These days, monotheism is everywhere.

Most people in the world profess a belief “in God,” rather than a belief in gods, or in spirits.

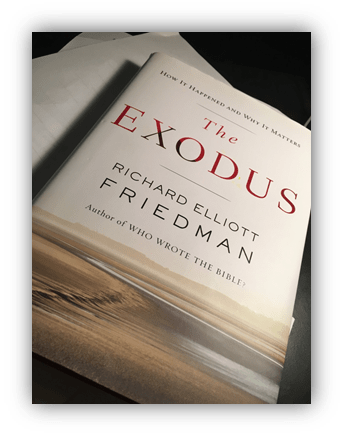

But as Richard Elliott Friedman points out in his book Exodus, polytheistic religions dominated human cultures for most of our history, by far.

So what exactly does monotheism offer to the people who practice it?

We just covered the evolution of Jewish culture from polytheism to staunch monotheism, but was there a purpose, or a function, behind such a shift? Is a polytheistic society different from a monotheistic one?

In his book The God Delusion, Richard Dawkins names a litany of ancient pagan deities, and then smugly observes:

“We are all atheists about most of the gods that humanity has ever believed in. Atheists just go one god further.”

Is he right that it’s just a matter of arithmetic in the number of “delusions” we choose to believe in? Or does belief in One God offer something that belief in many gods does not?

Friedman argues that monotheism was important for the cultivation of community tolerance and respect for aliens, for outsiders, for people who were different. In essence, “love your neighbor as yourself” is at the heart of monotheism, at least Jewish monotheism.

The Torah states “the same law applies both to the native-born and to the foreigner who lives among you.” (Exodus 12:49.) Such a sentiment was certainly relevant for the tribe of Levi, who themselves had a past as resident aliens.

Among the Levite sources of the Torah, the command to treat aliens fairly shows up a total of 52 times!

Among the one non-Levite source? Not once.

Given that Ezra himself was a descendant of Aaron, and thus a Levite, it’s not surprising that the final Torah that he assembled and presented to the people made this theme of acceptance a priority.

Yes, most of us will immediately think of all of the biblical passages and historical events that show violence and intolerance rather than such professed love.

Yet Friedman concedes as much. There will always be strife and tribal dynamics when humans are around. But everything is relative, not just to different points in history but to different cultures of the time.

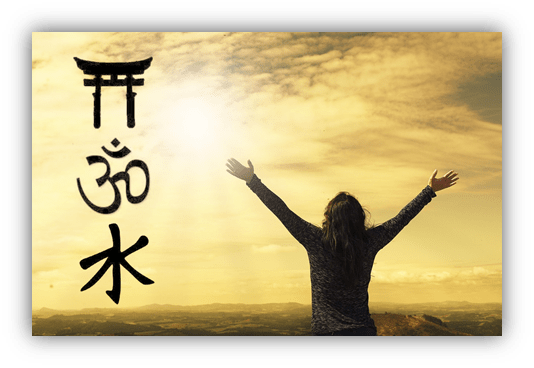

Also, let’s not forget that democracies and republics began in pagan, polytheistic Greece.

And our collective understanding of ethics and morality was enriched by Hindu, Confucian, and Shinto sages, among others.

Friedman also concedes these points. He’s careful to state that the relationship between monotheism and moral tolerance is not absolute.

But in general, the shift from an anthropomorphic god or gods to a cosmic entity had important social consequences.

Early pagan gods had something like a physical form, they had human moods and emotions, and they were limited to one element of power, or to one geographic region. Compare that to a transcendent all-knowing God who created the entire universe.

Such a God enabled humans to transcend petty divisions of locality, color, and even creed, as this was a God that ruled over everyone, every person on the planet.

Common origin,

higher ideals,

… a universal sense of order.

At the very least, such notions stemming from a cosmic, ever-present God offered an increased possibility of making peace among diverse factions.

As long as those factions behave exactly as we say, that is.

[zing! …. okay, okay, yes… there are limits…]

…to be continued…

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Heart” upvote!

Here we go. Sorry to have jumped ahead earlier.

Never apologize for being right!

(Cheers from Lyon)

I took a graduate course on Environmental History, and a funny fact was pointed out to the class:

Before a culture achieves farming, they tend to be polytheistic, with a strong sense of animism. Anthropologists think that’s because of those cultures’ reliance on nature around them to support them.

Once sedentary farming takes hold, it is the sun/sky that enables that culture to survive…and so begins the worship of a sun god/monotheistic religion.

Sorry, just getting to these comments!

Yes, I think there is truth to that framing, at least broadly speaking. The worship of one supreme celestial god also seems to coincide with religious and practical concerns about astrology and astronomy, and it is common among societies that happen to be governed by a supreme human ruler.

Though such god-patterns are strongest in broad strokes. The devil’s in the details! 😉

Ah Dawkins. The God Delusion is the only book of his I’ve read. Some good points I thought but wrapped up in such a smug, self satisfied, prescriptive package that made it a slog to get through. I also learnt that I’m the wrong sort of atheist as I’m happy to accept that I’m not better than those who do follow a religion and we’re all welcome to our own beliefs.

I definitely didn’t get a sense of love your neighbour from him.

I’ve mentioned before that that The God Delusion is my least favorite book of his. It’s rather insipid, despite having some inspired passages here and there.

I do highly recommend The Ancestor’s Tale and The Greatest Show On Earth. The latter one is unfortunately suffused with a deep sense of frustration bordering on paranoia about anti-science bad faith, but that’s understandable given the reality of anti-evolution movements out there. And both books have a sense of wonder and geeky curiosity to them that make them quite pleasurable to read.

Maybe monotheism evolved as some people and societies gained a more solid understanding behind the why’s of things happening the way they did?

It’s possible, and I think that is what Enlightenment philosophers tended to believe, at least until a lot of them started to lean closer to Richard Dawkins toward naturalism, pantheism, and outright atheism.

I like to think that no one attempt to describe or understand the divine gets it right, but none get it completely wrong. Whether it’s because it’s simply an expression of our human nature, or we are in fact accessing something supernatural (or both), there seems to be something that’s beyond rational description: the divine is the ineffable. So whether it’s one God or many gods or a guiding spirit, the answer will be yes. And no. And Other. And mu.

I could look this up on Google, but it’s more fun to ask a guy with a PhD.

I have a question about Shintoism. Many years ago, I read Iris Chang’s magnum opus. Her explanation for the actions of the Japanese Imperial Army was their religious beliefs. Chang wrote that practitioners of Shinto prioritize the individual over community. So Chang is arguing for Christianity. I’m writing from memory, so excuse me if I’m misremembering horribly.

Did you see Makoto Shinkai’s Weathering with You?

A girl wants to save Japan from going underwater. She offers herself up as a sacrifice to stop an unending rainstorm. This is my analysis, and it might be a wrongheaded one if I don’t have the tenets of Shinto down pat. In a western film, you let the woman be the hero; she dies so other people can live. But in Weathering with You, the male decides that her life is more important than the lives of the community. And I remember sitting in the audience, thinking oh, wait, what did I read ten years ago?

He saves the girl, the girl who could fix the fallout from global warming. But that means Japan will eventually be swallowed up by water.

Movies usually have an open or a closed ending.

Weathering with You seems to have both.

Lol, if a PhD grants any authority, mine’s limited to the weeds of visual perception. For any of this stuff, I speak only as an enthusiastic amateur. 😅

I am unfamiliar with Chang, but it’s an interesting observation about Shintoism. What originated as a regional animism eventually became the state religion of an empire, and it mutated accordingly. Imperial Shintoism seems to me more like a hierarchical pantheon of deities governed by small group of high gods, including the solar goddess Amaterasu. The gods are also much more moralistic than the spirits of Shinto folk stories. In my opinion, later Shintoism is closer to something like Catholicism–another refashioning of an older tradition for an empire–than true animism.

I did see Weathering With You, and I’d have to think about it some more. It actually struck me as rather individualistic film, with a much more prominent Western touch to it than Hayao Miyazaki’s films–which are obviously also an influence. I think what makes it like the Western films for me is that the woman believes that her purpose is being served and her fate is sealed, but the man comes along and saves her, even at the cost of the entire city. It’s very Romantic with a capital R. Contrast that with Spirited Away, which culminates in Chihiro mastering responsibilities for the sake of her family. Not to mention fall in love with a river god. Can’t get more Shinto than that!

And yet, re: Western influence, my wife kept commenting in Paris how various historic buildings and neighborhoods reminded her of different Miyazaki movies, or shops in Japan.

You were gone for so long. Forgot to check. Thank you for answering my post.