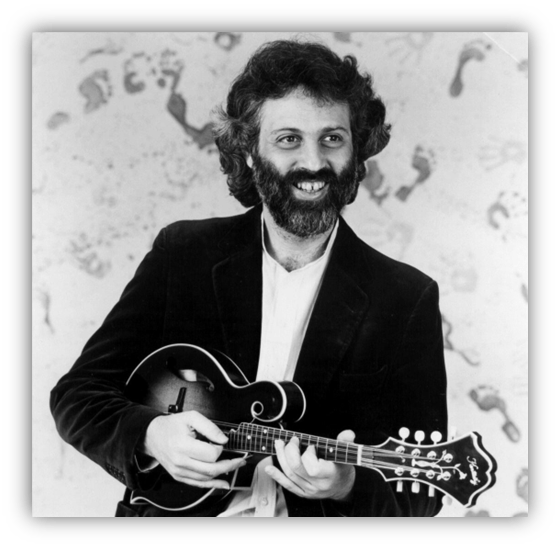

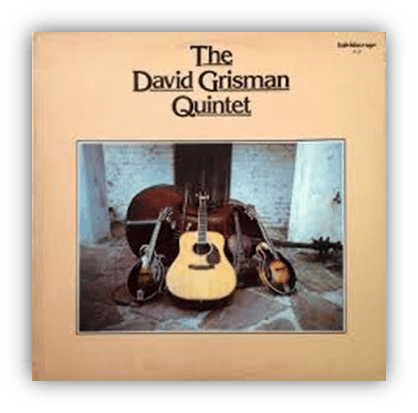

Multi-instrumentalist David Grisman combined all four genres into what he called “Dawg Music.” It’s also called New Acoustic Music.

In the early 60s, Grisman played in the Even Dozen Jug Band with future Pop stars John Sebastian and Maria Muldaur. He was then in the Psychedelic band Earth Opera and a Bluegrass band called The Kentuckians, before moving to San Francisco and meeting the Grateful Dead.

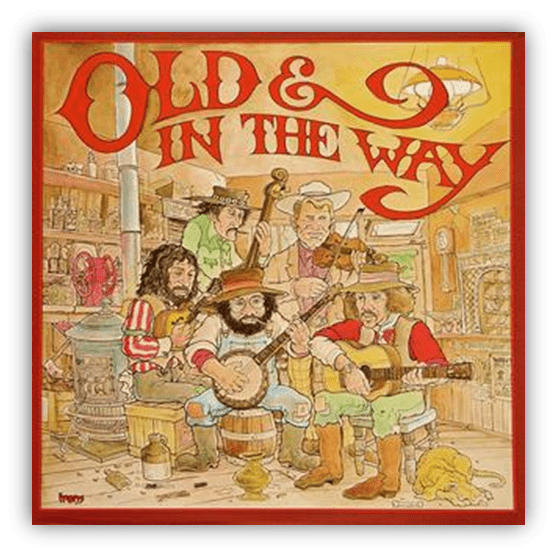

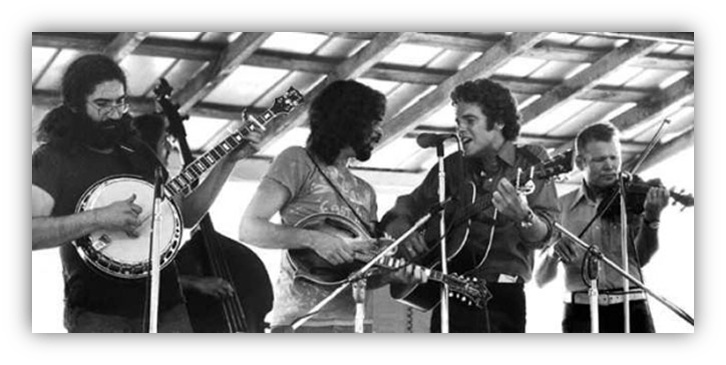

He played on their American Beauty album and formed the Bluegrass outfit Old & In The Way with Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia, Bluegrass legendary fiddler Vassar Clements, and Peter Rowan from The Kentuckians.

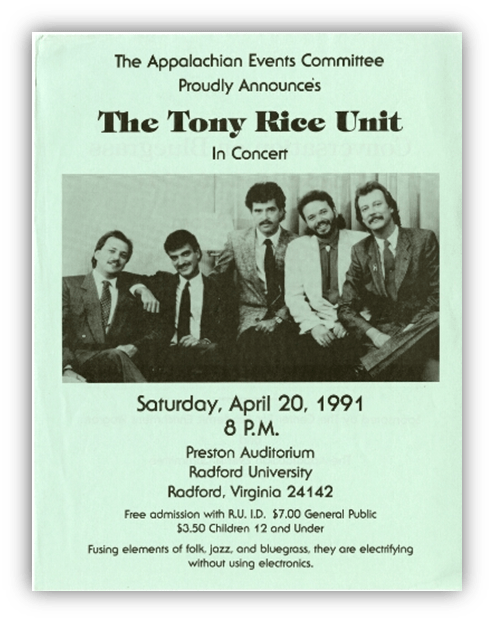

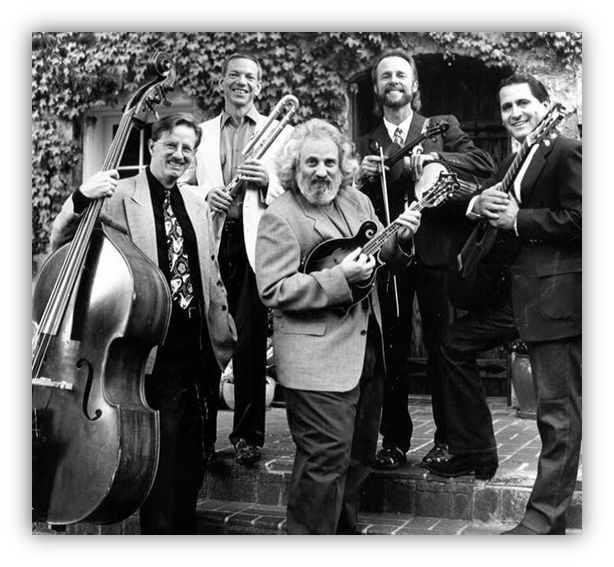

Grisman then put together a quintet which combined the Bluegrass, Rock, Jazz, and Folk he had been playing with Classical and Gypsy elements. The David Grisman Quintet included guitarist Tony Rice fresh off his stint with J.D. Crowe and the New South.

Rice had also played with The Kentucky Colonels and Bluegrass Alliance, and would go on to collaborate with Norman Blake, Ricky Scaggs, Béla Fleck, and Chris Hillman.

He’d also started his own Tony Rice Unit and coined the term “Spacegrass” for his style of instrumentals with fast-paced picking, intricate melodies, and improvised sections.

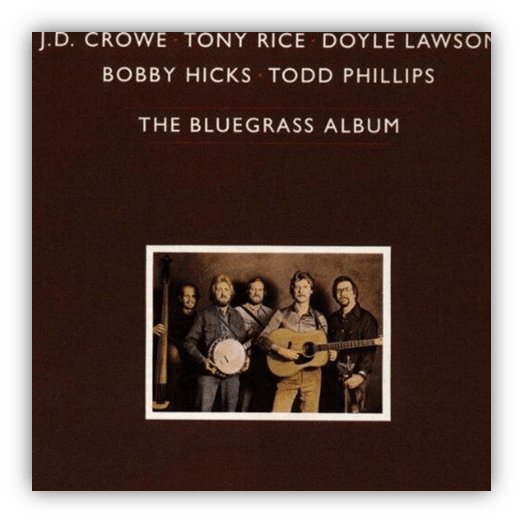

In 1981, Rice wanted to record a new album. He pulled in Crowe on banjo, Doyle Lawson on mandolin, Bobby Hicks on fiddle, and Todd Philips on bass. Everyone except Philips sang.

While it was supposed to be a solo record, Rice was so pleased with the results that he gave everyone equal credit on the cover.

It was called The Bluegrass Album and, since the band didn’t have a name, everyone called them The Bluegrass Album Band. The record was a big hit in the Bluegrass world and marks the start of the Neo-Traditionalist subgenre.

It plays Traditional Bluegrass songs with advanced chops. Though Rice was reluctant to play guitar solos on Traditional tunes which hadn’t featured them, the guitar was thereafter accepted as a lead instrument.

If you get the impression that Bluegrass players move from one band to another willy-nilly, you’re right.

Not only do they seem to like each other, they challenge themselves by trying new situations and learning something from each other, especially in new settings. This is where inspiration and innovation come from.

And this third generation saw the start of Progressive Bluegrass, which appealed to a younger and more diverse audience.

But before things got too avant garde, along came the fourth generation in the 1990s.

We call this generation Contemporary Bluegrass, and it’s still going on. This generation continues to build on the innovations of the 70s and 80s while maintaining a strong connection to Traditional Bluegrass.

Contemporary Bluegrass has a vibrant community of musicians, festivals, and record labels dedicated to both preserving and evolving the genre.

Artists like Alison Krauss & Union Station, The Del McCoury Band, and The Infamous Stringdusters blend elements of Traditional and Progressive

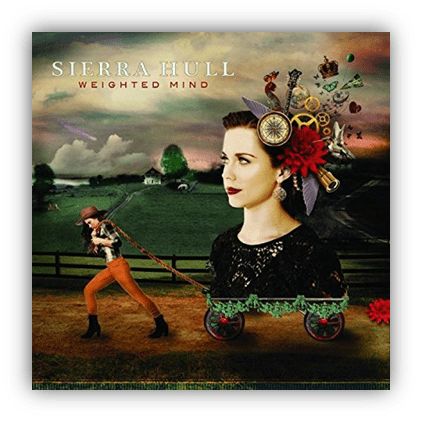

Younger players, like Nickel Creek, Sierra Hull, and Billy Strings, keep that balance going.

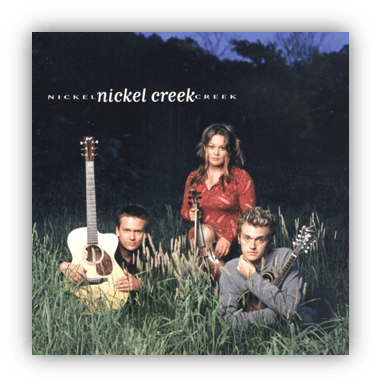

The trio Nickel Creek started as children. When they played their first gig at a pizza parlor, two members were 8 and the old man of the band was 12.

Their parents were all fans of second generation Bluegrass, so that era featured big in their sound. But they have added Progressive elements, and some Pop touches, too.

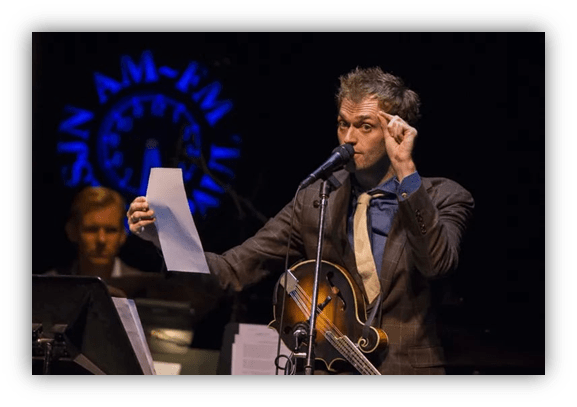

Mandolinist Chris Thile is a remarkable musician, and has since recorded with Classical cellist Yo-Yo Ma, formed the Progressive band The Punch Brothers.

He’s also the current host of A Prairie Home Companion radio show.

Two of Nickel Creek’s albums were produced by singer and fiddle player Alison Krauss, who had been a child star herself. She recorded her first album at age 14 and has, to date, won 27 Grammys.

Some were with her band Union Station, some with former Led Zeppelin singer Robert Plant, some as a solo artist, and some as producer.

Krauss took another Bluegrass prodigy under her wing:

Sierra Hull started playing mandolin when she was 8. At 11, she self-released her first album and that got the attention of Rounder Records, who signed her.

Secrets, her first album for them, was produced by Krauss and Union Station multi-instrumentalist Ron Block.

Before that album came out in 2008, I was lucky enough to be in a band that opened for Sierra at a couple of shows. She was still a teenager, but I felt I was in the presence of greatness – yet she was as friendly and down to earth as you can possibly imagine.

I’ve followed her career and she seems to be exactly the person you see on stage. Unaffected, charming, grounded – and devastatingly talented.

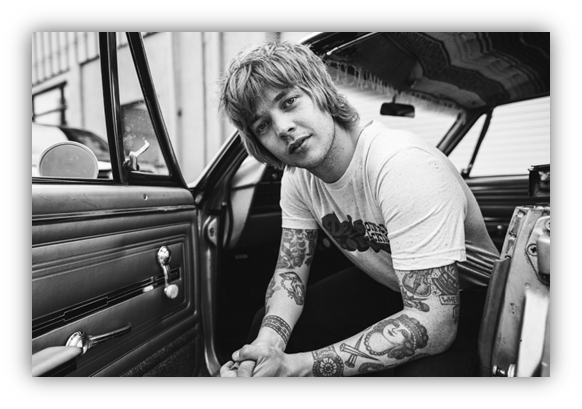

In 2024, Contemporary musicians are pushing Traditional Bluegrass into uncharted territories.

Sierra’s biggest album, Weighted Mind, is stripped down to mandolin, bass, and vocals.

There are touches of Grunge in Billy Strings’ material, and he’s been known to cover Alice In Chains. Molly Tuttle pulls in Americana, Folk, and some Classic Rock.

Alternative Bluegrass acts like Trampled By Turtles and Old Crow Medicine Show combine Punk aesthetics with Bluegrass structures.

It’s worth noting that Bluegrass was almost 100% male until the fourth generation. Women are now a huge part of the Bluegrass scene, and we’re seeing similar changes in Pop and other genres.

So:

- The first generation created Bluegrass

- The second revived it

- The third expanded it

And the fourth ties it all together.

Contemporary Bluegrass works within the Traditional Bluegrass framework, but pushes its limits with virtuosic techniques from Progressive Bluegrass, New Acoustic Music, and other genres, and throws in the occasional Pop cover like during the Folk Revival.

After the 1960s, Bluegrass never really went away, and today it’s as healthy as ever.

Let’s see what happens when the fifth generation rolls around.

Suggesting Listening – Full YouTube Playlist

Flat Fork

The Kentucky Colonels

1964

Ole Slew Foot

Jim & Jesse

1965

I’ve Just Seen A Face

The Dillards

1968

Turn Your Radio On

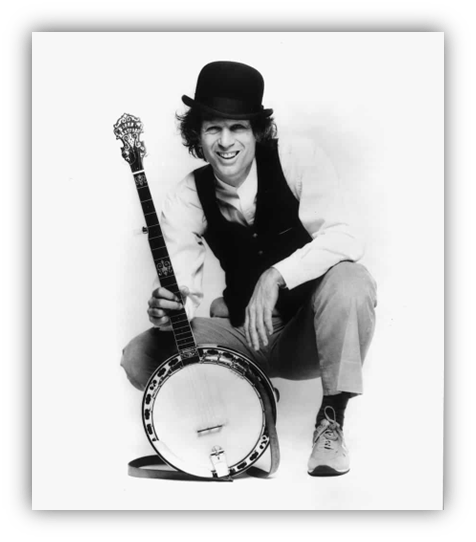

John Hartford

1971

Will The Circle Be Unbroken

The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band with:

“Mother” Maybelle Carter, Earl Scruggs, Doc Watson, Merle Travis, Jimmy Martin, Pete “Oswald” Kirby, Vassar Clements, and Roy Acuff

1972

Panama Red

Old & In The Way

1975

I’m Walkin’

J.D. Crowe and the New South

1975

Janice

The David Grisman Quartet

1979

Blue Ridge Cabin Home|

The Bluegrass Album Band

1981

Whitewater

Béla Fleck

1988

Duke and Cookie

Strength In Numbers

1988

I’m Down

New Grass Revival

1989

Steel Rails

Alison Krauss

1991

In The House Of Tom Bombadil

Nickel Creek

2000

What Do You Say?

Sierra Hull

2011

Fire Line

Billy Strings

2021

White Rabbit

Molly Tuttle

2023.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Great history lesson. I like how bluegrass has had several cycles of expansion and evolution, yet it’s retained its connection to its roots far better than contemporary Country Western, which is little more than radio pop with a twang or two.

In keeping with the spirit of my recent posts, here is a slice of Red Scare bluegrass. Not Grandpa Jones’ best moment, but it’s still a solid song:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7TbFkt_YIP0

Wow, hadn’t heard that before. Some things never change.

Loving this playlist.

No mention of the whole “O’Brother” thing? Maybe that’s better described as Old Timey music (though so is some of this playlist, IMO). Great stuff.

Way back during S1 of Bill’s wonderful series, he’d fretted that the Suggested Listing section was perhaps too long or superfluous. I assured him that it was neither/nor.

As your humble layout editor, I can tell you that Bill takes the curation very, very seriously.

Nice of @Low4 to concur and recognize the effort.

I do take it seriously and @Low4 raises a good point. The “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” soundtrack renewed interest in Old Time and Bluegrass, and did wonders for Ralph Stanley and Dan Tyminski, so it was probably worth a mention.

On the other hand, my word count was already past my limit and I didn’t want to push it into a Part 3. Though if I had done so, the story of the White brothers in The Kentucky Colonels would’ve been nice to cover, too.

I’ve been demoted! Figures.

Tyminski has a great story about telling his wife that he would be singing on the soundtrack of a new Hollywood movie, and told her who he would be voicing. Apparently her response was that her dreams were coming true; her husband’s voice and George Clooney’s face.

Not demoted at all! Sometimes the coin is heads, sometimes not.

Around 2010, I went to see Sierra Hull at the Station Inn on what was probably a Tuesday. Tyminski was on guitar. At some point she said, “Dan, why don’t you sing one?” and they launched into “Man Of Constant Sorrow.” The place went nuts. On a Tuesday.

My other brush with greatness that would’ve been in Part 3 was when I got invited to a block party. They said we should bring our instruments, so I brought an acoustic bass. I ended up sitting on folding chairs in a driveway with Roland White on mandolin and Markey Blue on guitar and vocals. I knew Markey already (I think she invited me to the party) and was impressed with Roland. I didn’t know anything about Bluegrass but he was a great player and a really nice guy. He was originally from extreme northern Maine so we had a few things in common to talk about and it was only later I found out who he was. Yeah, no wonder he played so well.

Lord, what a great column, Bill! I feel like a kid in a candy store with all these familiar (and a few unfamiliar) artists and tunes.

The first Bluegrass song that hit me hard and made me a fan was Jim and Jesse’s cover of John Prine’s classic “Paradise.” My grandfather was a miner in Muhlenberg County, and Central City was like a second home — where my grandmother lived until she passed away in 2004. Where I spent a week every summer, going to Bible school at my grandmother’s church and walking down to the public pool every afternoon. Where I had a parallel best friend waiting for me (one of the neighbor kids).

So the lyrics of that song hit very close to home, “Daddy won’t you take me back to Muhlenberg County / Down by the Green River where Paradise lay / Well, I’m sorry my son, you’re too late in askin’ / Mr. Peabody’s coal train has hauled it away”

https://youtu.be/V9zZD3TEPa0?si=LJE46ycOzcSv20KE

Wow. What a song. I just looked at Paradise on Google Maps satellite view and, yeah, looks like many, many acres have been hauled away. I can see how it hit you hard.

Where I work at the Ohio River Forecast Center, we forecast the Green River, on which is a forecast point at Paradise. This song gets brought up occasionally when we have flooding there.

Great stuff. The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band is up there as one of the best band names ever. From the playlist The Dillards take the win on best Beatles cover, there’s a real sense of longing in their interpretation of I’ve Just Seen A Face.

While the Nickel Street track has a strong overlap with folk. Specifically there’s times where I felt I wouldn’t have been surprised if you told me they were an Irish folk act.

The NGDB is indeed one of the best band names ever. And also a very good description of the soul of the band. They are eccentric, multi-faceted, and totally dedicated to their music of many different styles.

The funny thing about these bluegrass festivals…

I went to a few during my big bluegrass heyday, from ’96 to ’98. Some were outdoor affairs with a largely young audience and a very hippie vibe — even if many of the musicians were traditional old timers.

But some were for and about the old folks. My friends and I went to one in Jekyll Island, Georgia (apparently still an annual event: https://evansmediasource.com/events/jekyll-island-new-years-bluegrass-festival/). In a large indoor setting, we were the only people in attendance under age 60. Sincere musical prayers and no dancing in sight, but some brain-melting virtuosic music all the same. And the old timers were proud to see us young’uns there enjoying the music.

When the hippies embraced bluegrass, many traditional musicians were perplexed at first. Jim & Jesse were once asked at one of these young, San Francisco engagements, where they played their music with psychedelic lighting all around, something to the effect of, We enjoy playing for this new generation, but our core audience is still people who make biscuits every morning.

Late to the party, as I was tied up all day yesterday. But, wow, what a party. I love this music, and, as always, VDog does a tremendous job of putting it into words.

Can’t wait to get into the playlist.

I’m late to the party, but great articles, Bill. You mention the covers…I think that bluegrass is one of the most likely genres to cover other songs. I hear bluegrass covers of a vast number of different types of songs. Just yesterday I heard a cover of Eric Clapton’s minor early 80s hit “I Can’t Stand It”. It’s really amazing how good some of those bluegrass interpretations are.