“U üü ü, schampa wulla wussa olobo, hej tatta gorem,

eschige zunbada, wulubu ssubudu uluwu ssubudu,

tumba ba-umf, kusa gauma, ba – umf”.

Hugo Ball, 1916

What responsibility does an artist have to the public?

The answer is…DADA!!

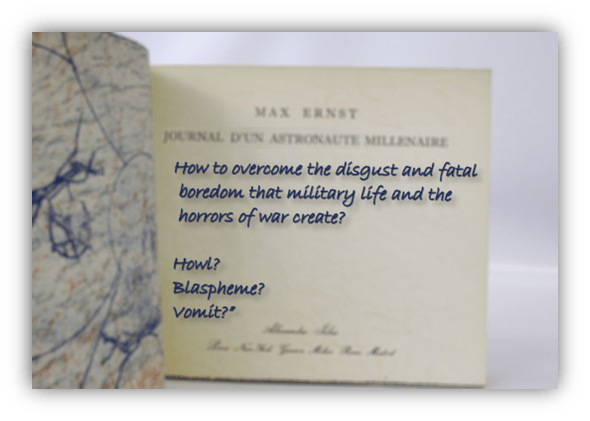

Reflecting on his service for the German military during World War I, Max Ernst wrote in his diary:

Several other artists across Europe were asking themselves similar questions at this time. And the answer for them all turned out to be: DADA.

DADADADADADDAAAADADADADADADADADAAAADaDADDADADAAAA!!!!!!

Sit down. I’ll explain.

While the Italian Futurists had tried to use avant-garde art to spark a great war, most other artists were horrified by the devastation that came with World War I.

Many did their part in fighting for their nations, as Max Ernst did. And upon witnessing what they felt was a needless, senseless, and tragically costly war consuming all of Europe, their ideals came to be shattered.

- They lost faith in the wisdom of their leaders, in the greatness of their respective homelands. They lost faith in the noble intentions of mankind, in the cultural systems that legitimized progress, including art.

- They lost faith in the power of human reason to dictate action. In short, they were revolted by what civilization had become and they wanted to burn it all down, or at least find a way to escape.

But they also knew that such dreams were futile. So upon finding each other, these artists decided to at least share some laughs together as they pissed on everything they could.

Dadaism had no one starting place, but the closest thing to an official start occurred in Zurich in 1916.

Switzerland had remained neutral during the war, and so it was the ideal haven for disenchanted ex-patriots to leave their nations and gather together. There, artists such as Hugo Ball, Tristan Tzara, and Andre Breton set up regular performance events at the Cabaret Voltaire.

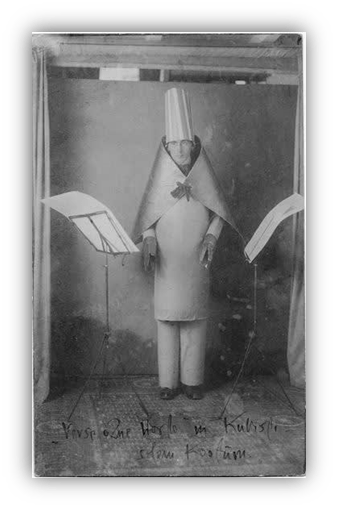

The opening event they hosted featured Ball dressed as a sort of pope in outlandish cardboard robes, reciting in unison with the others a chant of nonsensical sounds as a benediction for their new movement.

The club’s patrons, who had largely come for cheap sausage and beer, could not have known what to make of what they were witnessing. And that was largely the point.

Dadaism was a social art movement waged against society, and against art movements. In their raging against the failed ideals of reason and progress, the artists came to embrace the aesthetics of disorder and nonsense.

And had plenty of fun in the process.

Hugo Ball and Kurt Schwitters composed extended songs and poems of completely made-up words. Here is my favorite one.

Andre Breton wrote plays using actual words, but with plots and dialogue that made no sense.

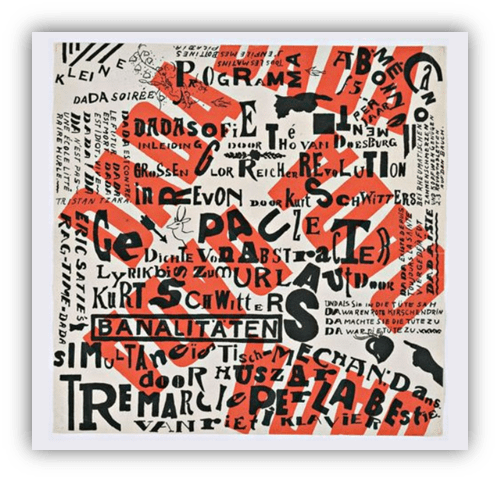

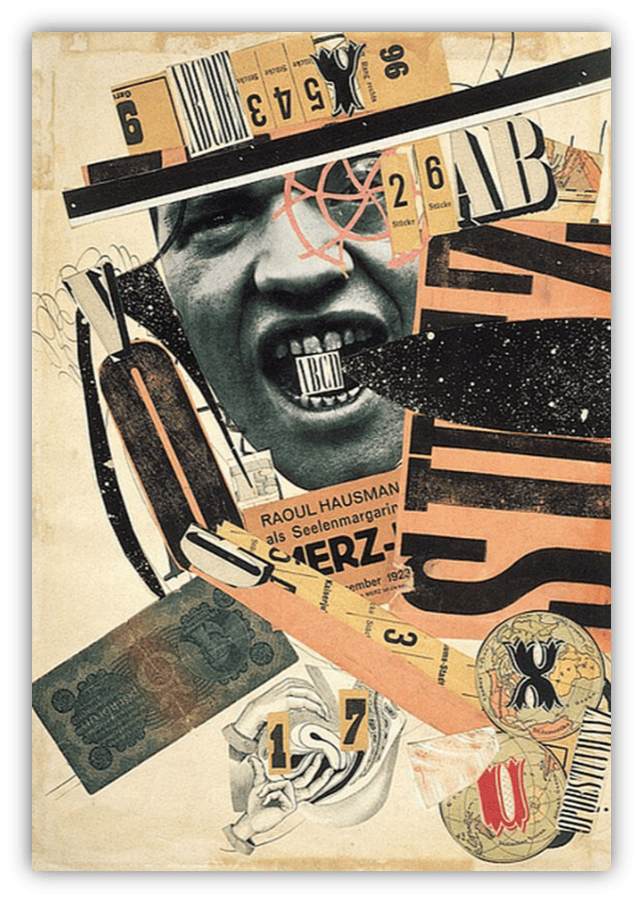

Tristan Tzara turned typographic printing into an assault on the eyes. Max Ernst, Johannes Baargeld, and Raoul Hausmann made photo collages that could be hilarious and/or nightmarish.

-Hausmann, 1923

Instead of painting, Schwitters assembled multi-textured works from metal, wood, and random objects…as well as paint, sometimes.

– Schwitters, 1919

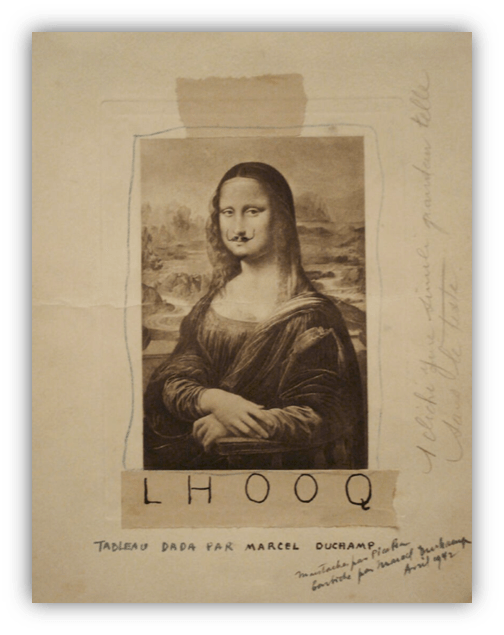

Marcel Duchamp made art from “readymades” such as a bicycle wheel and an old urinal. He presented these pieces at the Grand Central Palace in New York City as important new works.

And he defaced a picture of the Mona Lisa with a mustache and a raunchy French pun. Quoth Duchamp: “It’s art because I say it is.”

If the public had been resisting their suspicions that modern artists were playing practical jokes on them, here’s when all their suspicions were confirmed.

From here on out, art was nothing, and everything was art.

The anti-art of Dada wasn’t completely without precedent. There was a group in Paris called the Incoherents who formed in 1882.

They came from the Symbolist and Decadent circles of that time, but these artists were pranksters creating satirical works to dump on notions of beauty, taste, talent, and sense.

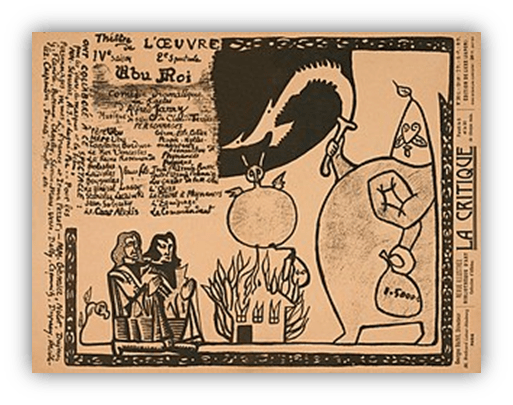

Alfred Jarry was a friend of the Incoherents, and aside from making the loud, silly, and profane play Ubu Roi, he pioneered collage art and typographic experiments that the Dadaists would hone to perfection.

Alfred Jarry was a friend of the Incoherents, and aside from making the loud, silly, and profane play Ubu Roi, he pioneered collage art and typographic experiments that the Dadaists would hone to perfection. Like Jarry’s infamous character Pere Ubu, there was more than a little childishness to the antics of the Dadaists. That was intentional.

They wanted to let out their inner brats and make the art world their playground for a little bit.

Some artists would eventually pursue these more intuitive dimensions of their works more seriously, but that’s a story for another time.

Like the Symbolist poets, there is nihilism at the root of this movement, and real despair.

But, there is plenty more to it than that. The work of the Dadaists is so often electrifying, full of life, despite the cynicism and irreverence. Through their dark humor, the artists were able to process their trauma and their feelings of powerlessness.

And they did so by banding together, in one of the first international art movements in history.

Far from bleak: that’s downright inspiring.

At the edge of the abyss, these men decided not to jump, but to let out a good fart and find out what it sounded like.

In the end, the Dada artists did not destroy the systems they hated, but their movement did at least allow them to vent.

And the art world was thoroughly transformed through their efforts, for better and for worse. “For the better” in that the radically unique and daring ideas of these individuals were eventually lauded and emulated. They redefined the art elite’s standards of taste and beauty, arguably far more than the Symbolists did.

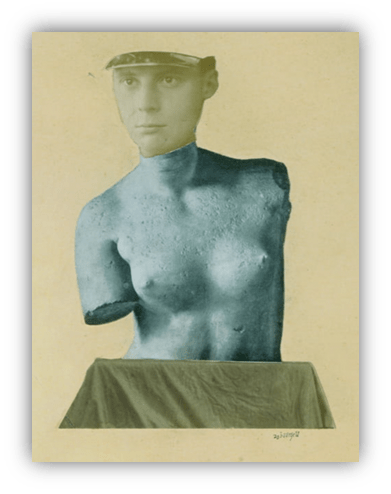

-Baargeld, 1920

“For the worse” in that even the cheap readymade products–heck, even replicas of Duchamp’s urinal piece–became commodities to be bought and sold for millions of dollars.

The system had indeed changed, but some rules seem to always remain the same.

(In my own spirit of snotty defiance, I say piss on that. And apparently Brian Eno agrees.)

From punk rock to art cinema, and even Monty Python, Dadaism paved the way for so much subversive countercultural art in the decades that followed.

Nowadays, at this late date, even popular music, television, movies, and advertisements show a debt to the movement.

Though it was defined by its rejection of normative culture, and was banned by authoritarian regimes as degenerate art, the rebellious spirit of Dada has since become thoroughly mainstream.

I fear that it’s the cynicism and the domineering impulsiveness that’s mostly been preserved and spread around. But hopefully some young artists out there are finding new ways to laugh at despair.

May they give the next generation a fart to end all farts.

And may it give them joy.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Is it wrong that upon reading this, the first thing that came to mind (and is sticking there, thanks) is https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=lNYcviXK4rg

Nein, nein, nein. It makes some sense, even aside from the name. The song and video have a crude DIY aesthetic that probably owes an ancestral debt to Dada.

Though maybe they would have said that it’s too catchy, too professional, and its lyrics make too much sense?

I hear you, Chuck.

Trio came this close to making an appearance in the teaser.

You’re not the only one. It provided the soundtrack to my reading as well.

De do do do, de da da da is all I want to say to you.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ZHpLyas01A

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E2lEoiDtRkc

https://youtube.com/shorts/Ua6tI6ZrVo0?si=zn2o6C-mAdb8HZ0w

And here we get to the heart of it.

💕

That was what was running through my head the whole time I was reading.

Oh, boy. This takes me back to German lab. The teacher played us its parody song, too, called “Ya Ya Ya”.

I was going to add some photos from my recent trip to Paris, but it seems the files are too big to upload.

Just Google “59 Rivoli Paris” to see the various images of a more recent incarnation of the Dada spirit.

Beyond those artists, I found that anarchic humor to be littered throughout the city of Lyon–though no area more than the Croix-Rousse district, where we stayed. The graffiti there is very knowing, clever, and mischievous.

That Kurt Schwitters poem sounds like a deranged Scotsman speaking in tongues. I can hear in that an influence on Spike Milligan who was a precursor to and in turn a big influence on Monty Python and had a strong surrealistic streak.

It’s a shame that the output of the movement has been co-opted into being commodities but its always going to be the way that success will influence others. Whether in a positive manner by encouraging creativity in others or being diluted for mass consumption or to make money. Your assertion of the movements it has paved the way for shows that regardless of any negatives it has had a massive positive influence.

I don’t know Spike Milligan, but Monty Python is a great example of Dada humor gone mainstream. And Terry Gilliam’s animated sequences seem to pull directly from what Max Ernst was doing with his collages.

https://youtu.be/BmJSrVNKnr0

Spike was part of The Goon Show in the 1950s along with Peter Sellers for which Spike wrote much of their material. He then wrote books and had his own sketch show; Q from which it was one short step to what Python did.

He does also have a small role in Life of Brian, he’s the guy left alone at the end if this scene;

https://youtu.be/Ym-k5viJ7tA?si=W05LyVoA3tdmikNv

This is one of his greatest moments though. King Charles was a big fan of The Goon Show. Receiving a British Comedy lifetime achievement award in his 80s, Spike uttered this put down;

https://youtu.be/4_iLElHqv-w?feature=shared

Here’s what some more recent neo-Dadaists have to say about mass consumption.

(Very much NSFW)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hJ9yBgTp9UQ

I get the feeling that Dadaists would happily flaunt being NSFW.

Oh, sí Señor…though the next wave these artists took part in was even more so.

Wut?

I drew Max Ernst’s name out of a koa wood bowl. He was the subject for my oral report in English. I looked for two examples in popular culture that would be familiar to the whole class. I used the scene in which John Malkovich enters his own portal, and Conan O’Brien’s “If They Mated”.

I mostly talked about collage.

For the sake of art, I cut up about fifty-to-seventy-five CD covers. I called it Mash Your Taro on the Indie Rock.

Family Ties couldn’t be less dadaist, but Gary David Goldberg’s production company was called Ubu Productions. Never made the connection ’til now.

“Sit, Ubu, sit, good dog.” Presumably, Goldberg.

(woof) Presumably Goldberg’s dog.

Mike Judge’s Idiocracy?

Absurd enough to be dada? Or just low-brow comedy?

That “Sit Ubu sit” line is always roaming about in my head.

The band Pere Ubu took their name from that titular main character of Jarry’s play.

Not to mention, Blixa Bargeld named himself after Johannes Baargeld. To say nothing of Cabaret Voltaire.

And Kurt Schwitters happened to call his take on dada “Merz,” and he constructed his own studio, called the Merzbau. And a certain Japanese noise artist liked that as a name, though spelled as “Merzbow.”

You can actually hear Schwitters doing his nonsense song on the Eno song “Kurt’s Rejoinder,” which is named after him.

Idiocracy? I don’t think it is itself Dada. But as a satire it’s so incisive. Perhaps what you’re honing in on is how the film shows the ways in which our society is becoming cruder and coarser, like a whole nation of Ubus. I find that more horror than comedy!