You’ve seen it a thousand times.

It’s a contraption made of metal rods and sometimes leather, and holds a harmonica in front of your mouth.

It allows you to play harmonica while leaving your hands free to play guitar, piano, or any other non-wind instrument.

Photo credit: harmonicalessons.com

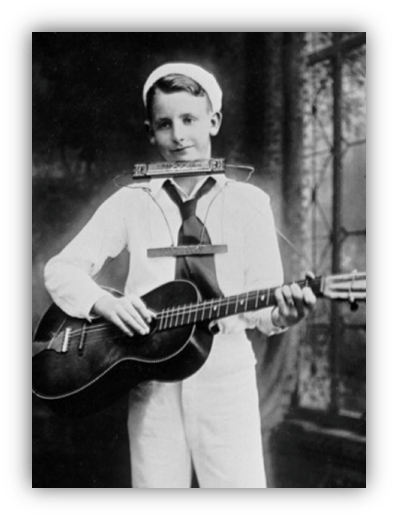

It’s simply called a harmonica holder and Les Paul is credited as its inventor. It was his first invention.

He was 12.

Now, such devices probably existed already. But he made his own, out of a wire coat hanger and pieces of wood.

What was different about his is that he had a two-sided harmonica — each side played in a different key — and his holder could easily flip the harmonica from one side to the other. He definitely invented that.

Did I mention he was 12?

At 13, he was a semi-professional musician.

He didn’t dropout of school to play music full time when he was 17.

He performed under the names Red Hot Red — which his mother suggested — and Rhubarb Red, both based on his red hair, but his birth name was Lester Polsfuss.

While harmonica was his first instrument, he also played piano and banjo, and he gravitated to the guitar.

Some of his early performances were at drive-in restaurants around his hometown of Waukesha, Wisconsin. These were outdoor gigs and he wanted to be heard by the people eating in their cars. He used the mouthpiece from his mother’s telephone as a microphone and amplified it through her radio.

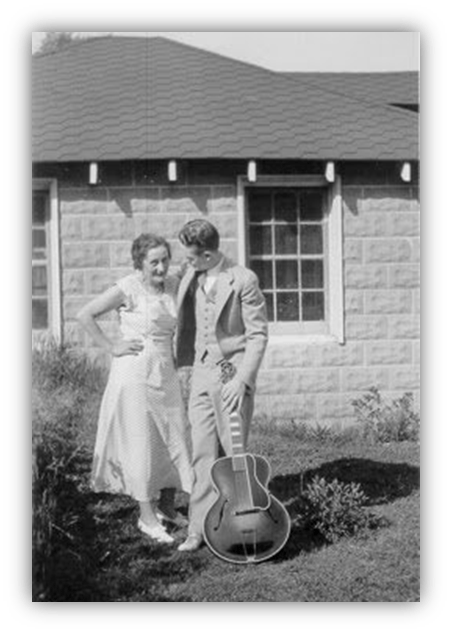

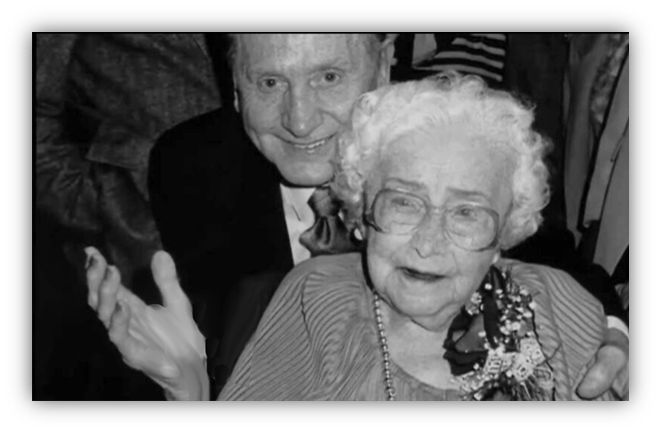

Les was close to his mother, Evelyn, who was a piano teacher.

His parents had divorced when he was 8, and both his father and older brother weren’t around much. He felt their absence and threw himself into music and, later, into his work in guitar and recording technology.

So Evelyn was more than understanding when Les wanted to experiment with her telephone, radio, and other gadgets. She always encouraged his music and curiosity.

He later said that curiosity started with the phonograph and player piano in their living room. If he sped up the player piano, the song’s pitch didn’t change, but it did if he sped up the phonograph. He asked himself why, and the rest of his life was spent trying to answer his own questions.

Anyway, listeners at the drive-ins said they could hear his voice and harmonica with the new equipment, but now they couldn’t hear his guitar.

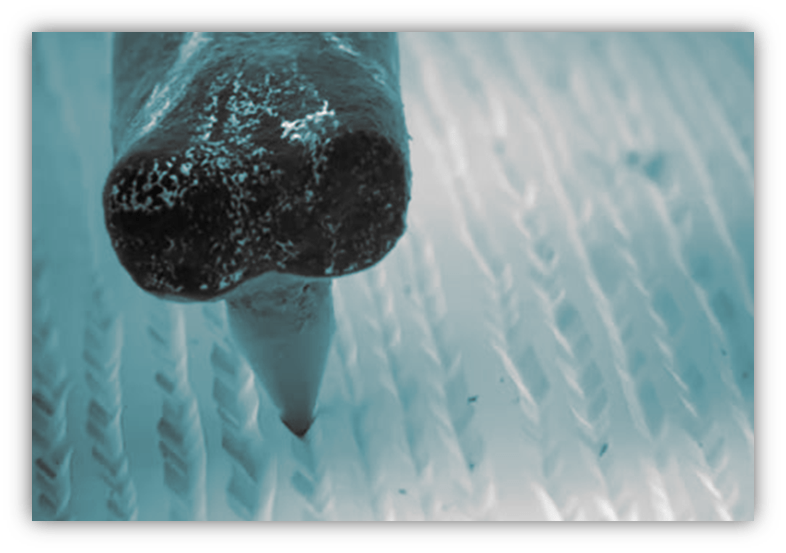

Les thought about it and realized that if a phonograph needle can pick up the vibrations in a record’s groove, it would probably pick up the vibrations of his guitar.

So he dismantled a record player — maybe his mother’s, maybe someone else’s — and stuck the needle to his guitar’s bridge.

It worked too well.

Not only did it amplify the notes he played, it amplified everything the guitar touched. If his arm brushed the guitar body while strumming, the sound of his sleeve against the guitar got amplified. Every little knock of his wrist or knuckles came out of the speaker. It even amplified the sound of his shirt against the back of the guitar.

He tried dampening the guitar by stuffing a towel into it. That helped but not well enough. He tried more towels, and then an entire tablecloth.

He finally filled it with plaster of Paris. The guitar broke.

That didn’t stop him.

He realized what he needed was a guitar with a solid body and a microphone that would pick up only the sound of the strings.

Prior to George Beauchamp’s invention of the guitar pickup in 1931, all guitarists trying to be louder faced the same problem.

When he and a friend were at some nearby railroad tracks, they found a two foot long section of rail. He took it home and figured out how to run a string down its length.

He placed his mother’s telephone mouthpiece under the string and plucked. The string sang through the amplifier forever.

The rail was so solid that it didn’t react to any motion around it, and the string vibrated uninterrupted. He showed his mother, and she pointed out that a rail would be too heavy to play for any length of time. He kept experimenting.

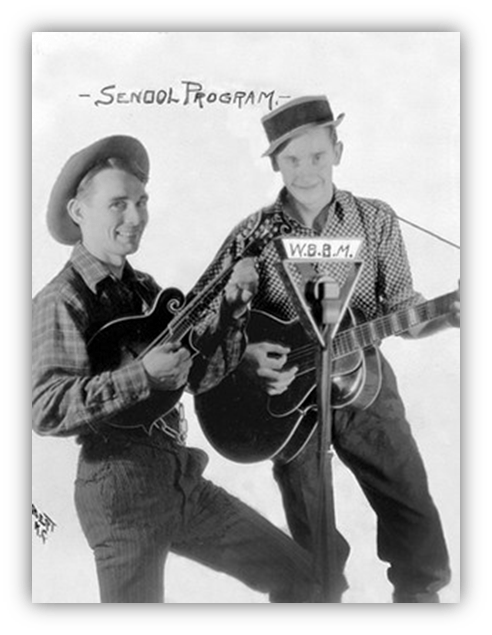

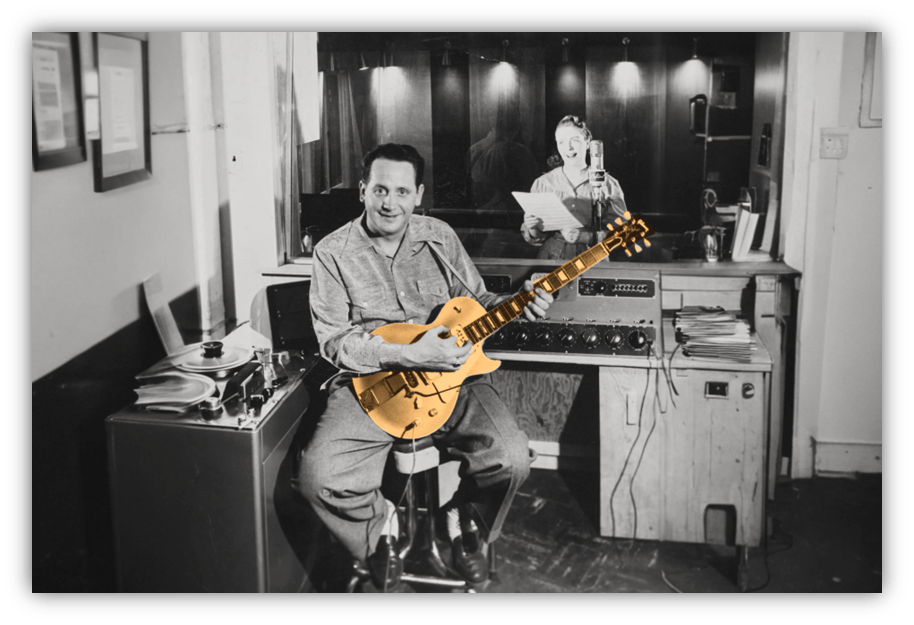

After dropping out of high school, he joined Sunny Joe Wolverton’s Radio Band on KMOX in St. Louis.

He later moved with Wolverton to WBBM in Chicago.

The band played Country music, as Les had done up until this point.

But Chicago had a strong Jazz scene. This is when he started using the stage name Les Paul. By day, he was Rhubarb Red playing Country on the radio. By night, he was Les Paul playing Jazz in the clubs.

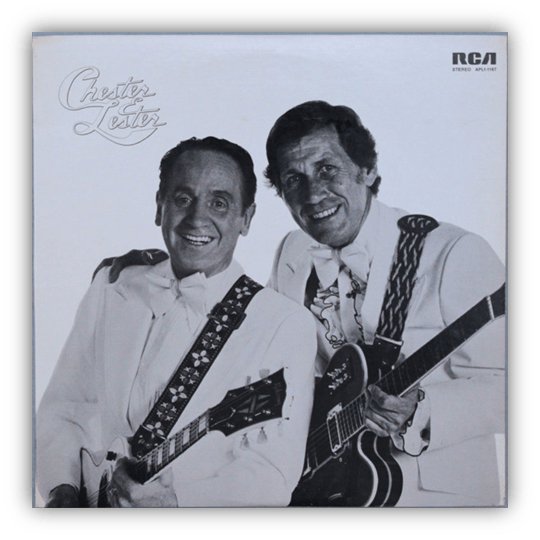

He formed the Les Paul Trio with two of the Jazz musicians he had met. The rhythm guitarist was Jim Atkins, who was the half-brother of guitarist Chet Atkins. Chet and Les would later become friends and release two albums as Chester & Lester.

The first record won the 1976 Grammy Award for Best Country Instrumental Performance.

In 1938, the trio moved to New York City to be regulars on The Fred Waring Show, a radio show that was syndicated nationwide. Paul became friendly with workers at the Epiphone guitar factory in Queens, and they would let him tinker after hours.

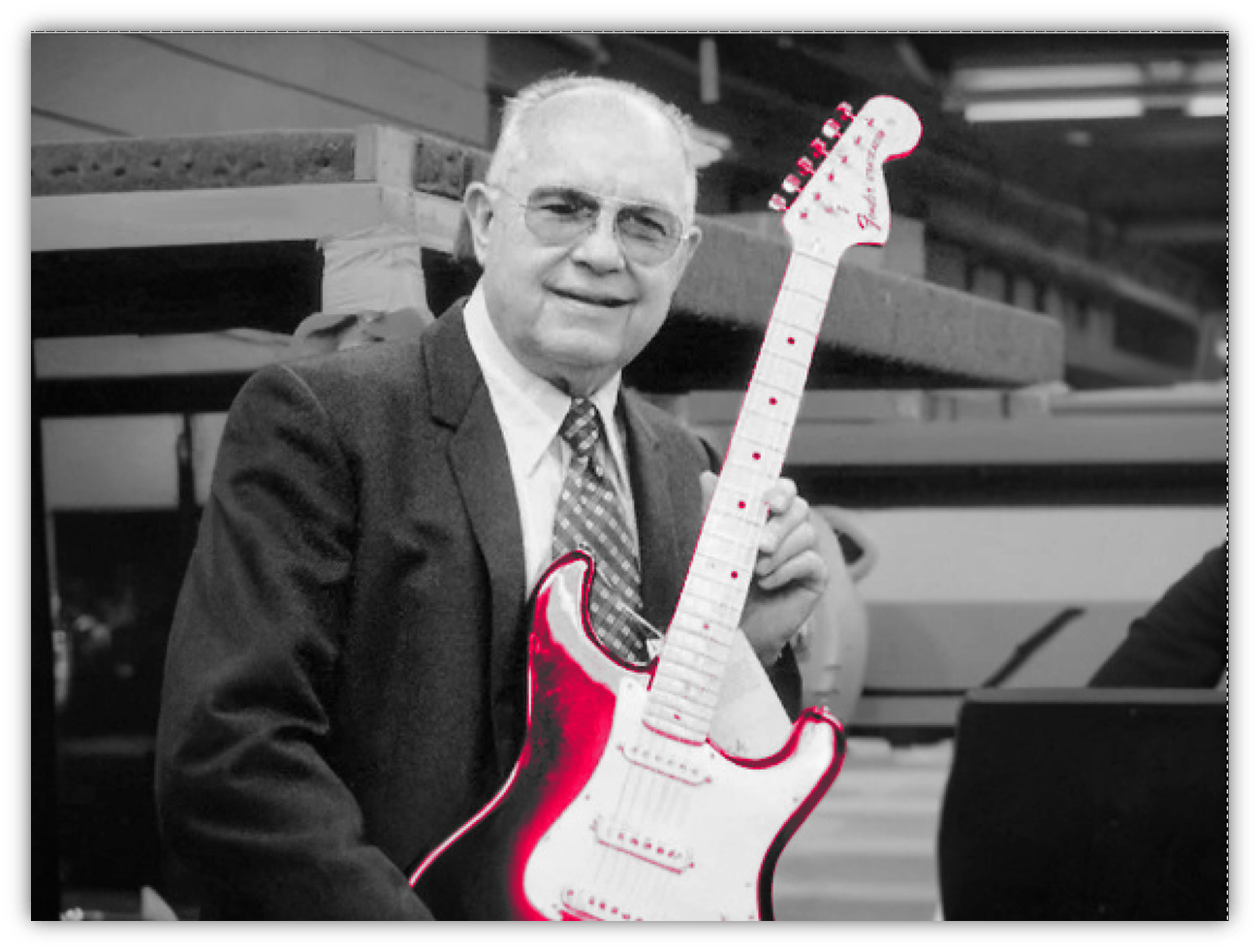

It was here that he attached a guitar neck to a pine 4×4 to build a guitar he called “The Log.”

It didn’t sustain quite as well as the rail, but it didn’t have any of the drawbacks of his attempt with the phonograph needle.

The Log isn’t the first solid body electric guitar, but it’s the one that inspired other guitar builders.

Not at first, though. In 1941, Paul showed it to the people at Epiphone, but they weren’t what you’d call ‘impressed.’ While he thought he was demonstrating the future of electric guitar design, Epiphone resisted the idea of a solid-body guitar.

He even added “wings” to make it look more like a guitar but they saw it as a gimmick. He brought it to the Gibson factory and they thought the same thing.

That same year, he worked on refining The Log in his apartment building’s basement. He wired something incorrectly, and electrocuted himself. Even geniuses make mistakes. His injuries were so bad it took him two years to recover.

During that time, he moved back to Chicago to become the music director of WJJD and WIND. When he recovered fully, in 1943, he moved to Hollywood and started a new trio.

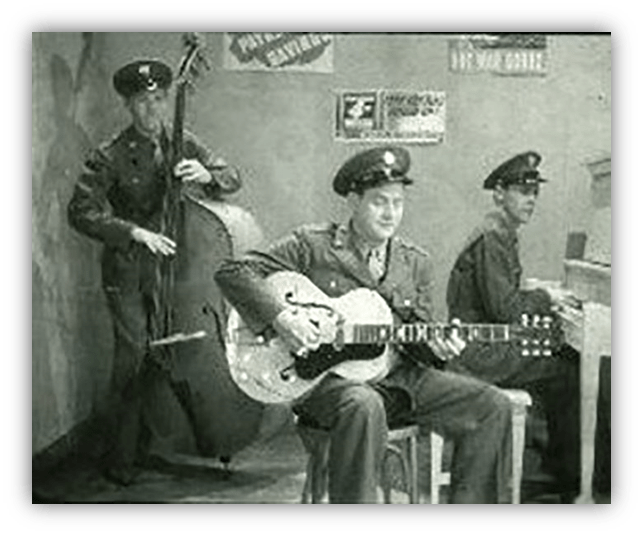

He was also drafted into the Army and was assigned to the Armed Forces Radio Network as a musician.

It was there that he met Bing Crosby, and they later recorded together as Bing Crosby With Les Paul And His Trio. Their song “It’s Been A Long, Long Time” hit #1 on Billboard’s Best-Selling Popular Retail Records chart on December 8, 1945. It replaced the same song as recorded by Harry James and His Orchestra with Kitty Kallen.

As I mentioned in my article on Crooning, Crosby was very interested in improving recording technology.

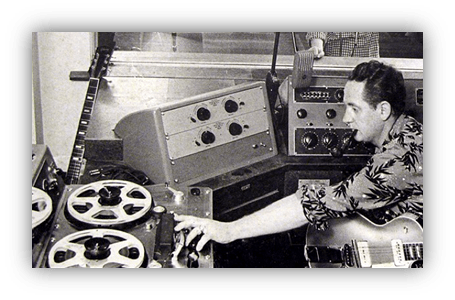

He suggested Paul build his own studio and Paul, being the curious but down-to-earth guy he was, began experimenting with recording in his garage.

When Crosby gave him an early Ampex reel-to-reel tape recorder, he tried recording his guitar at half speed.

When played back at regular speed, the guitar was twice as fast and much higher in pitch.

This same technique would later be used to make Alvin & The Chipmunks sound like chipmunks on records and cartoons.

He tried putting the microphones in different places in the room to see what sounded best. He built his own machine to cut acetate disks, using a flywheel from a Cadillac as the turntable and the belt from a dentist’s drill connected it to a small electric motor.

Acetate disks look like a regular vinyl record, but are very soft.

They can only be played a few times before wearing out, so they’re sometimes called “test pressings” because artists and producers will want to hear the record before it’s mass produced.

Acetates are usually made in mastering plants on machines that convert a reel-to-reel tape to the flat acetate disk. The acetate is then used to make a mold for the pressing plant to stamp out vinyl records. Paul was making his own – and used them for a different purpose.

He would record a single guitar track to an acetate. Then he’d re-record it onto a new acetate while playing along with it. He now had two guitars playing at the same time.

And then he did it again, and again:

Bouncing from acetate to acetate until he’d stack up multiple guitars playing different parts at the same time. He called it “sound on sound” recording.

The first record he released using this technique was an instrumental called “Lover (When You’re Near Me).” It’s a Rogers & Hart song that had already been recorded by Stan Kenton, Gene Krupa, and Harry James.

As fun and upbeat as those versions were, they were nothing like this:

Les Paul’s version of “Lover” is the first multitrack recording ever released.

Since he kept all the acetates as he went along, and they’re archived at the Les Paul Foundation, we know it has 38 tracks. On future recordings, he might bring in a drummer but he usually played everything himself.

It had been Les Paul’s goal to be unique so that his mother could tell it was him on the radio.

He succeeded.

He found the sound he had been looking for – a sound that was like no one else.

That one-of-a-kind sound became known as simply “The New Sound.” In 1950, he released an album called exactly that:

The New Sound. It was all instrumentals, including “Lover” and its B-side, “Brazil.”

“Lover” was a hit, reaching #7, and the album did well, too. They still sound fresh, but he needed one more feature to really make it big.

Les Paul wanted a singer.

And he had one in mind.

To be continued…

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb”

Persistence pays off. If at first you don’t succeed just keep trying no matter how off the wall the idea. Or off the tracks perhaps.

Given that ‘The Log’ is an elongated block of wood does that mean that the typical full bodied shape of an electric guitar is purely aesthetic or does changing the shape alter the sound in any way?

It’s not purely esthetic but that’s a big part of it. The type of wood, its density and whatnot, matters, too. The shape contributes some but mostly because it adds size and therefore stability.

I think.

Now, those pointy guitars of the 80s? Strictly looks.

I don’t know much about Les Paul beyond the basics, so most of this was new to me today. I did not know of his Chicago connection. It was cool to see the names of Chicago radio stations he worked at, 2 of which still operate under the same call letters.

He was a good Wisconsin boy so Chicago radio must’ve been a big deal for him.

Well – this was rad. Thank you!