Okay, so we’re trying to digest this notion that some of the major early tales of the Bible can be traced to just one tribe of Israel, and no other.

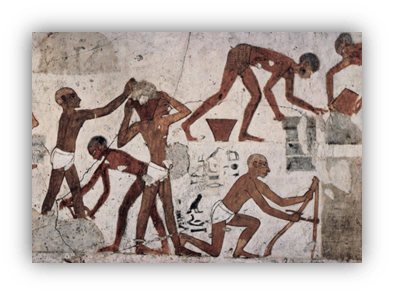

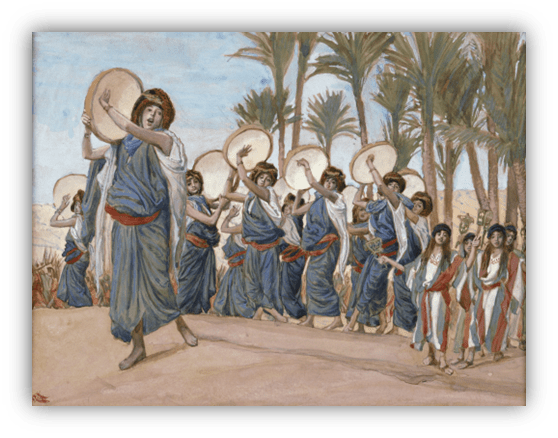

Slavery in Egypt…

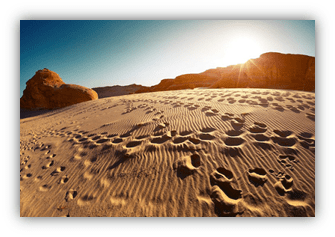

the exodus through the desert…

the “victory” over the pagan Canaanites…

All of these stories reflected the historical experiences of the landless, priestly tribe of Levi, so named for their status as attached outsiders, or resident aliens.

As for the other tribes of Israel, well, it seems that they had been those pagan Canaanites all along.

Instead of being slaughtered, they welcomed the Levites into their lands, then adopted sacred stories of a common origin to merge their identities into one people, one nation, one history. From many, into one. E pluribus unum.

But what about the multiple gods that these people worshipped?

How could that practice be reconciled with the idea that the people of Israel were the chosen ones of Yahweh?

I Am That I Am

Before getting into the other gods, let’s concentrate on Yahweh, who commanded that His people “shall have no other gods before me.”

Was He always worshipped by the Israelites? Or did worship of Yahweh come from Egypt, via the Levites?

Maybe a bit of both, as we’ll see.

Scholars like Richard Elliott Friedman argue that the Levites were indeed largely responsible for the transformation of Israelite religion to monotheism over the centuries.

Moreover, the religion the Levites practiced in Egypt may have already been monotheistic, or at least monolatrous (i.e., worship of one god, even if others exist).

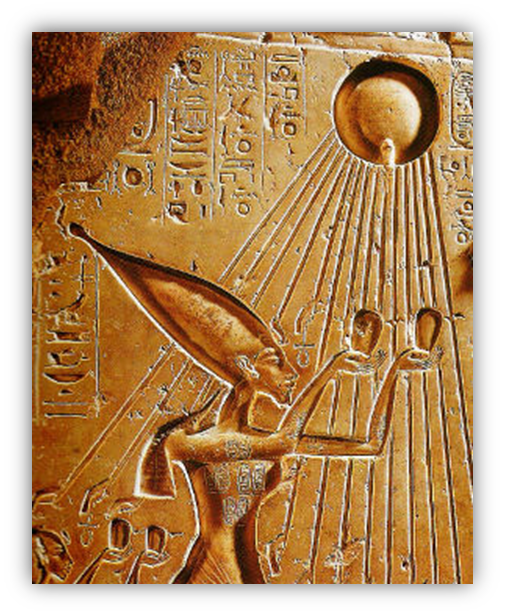

One possibility that’s entertained is that the Levites once lived peacefully in Egypt under the Pharaoh Ankenaten, who himself worshipped a single God, Aten.

After Ankenaten’s death, his successors destroyed his sarcophagus, attempted to destroy all records of his reign, and abolished his monotheistic practices. It may be that Aten was adopted and renamed by the people later called Levites.

Or perhaps they simply had similar practices, and always worshipped a God named Yahweh.

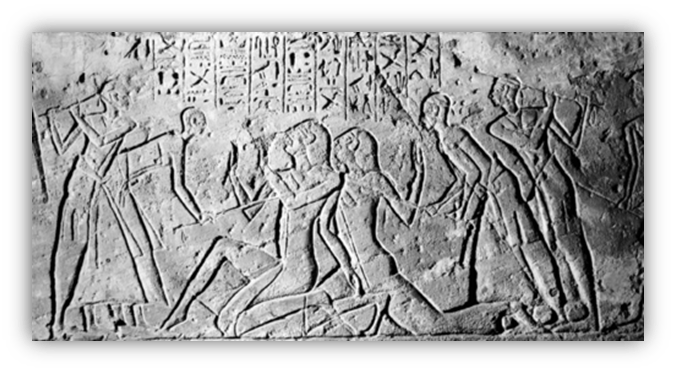

For instance, there were groups of Semitic Levantine people called the “Shasu” by the ancient Egyptians, and were said to be enemies of Egypt.

One of these groups were “Shasu of Yhw,” which some scholars have connected to Yahweh. We may never know the full details for sure.

In any event, even a resemblance to Ankenaten’s god might have been enough for the later Pharaohs to label the worshippers of Yahweh as enemies, slaves, pariahs, you name it. And so the people of Yahweh fled.

We know that they eventually assimilated into Canaanite culture, serving as their priests. How could these people, these devotees of one true God, make peace with pagan polytheists?

Wrestling With God

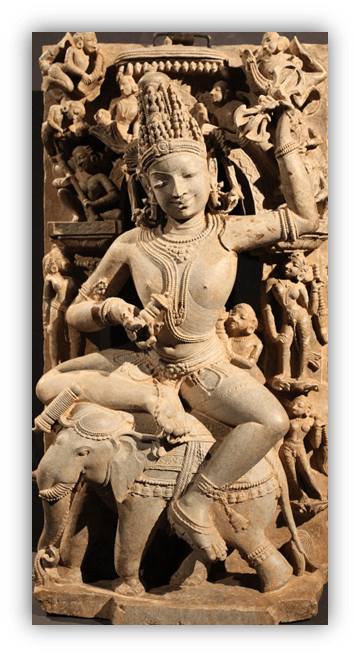

Archeological evidence from the Southern Levant region shows a steady and uninterrupted practice of worship of certain gods and goddesses. Who were these figures that the ancient Israelites worshipped?

- There was El, the king of the gods.

“El” simply means “the god.”

- El’s wife was Asherah:

The mother goddess (whose name was also generically used to mean “the goddess”).

- There was Ba’al: god of fertility and agriculture.

- Yam: god of the sea.

- Shapash: goddess of the sun.

- Mot: god of death. And so on.

In the Bible, Ba’al and Asherah are usually described as evil idols worshipped by some foolish Israelites tempted by their pagan neighbors. In fact, they were prominent deities in the early pantheon of the region. It was only later that these revered entities were reframed as rival gods of Yahweh, false gods, and even demons.

However, there’s an interesting exception: while Ba’al gets plenty of hate in the Bible, the pagan god El does not. El was regarded by Canaanites as the king of the other gods, the head honcho of the pagan pantheon. Why wouldn’t he be Yahweh’s biggest threat?

He certainly could have been Yahweh’s biggest threat, but instead of seeing a rival, the Levites saw in El a strong resemblance to Yahweh.

These Canaanite people worshipped the correct god after all: the king of all other gods!

This congruence gave way to a syncretism of sorts, a way to forge a new unity in the face of clashing narratives and priorities. A way to establish peace and common identity among disparate peoples.

Of course, this syncretic joining of different community’s gods into one entity was only relevant in one instance.

Namely, for the Almighty, the king of gods. Those other gods? Well, they had to go.

Find out how next time…

… to be continued…

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” upvote!

I forgot to give a shoutout to Dagon, the father of Ba’al who somehow later got conceived as a fish god, and subsequently showed up in literary works such as Paradise Lost, Middlemarch, and The Shadow of Innsmouth by HP Lovecraft.

Most of my knowledge from this period of Canaanite history comes from Graham Hancock’s “Sign and the Seal” which I’ve written about before.

He discusses the development of a monotheistic religion as well, and suggests a strong connection between the Qemant of Ethiopia and the early Abrahamic religion, which may/may not have been monotheistic.

Looking forward to the rest of this series!

Hmmm…interesting. I’ll have to check it out!

Sounds like the origins of Santeria (or the many other ways Christianity infiltrated cultures by combining with them).

Yes, syncretism is a topic I find endlessly fascinating (if my earlier series about Tarot cards hadn’t already given that away…)

The Baal in Volker Schlondorff’s Baal doesn’t seem to have any religious subtext. Or maybe it does and I missed it. Did Brecht drop the apostrophe in Baal intentionally, or is this a Baal independent of Ba’al? I ask because Baal in the Schlondorff film is an antihero. I need to buy an ethernet cable so I can watch it again. Change your cable provider, and all of a sudden, your BluRay player doesn’t work.

I only know the songs that David Bowie included on his Baal EP, so I don’t really have a good understanding of the plot. Based on those songs, I’d say that, at best, the tie to the Ba’al myth is something like the connection of Joyce’s Ulysses to the Odyssey. Or maybe it was just a name he liked!

It is interesting to note how many times the Torah mentions the importance of treating the resident aliens in the land of Israel as equal members of the community and the insistence that they had all the same rights and privileges as the native people. This would certainly support the theory that the Levites, the priestly tribe who wrote the Torah, had roots as resident aliens. It seems to have been a custom that was not widely practiced in the region.

One very minor quibble. We “know” very little about the ancient people who became Israel. We have strong suspicions and a myriad of fascinating theories, some more likely than others. But our actual knowledge, as in provable fact, is very limited.

Hey, no reading future chapters in advance!

(Including the bit about knowledge. I go for punchiness sometimes, but it’s important to make clear)

Mr Dutch loved Stargate (show moreso than the movie). My tangent watching with him over the years has been what has provided me with most of my knowledge of Egyptian gods, lol. Pretty sure Baal was their ultimate villain as well.

I wonder what it was that led the one pharaoh to decide there was only one God for worship? I mean, that’s a pretty radical shift for a society that has established detailed mythologies on a vast assortment of gods.

It was Ra. 😀

My guess is that it was similar to Constantine’s motivation to accept the Christian God: one people governed by the one true ruler, blessed by the one true God.

Given that framing, I’d actually be interested to know why it didn’t stick. How the reform is implemented likely matters a lot.