Alexandria, VA, 2017:

I am sitting at my computer at home, and I click a link that my friend had sent me.

It’s the teaser trailer for a new movie she’s excited about: the upcoming remake of Stephen King’s IT.

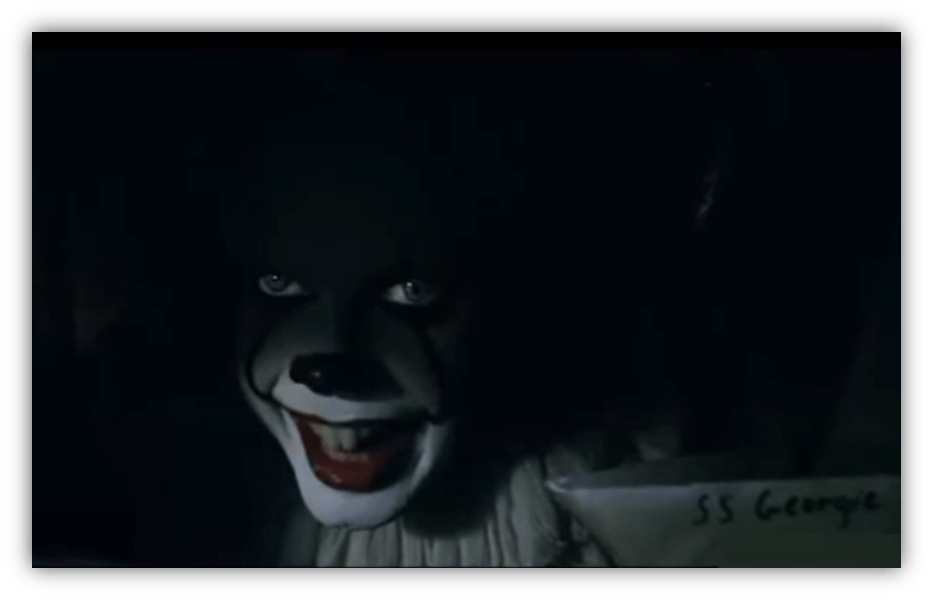

The teaser opens with the now-iconic scene of young Georgie Denbrough running alone through the rain with his paper boat in hand.

The eager little boy trips and falls, and then his boat sails ahead without him, hurriedly riding the rainwater stream until it disappears into the darkness of a storm drain. I know what’s coming…

This particular image has been burned into my memory since childhood. When I was nine years old, I had watched the television miniseries when it aired on ABC. I now know quite well what creature will emerge from the storm drain, because my brain won’t ever let me forget.

It…It’s a clown.

Or, “the clown.” Pennywise the Dancing Clown.

Somewhere in the recesses of my mind, I can see his face peering at me. Not Tim Curry as Pennywise in 1990, or the new actor, Bill Skarsgard. I see Pennywise as he truly is.

As “IT.” For just a split second, I feel the presence. And I shudder.

1.

For the most part, when I happen to think about Pennywise the Clown, I do see Tim Curry.

Painted in red and white makeup, acting goofy one moment and vicious the next. He was sheer perfection in that role, and allowed King’s creation to enter our pop culture pantheon of motion-picture monsters and maniacs.

Despite its limited budget and censor regulations of the ABC miniseries, this first visual rendering of IT made quite an impression on viewing audiences everywhere, due in no small part to Tim Curry’s magnetic performance as Pennywise.

Unfortunately, no amount of acting can make cheap special effects look any scarier.

This version of IT is not an immortal horror classic that it’s sometimes touted to be. Don’t get me wrong, it was unbelievably scary when I was a kid. But for the most part, it’s actually pretty funny to watch now.

Strangely enough, that disconnect is quite appropriate for the IT story. We adults certainly have a hard lot in life, but childhood really is no easier. It’s just that we forget how intense it all was! As children we needed to brave uncertain terrains and endure the wilderness of our unfiltered imaginations. And then we forget it all, and assume it was a great time. This is a major thematic undercurrent of IT. If only the miniseries could have captured the terror that I had felt watching it as a child…

Philadelphia, PA. 1986:

I wake with a startle from what sounds like something scratching at the window. I lift my head up and peer into the darkness of the bedroom. The scratching continues.

Suddenly, I notice strange malevolent shapes in the room, moving slowly, as if they are waiting with anticipation before they pounce.

“It’s just the trees again” I tell myself. Tree branches blowing in the wind, scraping against the bedroom window. I had checked a few nights before.

All I’m seeing are the shadows cast from the lights outside, streaming into the room. That’s it. There’s nothing to be scared of.

…Right?

Still, even now, I don’t dismiss the IT miniseries out of hand.

A lot thought and effort went into adapting King’s story for the small screen. And despite its limitations, the effort really shows!

In just over three hours, the production team was able to capture the most important beats of Stephen King’s sprawling, rambling 1986 novel, even preserving its fractured temporal structure.

Seven friends from the fictional Maine town of Derry once banded together to confront the shape-shifting thing that fed on their fears and murdered children around town.

And now they must come back together and finish what they had tried and failed to do as children: to kill IT, or be killed.

The story cuts back and forth between the main characters as children in 1960, and as adults in 1990.

The principal reason for the constant cuts back and forth in time is because the adults don’t remember anything about their past together: most of the memories were repressed, unknowingly. Until now.

This narrative device evokes a real psychological coping mechanism for traumatic memories, which is crucial for the story’s larger narrative about confronting one’s fears. Key moments come back to the seven friends of “the Loser’s Club” via unexpected triggers, and the mystery behind the story is slowly revealed to them and to the audience as they are able to confront more and more of their past.

Say what you will about the silly special effects, I remain impressed with this production’s attention to character writing and themes.

2.

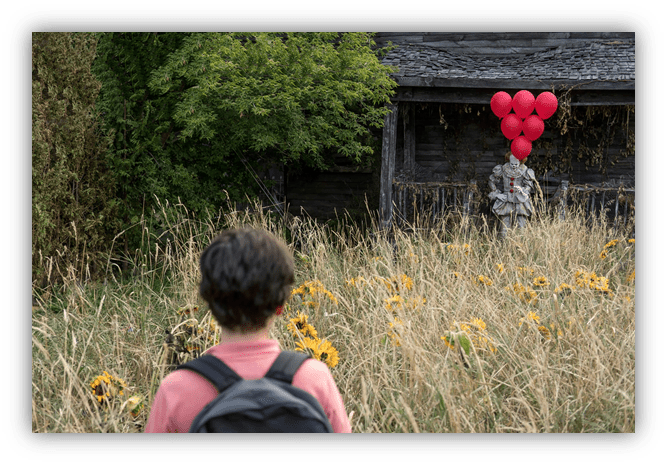

Still, given the modest production and dated effects of the miniseries, it was practically fated that IT would eventually get a big-budget film adaptation.

And in 2017, Andy Muschietti indeed brought Pennywise to the big screen.

Between its two chapters, the remake totals more than five hours, so the story does include some elements of the novel not found in the 1990 miniseries. But, there are also some major deviations from both book and show, most of which I feel are to the detriment of this new version.

Puzzlingly, the new production team decided to tell their story with a perfectly linear timeline:

Chapter One features the children, and Chapter Two features the adults.

This means there’s a repeating story beats over the two films (the heroes get scared by the evil thing, confront the evil thing, defeat the evil thing).

Even worse, this narrative un-jumbling saps the story’s power with respect to its themes of confronting fear, and healing the scars of the past. As a result, the new IT just feels more like spooky fiction than something evocative of real horror.

Additionally, the settings of the story are each pushed forward in time, with Chapter One taking place in 1986 and Chapter Two in 2016. This move could have been a stroke of genius had it been executed more thoughtfully. Most of the forms that IT takes in the book and the miniseries come from old 1950s horror movies: werewolf, mummy, etc.—all appropriate for the children in that time period.

Alas, despite the children’s rooms being decorated with 80s horror films, we don’t get any terrifying “real life” manifestations of Pinhead, Chucky, or the Gremlins to stalk the kids of this updated setting.

The references merely exist to amuse their audience with nostalgia and cleverness, not as a vital part of the story. And so the time update feels not just pointless, but like a wasted opportunity.

Despite all that, is the new film scary?

Well, about as scary as the1990 miniseries was, actually!

Maybe a touch scarier in certain scenes, but not by much. There’s a definite creepiness to how Tom Skarsgard plays Pennywise, but he’s so obviously predatory, there’s no ambiguity or dissonance of tone to lend tension to a scene.

Ambiguity is arguably what makes clowns a bit creepy in real life, and King milks that to unnerving and surreal effect with Pennywise. In this new version, the clown has just two modes: leering like a predator and lunging like a goofy monster. As ever, the CGI makes everything cartoonish. The jump scares are cheap. At least the miniseries had the excuse of a small budget…

3.

Still, I can’t be too harsh. Anyone trying to adapt IT into a story for home or theatre viewing has their work cut out for them!

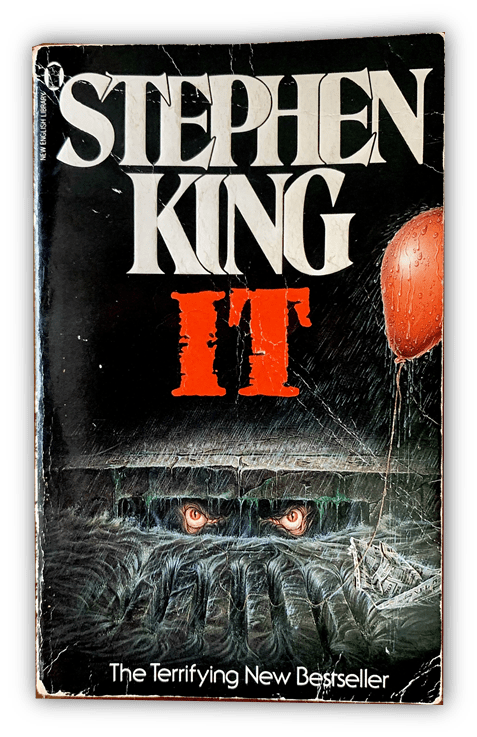

If you’ve never read the book, you may be surprised to learn that IT is not simply the story of a spectral clown who feeds on children’s inner fears.

King’s work is a sprawling, near-psychedelic rumination on the very nature of human evil, one that combines historical, political, mythological, and psychosexual dimensions into a transcendently monstrous narrative for readers to tackle, wrestle with, defeat, and hopefully grow from.

In truth, the novel is long, rambling, and indulgent, and quite often hard to read for its brutally uncensored material.

And it’s weird as hell.

In the novel as well as the new movie, we learn that IT began as some “thing” that landed in what would later be Derry, many millions of years in the past. Was it an alien? God? Demon? What’s the difference?

All we know is that it is an incredibly powerful, largely incomprehensible being. We also know that it is self-interested, and eventually it learns that fear makes its prey so much more delicious to eat, especially the fear of human children. There is power in belief, and especially in human frailties.

Knowingly or unknowingly, the residents of Derry are offering blood sacrifices, or at least turning a blind eye, to this dark presence that inhabits their lands.

Sometimes that presence can even act through the humans of Derry, using their anxieties to enable cruelty and violence toward vulnerable targets. Including their own children.

And yet despite the regular recurrence of ghastly violence in the town, despite the blood of children being spilled, perhaps because of it, Derry continues to thrive. And here we get to the political dimension of the story.

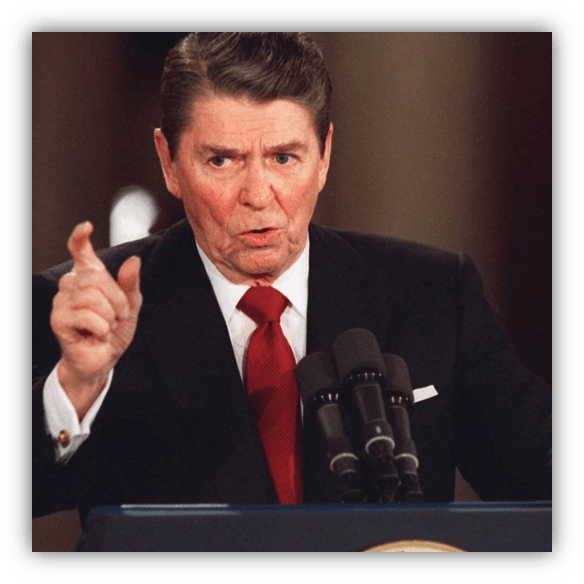

“We have every right to dream heroic dreams. Those who say that we’re in a time when there are not heroes, they just don’t know where to look. You can see heroes every day going in and out of factory gates. Others, a handful in number, produce enough food to feed all of us and then the world beyond…Their patriotism is quiet, but deep. Their values sustain our national life.”

– Ronald Reagan, 1981

When people think about how IT begins, they typically think of the scene of young Georgie Denbrough running in the rain with his sailboat, only to stumble upon Pennywise in the storm drain.

But people tend not to think about the very next chapter, which takes place in the 1980s.

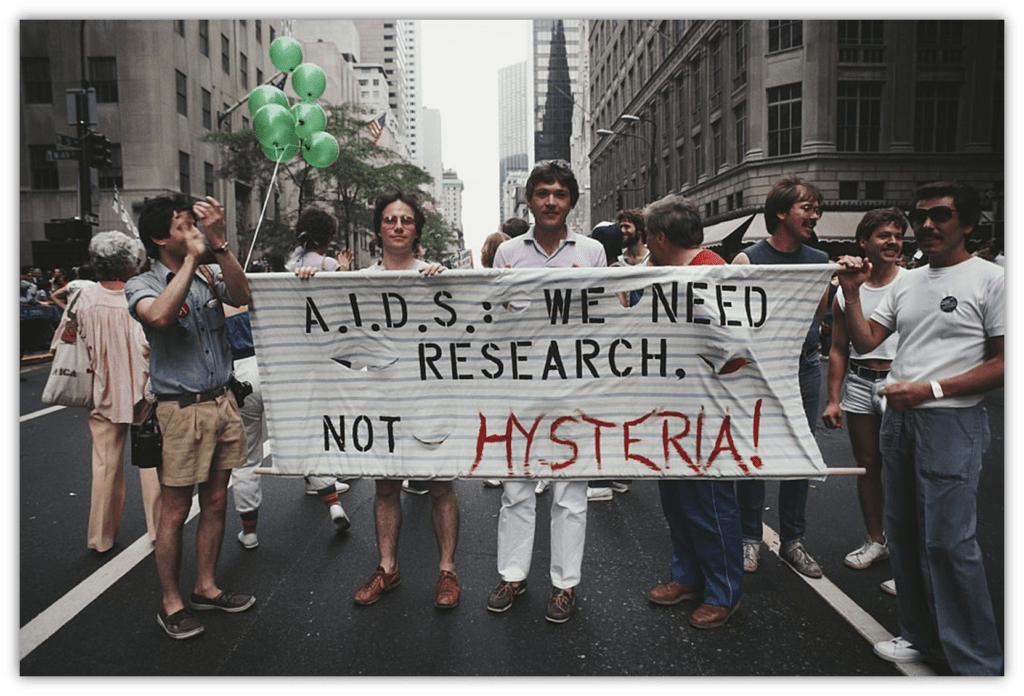

This is where a gay man is brutally attacked and eventually murdered near a town fair, simply for dressing “queer” and kissing his boyfriend in public. Why was this included in the novel?

IT was written over the course of the early 80s, in the midst of the Reagan Revolution. Appropriately, the present day period of the story takes place in 1984, where economic conditions are booming. All of the Loser’s Club friends who left Derry eventually grew up and found some sort of financial success. And Derry itself is thriving as a small but growing city.

Given that gay men had been dying to a new virus with no help coming from their government, and prominent conservatives were declaring AIDS to be punishment for the gay lifestyle, the cruelty and negligence captured in this early chapter serve as an important dimension to remember about Reagan’s 80s, the dark underbelly of his “shining city on a hill.”

The victim’s boyfriend knows the source of the evil that killed his lover, and he tells it to readers in the second chapter of the novel: the heart of evil is Derry itself. The town and its people. The very setting that seems to be flourishing. You know, aside from those gruesome attacks no one wants to talk about.

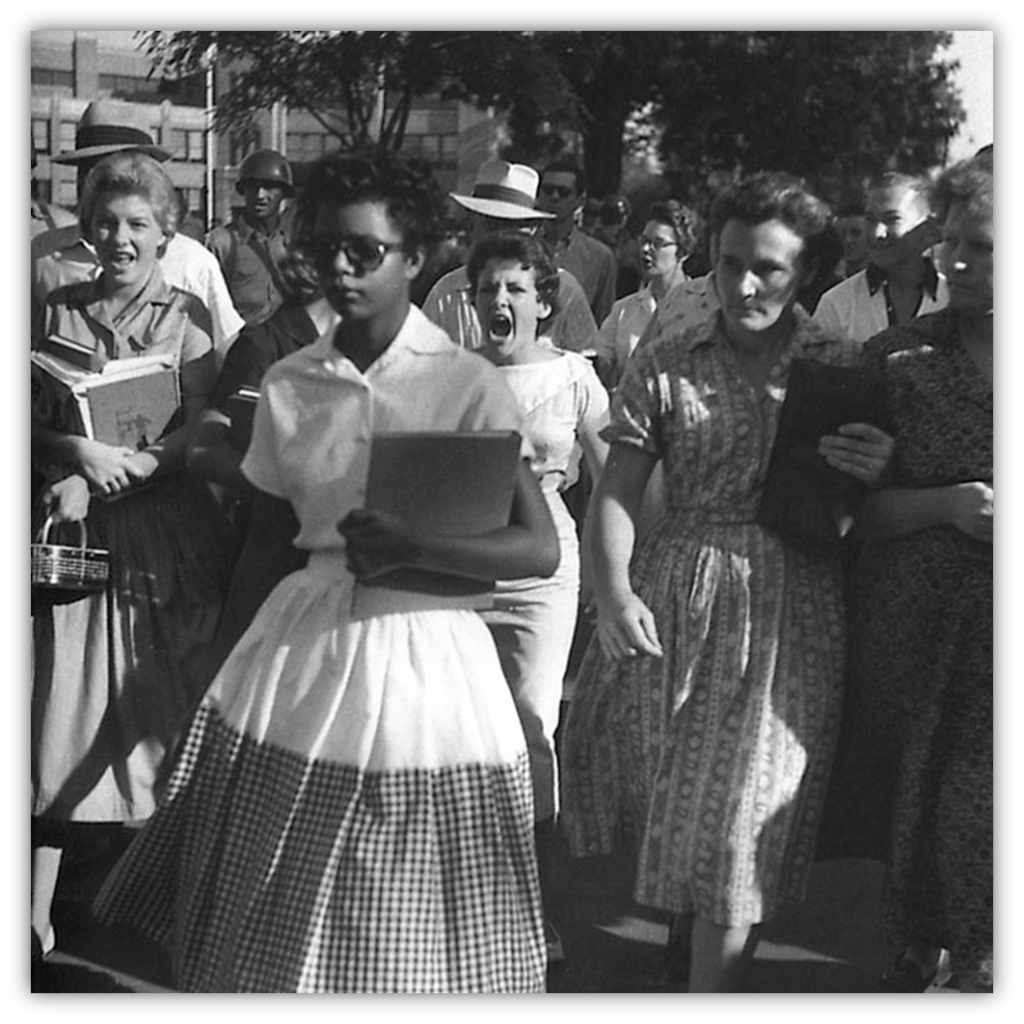

The other principal time period in the story is 1956-57. Most people would look back to those earlier times as simpler times. Times you wish you could go back to. The good old days.

And so King goes to great lengths to detail the manifold ugliness of human spirit that existed in those good old days.

Rampant racism. Misogyny. Fat-shaming and child abuse disguised as stern parenting. Authorities who could protect the weak and marginalized, but just don’t want to.

Human ugliness is everywhere in this book, and it is rather hard to digest.

And that’s the point.

Reagan’s American Dream had a dark side. It had a hidden cost. Whether through active malevolence or a willfully blind eye, countless cruelties were endured for the sake of order, tradition, and economic progress.

As tough as IT can be to get through, I do find it incredibly rewarding.

Because it’s not just an exhaustive screed of human evil, it’s a story about confronting evil.

About reckoning with demons of the past, about cutting through the sources of division, about coming together, about mastering one’s fear and anxieties. About healing.

IT is Stephen King’s masterpiece, and one of the great horror stories of our time.

It may be a lumbering mess, but that’s what makes it so powerful, so resonant for our own lives.

It’s also what ensures that its true essence will never be captured on the screen.

Alexandria, VA. 2023:

I’m scrolling through Netflix for possible movies to watch, and I see that the IT remake is available. I consider putting it on to rewatch it, but…

Nah.

I’ll just put on the Tim Curry one. 🙂

My favorite part of the movie version was the King cameo where he admitted to being bad at writing endings. Because the ending to the book was crap. Even with that being the case, there was so much depth and such wonderful characterization in the book that was missing in either filmed adaptation. As there always must be in such adaptations.

I’m not going to lie. I went to the film hoping to be frightened. And…I just wasn’t. No fault of anyone, I was just too familiar with the plot, I think. The actors did a good job. But there was nothing classic about the movie.

Tim Curry’s Pennywise was classic. His performance brought out the attraction and the repulsion. Of course, Tim Curry himself is a classic, but that could be an article all its own.

I thought that the ending scene with Audra on the bicycle was sweet, corny though it was.

The Ritual of Chud scene was weird and hokey, but I kind of like it. King embracing his inner “Weird Tales” geek with aplomb. There’s no good way to render that on the screen though.

If by the ending you mean how the children got out of the tunnels, yes…I figured I would just skip right by that part in my write-up…

How the children got out of the tunnel is what I meant. And, yes, good idea to skip it. I wish King had.

There have been so many good (Misery, The Shining, Carrie) and bad (Maximum Overdrive, Sleepwalkers, Cat’s Eye) Stephen King adaptations, it’s almost a genre unto itself. In my mind, both IT’s are squarely in the middle, with the Tim Curry version ahead of the Bill Skarsgard one.

The novel came out when I was in middle school — a classmate in my speech class carried it with her for like a month (it’s a THICK book), and I was kind of impressed and intimidated. Not only because she was a 13-year old reading a 1,000-page book, but how scary I imagined it to be (and she confirmed).

I went to Bangor, ME, a couple of times for work several years back. I dropped by the Stephen King house (I understand he doesn’t reside there anymore, but it’s now a writer’s retreat). It’s really a sight to behold — the old Victorian mansion with spiderweb and bat wrought iron fence. The pictures in the linked article give a good flavor of the place:

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/stephen-kings-house

Depending on my frame of mind, Piper Laurie’s performance as Margaret White can either be terrifying, or terrifyingly funny. Laurie makes “camp” scary. I can’t really point to another example. Out of those three films you categorized as good, Carrie is my favorite.

Doctor Sleep isn’t bad.

Doctor Sleep corrected some of the mistakes that the movie version of The Shining made. And Ewan McGregor is a wonderful actor.

The original Carrie is such a gem! And yes Piper Laurie really made the movie. I grew up in a Biblical enough place that her performance rang true… and that’s what made it scary! And I grew up with cruel enough teenagers that the bullying Carrie experienced rang true. Oh and by the way, it’s my life story, lightly fictionalized. 😜

I am wondering why you did not include in your list of “so many good” adaptations, the masterpiece that is The Langoliers… 🤔

I should have included The Mangler as well… an honest-to-God horror movie about a murderous dry cleaning machine. And it’s not a parody…

The best King adaptation isn’t a horror story, it’s The Shawshank Redemption

Nicely done. Through my early teens I read everything Stephen King had written up to around 1992. Saw plenty of the film adaptations as well. At which point I completely left him behind and have never picked up another book by him.

I think in part it was developing my tastes and finding new areas to explore and in part regarding him as something from my childhood. Something to be left behind as a sign of immaturity and wanting to feel as though I was more discerning than the masses reading his books. The arrogance of youth in other words. Now that I’m not so young there’s just too many books and not enough time so haven’t got round to revisiting him.

I saw the original tv series but have little memory of it other than the iconic scene you mention with young Georgie and the iconic vision of Tim Curry as Pennywise.

I heard something recently that IT is responsible for the now seemingly common Coulrophobia. They asserted that IT didn’t just popularise the fear of clowns, the persona of Pennywise created it entirely. It didn’t exist until IT. I can’t believe this is true, surely there were creepy clowns before Stephen King’s imagination spawned this demonic vision.

He dressed up like a clown for them

With his face paint red and white

And on his best behavior

In a dark room on a bed he kissed them all

-Sufjan Stevens

“…surely there were creepy clowns before Stephen King’s imagination…”

Yes!

Yes, certainly John Wayne Gacy played some part in that pop culture fear as well.

Check out the movie “”Killer Klowns From Outer Space”!

He’s not a clown, but I think that Conrad Veidt as Cesare from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari may have played a role in the public’s fear of dramatically painted faces. Veidt also supplied the terrifying visage of The Man Who Laughs, which directly inspired the creation of a rather popular killer clown from comic books: The Joker.

Let’s not forget this abomination:

https://youtu.be/QIuXv7Y8QA4

Terrifying…

I was pretty much the same way. I gorged myself on Stephen King in Grades 8-9, then discarded him in favor or writers I felt were better. Some of that judgment was justified, and some of that was the arrogance of youth as you say.

I revisited IT a few years ago, and it’s really held up well. As I mentioned in the post, it’s not without some major flaws and frustrations, but it’s brilliant for all that.

The Harold Bloom/Stephen King feud was entertaining.

King used to use the backpage of Entertainment Weekly to argue for well-written genre fiction. In his opinion, without saying so explicitly, he defended his own work as being on par with “another boring Paul Auster novel.”

Apparently, the late Bloom had undergone a meltdown when Stephen King was awarded the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters in 2003.

Anybody who reads fiction on a regular basis, more often than not, I suspect, began with King.

Hopefully, all those J.K. Rowling fans never stopped reading. I remember novelist A.L. Kennedy balked at the idea of the Harry Potter series as being required reading for the school curriculum overseas. It’s jealousy, more than anything.

I was a much stronger advocate for Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy at the time, and found Harry Potter to be overrated. While I still find Northern Lights/The Golden Compass to be so much better than the early Potter installations, I must admit that Rowling’s series really is better overall, particularly how the story ends. HDM feels rather quaint these days, while the final book of Potter feels more relevant than ever.

My first forays into “adult” fiction were the book club editions of The Shining and The Stand on the seemingly giant bookshelf in our living room (and a paperback copy of ‘Salem’s Lot that I checked out of the town library after watching the miniseries in 1979). Of course, I only skimmed to the “good parts” at first… it wasn’t until my teen years that I went back and read them cover to cover.

This is a very clever response. I’ll let everybody else enjoy the comment without pointing out the analogy that everybody else can figure out for themselves.

Purely unintentional, but rereading what I wrote I can totally see it now. 🙂

IT was always going to tough to adapt.

One of the main themes is fear being driven by the unknown. When the monster under the bed becomes a real, solid thing it can be dealt with. The same child that imagines a werewolf also imagines the silver bullet that dispatches it. That works in the book, but on film it’s anti-climactic.

There’s also the matter of IT preying on children. That’s explained in the book as being because adult fears are more amorphous and less visceral. An adult fears losing their job and becoming homeless or having some debilitating injury, things that aren’t easily replicated by IT. On film that means adults in the audience won’t be scared.

Plus that whole sewer sex scene was gross 40 years ago and is still gross now. But removing it, as both adaptations did, leaves a large thematic hole in the story. In the book we’re privy to the thoughts and drives of the characters, which gives the scene necessary context. There’s no way to make that work on screen with child actors.

Yes, agreed. In the books, you can say, “it was a werewolf, but it was nothing like you see in the movies,” and readers can try to imagine what that’s like, but such an image is by definition impossible to faithfully render in a cinematic medium!

That sewer scene is evidence of King’s addiction, in my opinion. Nobody in their right mind could think that was okay.

It’s also evidence that Stephen King had final say over his books after The Stand. Any editor in their right mind would have excised that section. Or maybe everybody had the same addiction and didn’t notice.

King can’t use the Brave New World defense. Huxley is extrapolating the future. I thought that novel was unfilmable, but according to the internet, there were two small-screen adaptations.

“It’s just the trees again” I tell myself.

Clearly you had yet to watch the original Evil Dead at this point in your life. 😁

As others here, I’m so well versed in the book versions of King’s works that I usually spend my viewing time picking apart the film adaptations (why did they leave that part out? what the hell is going on, this wasn’t in the book!), usually ending up disappointed.

As Phylum did, I liked the Tim Curry version for the most part, you could be fooled into believing he was a real human until he decided to reveal his frightening side. Whereas Skarsgard’s Pennywise had no normalcy about him whatsoever to contrast with the creepiness…if I were a kid, I’d take one look at his bizarre shaped skull and get the hell out of there.

… did someone say Evil Dead? 💀

Why do you think the filmmaker changed Pennywise the Clown’s gender?

Also,

it was a little Gilligan’s Island, but Pennywise’s original form was ingrained in my headspace. I don’t want to sound like an It fanboy, but I was a little disappointed. What do you think? Was the clown’s original form too outdated for the 21st century?

Can’t say for sure. If runtime and budget weren’t such limitations for the miniseries, it’s possible that they would have included the scene of the adults destroying IT’s nest of eggs. As for the 2017 adaptation, the writing logic there is beyond me. Who thought it was a good idea to make “everything floats down here” a line about floating in the air???

By original form do you mean the incomprehensible Lovecraftian elder god who humans inadequately visualize as a sort of gigantic spider? I dunno, despite the opium and racist dread that informed Lovecraft’s work, I’d say that his brand of cosmic horror is perfect for our times.

Oh, wait a minute. Pennywise isn’t a spider? The adults only think it’s a spider? So Pennywise is a shapeshifter without an original form?

It does have a true form, just one that puny human brains can’t properly comprehend.

Like, when I hear “I Zimbra,” my brain hears “African lyrics,” even though I know the lyrics are from a dada poem by Hugo Ball. My brain doesn’t know what to do with those lyrics, so it just goes to the most convenient percept.

From a historical point of view, I was introduced to Mr. King in the mid-seventies with the movie “Carrie” with Sissy Spacek. I bought the book and it was totally different then the film.

I bought “Salem’s Lot” before the TV series and was hooked on King forever.

His description of a New England fall is so dead spot on, I’ve never forgotten it.

I’ve just about have every novel, short story, compilations and serials (“The Green Mile” is actually nine different stories).

I’ve read of his descent into drug addictions and his love of being in a rock band and I think of him as being a long lost cousin who never left the East Coast (despite a foray into Colorado, a dose he gave us in “The Shining” and “The Dead Zone”).

Outside of the movies of the Thirties and Forties that brought us Sherlock Holmes, The Falcon and The Saint, I can’t think (at this time) of a an author who has so intrigued Hollywood (hit or miss) as King has.

My children watched the original “It” and they were scared beyond belief

but they watch it now and are more concerned with the children who had

to deal with Mr. Pennywise than the actual fright scenes.

What I wouldn’t give to see Curry’s Pennywise at some point break into ‘I Do the Rock.’

Not a big King fan. Mostly because I quake at horror in a general way. I do like some of his short stories, though. However, Phy, your explication of the three versions was enlightening, even for this non-indulger.