“How are you doing?”

It’s a question we often ask without really wanting to know the answer.

We usually want to know what someone has been doing with their time. What exciting updates do they have to share? A promotion?

A vacation? A crazy adventure?

A new TV show to recommend?

To be fair, it’s hard to answer the question of “how are you doing?” if you want to do it right. Our lives are complex, with so many layers to them. And each layer is subject to change, and so is subject to uncertainty.

How am I doing?

It depends on what you want to focus on. And maybe also on what happens next.

No wonder we usually opt for a safe, superficial response like:

“Doing good, man. How bout you?”

And leave it at that.

In a series I wrote for tnocs last year, I tried to convey my personal experience with intercultural exchange in terms of the different layers that made up the experience.

I started with the typical dynamic of someone studying abroad, then moved to longer-lasting relationships with foreign students including my wife. For my closing chapter, I switched to a more painful layer of challenges that had emerged in our relationship over the years.

Because my aim for those entries was to focus on intercultural issues, I had to do some heavy filtering of my recollections, even for that deeper layer. Here I will try to convey yet one more layer of our lives together, one that almost never gets relayed to others when they ask us “How are you doing?”

It’s the layer that concerns our daughter.

Following my return from study in Tokyo in the spring of 2005, the two of us waited long-distance for several months before we could see each other again.

Then she came to study abroad in Philadelphia, and we got to act like a typical couple in love. At least until she had to return home.

During this time together, I was finishing my undergraduate degree, working part time, studying for the GRE, volunteering in a research lab for experience and recommendation letters, and applying for doctoral programs in psychology. She was deep into her undergraduate studies, taking classes in English and learning all about America and Philadelphia.

It was a busy time, full of anxious uncertainty. But it was also the honeymoon phase of our relationship. And that was lovely.

Not long after I accepted an offer to enter Penn State’s grad psychology program, I asked for her hand in marriage. We both agreed to wait for five or more years living apart, until I could sponsor a fiancée visa for her return.

It was a painful, crazy, and resolutely romantic decision to make.

I imagined the two of us telling this romantic story to others later in our lives, how we finally came together. And that image helped me actually endure those years apart.

What I did not imagine is that, shortly after leaving the US, my wife would let me know that she was pregnant with my child.

We had indeed been acting like typical young adults in love during our time together in Philly.

Including not always being careful with protection during sex. Just a few seconds worth of negligence, and our lives were ultimately changed forever.

Even so, we both agreed on one thing: that we were not ready to be parents at this early juncture. She had just left the US for Japan. I was finishing things up at my part-time job and was preparing to move to central Pennsylvania for five or more years in graduate school.

Our adult lives were just starting to take shape. How could we raise a child in such a state?

We didn’t want to push our resentments onto our child, like her parents had done to her. We wanted more stability, more time to prepare for such a heavy undertaking.

We agreed that getting an abortion was the best option to take. It made sense then, and it still does now.

But the best option was not by any means a good one.

We decided to go through with it.

To do so, we needed money. And we needed official written consent from both parents to permit the procedure, per Japanese law.

Having very little of my own money, I had to borrow a few hundred dollars from my brother and from a friend. In order to pay them back, I stayed on my part-time job for a little longer.

I worked ad hoc at Tower Records as well, as many hours as my old boss would give me.

I received the permission form in the mail from Japan, and I put my signature and thumbprint on the document to affirm my consent to the abortion. I sent the form and the money to Japan as soon as I could.

We also arranged for me to visit her in Japan right before I would leave for Penn State. There was no time to be there for the procedure itself, but I at least wanted to be there afterward. If only for a few days.

Whatever I could do to support my fiancée during this crisis, I did it. But what I could do was not nearly enough.

I was stuck halfway across the world from the problem at hand.

And so I took in what was reported to me after the fact, either by email or by Skype.

I could only wait, and hope for the best.

My fiancée emerged from the procedure physically fine, which was a blessing.

But that’s where the blessings had ended.

For starters, it turns out that she had gone to the clinic alone. She didn’t dare ask her family or even friends, for fear of what they might think. Abortion is legal in Japan, but people don’t talk about such matters with others. There is a heavy threat of judgment and shame for going against the natural order of things.

She got a taste of that shame from the doctor and the nurses at the clinic.

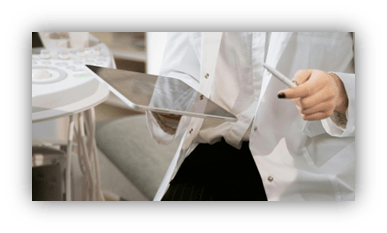

It’s required for women who want abortions to view the ultrasound of their developing baby before going through with it. She had to gaze at a blurry image of the life growing inside of her. A girl, she felt in her heart. And then she had to affirm that she wanted to terminate that life. The doctor looked at her with disgust, but started to prepare for the procedure. The nurses too looked at her with some mixture of pity and contempt as they readied her for the operation.

She went there all alone. She was browbeaten by her caretakers. She was violated, physically and mentally. She endured it all alone. And then she had to take a bus and a train back to her parents’ house. Groggy, grieving, ashamed, in pain.

And all alone.

Even now, almost twenty years later, my wife is haunted by that day.

Any show or film with an OBGYN clinic that looks a certain way will trigger stress memories of the procedure.

She still lives with the grief and the guilt of the abortion, of the life that we opted to have taken from her.

And the fact that I was not there when she had to endure that nightmarish experience still haunts me. At a time when help was most crucial for her, I could not be there. I had never felt more helpless, and useless. And, in my own way, all alone.

I was able to visit her in Japan a few months later, and we went to a shrine together as some sort of ceremony for our deceased child. But there was no real closure. There wasn’t even much disclosure. It was all too raw.

Instead, we looked ahead to the future. We committed ourselves to our five-year plan for graduate school and a fiancée visa. And we intended to honor our daughter’s memory by raising a family when the time was right. That seemed to be enough.

Little did we know, the right time would be a long time coming.

My career in research required extensive training and development before I could settle down and start saving money.

I started undergraduate courses in 2001 and I got my first steady position in 2016, nearly fifteen years later. An awful long time to be in professional limbo.

And throughout my time moving around as a postdoctoral fellow, my newly immigrated wife had to come along for the ride.

She had to sacrifice her own career dreams for a while, until we settled in Virginia.

Then it took some time for her to assimilate into the culture and to find a job that was right for her.

If we could have continued living in Montreal after my postdoc there had ended, we likely would have tried for a baby sooner. But alas, we settled into one of the priciest areas in the US, where daycare is another month’s rent. For all of those reasons, it took many years for us to actually feel stable.

Still, despite our cautious dispositions and our special circumstances, we built up enough stability in our lives to take a chance on the prospect of parenthood.

We were ready to go down that road just a few months ago, in fact. My wife and I promised one another that we would try for a child for one year and see what happened. Whatever would be, would be.

We promised that we would try…so long as Donald Trump didn’t win the election, of course.

Well, we all know how that turned out.

How am I doing now, you ask?

Not great, to be honest.

I’m sure plenty of people still skate by with B.S. non-answers to that question even now, but it’s a lot harder to do so when you live so close to the lion’s den.

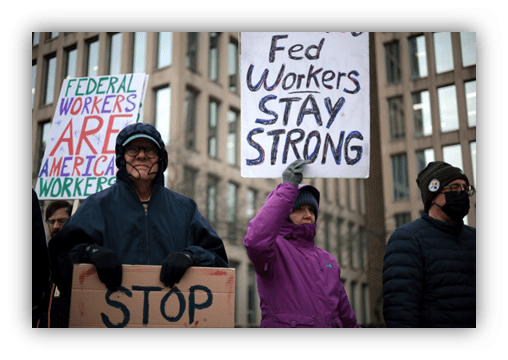

My work is now chaotic, and often demoralizing.

Additionally, like many other federal workers, my team has been deemed eligible to be converted into a fire-at-will political appointment.

We have filed for an exemption for solid reasons, but there is little faith that the administration actually cares about solid reasoning when it contradicts their will to power. We’ll see how it goes.

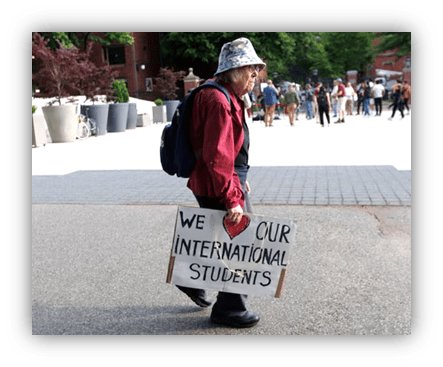

My wife works as an advisor for international students, so her job is full of new stressors and outrages as well.

Our visits to neighboring DC get more and more unnerving as the display of fascist occupation grows more and more blatant.

We’re trying to be positive despite it all, but things feel really bleak. And stressful to boot.

How is my wife doing?

She is trying to come to terms with the fact that she may never have a child.

She is fast approaching 40, when childbirth and development start to grow more difficult with age. Given my job situation and the chaos elsewhere—not to mention this administration’s cruel disregard for maternal health—we won’t be trying for a child any time soon.

But to never really try, to risk missing a biological deadline…that would be a major loss. Especially given our earlier choice with respect to our daughter.

My wife wants to right the scales somehow.

To balance out our decision to cut parenthood short with an earnest effort to have a baby now that we’re ready. At least try for one. But now she has to try to live with the possibility that it might not happen for her.

I don’t have to think about my own fertility, because men don’t have the same concerns that women do. I’ve never had a raging urge to have a child dominate my thoughts, as many women do.

And as horrified as I was to hear about my wife’s experience at the clinic years back:

I never had to live that experience.

She had to live it, and she has had to live with it for all these years.

“My body, my choice” is said to empower women, but sometimes it feels like a curse. Whatever choice is made, most of the weight of it falls on them.

How are we doing?

We’re doing as well as we can.

- We’re taking things day by day.

- We’re both seeing counselors to help process everything.

- We’re trying to be honest about the pain we’re feeling.

Not just from some new life chaos, but also the pain that stems from years past.

As for children, we will have to see what happens. We need to be realistic given our circumstances, but we shouldn’t needlessly give up hope either. Adoption may be another option to consider.

Whatever happens, we’re trying to properly grieve the daughter whose future we decided to cut short. We want to do her memory justice. This entry is one small effort in that respect.

Life is so much more than what can fit into the stories we tell about ourselves. Here is a layer of our lives that seldom gets mentioned, but it colors so much of what we do.

Our country has grown sick from its addiction to easy fictions over reality. Being open and honest about our life trials is one small way to resist that sickness.

And hopefully, by doing so, to eventually heal.

Wow. What a brave piece for you to write, and to share with all of us, Phylum. Kudos to you and your wife for being so open with sharing your stories of present and past, all of it adding up to a complex response to “How are you doing?”

I must admit you have been in my thoughts often since 45/47 was re-elected. I am glad to hear that you still have a job. I wasn’t sure at all. At this point, I don’t know whether having a federally connected position or no longer having one is the less fraught option.

I really appreciate the time and thought that it took for you to compose and present this. And, of course, the strength that the two of you have had, in living it.

Take care, my friend.

Thanks Chuck. I hope you’re doing well despite all of this chaos.

“Our country has grown sick from its addiction to easy fictions over reality.”

I’ve never heard it put so succinctly. I’m glad to have you back.

This is a riveting and heartbreaking piece. It lays bare the truth of abortion and demolishes the conservative talking point that liberals get abortions for fun. It’s a really hard decision, a permanent one with permanent consequences. You did the right thing, but even the right decision might not feel like a good one.

Thank for writing and sharing this piece, and please give yourself and your wife hugs from everyone here at TNOCS.

Thanks Bill. Yes, and it also challenges at least the easier liberal notions that having a choice is the beginning and end of the issue. Dealing with the choice is another matter.

Its good to see you back here even if its in far from ideal circumstances. This was a tough read but sometimes its good to be confronted with raw honesty and the reality of how difficult political and personal decisions can affect us.

Its human instinct to try and find something to say that would help but sometimes there isn’t anything. All I can say is I appreciate you bringing this to us and can only hope that the two of you find a way through all this.

Thanks JJ. I appreciate your support.

Phylum, I wish you and Mrs. Phylum the best in these difficult times. As my son is now in college, I may have some authority to say the parenthood journey will be imperfect, no matter how well you think you have it planned. Mistakes will be made; difficult times will be passed through — I can guarantee you this. So if parenthood is important to you as a couple, it’s going to require a leap of faith in the face of uncertain times (times are always uncertain, we just sometimes fool ourselves into believing otherwise). If you wait for perfect timing, the opportunity may pass permanently or the likelihood of complications goes up dramatically (women near 40 are much more likely to have a healthy pregnancy than women near 50).

Not that my opinion matters for anything here. I just want you both to be well first and foremost. But waiting for some sublime level of stability before committing to parenthood is an illusion. If you want it, go for it, and trust yourselves to do what’s best for the family.

Thanks Pauly.

I guess we still have to ultimately suss out the notion of “if parenthood is important to us.” Stepping aside from the reasoning, I think the fundamental driver of how someone approaches parenthood is a root feeling, or affect. Like, I knew postdocs who had job instability, and they had kids. Because they really wanted to have kids, no matter what. We don’t seem to have that.

I don’t know what drives the difference, but I am assuming the fact that my wife and I both witnessed our parents being miserable together during our adolescence had something to do with it. Her parents were resentful and sometimes violent, my parents were more restrained, but they slow burned into a divorce when I was in high school.

Without that deep-seated feeling of “I want this no matter what,” it very much becomes a matter of risk assessments. We want to feel secure enough to provide, and yet our bar is likely higher than some. As I said though, this is complicated by my wife’s enduring guilt about the abortion, and a need to set things to rights, which can sometimes be heightened by hormones. But she is well aware that her guilt is no good reason to be a mother, and may well not change anything on the guilt or grieving front. So, we are currently sussing out what we want and what risk we’re comfortable with. But we likely will never have that “I want this no matter what feeling,” so it will require more deliberate conversations and thought on what to do and when.

P of A, I’ve been grumbling about walking around on a sore knee the past couple of days. Thanks for putting that in perspective for me. I will now stop with the self-pity. So brave of you to share.

A sore knee can sure make you miserable. Hope all is well sg.

What a heartbreaking ordeal for your wife and yourself. Sometimes there really are no good choices. The only response I have to someone sharing at the level that you did today is “We hear you. We are here for you. We care.” I feel honored that you would share this with us.

Thanks, ltc. I really appreciate it.

Those are some tough times, Phylum. I hope there’s a happy ending, whatever that will mean someday. Thanks for sharing.

Same for you, Link. Hope your job hasn’t been too dramatically impacted by recent events. My local leadership decided to compete withTrump on sloppy, dramatic, and cruel hubris, but hopefully it’s not a common phenomenon.

Ugh..that is miserable. No, my local leadership is great, so that helps.

I do see a light at the end of the tunnel. It hinges on one person speaking out. That first domino has to tumble. Two online journalists are reporting on a long-dormant story. Snopes, a fact-checking site, wrote at the time of the event, that the story had no merit. I trust one of the two journalists. A fact-checking site shouldn’t get to be the judge and jury, and you just accept it as the truth. But admittedly, she hasn’t found proof…yet. She does, however, point out how the story just disappeared, even though it got coverage from major outlets. One issue, literally, one issue, I think, has the potential to unite the country. Somebody out there, if the story is true, needs to speak soon.

I hope everything works out for you and your wife, Phylum.

I learned something new about Japan. The patriarchy sucks.

Hail, hail, Valerie Solanas.

Wow. What can I say to add to what’s already been written here? Only that this is one of the most powerful personal pieces I’ve read anywhere. There’s a lot to absorb here, but it’s all worth the effort. And Phylum, my heart goes out to you in the situation you find yourself right now. I strongly believe that somehow you’re going to come out ahead in the end.

Sorry, Phylum, this is off-topic. But I want your take(and anybody else’s take is welcome) on what I think is the heart of darkness as to the past ten years.

The Goldwater Rule.

I know who the original Cassandra is. She edited a book. She appeared, once, on a cable news show. And then the APA cracked down on her. That’s why you don’t see medical professionals from the psychiatric field on television. You can’t discuss medical terms. You can use offshoots of the medical terms in adjective form. This keeps me up at night. If the medical term was used, maybe, people would look it up and discover who else shares the same psychological malady. And maybe they’d think twice about who they’re voting for.

A former ESPN anchor has his own podcast. He is a take-no-prisoners sort of guy. But even he abides by the APA’s rules. He speaks in code. I can read the code. He was referring to the president by another name, a person who may have the same problem. Clever piece of fiction. He/she fictionalizes a notorious criminal and his exploits from the seventies. But the reader understands this period piece is actually cosplaying; it’s contemporary. He most definitely read the book. The type of women he dates is in the title.

In the last week, or two, one of the news aggregators slipped up. There is a second medical condition the president may be suffering from. The article was about two psychologists(they don’t say where they’re broadcasting from) who regularly ignore the Goldwater Rule on a podcast supported by a “New Media” network. (The main figure uses this term, not independent media. Think of this network as the Marvel Universe.) The aggregator ran the story. The White House went nuts. They’re not used to journalists drawing attention to what is self-evident to any viewer who watches press briefings in its entirety instead of brief ten-to-fifteen second soundbytes of lucidity.

Did the media misinterpret the Goldwater Rule. Doesn’t that only apply to people in the medical field. Why can’t an anchor use the term?

I think we’d be in a different situation today if somebody risked his/her job and defied their network’s corporate overlord. And said the words that every prospective voter in 2024 needed to hear. But there’s no use whining about it now, even though I’m whining.

You think it would make a difference? The entrenched would howl that truth-teller out of his/her job, and reasonable would already know. Who has the authority to make that call, say it out loud in a public forum and have enough people trust it to make even a tiny dent in the status quo?

My fear is that the economy really has to fall off a cliff (we’re heading there pretty rapidly) to wake up enough people to make a difference. Then of course we will all be worse for the wear.

In Australia, a real-life Succession drama was playing out. You had the eldest child and father dueling with the two younger children. I wonder if some compromise was struck. I’m a little surprised by where the original reporting for the latest scandal is coming from. I know there is a news gathering division and an op-ed division, but still…I’m surprised. The father owns an empire. It looks like he’s fighting himself. But maybe, it’s his kids, presuming that the two younger children have benevolent intentions, who wants to steal the throne from their elder.

I’d like to think that the true believers would listen to the patriarch if he laid out his business model. But I guess I’m being naive.

When I explain that the divide isn’t entirely black and white to Hawaiians(I mean, people who look like me, because the president is very popular with Polynesians), I get push back, accusations of both-sideisms are made. I tell them, stop getting hung up on labels. If you’re voting for crypto, in my opinion, you’re aiding and abetting the potentiality of a kleptocracy.

I stopped going to rallies.

I agree with Pauly that at such a late stage of entrenched epistemic/media tribalism, such declarations likely wouldn’t have and won’t make a difference.

Maybe early on in 2016, when he was just an underdog novelty, how he was covered (or not) could have made a difference. Just as how he was countered by his Republican opponents could have made a difference. But we keep finding that many people seem eager to break Tim Snyder’s Rule # 1 about fighting tyranny: Don’t Obey in Advance. Courage can be contagious, but it won’t be if cowardice reigns. The resistance needs to be collective and coherent, and individual acts of defiance won’t mean much.

For me, the heart of darkness of this era is the exacerbation and culmination of something that Theodor Adorno noticed all the way back in the 1930s. How neoliberalism and mass consumerism hollowed out our culture and softened our citizenry to the temptations of fascism.

This piece still rings true for me:

https://tnocs.com/the-series-finaledude-wheres-my-van-part-21-heart-and-soul/

I worry about a Ministry of the Arts sort of situation. You submit your project and wait for approval from a committee.

Zhang Yimou’s films used to travel. I thought he retired. As it turns out, he’s an active filmmaker. It’s just that his subject matter has grown more conservative. You don’t get the cool coded films of his early years, or even his cool coded wuxia martial arts films of his middle years.

I recently watched two Walerian Borowcyk films through the Criterion Channel. On our current trajectory, I’m afraid we’re going to lose the freedom to access such material. They’re not capitulating. Arrow Films, on the other hand, don’t release trashy B-movies anymore, seemingly. The horror films made available at Barnes and Noble are old titles. Arrow wants to stay in business. Once and awhile, an out of print title shows up at Book Off. I usually ask the clerk to save it. I’m selling off my CDs. And I return with a medium size box.