Bill Bois’ Music Theory For Non-Musicians™

Season 5: Episode 1:What Makes Funk, Funk?

We’ve got the beats:

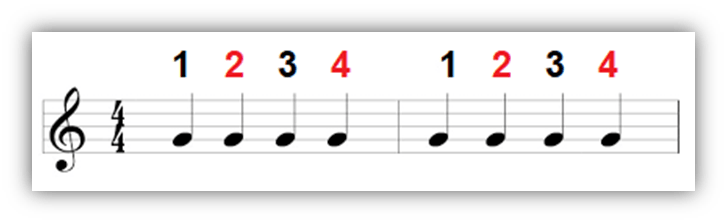

- I mentioned the backbeat in the What Makes Rock & Roll, Rock & Roll? article. A backbeat is when the emphasis is on the second and fourth beats of each measure.

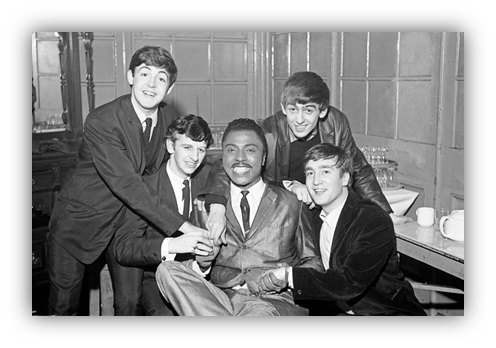

You know it from Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, and The Beatles:

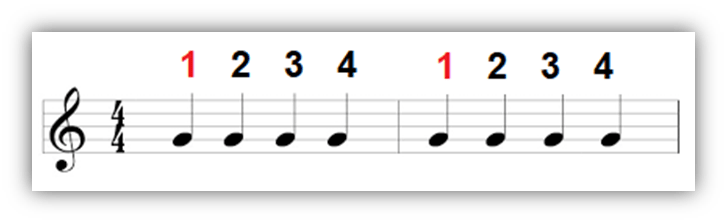

- The What Makes Ska, Ska? article went over putting the accent on the offbeats, meaning on the “ands” between the beats.

You’ll hear this in rocksteady & reggae, too:

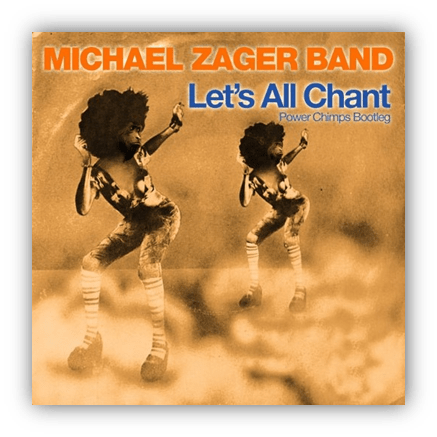

- And in the What Makes Disco, Disco? article, I talked about the “four on the floor” beat, with a heavy bass drum on each of the four notes.

We know it from every disco song, ever:

Now, what happens if you put the main emphasis on only the first beat?

You get funk.

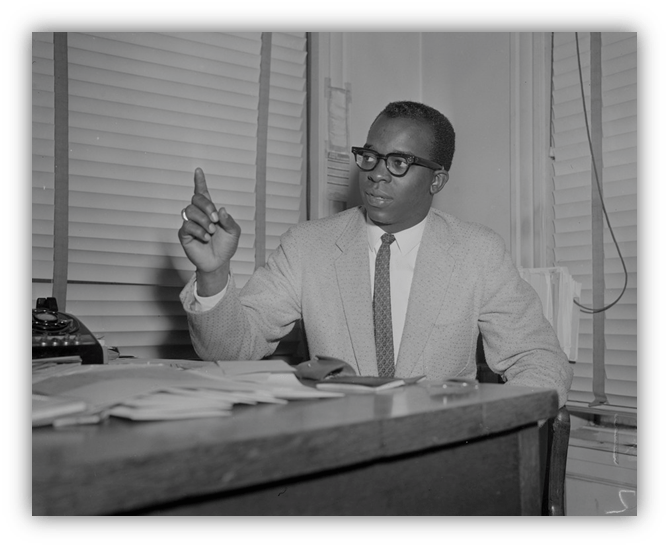

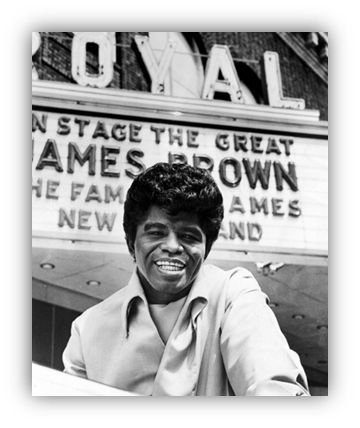

One man is responsible for this rhythmic change.

You know him as the “Godfather of Soul” and “The Hardest Working Man In Show Business.”

But he’s also the Creator of Funk.

James Brown was already a star.

He had joined the Famous Flames in 1953 as the drummer, but soon became the lead singer.

Bobby Byrd, who led the group, recognized that Brown was going places and figured giving Brown center stage was better than letting him leave to start his own group.

Byrd didn’t want the competition.

Despite the success of their singles “Please Please Please” and “Try Me,” all the original members left the group, except for Byrd. Brown put a new band together and rehearsed them to perfection. And if they played a bad note or danced out of sync or showed up late, he docked their pay.

So, they got very good.

He knew what he wanted. He taught the band to play his new songs by standing in front of each member singing their part until the player learned it. He began treating every instrument like a drum. Funk is all about the rhythm, whether it’s a scratchy guitar part, or a percolating horn section, or the drums themselves.

Brown said the first funk song was 1964’s “Out Of Sight.”

That’s when he started thinking about using every instrument as a rhythm instrument.

It’s not the funk of his later songs “Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag” or “Cold Sweat.”

But it where the rhythm’s emphasis started to shift to the “1.”

Sure, stuff happens on the other beats, but the “1” is always accented. This comes straight from African music.

Now, Africa is a big place, and we shouldn’t lump all its music together.

But you’ll find the “1” stressed in juju music from Nigeria, soukous from the Democratic Republic of Congo, highlife from Ghana, and many other styles.

Whether Brown explicitly knew this or not doesn’t really matter, but he got the idea somewhere.

It’s part of funk’s “unapologetic blackness,” as historian Kevin Powell called it. Funk is intertwined with race and the lingering effects of history on black people. The civil rights movement of the 60s certainly plays a role.

The only black people on the charts at the time played inoffensive, genteel music. Berry Gordy, head of Motown Records, saw to it that all their releases could be sold to the largest audience possible.

That naturally included white people, so Motown songs were about love and other universal emotions, and their performers were elegant, sophisticated, and dignified.

All their urban or rural edges were polished off.

James Brown’s funk, however, was directed towards a mostly black audience. He used hip slang, and that infectious funk groove. Some of his songs, and many funk songs to come, stay on the same chord through the entire song, because funk is about the beat. Chord changes are optional.

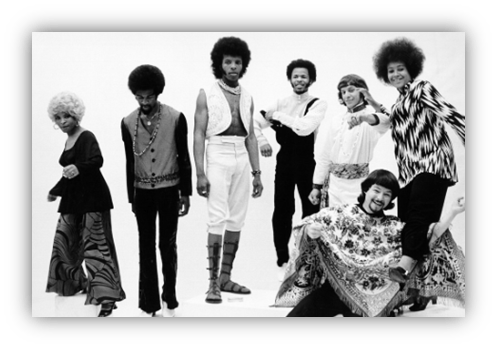

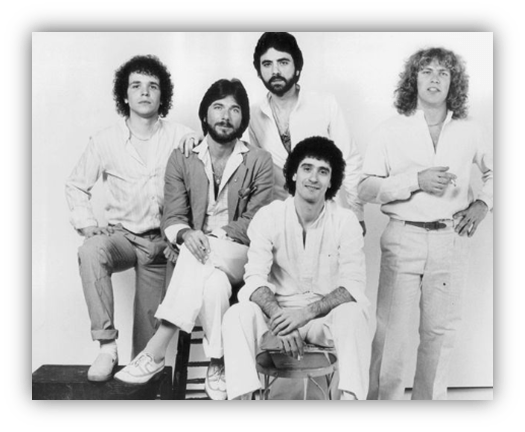

That’s not to take anything away from 1970s white funk acts like Wild Cherry and The Average White Band. In the 60s, however, Sly Stone put together a band of blacks and whites and men and women called The Family Stone.

America wasn’t used to seeing integrated groups on TV. It was disconcerting for a lot of people then, though we’d think nothing of it today.

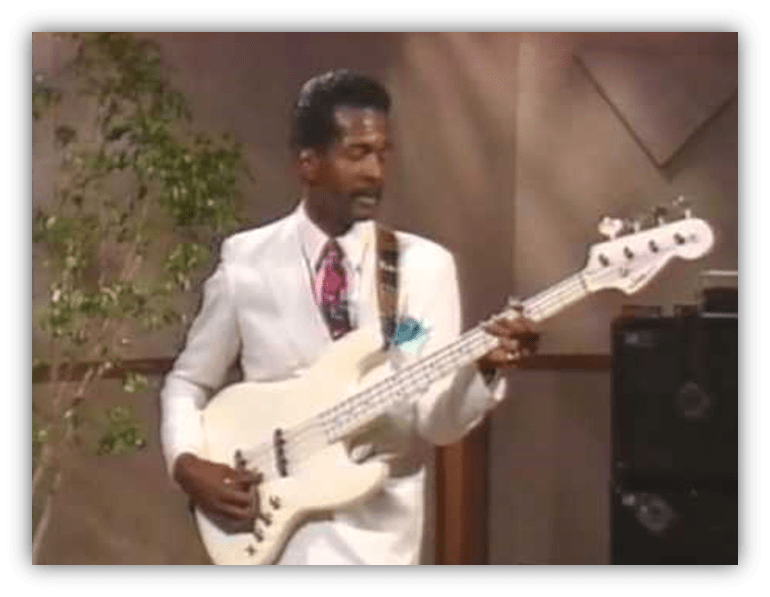

Sly & The Family Stone’s songs could be smooth like Motown, but mixed in a little psychedelia and had that funky rhythm. A big part of their sound was Larry Graham’s bass guitar playing. He invented a technique that we now call slapping and popping. As a child, he had played in his mother’s band. When she fired the drummer, apparently to save money, young Graham had to play in a way that implied drums.

He did this by slapping the strings with the side of his thumb to imitate the bass drum. This usually happens on the 1.

Then he imitated the snare drum by pulling a higher string away from the bass’s body and letting go.

That created the popping sound.

A little slapping and popping goes a long way. But when used judiciously, it’s doggone funky. It’s a prominent part of Sly And The Family Stone’s “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin).”

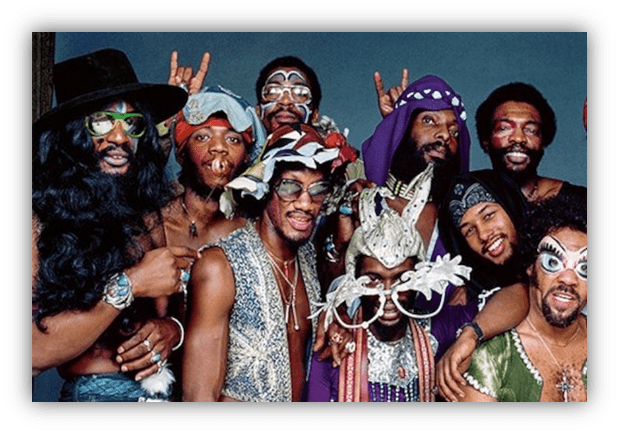

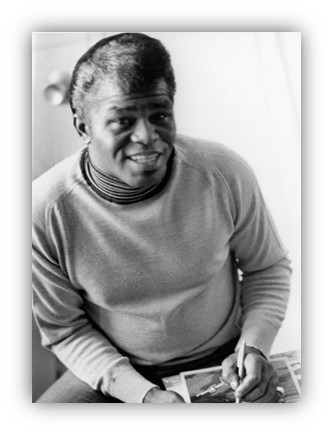

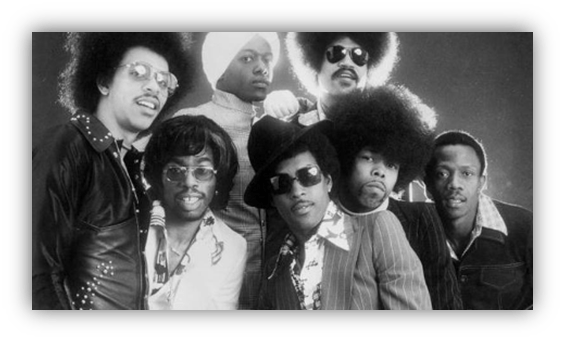

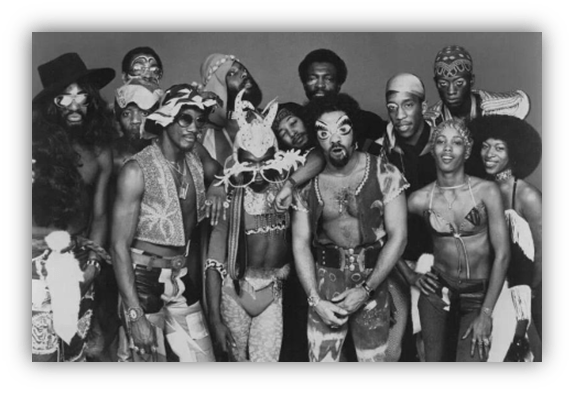

Like James Brown, George Clinton started in a different genre.

He created a doo wop band in the 1950s called The Parliaments. Due to contractual problems, he lost the rights to The Parliaments’ name, so he brought the backing band to the front of the stage and they performed as Funkadelic.

When he regained the rights to “The Parliaments,” the same group of musicians now had two names and were signed to different labels.

It became more of a collective than a band, and there were multiple spin-offs with different members taking the lead role. Some albums were released under one musician’s name, like a solo record, but they were by all the same players.

Later, they would tour as Parliament/Funkadelic. Everyone called them P-Funk.

Where James Brown would fine his musicians for playing a note out of place, George Clinton gave P-Funk players all the freedom in the world.

Not only could they write and/or improvise their own parts, they could wear whatever they wanted. Their outfits got wild. There were no rules.

Except to make it funky.

Clinton and team developed a mythology around the band’s origin. They thought it important to show black people in nontraditional roles, such as being astronauts. As Clinton put it, “And nobody had seen ’em on no spaceships!” So P-Funk concerts of the 70s included a spaceship that flew over the audience and landed on the stage. From its door, Dr. Funkenstein would emerge.

It’s more than I can go into here. But the point was to show that black people can be, and do anything.

Funk was black music for black people.

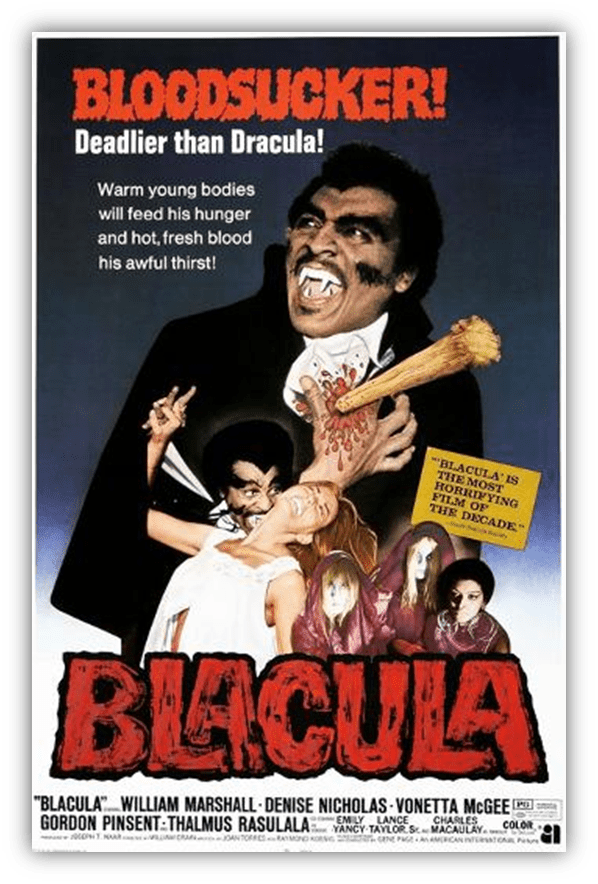

Simultaneously, Hollywood was releasing films directed at a black audience. A genre called “blaxploitation” included movies like Shaft, Superfly, and Cleopatra Jones.

There was even a subgenre of blaxploitation horror movies.

The accompanying soundtrack albums included a lot of funk music.

Following the Civil War, many free blacks moved north for factory jobs. A lot of those jobs are gone now, so we call that area the Rust Belt, primarily Indiana, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. Though James Brown was from South Carolina, Sly Stone from California, and George Clinton from New Jersey:

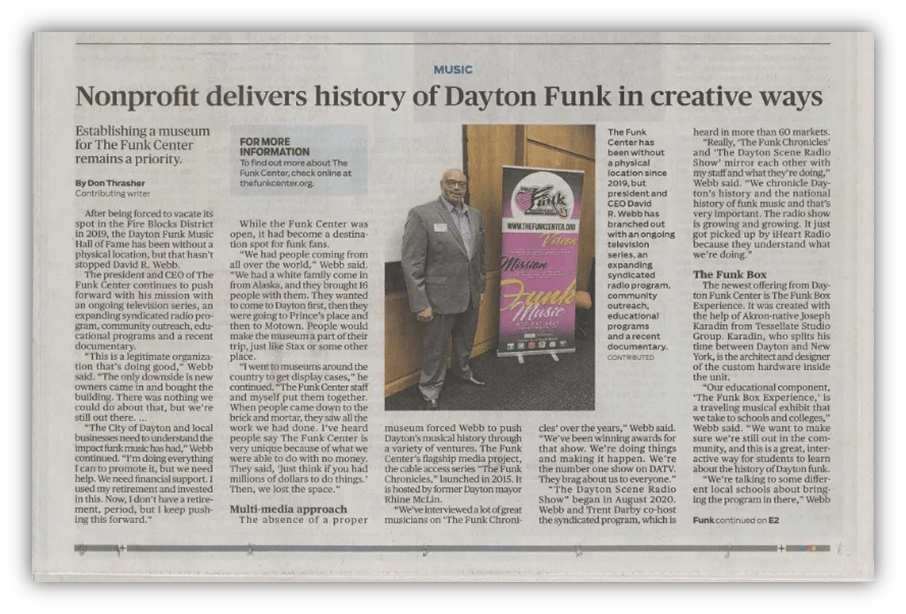

The epicenter of 1970s funk was Dayton, Ohio.

More charting funk artists came from Dayton than any other city. It was home to bands like Ohio Players, Slave, Sun, Zapp, Heatwave, Faze-O, and Lakeside.

Lakeside was named after Lakeside Amusement Park, and the roller coaster there inspired Ohio Players’ song “Love Rollercoaster.”

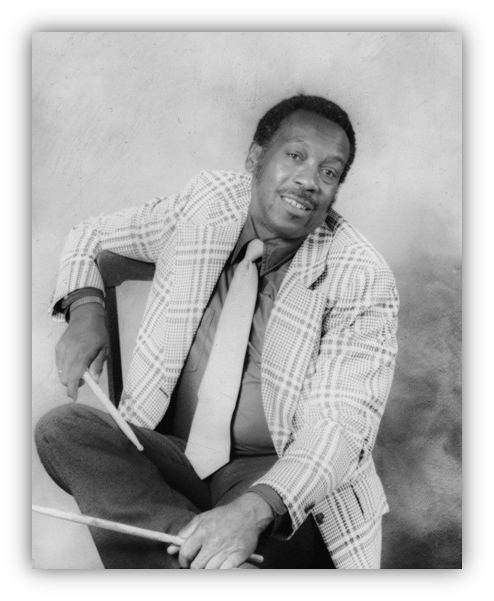

There’s an urban legend that it includes the scream of a woman being murdered outside the studio, but drummer Jimmy “Diamond” Williams said it’s just singer Billy Beck doing “one of those inhaling-type screeches like Minnie Riperton.”

No one’s sure how the rumor started but it spread nationwide when Casey Kasem repeated it on his syndicated American Top 40 radio show. Williams said, “The band took a vow of silence, because you sell more records that way.”

Not only did the Ohio Players remember their roots, they never relocated.

They stayed in Dayton and became mentors to high school age musicians there.

Likewise, Zapp started the Troutman Institute, named after the four brothers in the band. The institute buys and renovates low income properties in and around Dayton and offers low interest loans so people can buy their own homes.

Perhaps the most astounding thing a funk musician ever did for a city happened in Boston.

Boston was a segregated city. The Irish stayed away from the Italians, the rich stayed away from the poor, and the blacks had the South End and Roxbury neighborhoods. It was still that way when I lived there in the late 70s. Maybe any of you familiar with the area now can let me know if it’s any more integrated now.

On April 4, 1968 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. Riots broke out that night in cities all over the country, including in those black sections of Boston.

James Brown was booked to play at the Boston Garden the following night. But city officials worried that it would bring the riots into the downtown area. The police wanted the show to be canceled, but Mayor Kevin White knew that canceling or even postponing the concert would be seen as racist. That could make things even worse.

One of White’s assistants, a young black man named Tom Atkins, came up with the idea of broadcasting the concert for free so people would stay home to watch it there.

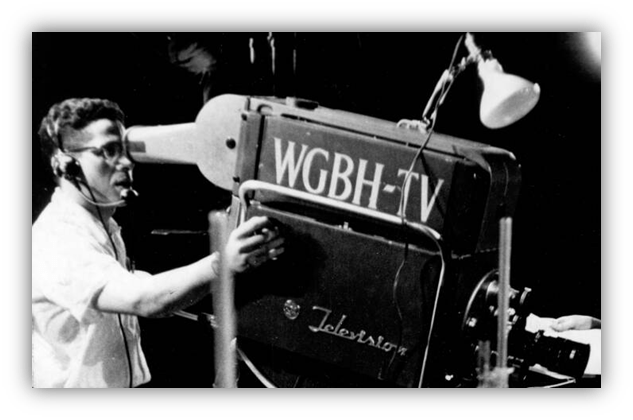

Brown didn’t like the idea because he thought people would indeed stay home, after returning and getting refunds for their tickets. He was going to lose money. And that was before they told him that it wasn’t just going to be on WGBH radio, but on WGBH television, too. He was very angry when he found out.

Brown and his manager said they were going to lose $60,000. The city told him they could come up with $10,000. Given the circumstances, they finally promised they’d find the rest somehow.

WGBH is the Public Broadcasting System station in Boston.

They were used to airing classical concerts and operas.

With no experience with louder, more varied instruments – and very little notice – they did their best to set up their equipment, hoping the sensitive microphones wouldn’t be destroyed by the volume.

The only hitch in the show was a tense moment when young black men from the audience started climbing on to the stage. The mostly white police were ready for violence and approached them, but Brown asked them to step back. They did.

Then he asked the crowd to get down off the stage. They didn’t.

So he schooled them.

“We are black!,” he told them. “Don’t make us all look bad! Let me finish the show. You make me look very bad because I asked the police to step back and you went and you wouldn’t go down. Now that’s wrong, that’s wrong. You’re not being fair to yourselves and me neither. Or your race. Now I ask the police to step back because I thought I could get some respect from my own people. It don’t make sense. Now are we together, or are we ain’t?”

The few people remaining on the stage got off. WGBH immediately repeated the concert. It was close to midnight by the time the second airing finished. Even protesters need their sleep.

There were no riots.

Technically and politically, the show and the broadcast were a success. More than a hundred other cities burned that night. There were riots and looting and 40 deaths. 20,000 people were arrested.

Boston was saved by an artist.

The event raised Brown’s profile nationwide.

Following the murders of Dr. King and Malcom X, he was as much a spokesman for black people as Jesse Jackson, Julian Bond, and John Lewis.

So he spoke his mind. He fought for civil rights, but he was also bothered by black on black crime.

Like he did on the stage in Boston, he asked black people to respect themselves. He told them to “Say It Loud (I’m Black And I’m Proud).”

Funk was surpassed in popularity by disco, but all those funk records reemerged in hip hop.

One of the most used samples is a few measures of Clyde Stubblefield’s drum break from James Brown’s “Funky Drummer.”

It’s an appropriately named song. And a reminder:

That we’re one nation under a groove.

Suggested Listening – Full YouTube Playlist

Out Of Sight

James Brown

1964

Soul Finger

The Bar-Kays

1967

Say It Loud (I’m Black And I’m Proud)

James Brown

1968

Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)

Sly & The Family Stone

1969

It’s Your Thing

Isley Brothers

1969

It’s My Thing (You Can’t Tell Me Who to Sock It To)

Marva Whitney

1969

Higher Ground

Stevie Wonder

1972

Superfly

Curtis Mayfield

1972

Theme From Cleopatra Jones

Joe Simon

1973

Up For The Downstroke

Parliament

1974

Pick Up The Pieces

Average White Band

1974

Love Rollercoaster

Ohio Players

1975

Play That Funky Music

Wild Cherry

1976

Riding High

Faze-O

1977

One Nation Under A Groove

Funkadelic

1978

More Bounce To The Ounce

Zapp

1980

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Great overview, Bill! I didn’t realize Heatwave had Midwest roots — I remember Casey Kasem saying something about a European connection? Anyhow, good to have you back in the saddle for season five.

You’re absolutely right. Heatwave was international. They had a Czech, a Jamaican, a Swiss, and two Americans, both from Dayton. Casey got the “Love Rollercoaster” scream wrong, but he got Heatwave’s origins right.

Also, two Englishmen. 🙂

‘West End… Stuttgart, Munich, Heidelberg…’ Yep, international.

Welcome back, Bill! It’s great to have the series back. Excellent work, as always.

That’s fascinating about Larry Graham’s bass playing. I’ve heard of bands compensating for a lack of bass guitar, but drums? No wonder his style was so distinct.

Anyone who hasn’t seen Alex Gibney’s documentary Mr. Dynamite: The Rise of James Brown should definitely check it out. I think it strikes the right balance between critiquing Brown for his tyrannical moments and praising him for his tremendous artistic and cultural accomplishments.

Zapp and “More Bounce To The Ounce” is leaning into electro

When I saw that there was a full video of the James Brown performance, I thought, “OK, that’s great, maybe I’ll watch a minute or so.” I went much deeper.

In addition to being a historical landmark, it was great show. And also fascinating to see a little bit of what was to become signature Michael Jackson and Prince moves, from the original source.

I remember being a kid and trying to flesh out what funk was. One thing that I thought defined funk was a circular bass line (if that even makes sense). Like a line that is played over and over, such as “Low Rider” or “Dazz” or even “My City Was Gone” by the Pretenders (which is not really funk, but might be considered funk-y).

But I’ve learned over the years that what constitutes as funk is often much more linear. That is, a song just gets on a groove and moves forward, often not featuring verses and choruses. A lot of James Brown songs get that way, certainly the Parliafunkadelicment Thang, too.

The funkiest song in my mind may be Rufus’ “Tell Me Something Good”.

Yes! Repeated bass and/or guitar and/or any instrument riffs set up that groove and don’t let it stop. It puts the funk in your trunk, moreso in your torso.

“Tell Me Something Good” is indeed first class funk. It’s worth noting that it doesn’t hit the 1 on the second measure, but the syncopation does the trick.

Good point…syncopation! Usually songs by P-funk (the ones that I’ve heard) don’t excite me much because they’re very linear, but not as syncopated. That syncopation is what makes James Brown and Rufus and others so fun.

Though having listened to “Up for the Downstroke” there is some fantastic syncopation going on there at a couple points.

I absolutely love it when artists turn the beat around so much that I can’t even figure out what’s goin on or where beat 1 is. I’ll repeatedly listen to try and figure it out and feel a bit of satisfaction when I finally get it.

There are a lot of pop and rock cover bands out there, and they can do a serviceable job on a tune.

When it comes to funk, there’s a lot more to it than just playing the notes. You can spot a mail-in job a mile away.

Here’s a favorite from a now defunct (defunkt?) band from Minneapolis. Featuring all-around good guy Saint Paul Petersen from The Time and Family, they pull it off with style.

https://youtu.be/awaHbn2pV80

Oh, so much to unpack here!

That’s for this article, Bill, you cover the birth and growth of Funk very well.

James Brown (you notice everyone calls him by his full name, no short cuts for the Man!”) was my main man in the ’60’s and while everyone else was swooning over Motown (myself included), I was drawn to the musician and his music and bought all of his albums.

Side note. When I went West for college, there was a significant number of

Black athletes on our football and basketball teams. When they found our I had a full collection of JB’s music, there was a constant knocking on my dorm room door of people wanting to borrow my albums.

When Clinton and the Parliaments hit the scene, I was taken aback and didn’t quite know what to make of their music.

Interesting enough, as I’ve aged, I find their music far more enjoyable now than 45 years ago. Such is (the Funky) life.

I finally got to see James Brown in concert in the ’90’s and it was tremendous and I even got to shake his hand!

Funky start to Season 5!

Side note: Anybody who watched PBS from the ’70s onward knows WGBH (or at least this music).

https://youtu.be/EUWygGsyCyY

For some of us, it’s immediately followed by, “Write Zoom! Z double O M, Box 350, Boston Mass, OHHHH two Onnnne three fooooouuuuur!”

I learned what a S.A.S.E. is from ZOOM. 😊

Good to have the series back! Excellent stuff as ever.

Reading James Brown’s tyrannical approach to band leadership put me in mind of Whiplash. Saw him at Glastonbury in 2004, by that point, in his 70s he spent as much time offstage with the band taking up the slack while he conserved his energy for short bursts of showmanship.

The photos of the Bar-Kays to Sly & The Family Stone to Parliament to Funakdelic is like an evolutionary scale from besuited respectability to far gone funking freakiness. All in a few short years.

This is a really good breakdown of a musical style I happen to love, and it was fun to learn about Dayton, Ohio and its importance to the 70s funk scene. Perhaps it was Dayton that Lipps Inc. aspired to as a destination in their #1 hit? Well, maybe not. I started compiling a funk playlist on Spotify 7 years ago, and have been slowly adding things to it, often thanks to Tom’s column, when he has mentioned a #1 artist’s roots in/as a funk band or talks about a funk sample used in a rap #1, which as you mentioned, gave new life and recognition to the genre. I think the contrast between Motown and funk music is a fair one, but despite efforts by Barry Gordy to appeal to the mainstream and soften the hard edges of the music on his label, I would also maintain that the general public was exposed to a lot more raw blackness on those records than many realized, particularly through what was going on instrumentally. The session players on those hits were often taking the grooves and styles they were playing in the black clubs right into the studio. Maybe there is a reason they were eventually known as “The Funk Brothers”.

Good point. The Temptations certainly went a little rogue.

Many years ago, in the age of Mosaic and HTML 1.0, I built The Motherpage, the first P-Funk reference on the World Wide Web, carving the 1s and 0s out of stone. It has been preserved, as if in funky amber.

https://mother.pfunkarchive.com/

This is absolutely amazing. What an artifact!

Behind the scenes, do you think it’s possible that Nat King Cole had one of those you’ve got to let Nat King Cole, be Nat King Cole conversations with his label?

Young Master Plow and I took a day trip last week to Hotlanta. I prepared a Funk playlist to listen to for the 2.5 hour trip each way. I ended up with over 200 songs. Needless to say, old school funk is one of my favorite things.

I would also recommend the following tracks:

Earth Wind & Fire

Commodores

Kool & the Gang

Billy Preston

BT Express

Charles Wright/Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band

Chuck Brown/Soulsearchers

Gap Band

Graham Central Station

King Floyd

Tower of Power

Spinners

You don’t see Charles Wright and King Floyd every day. Great inclusions.

Terrific playlist!

Nor Chuck Brown and the Soulsearchers. Excellent choices, Mr. Plow. Thumbs up to you and Young Master Plow.

Also, I didn’t know you were so close. Let me know if you ever get up my way. I’ll buy you a Goo Goo Cluster or something.

Does A Boy Named Goo / Dizzy Up the Girl / Gutterflower count as a cluster? If so, I’m in!

Not exactly what I had in mind, but it sure counts. Come this way and I’ll buy you a Cluster, too!

I hope you revisit this site, Bill.

Over the weekend, Serius/XM did a funk sound segment and with the usual

bands (Clinton, etc.) they added Rick James. You left off your list and it was too late at night to think of it.

I always remember James as a leading paragraph in “Sports Illustrated”

The author wrote ” The Portland Trailblazer basketball offense is like a Rick James song. Three minutes of rock and five minutes of funk”.

There goes VDog, once again defining a genre superbly where I had previously never thought to define.

“What is funk?”

“Er, it’s funky”

Thank you, good night!!

I can’t believe I never noticed funk primarily focusing on Beat One. Love it, makes total sense now. If you’d asked me prior to today what makes funk funky, I’d have said it’s a thudding, popping bass. And boy did BabyDutch love her some funk. It was so aggravating too as a youngling to find that funky music, I had no concept of segregated music stations and how there were supposed to be certain demographics that listened to particular types of music. It was just all wonderful, glorious music to me. One massive musical melting pot. But I definitely realized soon enough I had a preference for the various types of music being performed by blacks, and even questioned at an early age – how come white folks can’t groove like this?!

Dutch wants the Funk. Gotta have that Funk.

Excellent entry as always VDog. Nom-nom-nom…

Advisory – Dutch goes Duran alert….. 🙄

So back in 1985 when guitarist Taylor and drummer Taylor left Duran, the remaining threesome enlisted Steve Ferrone (formerly of the Average White Band) to be their unofficial drummer for the Notorious album. He came back for various songs over the next 10 years with them (that’s Steve on Ordinary World).

Anyhoo, once drummer Roger and guitarist Andy returned to the band in 2002, they had to learn all the songs Duran had done over the previous 17 years. I remember reading somewhere where Bassist John found it funny how flustered Roger would get trying to figure out Notorious and was like ‘how did Steve do this??!! I can’t play like that!!” He obviously found his funky drummer side once again soon enough.

But that always stuck with me – a drummer commenting on how another drummer’s tactics were seemingly out of his league. So yeah, definitely came to appreciate all of Steve Ferrone’s work over the years. 😁

That’s a nice bit of trivia I didn’t know. Thanks!